The U.S. government is struggling to respond to another large wave of migrants fleeing poverty, violence, and corruption in the Central American region.

By Amelia Cheatham

Editorial Assistant/Special Assistant

Council on Foreign Relations

A surge of migrants from a region known as the Northern Triangle—comprised of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—has cast a spotlight on a long-suffering part of the world and pushed governments in the region and beyond to reexamine relevant policies.

Recent U.S. administrations have varied widely in the way they have framed the Northern Triangle challenge and in their responses, which have included changes to trade relations, foreign aid, and immigration enforcement. Certain actions by the Donald J. Trump administration in recent months, including separating migrant families and deploying the military to the border, have stirred significant controversy.

Who is leaving the Northern Triangle, and where are they going?

Migrants, including a growing number of women and children, are fleeing the troubled region in record numbers. On average, about 265,000 people have left annually in recent years, and this number is on track to more than double [PDF] in 2019.

Some migrants seek asylum in other parts of Latin America or in Europe. However, most endure a treacherous journey north through Mexico to the United States. Unlike past waves of migrants, in which most attempted to cross illegally without detection, migrants from the Northern Triangle often surrender to U.S. border patrol agents to claim asylum. In 2018, the United States granted asylum to roughly 13 percent [PDF] of Northern Triangle applicants, almost twice the 2015 acceptance rate [PDF]. Guatemalans currently account for the largest share of the migrant flow, followed by Hondurans and Salvadorans.

Why are so many people fleeing the region?

Many interrelated factors are driving people from the Northern Triangle, with chronic violence, corruption, and a lack of economic opportunity at the top of the list.

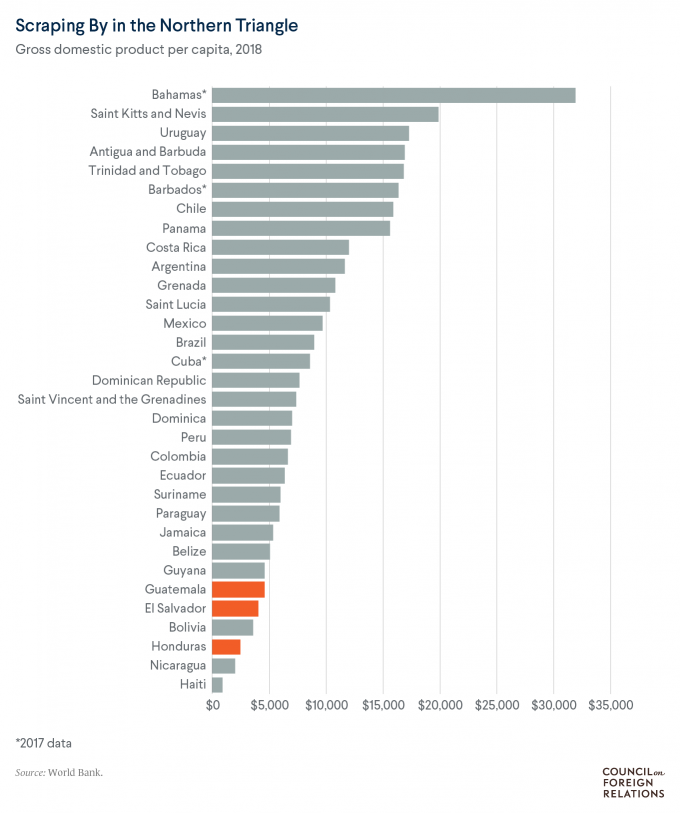

The region is among the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. In 2018, all three countries ranked in the bottom quartile for gross domestic product (GDP) per capita among Latin American states. Roughly 60 percent of Hondurans and Guatemalans live below their countries’ national poverty lines, according to the most recent data, compared to 30 percent of all Latin Americans.

Agricultural setbacks, including unpredictable weather and a destructive coffee rust, have fueled food insecurity and become a leading driver of migration. Many households depend on money sent home by relatives living and working abroad. Remittances equal a comparatively large portion—almost 18 percent [PDF]—of the three countries’ economic output. Meanwhile, corruption and meager tax revenues, particularly in Guatemala, have crippled governments’ ability to provide social services.

Many of the region’s economic problems stem from deep-rooted violence. Decades of civil war and political instability [PDF] planted the seeds for the complex criminal ecosystem that plagues the region today, which includes transnational gangs such as Mara Salvatrucha (MS-13) and the Eighteenth Street Gang (M-18). Critics say that U.S. interventions during the Cold War—including support for a coup in Guatemala, brutal government forces in El Salvador, and right-wing rebels based in Honduras known as the Contras—helped destabilize the region. Though they have declined somewhat in recent years, homicide rates in the Northern Triangle have been among the world’s highest for decades.

Women in the region are also fleeing gender-based violence, which many analysts attribute to a machismo culture. El Salvador and Honduras have Latin America’s highest rates of femicide, or murders of women and girls, according to recent UN data.

Looking ahead, experts say that population growth and climate change, which is linked to an increasing number of extreme weather events, could put further strain on Northern Triangle economies, pushing more to migrate.

How have Northern Triangle governments attempted to address these problems?

Successive governments have tried various pro-development, tough-on-crime interventions to tackle the region’s enduring problems, but they have yielded limited gains.

Economic instability. The region’s most significant coordinated effort to address economic instability is the so-called Plan of the Alliance for Prosperity (A4P), which made commitments to increase production, strengthen institutions, expand opportunities, and improve public safety. Announced after a flood of Northern Triangle migrants arrived at the U.S.-Mexico border in 2014, the $22 billion plan is 80 percent funded by El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatemala.

But while GDP has increased in Northern Triangle countries in recent years, factors including skittish foreign investors and a struggling coffee industry have stymied governments’ efforts to unlock lasting growth.

Corruption. The region has made significant progress in its battle against corruption, a longtime drag on economies. In perhaps the most prominent example, Guatemala appealed to the United Nations for assistance in establishing an independent body to investigate and prosecute criminal groups suspected of infiltrating the government. Widely trusted by Guatemalans, the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) helped convict more than three hundred officials and significantly reduce Guatemala’s homicide rate.

Meanwhile, El Salvador has charged three former presidents with money laundering or embezzlement, and recently announced plans for its own international anticorruption panel. With the support of the Organization of American States, a regional bloc, Honduras also established a corruption-fighting committee and went so far as to fire 40 percent of its police during sweeping reforms in 2016, though citizen confidence in the force remains low [PDF].

However, countries are at risk of backsliding. After CICIG began investigating President Jimmy Morales, he allowed its mandate to expire in September 2019. In Honduras, lawmakers have proposed legislation that would provide protections for corrupt officials.

Violence. Beginning in the early 2000s, Northern Triangle governments implemented a series of controversial anti-crime policies that significantly expanded police powers and enacted harsher punishments for gang members. They have also deployed military personnel to carry out police functions.

Though popular [PDF], these policies in most cases failed to reduce crime and may have indirectly led to a growth in gang membership. Mass incarcerations increased the burden on already overcrowded prisons, many of which are effectively run by gangs. There, they recruited thousands of new members and expanded their extortion rackets. The U.S. State Department, human rights groups, and journalists have raised concerns about these policies, denouncing prison conditions and police violence against civilians, including gang members.

In a change of tactic, Salvadoran officials helped broker a truce in 2012 between the MS-13 and M-18 gangs, which is credited with halving the country’s homicide rate. However, murders skyrocketed after the agreement fell apart, and the negotiations are faulted for giving the gangs political legitimacy. Candidates courted their votes during the 2014 election. In 2016, a new tough-on-crime Salvadoran government designated gangs as “terrorist groups” and arrested officials and others who helped arrange the truce.

What’s been the U.S. approach to the Northern Triangle?

Over the past twenty years, the United States has taken significant steps to try to help Northern Triangle countries manage irregular migration flows by fighting economic insecurity and violence. However, critics say U.S. policies have been largely reactive, prompted by upturns in migration to the U.S.-Mexico border.

George W. Bush administration. President Bush put trade at the top of his administration’s Central America agenda, negotiating the seven-country Dominican Republic-Central America Free Trade Agreement (CAFTA-DR), which includes El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. Under his administration, the United States also awarded Northern Triangle governments more than $650 million in development grants through the Millennium Challenge Corporation. During its second term, the administration grappled more with security challenges, including rising crime and drug trafficking in the region, and it responded with an aid package for Central America and Mexico known as the Merida Initiative.

Barack Obama administration. President Obama separated Mexico from the Merida grouping and rebranded it the Central America Regional Security Initiative (CARSI) [PDF]. Over the years, Congress has appropriated more than $2 billion in aid through CARSI to help the region’s law enforcement, counternarcotics agencies, and justice systems. Midway through his second term, Obama recast U.S. strategy [PDF] for Central America, forging what was intended to be a more holistic interagency approach to complement the region’s A4P plan.

After an upswing in migration from the region in 2014, the administration partnered with Northern Triangle governments on anti-smuggling operations and information campaigns intended to deter would-be migrants. It also cracked down on undocumented immigrants inside the United States. Court-mandated removals during his administration outpaced those under Bush, totaling about three million. After Mexico, the Northern Triangle countries accounted for the largest shares of Obama-era removals.

Donald J. Trump administration. The Trump administration has kept Obama’s framework for the region, but has prioritized stemming the flow of Central American migrants to the United States and ramping up border security.

Many of Trump’s actions have stoked controversy and sparked legal challenges. In the spring of 2018, the administration implemented a zero-tolerance policy [PDF] that sought to criminally prosecute all adults entering the United States illegally, including asylum seekers and those with children. As a result, several thousand children were separated from their parents and detained in makeshift facilities, many of which were criticized for being in poor condition. Trump officially rescinded the policy following a public backlash, though separations have continued.

In early 2019, Trump declared a national emergency at the U.S. border with Mexico, allowing him to redirect funds from the Department of Defense to construct new border barriers. He had previously deployed thousands of active-duty troops to “harden the southern border.” Additionally, the administration has attempted to restrict the flow of migrants by tightening the U.S. asylum regime and negotiating deals with Mexico and the Northern Triangle countries that would allow U.S. authorities to send many asylum seekers back to those countries.

“The administration has effectively created a situation in which the only people who can arrive at the United States’ southwest border with a claim to asylum that will be taken seriously are people from Mexico or Guatemala,” said CFR’s Paul Angelo, an expert on Latin America. “[An asylum cooperation agreement] may serve as a deterrent, but it’s not a humane policy.”

Despite a downturn in recent months, apprehensions of Northern Triangle citizens have more than doubled so far this year compared with all of 2018.

Meanwhile, Trump has slashed hundreds of millions of dollars in Northern Triangle aid, and is holding back future funding until the region “take[s] concrete actions” to address migration. The administration also tried revoking temporary protected status, a program that allows migrants from crisis-stricken countries to live and work in the United States for a period of time, for Hondurans and Salvadorans.

Originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations, 10.01.2019, under the terms a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.