The relationship between power—or politics—and culture in French history is an ambivalent one, defined as much by conflict and censorship as by cooperation and patronage.

Introduction

Throughout French history the powerful have sought to harness culture to their own ends. They understood that the representation of power—what today we call “image”—is a form of power itself. They patronized artists, artisans, and intellectuals who produced works that proclaimed the legitimacy of their rule, reinforced their authority, and enhanced their prestige. At times, they stifled creative impulses incompatible with their ambition. The relationship between power—or politics—and culture in French history is thus an ambivalent one, defined as much by conflict and censorship as by cooperation and patronage.

This traces the history of this relationship from Charlemagne (b. 742?–d. 814) to Charles de Gaulle (b. 1890–d. 1970), through the prism of more than 200 magnificent “treasures” on loan from the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris. The Bibliothèque’s generous collaboration has made possible a unique exhibition which includes many items never before seen outside of France. The choice of items was dictated as much by their historical importance as by their artistic value in the hope that they will provide insight into, and spark curiosity about, the complex history of the United States’ oldest ally.

Monarchs and Monasteries: Knowledge and Power in Medieval France, Late 8th to Late 15th Centuries

By the mid-eighth century when the Carolingian family deposed the Merovingian dynasty, the king was more than a warlord, he was also a religious figure, the Christian leader of his subjects, the new chosen people. From the start, his dual role spawned a potent mix of religion, politics, and culture.

Carolingian kings actively supported the study of religious texts which prepared monks, the “soldiers of Christ,” to lead their people to salvation. Their courts served as important centers for book collection, book production, and the dissemination of antique culture throughout the West. However, it was abbeys and monasteries that played the leading cultural role in the Carolingian kingdoms for it was in their scriptoria that manuscripts were produced and studied. Among the most famous were those at Saint-Denis, Corbie, and Cluny.

The monastery of Saint-Denis’ wealth and connections with Italy made it one of the wellsprings of the Carolingian renaissance. It also became the royal abbey and royal mausoleum, guarding the regalia and the oriflamme, a crimson banner which accompanied the kings to battle. Monks at the monastery of Corbie not only collected and copied books but made their own contributions to the literature of theology, biography, and polemic. In the eighth century, Corbie’s scribes helped perfect the clear script type known as the Carolingian minuscule. The abbey of Cluny played a critical role in the monastic reform movement begun in the tenth century, forming the hub of a network of European monasteries where prayer, viewed as the remedy for sinfulness, took on ever increasing importance.

During the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, French power, culture and authority began to pass from rural monastic centers to cities and the royal court. Paris became the artistic and commercial hub of the kingdom, as well as its administrative and judicial center. From the mid-thirteenth century through the sixteenth century, the “religion of royalty” summarized by the motto “one king, one faith” (un roi, une foi) reigned supreme in France. Royal religion was disseminated through ceremonies and symbols preserved in manuscripts and in the artifacts the kings commissioned.

Each royal ceremony was carefully staged and orchestrated to impress those who witnessed it. The central ritual of the monarchy was the installation ceremony at Rheims during which the king was anointed with holy oil believed to endow him with the ability to heal a variety of diseases. Other occasions, like royal marriages and ceremonies marking the king’s entry into a city, reinforced his authority which was symbolized by his regalia: the ring, the spurs, the sword, the crown, the scepter, and the hand of justice.

Early on, French kings understood that they could derive great power and prestige from the written word, particularly when it was embellished by magnificent illuminations. The potent impact of these images, symbols, and texts on the people of France is evidenced by the fury with which opponents of the monarchy and Catholicism—the Huguenots in the sixteenth century, the Revolutionaries in the eighteenth—sought to destroy them, as if they believed they could eradicate the power of church and monarch by eliminating the material traces and representations of their authority.

Lectionaries, which contained lections (readings from Scripture) to be read at church services, figure among the most beautifully decorated manuscripts of the early Middle Ages. Considered the image of the Divine Word, these manuscripts were carried in church processions to the altar and then to the pulpit, where the deacon conducted the reading. Gold, silver, and purple symbolized the celestial kingdom, the reward of eternal life, and the radiating splendor of God’s Word.

This is a plastic replica of the bronze armchair which belonged to the abbey of Saint-Denis near Paris, and which was imaginatively attributed in the Middle Ages to the Merovingian king, Dagobert I (623/9–639). In the Middle Ages religious institutions maintained magnificent collections of relics such as this throne. Such treasures provided a concrete expression of the power of the Church and of the Monarchy, and could be melted down or pawned for cash.

The style of the rich ornamentation of this manuscript suggests that it was prepared at the flourishing scriptorium of Saint-Amand-en-Pévèle at the request of Charles the Bald (843–877) for his favorite abbey, Saint-Denis. As was customary for Carolingian sacramentaries, only the Preface and the Canon of the Mass are illustrated, in this case in the very beautiful, purely ornamental style that marked the end of Carolingian illumination.

The Gradual was a basic book of the liturgy that originally contained the chants of the Proper of the Mass. Remarkably decorative, embellished with marvelously colored geometric designs and interlacing, this manuscript exhibits a style that prevailed between 1050 and 1150 in France, from Limoges to the Pyrenees and into Spain. Crucial to the history of music, this Gradual contains elements of the Gallican chant used in Gaul before the Gregorian reform of the eleventh century.

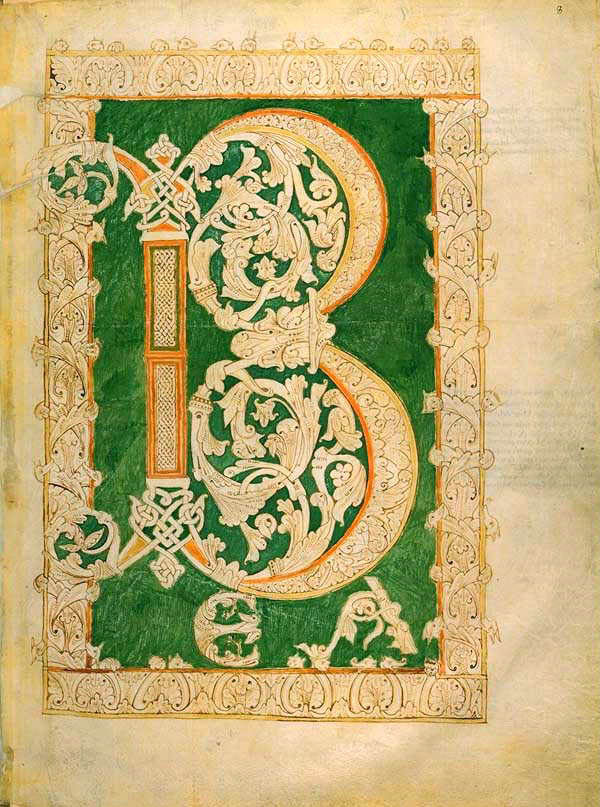

Founded by Clovis’s son Childebert (511–558) in the sixth century, the Parisian abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés was an influential intellectual center up to the eighteenth century. The abbey’s prosperity dates from the eleventh century when it housed a flourishing scriptorium. This Psalter-hymnal, with its decorative alphabet and sparing use of highlights, is a brilliant example of Romanesque art from the Ile-de-France.

The fifteen miniatures of the Coronation Ordinal of 1250 present the oldest known iconographic cycle showing the coronation of a French king in the cathedral of Rheims, virtually as it would be staged until 1825. The archbishop of Rheims, assisted by the abbots of Saint-Remi of Rheims and of Saint-Denis, officiated in the presence of the peers of the realm. This manuscript was consulted for the coronations of Francis I (1515) and Henry IV (1594).

Copied around 1250–54, this Bible is probably the oldest and most beautiful illuminated manuscript to come out of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem which was founded in the aftermath of the first crusade (1096–1099). Saint Louis probably commissioned this richly-decorated Bible on one of his visits to Acre, a flourishing port on the Palestine coast, and, after the loss of Jerusalem in 1187, the de facto capital of the Latin Kingdom and the Patriarchal See.

The Picture of the World apparently is the oldest encyclopedic treatise written in a vernacular language. Composed in the dialect of Lorraine, it was written in 1246 for Saint Louis’s brother, Robert d’Artois (b. 1216–d. 1250), who wanted to know how the world had been “constructed.” The text is divided into three parts: God and human intelligence; nature and the elements of the cosmos; and, physical phenomena and astronomy. This opening depicts the arts of Logic, Rhetoric, and Arithmetic.

In 1279–80, at the request of King Philip the Bold (1270–1285), Friar Laurent, the king’s confessor, composed a manual of moral instruction known as La Somme le roi. The author was inspired by earlier texts, in particular a treatise on vices and virtues entitled the Miroir du Monde (Mirror of the World). La Somme le roi was translated into numerous languages and dialects and achieved a wide circulation.

This account is the French translation of a Latin original, since lost, which was used in the canonization proceedings of Louis IX (1226–1270). It was composed for Blanche of France, Saint Louis’s daughter. The manuscript’s ninety illustrations are divided into two series: the first relates to the edifying actions of the king’s life; the second consists of sixty-five supplementary miniatures illustrating the miracles that occurred at the sovereign’s tomb in the Abbey of Saint-Denis.

A poet and innovative composer, Guillaume de Machaut was a major figure in fourteenth-century French literature and music. Apart from his celebrated Coronation Mass, his art was essentially of secular inspiration and found its most finished expression in a series of Dits (stories in verse, interspersed with lyric and musical pieces). In them the author celebrated the traditional themes of courtly love. This manuscript may well have been intended for the royal family.

In 1372, Charles V (1364–1380) had Foulechat translate Policraticus, an important medieval text about political theory which projected a theocratic vision of the State and posed the question of monarchical legitimacy and tyrannicide. This illustration depicts the wise king Charles V seated on a chair from which justice was meted out and pointing to the manuscript placed on a bookwheel. He is the very picture of the learned and just king blessed by the hand of God.

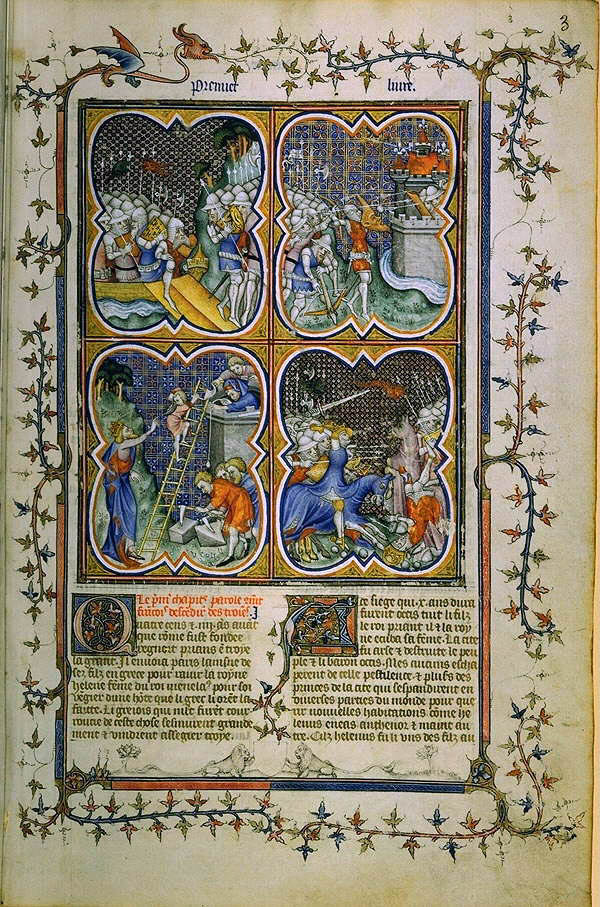

The manuscript on display contains the French-language version of the royal chronicles up to the death of Philip VI of Valois in 1350, as they were composed at the abbey of Saint-Denis. This volume was probably produced around 1370 for Charles V. The four miniatures that make up the painting at the beginning of the manuscript illustrate the key features of the myth of the Trojan origins of the Franks.

ean de France, Duke of Berry (b. 1340–d. 1416), is associated with some of the most beautiful illuminated manuscripts from the end of the Middle Ages. The text of his celebrated Psalter is preceded by twenty-four paintings in grisaille which constitute one of the most remarkable interpretations of the Apostle’s Creed, an extremely popular iconographic theme of the period. The figures and their strongly individualized physiognomies are the work of the sculptor André Beauneveu.

Christine de Pisan, the first female writer to earn a living from her pen, defended the status of women. In this illustration, aided by Reason, Uprightness, and Justice, she lays the foundation of a City exclusively for women who have served the cause of women (female warriors, politicians, good wives, lovers, and inventors, among others). The imagined City will be crowned by the glory of the Virgin and sainted women.

This manuscript belonged to the Duke of Burgundy, Philip the Bold (b. 1342–d. 1404), and reflects the interest of the dukes of Burgundy in Oriental matters. The text describes the victory in 1402 at Ankara of Tamerlane, khan of Mongolia, which temporarily ended the Ottoman threat to Constantinople. The manuscript’s illumination reflects the Flemish influence that revitalized Parisian painting at the beginning of the fifteenth century. This folio depicts the coronation of Genghis Khan (b. 1162-d. 1227).

The Path to Royal Absolutism: The Renaissance and Early 17th Century

The political and cultural history of France from 1498 to 1661, that is, from Louis XII’s accession to the throne to Louis XIV’s personal assumption of power, can be divided into three major phases. The first, up to the death of Henry II in 1559, looked to Italy as a land ripe for conquest and as an inspiration for France’s own Renaissance.

The second period (1562–1598) saw the realm convulsed by eight civil wars—the Wars of Religion—as France grappled with the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation was both a theological dispute about the proper understanding and practice of Christianity and a political controversy about the legal status of the new Reformation churches. In France, the conflict took on a further political dimension when members of the high nobility attempted to take advantage of the chaos to wrest power from the king. Factions tore each other apart. The weakened monarchy had to reconquer Paris (1594) and drive the Spanish from the kingdom (1597). Henry IV finally reestablished the monarchy’s legitimacy when he legally recognized French Protestants and gave them freedom of worship.

Henry IV’s conversion to Catholicism in 1594 inaugurated a new era and a new dynasty of French kings, the Bourbons. Through a governance as militaristic and absolutist as that of any of his predecessors, Henry censored writers and preachers in the name of public peace. Ironically, he would be assassinated in 1610 (after nineteen unsuccessful attempts on his life), falling victim to the very violence and religious passions he sought to quell.

During the half-century that followed, Cardinal Richelieu (b. 1585–d. 1642) orchestrated the royal government’s reconquest of domestic control. The monarchy reinforced its monitoring of printing, totally strangling the emerging press. The French language itself became an object of government concern through the newly created Académie Française, a fitting example of Richelieu’s overall program of state control over politics and culture. Once the last rebellion of the feudal nobility was suppressed, the framework and mechanisms of absolute monarchy were in place, needing only the arrival of Louis XIV to complete the scene.

In this illustration, the combined arms of Brittany and Orléans appearing behind the lady praying to the Virgin indicate that this book was produced for Marguerite d’Orléans, sister of Charles d’Orléans. One of the most exquisite examples of fifteenth-century French illumination, this book of hours was executed in a complex series of stages, its decoration inspired by diverse sources and artists. The artist’s decorative genius is affirmed most strongly in the imaginative borders.

Commissioned by King John the Good (1350–1364), this first major literal translation of Livy into French was a key medieval reference work on antiquity. It inaugurated the translations commissioned under Charles V (1364–1380) and Charles VI (1380–1422), which provided aristocratic circles with a cultural model established by the royal entourage. The opening illustration shows Livy in his study. Carthage is depicted as the Ile de la Cité in Paris while Hannibal asks his father to take him to Spain.

This book outlines the procedures for settling a quarrel through trial by combat. This opening depicts the confrontation which takes place in an enclosed space, before juges d’armes who monitor the legality of the blows exchanged, and an elegant audience of lords and ladies. This copy was made for François II, Duke of Brittany (1458–1488). Its diminutive format, presentation of miniatures, and lavish decoration link the manuscript to books of hours rather than to treatises.

In an effort to guarantee the allegiance of ranking nobles, Louis XI (1461–1483) founded the Order of Saint Michael in 1469. The book of Statutes exhibited here—the king’s own copy and the finest of all extant copies—was illuminated by Jean Fouquet (b. around 1420–d. around 1480), the king’s official painter. The manuscript’s only large miniature depicts the king surrounded by the order’s fifteen knights with the four officers of the Order in the background.

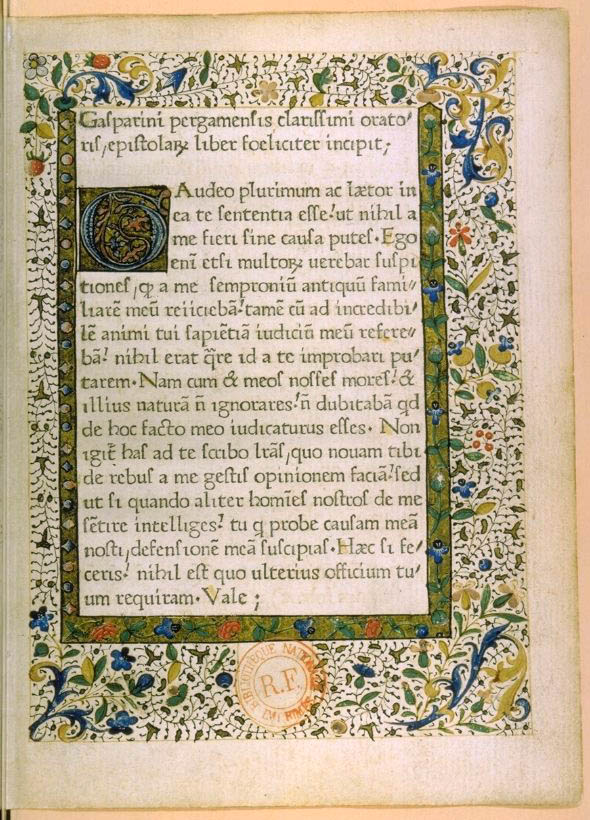

Gasparino Barzizza, one of the first Italian Humanists, taught rhetoric, grammar, and moral philosophy, hoping to revive Latin literature. The examples of epistolary art in his Epistolae were designed to teach prose composition. The edition displayed here is the first book printed in France. The first French press was set up at the Sorbonne by two professors who recruited three printers from Germany to whom Louis XI (1461–1483) granted letters of naturalization in 1475.

At the close of the fourteenth century, Jean, Duke of Berry and Count of Poitou (b. 1340-d. 1416), commissioned a genealogical romance glorifying the Lusignan family from Poitou. Jean d’Arras, the author, drew upon elements of oral, folk literature—a mother-goddess and the breaking of a taboo—creating a new type of romance, different from contemporary tales of Charlemagne and King Arthur. This illustration shows the husband breaking the taboo by viewing his wife bathing.

This selection of coins depicts French coinage between the late eighth century and early sixteenth century. Charlemagne’s reform of 794 created a new denarius whose appearance would change little until the tenth century. The denarius of Charles the Bald (840–877), a half-century later, still closely resembles that of Charlemagne (768–814). Exceptions to the almost exclusive use of silver that lasted until about 1270 included the gold solidi of Louis the Pious (814–840), intended for commerce with the peoples of the north. The absence of a purely royal coinage under Hugh Capet (987–996) suggests the weakness of the new Capetian dynasty: only some denarii and oboles issued by the bishop of Beauvais and a unique denarius of Laon survive. Philip II (1180–1223) instituted the double system of the denier parisis north of the Loire and the denier tournois to the south. Under Louis IX (1226–1270) appeared the first multiple of the denier, the gros denier worth twelve denarii. The period from Philip IV (1285–1314) to Philip VI (1328–1350) saw a multitude of gold coins of varied and artistic types, including the gold florin “à la Reine”. The royal d’or, ordered October 9, 1429 represents Charles VII (1422–1461) shortly after his coronation. Although already part of the kingdom of France, Brittany retained some issues of a special type until the mid-sixteenth century. The king’s portrait appeared for the first time under Louis XII (1498–1515) on heavy silver coins, called “testons”, opening a new chapter in the history of French coins.

This manuscript’s script and style of illumination confirm that it was produced in the northwestern city of Rouen. Its illustrations represent the first serious attempt by a French artist to illustrate Petrarch’s poem. The artist depicted, in a series of diptychs, the triumphs of Love, of Chastity, of Reason, of Death, of Fame (portrayed here), of Time, and of the Trinity.

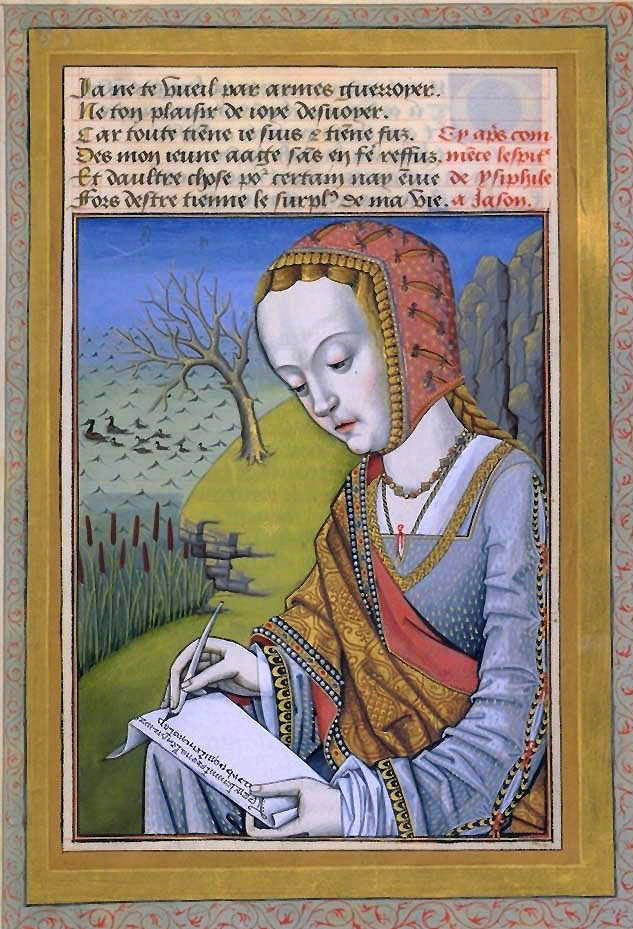

Louise of Savoy (b. 1467–d. 1531), widow of Charles d’Angoulême (b. 1460–d. 1496) and mother of Francis I (1515–1547), commissioned this translation of Ovid’s Epistulae heroidum, a collection of letters fictitiously attributed to heroines of Antiquity grieving over their unrequited loves. The illustrations represent the heroines, whose faces give the appearance of being authentic portraits, in the act of writing. Dress is alternately exotic or inspired by the fashion of the day. Depicted here is Hypsipylé, first wife of Jason.

Louis XII’s rapid conquest of the city of Genoa in April 1507 struck public opinion as a remarkable feat of arms, sparking rapturous accounts by court chroniclers and poets who extolled the king’s greatness and fame. Jean Marot, the king’s official poet, composed a verse account of the victorious expedition, copied in a fine manuscript intended for Louis’s wife, Anne of Brittany (b. 1477–d. 1514). In this illustration Louis XII makes a triumphal entry into Genoa.

This little book of hours may have been produced for Queen Anne of Brittany. This is not certain as so little account was taken of the saints for whom she felt particular devotion and who were to be found in her prayerbook and in the Great Book of Hours. The only saint to be honored with a miniature in the section of intercessory prayers is Saint Louis. Shown here is an illustration of the Annunciation.

In this painting, the king, Francis I (1515–1547), wears Minerva’s helmet, Mars’s armor, Mercury’s winged sandals and his staff, Diana’s hunting horn, and Cupid’s bow and quiver; and a Medusa’s head adorns his breastplate. This elevation of the monarch into a superman with the attributes of the Olympic gods was typical of royal iconography in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.

As proof of the budding alliance between the French monarchy and the Ottoman sultans in the early sixteenth century, this letter was addressed by Suleyman (Suleiman) the Magnificent (1520–1566) to Francis I in 1536. Infused with the appropriate solemnity and magnificence, it was calligraphed with great care in a number of scripts, using inks of different colors. This important document marks the beginning of a permanent French embassy at the Ottoman court.

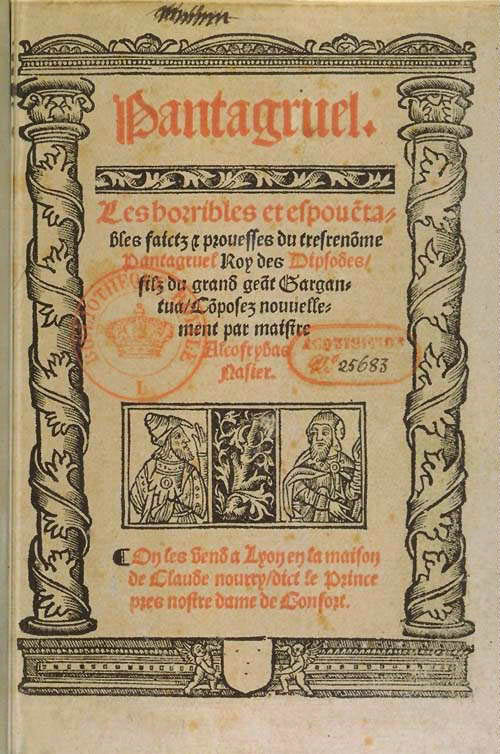

The title character of Pantagruel, of which this is the oldest extant version, can be traced to a figure in fifteenth-century mystery plays: the sprite of thirst, who incited people to drink by throwing them salt. The book celebrates wine, love, and mortal pleasures. All the coarse passages in this copy were inked out in the sixteenth century.

Although a Catholic, Queen Marguerite of Navarre (b. 1492–d. 1549), King Francis I’s sister, protected and corresponded with reformers. Written for Marguerite at the time of her marriage (1527), this manuscript opens with two large miniatures. On folio 1 verso is a golden crown inside a wreath bearing the arms of the princess. On folio 2, Marguerite’s husband, Henry of Albret, king of Navarre (1517–1555) and grandfather of the future Henry IV (1589–1610), is shown holding a marguerite daisy.

Oronce Fine was one of the rare French geographers in the Renaissance to prepare maps of the world. This map is bordered with a handsome Renaissance decoration: two columns support a pediment bearing a Latin inscription signifying “A new and complete description of the world,” interrupted in the middle by a coat of arms of France. Also to be noted is a vast southern land mass (Terra Australis), recently discovered but not yet explored.

Traditional in text and layout, this finely-crafted prayer book meant for private devotion and enjoyment, is innovative in its Old Testament miniatures, which illustrate the cares and duties of kingship. The last miniature, exhibited here, shows Henry II (1547–1569) healing the diseased with his touch. The newly-crowned king is garbed in his gold, fleur-de-lis-embroidered regalia; on the far right stands the Archbishop of Rheims, who presided at Henry’s coronation.

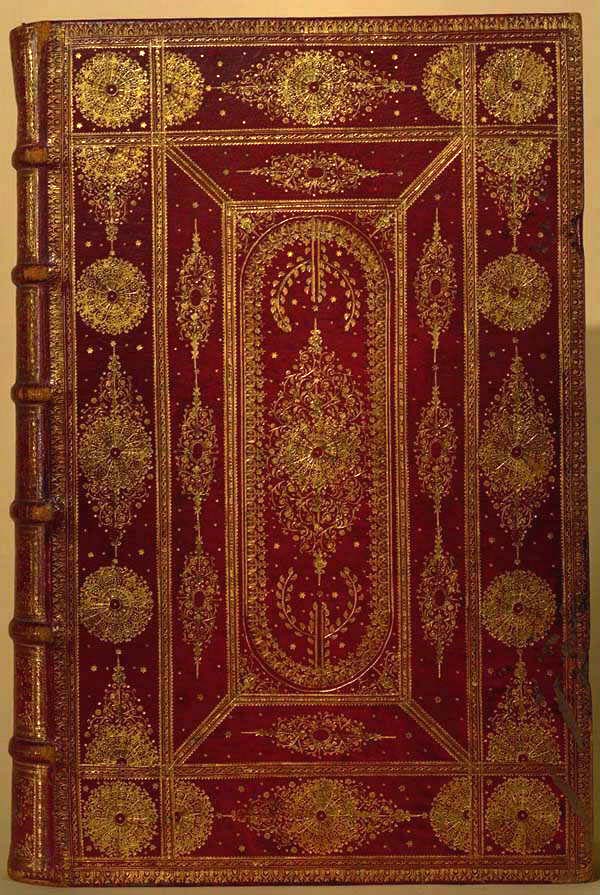

This binding by Claude Picques, binder to Francis I, Henry II, and Francis II, is one of the most beautiful sixteenth-century French bindings. On a ground of black morocco, the boards present interlacing, ornamental foliage of light tan morocco, with certain geometric and foliate patterns painted in green. The binding bears the arms and monograms of Henry II and Catherine de Medici (b. 1519–d. 1589), but also the “D” of Diane de Poitiers (b. 1499–d. 1566), the king’s paramour.

This portrait in black chalk is one of the finest achievements of François Clouet (b. before 1522–d. 1572) from the last years of his career. Queen Catherine (b. 1519–d. 1589), widowed at forty, was overcome with grief and dressed in black for the rest of her life. Ambassadors were struck by her pale complexion and stoutness as much as by her intelligence and stubbornness, the two aspects of her personality that Clouet strove to render.

While Paris was in the hands of the extremist Catholic League, Pierre de L’Estoile (b. 1546–d. 1611) assembled an album, Les Belles figures et drolleries de la Ligue, which was intended to show the League’s “wickedness, vanity, folly, and deception.” This woodcut recalls the great Parisian processions by “blue and white penitents” (so-called from the color of their garments), which Henry III instituted in 1583, and in which the king and his nobles participated.

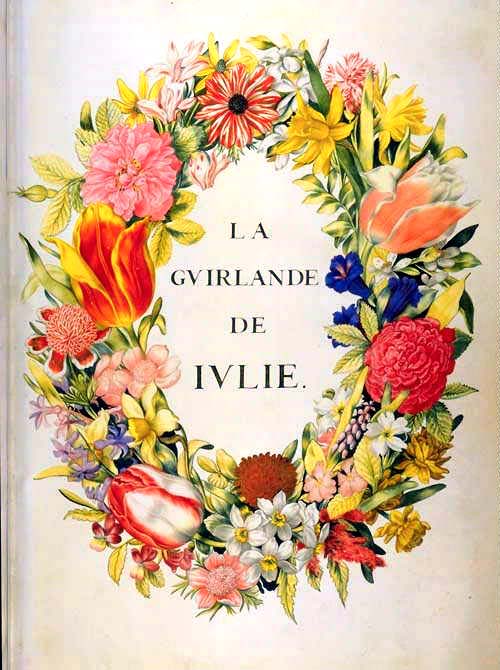

In 1634, Charles de Sainte-Maure, future Duke of Montausier (b. 1610–d. 1690), gave his beloved Lucine-Julie d’Angennes (b. 1607–d. 1671) a collection of verses. Prepared in collaboration with the most fashionable poets of his time, these verses exalted Julie’s beauty and other qualities through the theme of flowers. Faced with her apparent indifference, the marquis produced a more lavish version, exhibited here, which he gave Julie in 1641. Three years later, they were married.

Madeleine de Scudéry’s novel, Clélie, served as pretext for the description of acquaintances, stately residences, and palaces, and for dialogues based on actual conversations of her salon. The most immediate stir was created by the Carte du tendre (Map of Affection), engraved by François Chauveau and inserted in the first part of the novel. A salon game, the Map sparked a fad for “amorous geography” that took the form of allegorical almanacs and imaginary maps.

This manuscript, one of many from Mazarin’s library that entered the royal collection in 1668, is important for the period of the Il’Khans, the Mongol dynasty that reigned in Persia in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Rashîd al-Dîn, physician to King Abaqa (1265–1282), played a key role when the dynasty converted to Islam. He founded a mosque that became a center of important editorial production and cultural exchange, and published his own theological writings.

The costumes contributed to the dazzling entertainment of Le Ballet royal de la nuit, as did scenery changes and the ballet’s diverse characters. The ballet ends with the appearance of Aurore, who yields her place to the rising Sun, Apollo, played the first time by the young king Louis XIV. During his lifetime, Louis performed a wide range of roles—including plebeian characters. These drawings are of the Lute Player, the Warrior, and Apollo.

The Rise and Fall of the Absolute Monarchy: Grand Siècle and Enlightenment, 17th-18th Centuries

International recognition of French creativity in the arts, literature, and science formed an integral part of Louis XIV’s strategy to dominate European culture. Recognizing that political power lay in cultural superiority, and assisted by his minister, Colbert (Controller General of the Finances, 1662–1683), Louis XIV (1643–1715) initiated an all-encompassing cultural program designed to glorify the monarchy in his person. Fueled by state patronage, this cultural initiative channeled the creative forces of French elite culture into academies, luxury goods, industries, technology, engineering projects, and imperial expansion.

State control of culture reached unprecedented heights under Louis XIV, the Sun King (le Roi Soleil). Newly created academies in the arts and sciences generated heroic representations of the king that reinforced the royal religion. Increasing censorship targeted “scandalous” texts (for example, pornography) and political writings incompatible with absolute monarchy. Systematic purchases of treasures from ancient and modern cultures the world over enhanced the regime’s prestige. The need to reign supreme in cultural matters also spawned French Classicism, the crowning cultural achievement of France’s golden age under Louis XIV.

As the Sun King’s reign passed into its twilight years, some judged the social stability and routine he had created as oppressive to the individual spirit. A “counter-cultural” revolution under his successors, Louis XV (1715–1774) and Louis XVI (1774–1793), unleashed Enlightenment ideas and values which tore away at the theatrical and courtly foundations that Richelieu and Louis XIV had given the state. The cultural vitality of the realm shifted decisively from the royal court at Versailles to Paris. The increased role of the press, of reports of scientific and commercial activities, of exploration and discoveries, as well as the weekly meetings of academies and salons energized literary, artistic, and artisan circles.

The writer—whether a novelist, a scientist, or a philosopher describing a new and better society—became the guiding light of a culture that was enthusiastic about itself, eager for change, and increasingly beyond the control of royal censorship. In personal, cultural, and political identity, the writer evolved from a royal servant to an independent moral authority. The increasingly emancipated condition and subversive potential of authors reached their climax during the French Revolution (1789–1799) when the printed word played a mighty role in bringing down the Ancien Régime.

Louis XIV used medals to publicize the achievements of his government and of the institutions he founded. Drawing upon classical literature, artists elevated the technique of metal engraving to a new type of sculpture. The Little Academy, responsible for the invention and development of mottos and emblematic figures, oversaw the production of a series of “historical medallions.” The medals presented here are part of the série royale(royal series) of this Histoire métallique. The bust or head of Louis XIV, often clad in armor decorated with his symbol, the sun is featured on the obverse of each medal, while the reverse depicts the event or institution being commemorated. The sun is also featured in a medal which illustrates the king’s motto, Nec Pluribus impar (Not Unequal to Many). Louis IV’s birth is illustrated by a chariot in which Louis is riding. The academies founded to glorify the king are celebrated: two geniuses work busily in a sculpture and painting workshop, while Mercury engraves a laudatory epitaph on a bronze plaque. The abolition of dueling is illustrated by Justice, who is brandishing a scale and a sword. The expansion and embellishment of Paris is depicted by a turreted personification of the city, flanked by the two new city gates of Saint-Martin and Saint- Denis. Louis XIV set up the Royal School of Saint-Cyr, an aristocratic convent, in response to Mme. de Maintenon’s wish. The Sun King’s generosity is illustrated by Liberalitas (Liberality), sowing coins on the ground while his patronage of the arts is celebrated in a scene in which Liberalitas stands before Eloquence, Poetry, Astronomy, and History.

The Selenographia by the famous Polish astronomer Johannes Hevelius is the first lunar atlas. It also deals with the construction of lenses and telescopes and with the observation of celestial bodies in general. The author himself engraved the numerous text illustrations and plates, including the three large double-page maps of the moon and forty descriptions of the lunar phases. Upon receiving a royal pension, the grateful Hevelius sent Louis XIV the copy displayed here.

The Dutch War (1672–78), during which Louis XIV demonstrated strategic and tactical capabilities, provided the occasion for a skillful propaganda campaign by his historian-poets Boileau (b. 1636–d. 1711) and Racine (b. 1639–d. 1699). The war also produced the Campagnes de Louis XIVwhich contains maps of the operations and movements of French troops. Louis is illustrated here at the beginning of the volume dressed as a Roman emperor.

Because Dom Juan features a debauched, hypocritical noble who defies God, the play was quickly canceled and never published in Molière’s lifetime. This copy of the first edition of Molière’s complete works was published in 1682 and included Dom Juan, shortening its most offensive scene. The text was further revised by the censor. During the nineteenth century, Molière’s publishers produced a text of the play as close as possible to the original.

Télémaque, a pedagogical treatise based on the fourth book of the Odyssey, was part of an extensive educational curriculum designed by Fénelon, preceptor to Louis XIV’s grandson, the Duke of Burgundy. This “exceptional book,” in Voltaire’s words, emphasizes self-control, a return to the earth, and a reduction in spending. Despotic tendencies and a penchant for lavishness and war are discouraged. The volume opens with a portrait of Fénelon on a sheet of vellum.

This cameo shows the apotheosis or deification of a Roman emperor, a frequent subject of first-century art, taken to heaven by an eagle. The emperor, probably Claudius (A.D. 41–54), wears Jupiter’s breastplate and an imperial cloak, and is crowned with a laurel wreath by a Winged Victory. When Louis XIV acquired the cameo, the subject was incorrectly identified as the apotheosis of the imperial prince Germanicus, who died in the year 19.

The Book of Chinese Drawings was among the Condés’ collections of objets d’art seized in 1793 during the Revolution and deposited in the Bibliothèque Nationale. The book contains fifty-four plates, some of which are made up in long folding format, alternately depicting landscapes—in which Chinese people fish and play with kites—and floral compositions. The scene here depicts children playing with a stag beetle.

Some prominent French cartographers around the turn of the eighteenth century (and even later) believed that a Western Sea existed, to the west of Louisiana, which linked the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. Nicolas Bion (b. 1652–d. 1733), the King’s engineer for mathematical instruments, incorporated this imagined sea on two terrestrial globes, including the one exhibited here. He portrayed California as an island after having drawn it as a peninsula on an earlier globe.

After moving to Paris around 1735, Jacques-Christophe Leblon (b. 1667–d. 1741), a German miniaturist, painter, and engraver, obtained a royal warrant, a stipend, and lodging in the Louvre from Louis XV (1715–1774). The king also granted Leblon exclusive rights for color-engraving in France, on the express condition that he reveal his secret method to two royal commissioners. Leblon’s major work is this life-size bust portrait of his patron.

Even as a child, Louis XV was fascinated by geography. In 1718 a little print shop was set up in the Tuileries where the young king learned the rudiments of typography. There, Louis XV composed and, in part, printed this summary of Guillaume Delisle’s geography lessons, “Courses of the Principal Rivers and Streams of Europe.” Much later, Louis gave his mistress, the marquise de Pompadour (b. 1721–d. 1764), an elegantly bound copy of his childish “chef d’oeuvre.”

François Boucher’s painting of Venus at her toilet, assisted by cherubs, was designed to be hung in the private quarters of the marquise de Pompadour (b. 1721–d. 1764), mistress and friend of Louis XV (1715–1774). Jean-François Janinet invented and developed color aquatint engraving, and this is one example of his work. Thanks to this method, Janinet became the prime interpreter of fashionable painters like Boucher (b. 1703–d. 1770) and Jean-Honoré Fragonard (b. 1732–d. 1806).

This portrait of King Louis XV (1715–1774) is considered the masterpiece of engraving on stone in modern times, for the accuracy of the resemblance, the purity of the stone, and the high quality of the workmanship. Jacques Guay, the king’s engraver, skillfully used the three horizontal layers of stone in this cameo. Some parts were left dull while others were polished using a stone polisher according to a process invented by Guay.

This gold patera, used for drinking and in ceremonial libations, is decorated with imperial coins bearing the portraits of Roman sovereigns from Hadrian to Geta (the most recent dates from the year A.D. 209). A bas-relief in the center of the cup symbolizes the triumph of wine (Bacchus) over strength (Hercules). Found in Rennes in 1774, the patera was deposited by order of Louis XV (1715–1774) in the Department of Coins, Medals and Antiquities.

When his mother-in-law, the wife of the dethroned king of Poland, died in 1747, Louis XV (1715–1774) ordered a commemorative ceremony, pictured in this etching, in her honor at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. Observing the death of a member of the royal family by a highly codified funeral display, marked by Italian baroque symbolism, became a widespread custom in France during the seventeenth century. The ceremony glorified the deceased who underwent a veritable deification.

Saint-Simon’s account of Louis XIV’s death presents important figures from the last years of his reign, including members of competing political factions. Louis XIV’s death in 1715 unexpectedly opened a period of substantial political thaw, symbolized by the Duke of Saint-Simon’s proposals to increase participation in the central government, even if only by the nobility. The dawning Regency would witness a systematic effort to open up and increase flexibility of government.

In 1783, a French-language edition of the American Constitution was printed at the behest of Benjamin Franklin (b. 1706–d. 1790), to help his new country obtain the recognition of European courts. The model for the seal of the United States, depicted for the first time, appears in the title. Ironically, this copy born of a successful revolution was produced for Queen Marie-Antoinette (b. 1755–d. 1793), who blocked even moderate reform in France.

From Empire to Democracy: The Independence of Culture, 1799 to the Present

France and the United States are rightly considered the birth places of modern democracy. But while Americans have enjoyed the political and institutional stability of the “one and indivisible Republic” for over 200 years, the French since 1789 have experienced a succession of short-lived regimes: a Directoire, a consulate, two empires, two monarchies, and five republics, as well as the Vichy regime during World War II. In France, as one President of the Fifth Republic has noted, political crises tend to lead to institutional crises which threaten the regime itself. In such moments, the French have thrice heeded the call of charismatic and prestigious leaders (Napoleon I, Napoleon III, and Marshall Pétain) whose temperaments and politics paid short shrift to democracy. But twice they have turned to General Charles de Gaulle, who led the French Resistance against the Nazis and, in 1958, founded France’s current regime, the Fifth Republic. To date, it has proven a robust, prosperous and stable democracy.

The United States has not faced the threat of military invasion since the early nineteenth century. France, on the other hand, was overrun by foreign armies in 1814–1815 and later fought three major wars on her soil over seventy-five years (the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 and the two World Wars). Nor have the French been spared civil strife, including revolutions (1830, 1848), civil wars (1871, 1940–45), bitter wars of decolonization in Indochina and Algeria after World War II, and paralyzing nationwide strikes in 1968.

Such cataclysms have inflicted incalculable human and material losses. But they have also provided an inviting canvas of events and ideas for the creative brush strokes of poets, playwrights, novelists, painters, caricaturists, and statesmen — possible proof that the great artists of the modern era are motivated more by upheaval and injustice than by tranquil prosperity. The result: a remarkably rich and diverse culture, inspired by Enlightenment values and independent as never before from those who hold the reins of power.

Equally impressive has been the ultimate triumph of the revolutionary ideals of 1789: Liberty, Equality, Fraternity. That victory owes much to the French men and women who have defended freedom and democracy against domestic and foreign foes alike, often at the peril of their lives. Many of the items in this final section of Creating French Culture bear witness to their courage in the face of censorship and worse, and to their unwavering commitment to principles which Americans, too, have always cherished.

This painting is at the heart of a series of studies on the misfortunes of war and Napoleon’s retreat from Russia, which was to result in Géricault’s most famous lithograph, Return from Russia. In the middle of the icy plain a one-armed grenadier leads the exhausted horse of a blind cuirassier. The pain, resignation, and despair on their faces summarize this horrible disaster, survived by only a handful of Napoleon’s soldiers.

Daphnis and Chloë, a novel by the third-century B.C. Greek writer Longus, has been illustrated often throughout the centuries. In 1793, Pierre Didot the Elder, the scion of a dynasty of printers that revolutionized the aesthetic of the book in France, asked Pierre Prud’hon (b. 1758–d. 1823) to illustrate the novel. Prud’hon’s three drawings were supplemented by six from François Gérard (b. 1770–d. 1837). The copy exhibited here was produced for Imperial Marshal Andoche Junot (b. 1771–d. 1813).

Champollion’s five-volume Egyptian Pantheon drew heavily on his deciphering of hieroglyphics. For each god he provided abundant, accurate, and detached testimony of the classical authors, philological discussions, and excerpts from hieroglyphic texts, accompanied by drawings. Folio 88 reproduces the principal symbols of the Egyptian goddess Hathor whose motto on four columns is “lady of the offerings, eye of the sun residing in its disk, mistress of the heavens, spirit of all the gods.”

This set of four sketches by Charles Philipon (b. 1800–d. 1862), executed probably in 1831, begins with an accurate portrait of King Louis-Philippe (1830–1848) whose face the caricaturist gradually transformed into a pear. The pear, as a symbol of the soft, corpulent king, met with immediate success. Louis-Philippe, the so-called “Citizen King” was a favorite target of republican caricaturists until censorship was reinstated in September 1835.

Charles Marville, like Baldus, turned to photography from painting early in the Second Empire. Commissioned by the city of Paris, Marville began in 1858 to photograph the old streets destined to disappear during the urban renewal directed by Baron Georges Haussmann (b. 1809–d. 1891). He also photographed the City Hall. In this print of the oldest, central part of the façade, the richly sculpted Renaissance décor seems carved out by the light from the street lamps.

Hugo wrote Les Misérables, of which this is the autograph manuscript, between 1848 and 1861, to draw attention, as he noted in the preface, to “the degradation of man by poverty, the ruin of woman by hunger, the wasting of the child by night.” The work succeeded in drawing attention to the working conditions of women and children. Immediately successful, the novel inspired a stage version, parodies, an American film in 1909, and, more recently, a celebrated musical.

The premiere of Giuseppe Verdi’s (b. 1813–d. 1901) Aïda (March 22, 1880 at the Paris Opera) benefitted from the advice of Auguste-Edouard Mariette Bey (b. 1821–d. 1881), the famous Egyptologist. The scenery and costumes were designed with the greatest archeological precision. Exhibited here is the model for Scene I, Act I: a hall in the king’s palace. The entranceway in the middle leads to the hall of judgment, the gallery on the right to the prison of Radamès.

In December 1894, Captain Alfred Dreyfus, a French Jew falsely accused of treason, was sentenced to lifelong internment on Devil’s Island. In January 1898, the famous writer Emile Zola, convinced of Dreyfus’s innocence by mounting proof of a military cover up, drafted an open letter to President Félix Faure, denouncing the military establishment. The government filed suit against him, which, as Zola had predicted, ensured that “the truth is emerging and nothing can stop it” (folio 33).

In this collection of “Jewish stories” by Clemenceau (who became one of the falsely accused Captain Dreyfus’s staunchest defenders), candid accounts of the Jewish condition, collected during trips to Central Europe, counter-balanced more fanciful portraits (Baron Moses, Mayer the friendly crook). To illustrate the stories, Toulouse-Lautrec observed life in la Tournelle, the Jewish quarter of Paris. The original binding exhibited here is soberly Art Nouveau.

The conception and composition of Pelleas and Melisande, the only opera Debussy completed and one of the major works of the twentieth century, well illustrates the latent conflicts between dominant cultural authorities and an artist aware of the revolutionary character of his work. The autograph manuscript of the orchestra score exhibited here was used in the first performances and for the first edition of the orchestra score published in 1904.

The theme of this volume of Proust’s masterpiece is homosexuality, depicted through the experiences of the two main characters, Charlus and Albertine. Cities of the Plain fills seven of the twenty notebooks Proust used for the revised copies of the latter parts of the novel. The notebook displayed here corresponds to the beginning of Cities of the Plain II, which opens (fol. 14) with a high-society party given by the Princess of Guermantes.

Conclusion

From its inception, the French monarchy sought to expand state control over culture in order to consolidate its political power both nationally and internationally. This process reached its climax during the reign of Louis XIV. The death of the Sun King in 1715 marked a turning point in the relationship between power and culture in France. Since the Enlightenment, the “producers” of culture—artists, artisans, scientists and intellectuals—have gained an unprecedented degree of creative freedom. No longer servants of the state, they have become increasingly emancipated from those who wield political power. The democratization of culture, or what could be termed the spread of Enlightenment values, in turn made political democracy possible. Those values remain the cornerstone of contemporary French culture.

Behind this historic change in the power-culture relationship in France lies a historic continuity every bit as important. Today, as under Charlemagne twelve centuries ago, French culture is irrepressibly vital because it is open to creative forces from both within and beyond France’s borders. French kings, seeking beautiful objects to embellish royal power, did not hesitate to look abroad—in particular to Italy—for artists, architects, and craftsmen. The latter influenced, and in turn were influenced by their French counterparts. Similarly, many of the French writers, philosophers, artists, and politicians who contributed to the demise of the monarchy and later defended democracy, drew inspiration from sources and exchanges which transcended national boundaries. Over the centuries, these incomparably rich and diverse influences, filtered through the genius of French artists, craftsmen, and intellectuals, have come together, creating French culture.

Originally published by the United States Library of Congress, 09.08.1995, to the public domain.