Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In the practice of religion, a cult image is a human-made object that is venerated or worshipped for the deity, spirit or daemon (not to be confused with demon) that it embodies or represents. In several traditions, including the ancient religions of Egypt, Greece and Rome, and modern Hinduism, cult images in a temple may undergo a daily routine of being washed, dressed, and having food left for them. Processions outside the temple on special feast days are often a feature. Religious images cover a wider range of all types of images made with a religious purpose, subject, or connection. In many contexts “cult image” specifically means the most important image in a temple, kept in an inner space, as opposed to what may be many other images decorating the temple.

The term idol is often synonymous with cult image.[1][2][3] In cultures where idolatry is not viewed negatively, the word idol is not generally seen as pejorative, such as in Indian English.[4]

Ancient Near East and Egypt

The use of images in the Ancient Near East seems typically to have been similar to that of the ancient Egyptian religion, about which we are the best-informed. Temples housed a cult image, and there were large numbers of other images. The ancient Hebrew religion was or became an exception, rejecting cult images despite developing monotheism; the connection between this and the Atenism that Akhenaten tried to impose on Egypt has been much discussed. In the art of Amarna Aten is represented only as the sun-disk, with rays emanating from it, sometimes ending in hands.

Cult images were a common presence in ancient Egypt, and still are in modern-day Kemetism. The term is often confined to the relatively small images, typically in gold, that lived in the naos in the inner sanctuary of Egyptian temples dedicated to that god (except when taken on ceremonial outings, say to visit their spouse). These images usually showed the god in their sacred barque or boat; none of them survive. Only the priests were allowed access to the inner sanctuary.

There was also a huge range of smaller images, many kept in the homes of ordinary people. The very large stone images around the exteriors of temples were usually representations of the pharaoh as himself or “as” a deity, and many other images gave deities the features of the current royal family.

Classical Greece and Rome

All ancient Greek temples and Roman temples normally contained a cult image in the cella. Access to the cella varied, but apart from the priests, at the least some of the general worshippers could access the cella some of the time, though sacrifices to the deity were normally made on altars outside in the temple precinct (temenos in Greek). Some cult images were easy to see, and were what we would call major tourist attractions. The image normally took the form of a statue of the deity, typically roughly life-size, but in some cases many times life-size, in marble or bronze, or in the specially prestigious form of a Chryselephantine statue using ivory plaques for the visible parts of the body and gold for the clothes, around a wooden framework. The most famous Greek cult images were of this type, including the Statue of Zeus at Olympia, and Phidias’s Athena Parthenos in the Parthenon in Athens, both colossal statues now completely lost. Fragments of two chryselephantine statues from Delphi have been excavated.

The acrolith was another composite form, this time a cost-saving one with a wooden body. A xoanon was a primitive and symbolic wooden image, perhaps comparable to the Hindu lingam; many of these were retained and revered for their antiquity. Many of the Greek statues well-known from Roman marble copies were originally temple cult images, which in some cases, such as the Apollo Barberini, can be credibly identified. A very few actual originals survive, for example the bronze Piraeus Athena (2.35 metres high, including a helmet).

In Greek and Roman mythology, a “palladium” was an image of great antiquity on which the safety of a city was said to depend, especially the wooden one that Odysseus and Diomedes stole from the citadel of Troy and which was later taken to Rome by Aeneas. (The Roman story was related in Virgil’s Aeneid and other works.)

Abrahamic Religions

Overview

Members of Abrahamic religions identify cult images as idols and their worship as idolatry – the worship of hollow forms. The Book of Isaiah gave classic expression to the paradox inherent in the worship of cult images:

Their land also is full of idols; they worship the work of their own hands, that which their own fingers have made.— Isaiah 2.8, reflected in Isaiah 17.8.

One could avoid such a degrading paradox by adopting the early Christian idea that miraculous icons were not made by human hands, acheiropoietoi. Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Christians make an exception for the veneration of images of saints – they distinguish such veneration from adoration or latria.

The disparaging of man-made (as opposed to divine) works as idols can provide a useful pejorative, especially in religious discussions.[5]

The word idol entered Middle English in the 13th century from Old French idole adapted in Ecclesiastical Latin from the Greek eidolon (“appearance”, extended in later usage to “mental image, apparition, phantom”) a diminutive of eidos (“form”).[6] Plato and the Platonists employed the Greek word eidos to signify perfect immutable “forms”.[7] One can, of course, regard such an eidos as having a divine origin.[8][9]

Christianity

Christian images that are venerated are called icons. Christians who venerate icons make an emphatic distinction between “veneration” and “worship”.

The introduction of venerable images in Christianity was highly controversial for centuries, and in Eastern Orthodoxy the controversy lingered until it re-erupted in the Byzantine Iconoclasm of the 8th and 9th centuries. Religious monumental sculpture remained foreign to Orthodoxy. In the West, resistance to idolatry delayed the introduction of sculpted images for centuries until the time of Charlemagne, whose placing of a life-size crucifix in the Palatine Chapel, Aachen was probably a decisive moment, leading to the widespread use of monumental reliefs on churches, and later large statues.

The Libri Carolini, a somewhat mis-fired Carolingian counter-blast against imagined Orthodox positions, set out what remains the Catholic position on the veneration of images, giving them a similar but slightly less significant place than in Eastern Orthodoxy.

The intensified pathos that informs the poem Stabat Mater takes corporeal form in the realism and sympathy-inducing sense of pain in the typical Western European corpus (the representation of Jesus’ crucified body) from the mid-13th century onwards. “The theme of Christ’s suffering on the cross was so important in Gothic art that the mid-thirteenth-century statute of the corporations of Paris provided for a guild dedicated to the carving of such images, including ones in ivory”.[10]

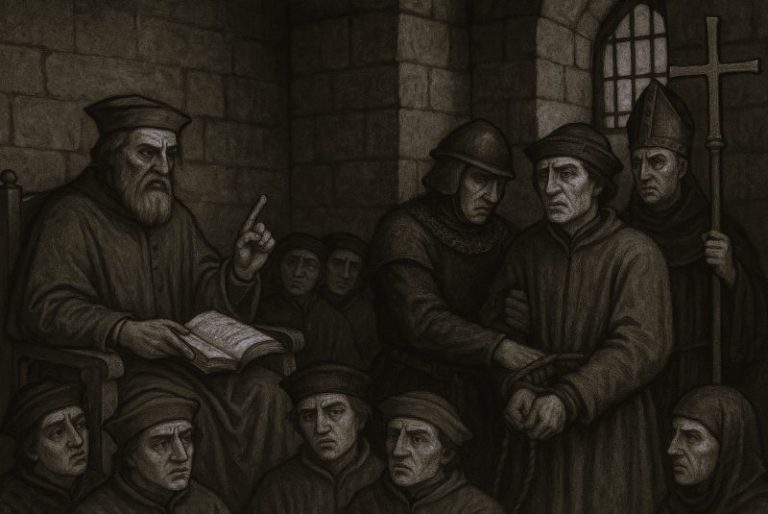

The 16th-century Reformation engendered spates of venerable image smashing, especially in England, Scotland, Ireland, Germany, Switzerland, the Low Countries (the Beeldenstorm) and France. Destruction of three-dimensional images was normally near-total, especially images of the Virgin Mary and saints, and the iconoclasts (“image-breakers”) also smashed representations of holy figures in stained glass windows and other imagery. Further destruction of cult images, anathema to Puritans, occurred during the English Civil War. Less extreme transitions occurred throughout northern Europe in which formerly Catholic churches became Protestant. In these, the corpus (body of Christ) was removed from the crucifix leaving a bare cross and walls were whitewashed of religious images.

Catholic regions of Europe, especially artistic centres like Rome and Antwerp, responded to Reformation iconoclasm with a Counter-Reformation renewal of venerable imagery, though banning some of the more fanciful medieval iconographies. Veneration of the Virgin Mary flourished, in practice and in imagery, and new shrines, such as in Rome’s Santa Maria Maggiore, were built for Medieval miraculous icons as part of this trend.

Islam

Towards the end of the pre-Islamic era in the Arabian city of Mecca; an era otherwise known by the Muslims as جاهلية, or al-Jahiliyah, the pagan or pre-Islamic merchants of Mecca controlled the sacred Kaaba, thereby regulating control over it and, in turn, over the city itself. The local tribes of the Arabian peninsula came to this centre of commerce to place their idols in the Kaaba, in the process being charged tithes. Thus helping the Meccan merchants to incur substantial wealth, as well as insuring a fruitful atmosphere for trade and intertribal relations in relative peace.

The number and nature of deities in the pre-Islamic mythology are parallel to that of other polytheistic cultures. Some have been official Gods others of a more private character.

Muhammad’s preaching incurred the wrath of the pagan merchants, causing them to revolt against him. The opposition to his teachings grew so volatile that Muhammad and his followers were forced to flee Mecca to Medina for protection; leading to armed conflict and triggering many battles that were won and lost, which finally culminated in the conquest of Mecca in the year 630. In the aftermath, Muhammad did three things. Firstly, with his companions he visited the Kaaba and literally threw out the idols and destroyed them, thus removing the signs of Jahiliyyah from the Kaaba. Secondly, he ordered the construction of a mosque around the Kaaba, the first Masjid al-Haram after the birth of Islam. Thirdly, in a magnanimous manner, Muhammad pardoned all those who had taken up arms against him. With the destruction of the idols and the construction of the Masjid al-Haram, a new era was ushered in; facilitating the rise of Islam.

Indian Religions

Hinduism

The garbhagriha or inner shrine of a Hindu temple contains an image of the deity. This may take the form of an elaborate statue, but a symbolic lingam is also very common, and sometimes a yoni or other symbolic form. Normally only the priests are allowed to enter the chamber, but Hindu temple architecture typically allows the image to be seen by worshippers in the mandapa connected to it (entry to this, and the whole temple, may also be restricted in various ways).

Hinduism allows for many forms of worship[11] and therefore it neither prescribes nor proscribes worship of images (murti). In Hinduism, a murti[12] typically refers to an image that expresses a Divine Spirit (murta). Meaning literally “embodiment”, a murti is a representation of a divinity, made usually of stone, wood, or metal, which serves as a means through which a divinity may be worshiped.[13] Hindus consider a murti worthy of serving as a focus of divine worship only after the divine is invoked in it for the purpose of offering worship.[14] The depiction of the divinity must reflect the gestures and proportions outlined in religious tradition.

Jainism

In Jainism, the Tirthankaras (“ford-maker”) represent the true goal of all human beings.[15] Their qualities are worshipped by the Jains. Images depicting any of the twenty four Tirthankaras are placed in the Jain temples. There is no belief that the image itself is other than a representation of the being it represents. The Tirthankaras cannot respond to such veneration, but that it can function as a meditative aid. Although most veneration takes the form of prayers, hymns and recitations, the idol is sometimes ritually bathed, and often has offerings made to it; there are eight kinds of offering representing the eight types of karmas as per Jainism.[16] This form of reverence is not a central tenet of the faith.

Appendix

Notes

- “Idol” in the American Heritage Dictionary (2016.)”. Ahdictionary.com. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- “Idol” in Merriam–Webster (2017)”. Merriam-webster.com. 2019-01-15. Retrieved 2019-01-29.

- “Idol” in the Oxford Living Dictionaries (2017).

- “Idol”, Harper’s Bible Dictionary, ed. Paul J. Achtemier, San Francisco, Harper and Row, 1985; but readily used by, for example, Swami Tejomayananada, in his Hindu culture, An Introduction, p. 66, Chinmaya Mission, 9788175971653

- For example: Mahoney, Daniel J. (2018). “The Humanitarian Subversion of Christianity and Authentic Political Life”. The Idol of Our Age: How the Religion of Humanity Subverts Christianity. New York: Encounter Books. Retrieved 16 Jan 2019.

Humanitarianism as Comte first proclaimed it is an ‘idol’ of the first order at the service of a soul-destroying illusion.

- Harper, Douglas. “idol”. Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Smith, P. Christopher (2002). “Is Plato a Metaphysical Thinker? Rereading the ‘Sophist’ after the Middle Heidegger”. In Welton, William A. (ed.). Plato’s Forms: Varieties of Interpretation. Lanham, Maryland: Lexington Books. p. 243. Retrieved 16 Jan 2019.

[…] what is seen and known is no longer the original transient physical thing coming to pass either temporally or locally but the static metaphysical eidos or intelligible ‘look’ a physical thing has about it, the conceptual form known by the mind’s eye and of which the physical thing is now only a particular instance.

- Smith, John Clark (1992). The Ancient Wisdom of Origen. Bucknell University Press. p. 19. Retrieved 16 Jan 2019.

The Platonic Forms become, in fact, thoughts of the Divine Mind […].

- Popper, Karl (2012) [1945]. The Open Society and its Enemies (7 ed.). London: Routledge. p. 146, 158. Retrieved 16 Jan 2019.

[…] the divine originals, the Forms or Ideas […] the divine world of Forms or Ideas […].

- Metmuseum

- Vaswani, J.P. (2002). Hinduism: What You Would Like to Know About. Sterling Publishers Pvt. Ltd. p. 12.

Hinduism also teaches us that all forms of worship are acceptable to God. We may use idols; we may go to temples; we may recite set prayers; we may offer a simple form of worship with flowers and a lamp; or we may perform an elaborate puja with set rituals; we may sing bhajans or join a kirtan session or we can just close our eyes and meditate upon the light within us.

- “pratima (Hinduism)”. Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2011.

- Klostermaier, Klaus K.A Survey of Hinduism. 1989 pp. 293–5

- Kumar Singh, Nagendra. Encyclopaedia of Hinduism, Volume 7. 1997, pp. 739–43

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1953), Joseph Campbell (ed.), Philosophies Of India, London, E.C. 4: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd, p. 182

- “Hansa sutaria”, Jain rituals & ceremonies, Jaina, archived from the original (Doc) on 2007-06-28

Further Reading

- Dick, Michael Brennan, ed. (1999). Born in Heaven, Made on Earth: The Making of the Cult Image in the Ancient Near East. Eisenbrauns.

- Hill, Marsha (2007). Gifts for the gods: images from Egyptian temples. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Hundley, Michael B. (2013). Gods in Dwellings: Temples and Divine Presence in the Ancient Near East. Society of Biblical Literature.

- Walls, Neal H., ed. (2005). Cult Image and Divine Representation in the Ancient Near East. American Schools of Oriental Research.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 01.15.2006, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.