Treatment has been uneven and deeply affected by social, racial, and political dynamics.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The history of drug addiction treatment in the United States is a complex narrative that reflects the changing social, medical, political, and legal attitudes toward drugs and addiction over time. From early punitive approaches and moral judgments to more recent movements emphasizing public health, harm reduction, and scientific understanding, the treatment of addiction has evolved alongside societal shifts in culture, race, class, and governance. This essay explores the major phases in the history of drug addiction treatment in the U.S., from the 19th century to the present day, showing how ideas about addiction and its treatment have developed over time.

Early Understandings: Moral Failing and Religious Reform (19th Century)

During the 19th century, the predominant understanding of drug addiction in the United States was largely framed through moral and religious lenses rather than medical or scientific perspectives. Addiction was perceived as a personal weakness or moral failing—a sign of poor character and a lack of self-discipline. This view was especially prevalent regarding alcohol consumption, which was the most common form of substance abuse at the time. Addiction was not yet recognized as a disease or a psychological disorder but was instead seen as a result of sinful behavior and personal irresponsibility. Consequently, the response to addiction was predominantly punitive and corrective, focusing on exhortation, repentance, and moral reform rather than medical intervention. This moralistic framework influenced both societal attitudes and policy approaches, leading to efforts aimed at eradicating vice through religious revival and social reform movements.1

Religious revivalism and the temperance movement became the primary social responses to addiction in the 19th century. Organizations like the American Temperance Society, founded in 1826, and later the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU), were instrumental in promoting abstinence and moral reform as antidotes to alcoholism and other forms of substance abuse. These groups framed addiction as a spiritual affliction that could be overcome by faith, repentance, and adherence to strict moral codes. The temperance movement gained considerable traction, influencing public opinion and eventually leading to legislative actions such as local and state prohibition laws. Religious leaders preached that the cure to addiction lay in the power of prayer, personal willpower, and community support rather than medical treatment, which was still in its infancy and often viewed skeptically.2

Opiate addiction, particularly to morphine and laudanum, was also widespread during the 19th century but was less publicly visible than alcoholism. Many individuals became addicted through the legitimate medical use of these drugs, which were commonly prescribed for pain relief and various ailments. The addiction that developed from such use was often regarded as a private failing rather than a public health issue. Physicians of the time struggled with how to treat opiate dependency; some prescribed incremental reductions or alternative medications, while others saw addiction as an intractable moral defect. Despite these challenges, the medical community began to take some interest in addiction, marking the earliest stirrings of medicalization, although this would not fully develop until later. Nevertheless, the stigma attached to addiction remained firmly rooted in the idea that it was caused by personal moral weakness.3

The 19th century also saw the rise of “inebriate homes” and asylums, which attempted to provide treatment for those struggling with addiction, primarily alcoholism. These institutions often combined moral reform with custodial care and rudimentary medical interventions, emphasizing discipline, confession, and spiritual renewal. While some of these facilities reported successes, many employed harsh methods such as isolation, physical restraint, and forced labor, reflecting the punitive attitudes of the era. The concept of addiction as a chronic disease had not yet emerged, and relapse was often seen as a failure of the patient’s character rather than a natural part of the disease process. Nonetheless, these early institutions laid important groundwork for later developments in addiction treatment, blending moral reform with early therapeutic approaches.4

The 19th century established the foundation for understanding addiction in the United States as a primarily moral and religious issue. This framework profoundly shaped the social and legal responses to addiction for decades. It was not until the late 19th and early 20th centuries that addiction began to be viewed more systematically through medical and scientific paradigms, setting the stage for the eventual development of modern addiction treatment. The legacy of the 19th century’s moralistic approach, however, persisted well into the 20th century, contributing to the stigma and criminalization that often accompanied addiction treatment efforts. Understanding this early context is crucial to appreciating the complex evolution of addiction treatment in the U.S.5

The Emergence of Medicalization and the Birth of Drug Regulation (Late 19th to Early 20th Century)

By the late 19th century, the understanding of drug addiction in the United States began to shift from purely moral and religious interpretations toward a more medicalized framework. This transition was influenced by advances in medical science, particularly the development of pharmacology and the burgeoning field of psychiatry. Physicians and scientists increasingly recognized addiction as a complex condition with physiological and psychological dimensions, rather than simply a moral failing. Early medical texts began to describe addiction as a chronic disease involving changes in brain chemistry and physical dependence, although these ideas were still in their infancy and often coexisted with older moralistic views.6 The work of medical pioneers such as Dr. Benjamin Rush, who earlier had advocated for understanding alcoholism as a disease, gained renewed attention and helped pave the way for a more scientific approach to addiction treatment.

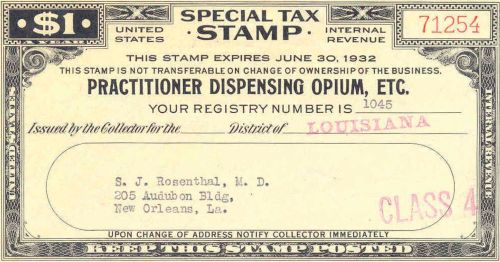

Alongside this growing medical interest, the widespread nonmedical use and abuse of opiates and cocaine alarmed public health officials and lawmakers. These substances, once widely available over the counter or by prescription, had become increasingly problematic due to their addictive properties and rising rates of dependence in the population. As a result, the early 20th century saw the birth of drug regulation in the United States, marked by a series of legislative acts aimed at controlling the manufacture, distribution, and sale of narcotics. The Harrison Narcotics Tax Act of 1914 was a landmark law that effectively regulated opiates and coca derivatives, requiring physicians and pharmacists to register and pay taxes on these substances. Although framed as a tax law, it functioned as a regulatory mechanism that limited access to addictive drugs and began the legal process of defining addiction within a medical-legal context.7

The medicalization of addiction during this period also influenced the development of specialized treatment facilities and approaches. Hospitals and sanatoria began to offer detoxification and rehabilitation services focused on both physical and psychological aspects of addiction. Treatments included gradually tapering drug dosages, the use of sedatives, and supportive therapies, all grounded in a medical model that emphasized disease and recovery. Furthermore, the mental health field started to incorporate addiction into its purview, with addiction increasingly classified alongside other psychiatric disorders. Institutions such as state hospitals began admitting patients with addiction-related illnesses, and specialized clinics emerged, marking a significant departure from the earlier inebriate homes’ moralistic custodial care.8 Nevertheless, the medical model was still limited by social stigma and incomplete scientific understanding, which sometimes led to inconsistent or ineffective treatments.

At the same time, the emerging regulatory framework intersected with evolving social and political attitudes toward drugs and addiction. The progressive era’s focus on social reform included concerns about public health and morality, which fueled support for tighter drug controls. This era also saw the beginnings of drug criminalization, as illicit drug use increasingly came to be viewed as a social threat requiring legal intervention. The connection between medicalization and regulation created tensions: while addiction was being recognized as a medical issue, enforcement policies often remained punitive, especially for marginalized populations. The combination of medical and legal perspectives laid the groundwork for modern drug policy, which balances treatment with law enforcement but often struggles with the conflicting goals of public health and criminal justice.9

By the early decades of the 20th century, the foundations of contemporary addiction treatment and drug control were firmly established. Medicalization provided a more humane and scientific rationale for understanding addiction, promoting the development of specialized treatments and professional interventions. Drug regulation laws such as the Harrison Act initiated government oversight of narcotics and helped standardize prescribing practices, although they also introduced legal penalties that complicated treatment access. This dual legacy of medicalization and regulation reflects a complex history marked by both progress and challenges, setting the stage for later developments in addiction medicine, public health policy, and drug enforcement that continue to shape responses to addiction today.10

Punishment Over Treatment: The Mid-20th Century

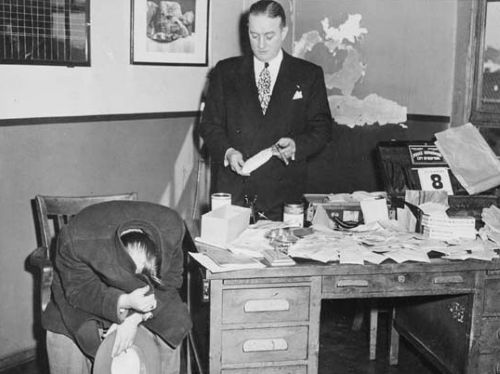

The mid-20th century in the United States marked a period when drug addiction was increasingly framed as a criminal justice issue rather than primarily a medical or social problem. Although medical advances had established addiction as a treatable condition by this time, public policy and popular attitudes shifted toward punitive measures emphasizing law enforcement and incarceration over treatment and rehabilitation. This shift was influenced by various social, political, and cultural factors, including the rise of illicit drug use in urban centers, fears about youth and minority communities, and a broader cultural anxiety about social order. Addiction became closely linked with crime and deviance, and policies increasingly favored punishment, reinforcing stigmatization rather than addressing underlying health concerns.11

One key element of this punitive turn was the enactment and expansion of harsh drug laws throughout the 1950s and 1960s. The Boggs Act of 1951 and the Narcotic Control Act of 1956 introduced mandatory minimum sentences for drug offenses, drastically increasing penalties for possession and trafficking of narcotics. These laws reflected a zero-tolerance approach and were often enforced disproportionately against African American and Latino populations, exacerbating racial disparities in the criminal justice system. Rather than promoting treatment or prevention programs, these policies prioritized incarceration and deterrence, contributing to the mass imprisonment of people with substance use disorders. This approach also hampered the development of comprehensive public health strategies and diverted resources away from addiction treatment programs.12

Despite the dominance of punishment-focused policy, some pockets of medical and therapeutic intervention persisted during this period. Methadone maintenance treatment, developed in the 1960s, represented a significant medical breakthrough for heroin addiction, offering a pharmacological method to reduce cravings and prevent withdrawal. Clinics providing methadone emerged as an alternative to incarceration for many addicts, particularly in urban areas with high rates of opioid dependence. However, methadone programs were often stigmatized and tightly regulated, and the broader social climate remained resistant to viewing addiction as a medical condition deserving of compassionate treatment. Many treatment facilities continued to operate with limited funding, and access to care was restricted, especially for marginalized communities.13

The mid-20th century also witnessed influential public campaigns and rhetoric that further criminalized drug users. The image of the “drug addict” was frequently conflated with moral degeneracy and social threat, portrayed in media and political discourse as dangerous, irresponsible, and morally corrupt. This narrative reinforced the idea that addiction was a choice or character flaw rather than a complex health issue. President Richard Nixon’s declaration of a “War on Drugs” in the late 1960s institutionalized this punitive framework at the federal level, linking drug control with law enforcement agencies and military-style tactics. These policies increased arrests and incarceration rates without addressing root causes or offering adequate treatment options, entrenching punishment as the primary response to addiction well into the latter half of the century.14

The mid-20th century represents a critical period in the history of drug addiction in the United States, when treatment and medical understanding were overshadowed by punitive policies and criminalization. While scientific and medical communities made important strides in understanding and treating addiction, the dominant social and political responses prioritized control and punishment. The legacy of this era continues to influence contemporary drug policy debates, particularly the tension between public health approaches and criminal justice strategies. Recognizing this historical context is essential for developing more balanced and effective responses to addiction today, emphasizing both compassionate care and social justice.15

Medicalization and the War on Drugs: 1960s–1980s

The period from the 1960s through the 1980s was marked by a complex interplay between the medicalization of addiction and the intensification of punitive drug policies embodied in the War on Drugs. On one hand, the medical and scientific communities made significant strides in understanding addiction as a chronic brain disease rather than a moral failing or purely criminal behavior. Advances in neurobiology, psychology, and pharmacology contributed to the growing consensus that addiction involved physiological changes affecting behavior and decision-making. During this time, methadone maintenance programs expanded, and new behavioral therapies were developed to support recovery. The establishment of the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) in 1974 symbolized a federal commitment to research and treatment, reflecting the medicalization trend.16 Yet, this progress coexisted uneasily with increasingly aggressive law enforcement efforts that disproportionately targeted drug users and dealers, often undermining public health initiatives.

The War on Drugs, formally launched under President Richard Nixon in the early 1970s and expanded under subsequent administrations, marked a decisive shift toward criminalization and punitive enforcement. Nixon famously described drug abuse as “public enemy number one,” prioritizing arrests and incarceration over treatment and prevention programs. This policy shift resulted in dramatic increases in drug-related arrests, particularly among minority and economically disadvantaged communities, contributing to mass incarceration. The Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 consolidated federal drug laws but also enhanced enforcement powers, reflecting the government’s dual focus on control and regulation. This period entrenched the idea of addiction as a criminal issue, despite growing evidence from medical research that treatment was essential for effective recovery.17

Despite the expansion of punitive policies, medical treatments for addiction continued to develop and gain institutional support. Methadone maintenance therapy became widely used for opioid dependence, offering an evidence-based approach to reduce harm and improve patient outcomes. Additionally, the emergence of new pharmacological treatments, such as naloxone for overdose reversal, marked important advances in medical care for addiction. Behavioral therapies and the twelve-step model, popularized by groups like Alcoholics Anonymous, were integrated into formal treatment settings. However, the stigma associated with addiction and the dominant punitive narrative limited the accessibility and public support for these medical treatments, especially in communities most affected by drug criminalization.18

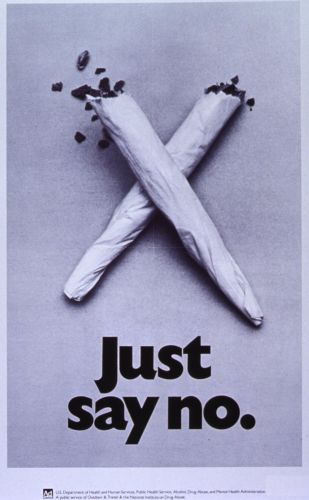

The tension between medicalization and criminalization also played out in public discourse and media representations. Drug addiction was often sensationalized as a social menace, and drug users were stigmatized as criminals or morally deficient individuals. This framing justified harsh sentencing laws and law enforcement tactics, while marginalizing treatment efforts. The media’s focus on crack cocaine in the 1980s, in particular, fueled racialized fears and punitive policies, leading to the Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986, which imposed severe mandatory minimum sentences and widened racial disparities in sentencing. This law symbolized the hardening of the War on Drugs approach, which prioritized punishment over rehabilitation and reflected political and social anxieties rather than scientific evidence about addiction and recovery.19

The 1960s to 1980s was a paradoxical era in the history of addiction treatment and drug policy. While addiction was increasingly understood as a medical disorder requiring treatment, policy makers simultaneously escalated punitive measures that criminalized users and restricted access to care. This dual legacy shaped the landscape of American drug policy for decades to come, embedding tensions between public health and criminal justice approaches. The period’s developments laid the groundwork for ongoing debates about how best to balance enforcement with compassionate, evidence-based treatment—debates that continue to influence addiction policy and practice into the present day.20

Harm Reduction and the Shift Toward Public Health (1990s–2000s)

The 1990s and early 2000s witnessed a notable shift in the United States toward viewing drug addiction through the lens of public health rather than exclusively as a criminal justice issue. This period saw the emergence and gradual acceptance of harm reduction strategies—pragmatic approaches aimed at minimizing the negative consequences of drug use rather than insisting on abstinence as the sole goal. Harm reduction sought to prioritize the health, dignity, and human rights of people who use drugs, challenging longstanding punitive policies that often exacerbated harm. Needle exchange programs (NEPs), supervised consumption sites, and expanded access to addiction treatment, including medication-assisted therapies like methadone and buprenorphine, became central tools in this new public health approach.21 The shift was driven by growing evidence of the failures of strict criminalization, alongside the escalating HIV/AIDS epidemic, which underscored the urgent need for policies that protected vulnerable populations.

The HIV/AIDS crisis was pivotal in catalyzing harm reduction efforts and the broader public health reorientation toward addiction. Injection drug use was identified as a major vector for HIV transmission, prompting public health officials and activists to advocate for NEPs as a lifesaving intervention. Despite initial political and public resistance—rooted in fears that needle exchanges might encourage drug use—research demonstrated that these programs reduced HIV spread without increasing drug consumption. This evidence helped legitimize harm reduction as a critical component of drug policy, marking a departure from zero-tolerance enforcement toward pragmatic health interventions. The Ryan White CARE Act of 1990 and subsequent federal funding streams began to incorporate support for HIV prevention among people who inject drugs, fostering integration between addiction treatment and infectious disease control.22

At the same time, the medical treatment of addiction gained greater legitimacy and accessibility. Medication-assisted treatments (MAT) such as methadone and, later, buprenorphine (approved by the FDA in 2002) became increasingly recognized as effective therapies for opioid dependence. Unlike earlier decades where treatment options were limited and stigmatized, the 1990s and 2000s saw efforts to integrate MAT into mainstream healthcare settings, including primary care clinics and community health centers. This integration was reinforced by a growing understanding of addiction as a chronic brain disorder requiring long-term management. Yet, despite these advances, significant barriers remained, including regulatory restrictions on prescribing medications and persistent stigma within both the medical community and the general public.23

The public health approach also emphasized prevention and education as essential components of addiction policy. Efforts to inform youth and communities about the risks of drug use expanded through school programs, public service campaigns, and community outreach. Unlike earlier moralistic or fear-based messaging, many prevention initiatives began to incorporate evidence-based practices focusing on resilience, social skills, and harm reduction education. Moreover, public health frameworks encouraged treating addiction as part of a broader spectrum of social determinants, including poverty, trauma, and mental health conditions. This more holistic view represented a paradigm shift away from blaming individuals toward addressing the environmental and structural factors that contribute to substance use disorders.24

Nevertheless, the harm reduction and public health shift coexisted with ongoing challenges and contradictions in U.S. drug policy. The criminal justice system remained heavily involved in responding to drug addiction, with millions incarcerated for drug offenses. The 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, for example, expanded punitive measures even as public health programs grew. Moreover, disparities in access to treatment and harm reduction services persisted along racial and socioeconomic lines. Activists and public health experts continually pushed for reforms that would prioritize health and equity over punishment, setting the stage for the evolving debates about drug legalization, decriminalization, and comprehensive addiction care that characterize the 21st century.25

The Opioid Epidemic and Modern Treatment Approaches (2010s–Present)

The 2010s to the present have been defined by the opioid epidemic, one of the most devastating public health crises in recent American history. Originating in the late 1990s and early 2000s with the widespread prescription of opioid painkillers such as oxycodone and hydrocodone, the epidemic escalated as misuse, addiction, and overdose deaths surged across diverse populations. Pharmaceutical companies initially assured the medical community that these medications had low addiction risks, which led to aggressive marketing and liberal prescribing practices. However, as rates of opioid use disorder (OUD) and fatal overdoses soared, it became clear that the medical establishment had significantly underestimated the dangers. The crisis evolved in waves, shifting from prescription opioids to heroin and then to synthetic opioids like fentanyl, which are far more potent and lethal. The epidemic has brought renewed attention to the limitations of past drug policies and the urgent need for comprehensive, evidence-based treatment and prevention strategies.26

Modern treatment approaches to the opioid epidemic have increasingly emphasized integrated, patient-centered care that combines medication-assisted treatment (MAT) with behavioral therapies and social support. MAT, which includes FDA-approved medications such as methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone, is now widely recognized as the gold standard for treating OUD. These medications reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings, improve retention in treatment, and decrease the risk of fatal overdose. The expansion of MAT access, through primary care providers and specialized clinics, represents a significant policy and clinical advancement compared to earlier eras when such treatments were limited and heavily stigmatized. Efforts to reduce regulatory barriers, such as the Ryan Haight Online Pharmacy Consumer Protection Act modifications and recent moves to allow more telemedicine prescribing of MAT, have further broadened treatment availability, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.27

Harm reduction strategies have also been critical components of the modern response to the opioid epidemic. Widespread distribution of naloxone, an opioid overdose reversal drug, has saved countless lives and is now accessible to first responders, community organizations, and even family members of those at risk. Syringe services programs (SSPs) continue to operate and expand in many regions, providing sterile equipment, safe disposal, and linkage to treatment and healthcare services. Supervised consumption sites, although controversial and limited in the U.S., have gained increased discussion as a possible tool to reduce overdose deaths and connect users with care. These harm reduction approaches reflect a public health orientation that prioritizes saving lives and reducing disease transmission even when abstinence is not immediately achievable.28

The opioid epidemic has also exposed and intensified disparities in addiction treatment and outcomes, particularly among racial, socioeconomic, and geographic lines. Rural communities have suffered disproportionately due to limited access to healthcare infrastructure, treatment providers, and harm reduction services. Similarly, racial minorities often face systemic barriers, including stigma, discrimination, and lack of insurance coverage, which hinder access to effective treatment. In response, there has been growing advocacy for equity-focused policies that address social determinants of health, expand Medicaid coverage for addiction services, and incorporate culturally competent care models. The crisis has thus spotlighted the importance of integrating addiction treatment into broader healthcare reform efforts and social justice initiatives to ensure that effective care reaches all populations in need.29

The ongoing opioid epidemic has spurred innovative research and policy reform aimed at transforming the landscape of addiction treatment. New medications targeting opioid receptors, vaccines to prevent relapse, and digital therapeutics are being developed and tested. Federal and state governments have allocated billions of dollars through legislation such as the SUPPORT for Patients and Communities Act (2018) to enhance prevention, treatment, and recovery services. At the same time, there is increasing recognition that addressing addiction requires multidisciplinary collaboration involving healthcare providers, law enforcement, social services, and community stakeholders. While challenges remain—including persistent stigma, funding gaps, and evolving drug supply dynamics—the lessons learned from the opioid epidemic continue to reshape how society approaches addiction as a chronic health condition deserving comprehensive, compassionate care.30

Conclusion: A Continuing Evolution

The treatment of drug addiction in the United States has evolved from a moralistic and punitive system to one that increasingly recognizes addiction as a chronic health condition requiring evidence-based care. Yet, this evolution has been uneven and deeply affected by social, racial, and political dynamics. Today’s approaches emphasize harm reduction, medication-assisted treatment, integrated behavioral care, and community-based support. But achieving equitable access and overcoming stigma remain critical challenges. The future of addiction treatment in America will depend not only on advances in science and medicine but also on political will, public compassion, and a commitment to social justice.

Appendix

Endnotes

- David T. Courtwright, Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 18–20.

- David F. Musto, The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), 25–28.

- Courtwright, Dark Paradise, 22–23.

- William R. Miller and Kathleen A. Carroll, Rethinking Substance Abuse: What the Science Shows, and What We Should Do About It (New York: Guilford Press, 2006), 12–13.

- Musto, The American Disease, 35–37.

- Courtwright, Dark Paradise, 45-48.

- Musto, The American Disease, 60-65.

- Richard Davenport-Hines, The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Social History of Drugs (New York: W.W. Norton, 2002), 130–133.

- Courtwright, Dark Paradise, 53–57.

- Musto, The American Disease, 70–74.

- Emily Dufton, Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America (New York: Basic Books, 2017), 90–95.

- Michelle Alexander, The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness (New York: The New Press, 2010), 44–50.

- David T. Courtwright, Addiction and Narcotic Control: Medical Advances and Social Policy in the Twentieth Century, Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 506–510.

- Ethan Nadelmann, Cops Across Borders: The Internationalization of U.S. Criminal Law Enforcement (University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001), 152–155.

- Alex S. Vitale, The End of Policing (London: Verso, 2017), 110–115.

- Nora D. Volkow and Thomas R. Insel, “The War on Drugs: Is It Over Yet?” New England Journal of Medicine 370, no. 22 (2014): 2063–2065.

- Alexander, The New Jim Crow, 78-85.

- Courtwright, Dark Paradise, 109-115.

- Jonathan P. Caulkins, “The Crack Cocaine Epidemic,” in The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders, ed. Kenneth J. Sher (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016), 428–432.

- Nadelmann, Cops Across Borders, 203-210.

- Alexander B. Barker, Harm Reduction and Public Health: The Evolution of Drug Policy (New York: Routledge, 2010), 56–62.

- Holly A. Nicoll and Nancy E. Loustaunau, “Needle Exchange Programs and the Fight Against HIV/AIDS in the United States,” American Journal of Public Health 91, no. 10 (2001): 1587–1590.

- Nora D. Volkow et al., “Medication-Assisted Therapies for Opioid Addiction,” New England Journal of Medicine 370, no. 22 (2014): 2063–2072.

- Jeffrey A. Smith and Laura M. Johnson, “Prevention and Public Health Strategies in Drug Addiction,” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 34, no. 3 (2008): 243–250.

- Michelle M. Brown, Drug Policy and Justice: Conflicts and Convergences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 88–95.

- Anna Lembke, Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021), 23–37.

- Nora D. Volkow et al., “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: Treating a Chronic Disease,” Annual Review of Medicine 73 (2022): 319–332.

- Sarah E. Wakeman and Josiah D. Rich, “Harm Reduction in the Era of the Opioid Epidemic,” New England Journal of Medicine 379, no. 1 (2018): 2–5.

- Elizabeth A. Jacobs and Lilia Cervantes, “Addressing Health Disparities in the Opioid Epidemic,” Health Affairs 38, no. 10 (2019): 1707–1713.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, “The Opioid Crisis and Response,” HHS.gov, last modified March 2023, https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Health-Research-and-Development-for-Opioid-Crisis-National-Roadmap-2019.pdf.

Bibliography

- Alexander, Michelle. The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness. New York: The New Press, 2010.

- Barker, Alexander B. Harm Reduction and Public Health: The Evolution of Drug Policy. New York: Routledge, 2010.

- Brown, Michelle M. Drug Policy and Justice: Conflicts and Convergences. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Caulkins, Jonathan P. “The Crack Cocaine Epidemic.” In The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use and Substance Use Disorders, edited by Kenneth J. Sher, 420–438. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Courtwright, David T. “Addiction and Narcotic Control: Medical Advances and Social Policy in the Twentieth Century.” Journal of American History 89, no. 2 (2002): 500–525.

- Courtwright, David T. Dark Paradise: A History of Opiate Addiction in America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001.

- Davenport-Hines, Richard. The Pursuit of Oblivion: A Social History of Drugs. New York: W.W. Norton, 2002.

- Dufton, Emily. Grass Roots: The Rise and Fall and Rise of Marijuana in America. New York: Basic Books, 2017.

- Jacobs, Elizabeth A., and Lilia Cervantes. “Addressing Health Disparities in the Opioid Epidemic.” Health Affairs 38, no. 10 (2019): 1707–1713.

- Lembke, Anna. Drug Dealer, MD: How Doctors Were Duped, Patients Got Hooked, and Why It’s So Hard to Stop. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2021.

- Miller, William R., and Kathleen A. Carroll. Rethinking Substance Abuse: What the Science Shows, and What We Should Do About It. New York: Guilford Press, 2006.

- Musto, David F. The American Disease: Origins of Narcotic Control. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Nadelmann, Ethan. Cops Across Borders: The Internationalization of U.S. Criminal Law Enforcement. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2001.

- Nicoll, Holly A., and Nancy E. Loustaunau. “Needle Exchange Programs and the Fight Against HIV/AIDS in the United States.” American Journal of Public Health 91, no. 10 (2001): 1587–1590.

- Smith, Jeffrey A., and Laura M. Johnson. “Prevention and Public Health Strategies in Drug Addiction.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 34, no. 3 (2008): 243–250.

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. “The Opioid Crisis and Response.” HHS.gov. Last modified March 2023. https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Health-Research-and-Development-for-Opioid-Crisis-National-Roadmap-2019.pdf.

- Vitale, Alex S. The End of Policing. London: Verso, 2017.

- Volkow, Nora D., et al. “Medication-Assisted Therapies for Opioid Addiction.” New England Journal of Medicine 370, no. 22 (2014): 2063–2072.

- Volkow, Nora D., et al. “Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: Treating a Chronic Disease.” Annual Review of Medicine 73 (2022): 319–332.

- Volkow, Nora D., and Thomas R. Insel. “The War on Drugs: Is It Over Yet?” New England Journal of Medicine 370, no. 22 (2014): 2063–2065.

- Wakeman, Sarah E., and Josiah D. Rich. “Harm Reduction in the Era of the Opioid Epidemic.” New England Journal of Medicine 379, no. 1 (2018): 2–5.

Originally published by Brewminate, 06.04.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.