Those with conservative political ideology selectively misidentify more false statements.

By Tobias Spampatti

PhD Candidate

Consumer Decision & Sustainable Behavior Lab

Renewable Energy Systems Group

University of Geneva

By Dr. Ulf J.J. Hahnel

Professor of Psychology

University of Basel

By Dr. Tobias Brosch

Professor of Psychology

Swiss Center for Affective Sciences

University of Geneva

Introduction

Competing hypotheses exist on how conservative political ideology is associated with susceptibility to misinformation. We performed a secondary analysis of responses from 1,721 participants from twelve countries in a study that investigated the effects of climate disinformation and six psychological interventions to protect participants against such disinformation. Participants were randomized to receiving twenty real climate disinformation statements or to a passive control condition. All participants then evaluated a separate set of true and false climate-related statements in support of or aiming to delay climate action in a truth discernment task. We found that conservative political ideology is selectively associated with increased misidentification of false statements aiming to delay climate action as true. These findings can be explained as a combination of expressive responding, partisanship bias, and motivated reasoning.

Implications

Despite the scientific consensus and the urgency of implementing climate change mitigation actions to limit loss of ecosystems, natural disasters, and forced migration (Pörtner et al., 2022; Romanello et al., 2023), climate objectives are not being reached (Richardson et al., 2023; Stoddard et al., 2021). Disinformation about climate science and action, spread by vested interests, is a main cause of this inertia (Hornsey & Lewandowsky, 2022; Oreskes & Conway, 2010; Pörtner et al., 2022).

Conservative political ideology is a prominent risk factor for susceptibility to misinformation and to skepticism about climate science (Ecker et al., 2022; Hornsey et al., 2018; van Bavel et al., 2021). Non-experimental evidence shows that people who endorse a conservative ideology are more frequently exposed to false information about climate change (Falkenberg et al., 2022), are more skeptical of climate change (Hornsey et al., 2018), and share misinformation more often (Guess et al., 2019; Nikolov et al., 2019). Conservatives may furthermore be resistant to behavioral interventions against misinformation (Pretus et al., 2023; Rathje et al., 2022).

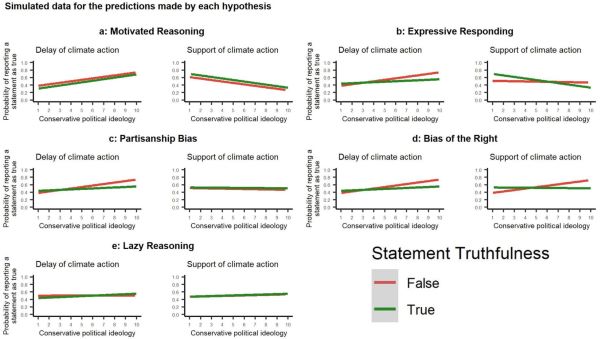

Different hypotheses have been proposed to describe the mechanisms behind conservatives’ misinformation susceptibility (Borukhson et al., 2022). Overall, these hypotheses refer to two dimensions of information that can affect the ability to discriminate between true and false information (i.e., truth discernment): 1) being true or false, and 2) being congruent or incongruent with a person’s political ideology. Crucially, each hypothesis leads to different predictions of how political ideology may influence truth discernment (see Figure 1 in Appendix B):

a) Motivated reasoning hypothesis: People preferentially process information congruent with their own political ideology (Druckman & McGrath, 2019; Kunda, 1990). This suggests that conservatives (liberals) are more likely to rate statements congruent with their conservative (liberal) ideology as true and are more likely to rate statements incongruent with their ideology as false. In this perspective, climate misinformation “fits” conservatives’ pre-existing belief network better (Hornsey et al., 2018; Jylhä & Akrami, 2015), and thus climate misinformation enjoys less epistemic scrutiny during information processing.

b) Expressive responding hypothesis: People agree with information that reflects the positions expressed in their political environment (Jerit & Zhao, 2020; Ross & Levy, 2023). This suggests that conservatives (liberals) are more likely to rate false (true) statements congruent with their ideology as true because such statements are more present in their information ecosystem (Falkenberg et al., 2022).

c) Partisanship bias hypothesis: Whereas expressive responding predicts that people will agree with any political position prevalent in their political environment, the partisanship bias hypothesis propounds that people interpret information in a biased manner if it is aligned with a cherished ideological worldview or has been internalized into the identity of the political ingroup. As climate skepticism became internalized in conservative political ideology and identity (Doell et al., 2021), conservatives may be more likely to agree with climate misinformation as it now reflects their ideology and political identity (van Bavel et al., 2021). The partisanship bias thus suggests that conservatives are more likely to rate false statements congruent with their ideology as true than liberals.

d) Bias of the right hypothesis: People who endorse a conservative ideology might be more susceptible to misinformation (Baron & Jost, 2019). This could be due to conservatives’ political views more strongly affecting truth discernment (Jost et al., 2018) while being less aware of this influence (Geers et al., 2024). This suggests that conservatives are more likely to rate (both ideologically congruent and ideologically incongruent) false statements as true than liberals.

e) Lazy reasoning hypothesis: Misinformation susceptibility is primarily driven by lack of careful reasoning when encountering information (Pennycook & Rand, 2019). This suggests that conservatives and liberals are equally likely to rate both ideologically congruent and ideologically incongruent statements as true.

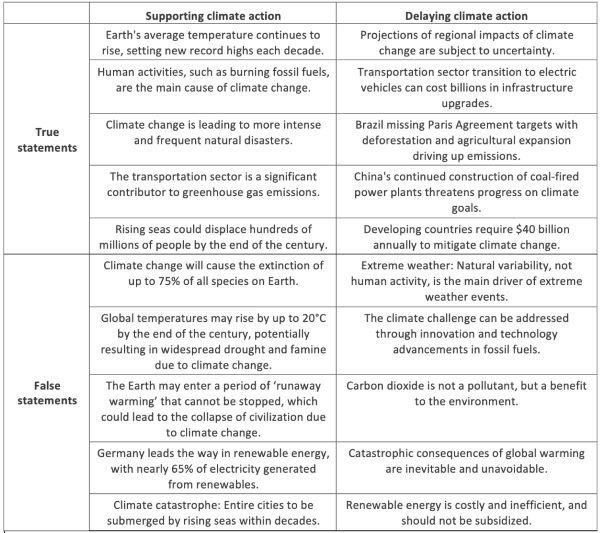

To understand how political ideology influences truth discernment of climate information and misinformation, we conducted a secondary analysis of a cross-cultural study on susceptibility to climate misinformation (Spampatti, Hahnel et al., 2023). In the original study, 1,721 participants from the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Australia, New Zealand, Singapore, Philippines, India, Pakistan, Nigeria, and South Africa had to discern whether twenty statements about climate change were true or false (climate truth discernment task; see Methods). The statements were distributed on two dimensions: 1) true and false statements about climate change and climate mitigation action (see Table 1), and 2) statements congruent with conservative ideology—i.e., delaying climate action (Lamb et al., 2020)—and statements incongruent with a conservative ideology—i.e., supporting climate action (Berkebile-Weinberg, Goldwert, et al., 2024; Hornsey et al., 2018). We measured how each dimension (true/false, ideologically congruent/incongruent, and their interaction) interacts with political ideology when people discern the veracity of climate statements and compared the results to the predictions of the different hypotheses.

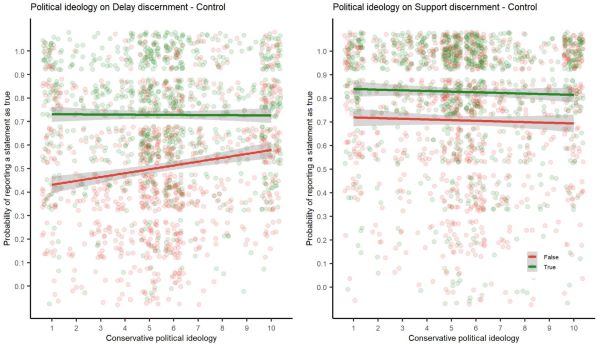

Conservatives were worse at recognizing false statements aiming to delay climate action as false (see Figure 2). The more conservative the participants, the more likely they were to evaluate these false, but ideologically congruent, statements to be true. The effect of political ideology did not extend to evaluating true statements supporting climate action as false more often. Among the simulations, these findings best overlapped with the visualization of the partisanship bias hypothesis (see Figure 1c and Figure 2): More conservative participants were more closely aligned to false, ideologically congruent statements about climate change. The categorization of true, ideologically incongruent statements was not impeded and was quite high, as in previous findings (Pennycook et al., 2023). Alternatively, the data depicted in Figure 2 also matched the expressive responding simulation (see Figure 1b). Congruent with this hypothesis, conservative participants who received no disinformation (i.e., passive control condition) may have recognized both the false information aiming to delay climate action and the true information in support of climate action as true because they are both present in their information environment (Effrosynidis et al., 2022; Falkenberg et al., 2022; Flamino et al., 2023; Lamb et al., 2020). The findings do not suggest that conservatives are more susceptible to disinformation (Baron & Jost, 2019), nor that people engage in motivated reasoning (Kunda, 1990), as evidenced by the largely non-overlapping slopes of the simulations (see Figure 1a–d) and the actual data (see Figure 2).

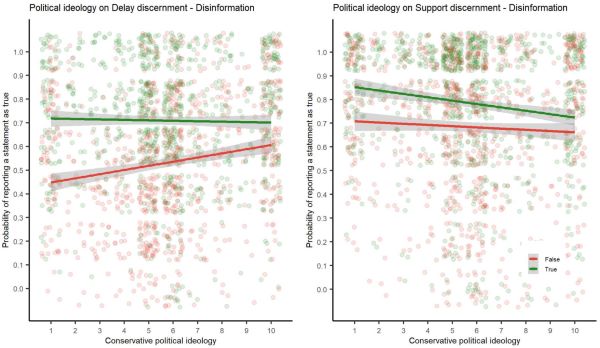

After reading twenty climate disinformation statements before completing the truth discernment task, conservative participants became more likely to also report true statements supporting climate action as false (see Figure 3). This evidence was suggestive, as the p-value was between 0.05 and 0.005 (Benjamin et al., 2018). In other words, processing disinformation stimulated conservative participants to engage in reasoning and accept false statements delaying climate action while rejecting true statements supporting climate action. This reasoning was not fully motivated: If it were, truth ratings about ideologically congruent false statements arguing for delay (i.e., ideologically congruent) should have been increasingly impaired (Kunda, 1990).

Overall, the findings suggest that conservatives can accurately recognize and categorize true information supporting climate action but inaccurately categorize ideologically congruent but false statements. Their truth ratings of true information supporting climate action is only impaired if they are exposed to climate disinformation. Comparing these findings with the literature-derived hypotheses (i.e., visually comparing the slopes from Figure 1 with the slopes from Figures 2 and 3) showcases how truth discernment of climate statements is best explained by a mix of expressive responding (see Figure 1b), motivated reasoning (see Figure 1a), and partisanship bias (see Figure 1c).

Both findings also have practical implications. Although recent work calls to boost true information (e.g., Acerbi et al., 2022), our results suggest that this strategy may suffer from a ceiling effect in the climate domain because people across the ideological spectrum recognize true information supporting climate action. Instead, conservatives misidentify misinformation delaying climate action as true more and their recognition of true information supporting climate action is more affected by disinformation. Redirecting conservatives from their information environment where false information delaying climate action is more prevalent (Falkenberg et al., 2022) towards accurate climate communicators may reduce exposure to and belief in this type of misinformation (van Bavel et al., 2021). Fighting disinformation also remains important but requires the development of better interventions, tested against validated stimuli (Spampatti, Brosch et al., 2023) and tailored to conservative audiences (Pretus et al., 2023).

Findings

Finding 1: Conservatives are selectively susceptible to false statements arguing for the delay of climate action.

We analyzed data from the passive control condition with a multilevel model, with the sum of statements categorized as true as the dependent variable (following Maertens et al., 2023; see Table 1 in Appendix B) predicted by political ideology, true and false statements (factor), statements supporting or delaying climate action (factor), and their interactions. The model also contained a random intercept per participant, a random intercept per country, and age and gender as covariates. The results were replicated using signal detection theory (see Appendix D).

Crucially, the three-way interaction between political ideology and the two dimensions of climate statements was significant, F(1, 2604) = 9.1016, p < .001. Simple slopes within the four types of climate statements show that the more conservative participants were, the more frequently they evaluated false statements delaying climate action as being true, F-ratio = 20.176, p < .001 (see Figure 2). Political ideology did not influence evaluating true statements delaying climate action (F-ratio = 0.400, p = .53), false statements supporting climate action (F-ratio = 1.739, p = .19), nor true statements supporting climate action (F-ratio = 1.664, p = .20). Equivalence tests (Lakens, 2017) confirmed that the associations between political ideology and truth ratings of true statements supporting climate action, z(868) = 2.0684, p = .02, r = -0.03, 90% CI[-0.09, 0.03], and delaying climate action, z(868) = 2.7686, p = .003, r = -0.006, 90% CI[-0.06, 0.05]; and false of statements supporting climate action, z(868) = 2.1773, p = .015, r = -0.03, 90% CI[-0.08, 0.03], were small enough to be practically meaningless (significantly smaller than r = 0.1).

Finding 2: Climate disinformation only hampers conservatives’ ability to accurately evaluate true statements supporting climate action.

We analyzed data from the disinformation condition with the same multilevel model as the passive control condition (see Table B2 in Appendix B).1 The three-way interaction between political ideology and the dimensions of climate information was not significant, F(1, 2559) = 9.1016, p = .08. Upon visual inspection of the data and because three-way interactions are frequently underpowered (Baranger et al., 2023), we directly tested the association between political ideology and true statements supporting climate action. This revealed a significant negative correlation, z(853) = -4.1087, p <. 001, r = -0.14, 95% CI[-0.21, -0.07]: more conservative participants were more likely to evaluate true statements supporting climate action as false. The association between political ideology and false statements delaying climate action was also significant, z(853) = 4.9128, p < .001, r = 0.17, 95% CI[0.10, 0.23], and an equivalence test suggested that this association was practically the same between the two experimental conditions (z = 0.0908, Δr = -0.01, p = .03). Equivalence tests confirmed that the association between political ideology and number of true statements about climate delay rated as true, z(853) = 2.3461, p = .009, r= -0.02, 90% CI[-0.08, 0.04], and false statements supporting climate action rated as true, z(868) = 1.6271, p = .052, r = -0.04, 90% CI[-0.10, 0.01], was small enough to be practically meaningless in the disinformation condition.

Methods

The experimental methods are described in full in Spampatti, Hahnel et al. (2023; open materials are available at https://osf.io/m58zx). After consenting, participants reported their demographics (gender, age, education), completed an individual differences measure (Cognitive Reflection Task Version 2; Thomson & Oppenheimer, 2016), and responded to their political ideology in a single item with a 10-point scale presented in a random order. The single item stated: “Conservative/Right and Liberal/Left are terms that are frequently used to describe somebody’s political ideology. Please indicate in the following scale how you would place yourself in terms of your political ideology. 10-point scale: 1 = Extreme liberalism/left to 10 = Extreme conservativism/right.” A “two-strikes-you’re out” attention check (“Please select ‘3’ to make sure you are paying attention”) first triggered a warning and a time penalty, then was presented a second time to screen out inattentive participants (n = 10). The remaining participants were randomly allocated to one of eight conditions, two of which are of current interest: the passive control condition and the disinformation condition. In the disinformation condition, participants received twenty real climate disinformation statements (in randomized order, as a screenshot of an anonymous post with a 2s time lock), taken from a validated set of climate disinformation statements (Spampatti, Brosch, et al., 2023; see Table A2 in Appendix A).

Participants then responded to the climate change perceptions scale (van Valkengoed et al., 2021) and completed the Work for Environmental Protection Task (Lange & Dewitte, 2021), two dependent variables not of interest for this article, and the climate-related truth discernment task, inspired by a domain-general truth discernment task (Maertens et al., 2023). Participants categorized 20 climate-related statements as false or real (“Please categorize the following statements as either ‘False Statement’ or ‘Real Statement’”; binary choice: [Real]; [False], item and response order randomized). All statements of the truth discernment task were generated with an AI tool (ChatGPT, Version 4), fact checked, and unanimously selected by the authors. The statements were equally divided between true and false headlines and between supporting or delaying climate science and action (see Table 1). The survey duration was 28 minutes.

See references at source.

Originally published by Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review, 10.17.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.