Enclosure demonstrates how profoundly law and markets can reshape social life without overt coercion. Collapse becomes structural rather than accidental.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: Peasant Agriculture and the Myth of Inevitable Modernization

The transformation of European agriculture between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries is often narrated as a story of progress. Enclosure, market integration, and commercial farming are portrayed as rational responses to demographic pressure and economic opportunity. Within this framework, the disappearance of the peasant farm appears inevitable, a necessary sacrifice on the path toward efficiency and growth. Such accounts obscure the degree to which agrarian change was shaped by deliberate political choices that privileged certain forms of production while rendering others unsustainable.

Peasant agriculture in early modern Europe was not an archaic remnant awaiting replacement. It was a functional system grounded in mixed farming, communal land use, and reciprocal obligations that spread risk across households and seasons. Small farms balanced subsistence with limited market participation, relying on access to commons, customary rights, and shared resources to survive volatility. These arrangements did not maximize output in the abstract, but they prioritized continuity and social stability in environments where failure carried existential consequences.

The erosion of this system was neither spontaneous nor uniform. Enclosure advanced through law, policy, and enforcement that redefined land as exclusive property and recast customary use as inefficiency. States and landed elites justified these changes through the language of improvement, productivity, and national prosperity. Yet the burdens of restructuring fell disproportionately on small producers who lacked capital buffers and political leverage. What was framed as modernization functioned in practice as a transfer of resilience from communities to consolidated landholders.

The collapse of the peasant farm in early modern Europe was not the natural outcome of economic evolution but the result of state-backed restructuring that favored scale over survival. By examining enclosure, trade shocks, and the social consequences of dispossession, the discussion challenges narratives that equate consolidation with inevitability. Instead, it situates agrarian collapse within a longer historical pattern in which policy choices reshape agriculture by determining who bears risk and who is protected from it.

The Pre-Enclosure Agrarian World: Peasant Farms and Communal Survival

Before enclosure reshaped the countryside, agrarian life across much of Europe was organized around peasant farms embedded in communal systems of land use. These farms were rarely large, but they were integrated into a landscape governed by customary rights rather than exclusive ownership. Open-field systems divided arable land into strips worked by individual households, while meadows, forests, and wastes were held in common. Survival depended less on maximizing output than on maintaining access to a shared ecological and social infrastructure.

Communal rights were not peripheral to peasant agriculture. They were essential. Grazing animals on common land, collecting firewood, gathering fodder, and accessing water allowed households to survive fluctuations in harvest and income. These rights functioned as informal insurance, distributing risk across the community and reducing dependence on markets. A poor harvest did not immediately translate into starvation or land loss because commons provided supplementary resources that softened the impact of scarcity.

Peasant farms were typically mixed operations, combining grain cultivation with livestock, garden plots, and small-scale craft or seasonal labor. This diversity was not a sign of inefficiency but a deliberate strategy to manage uncertainty. Livestock provided manure, traction, and food reserves. Gardens supplemented diets and reduced reliance on purchased goods. Seasonal rhythms structured labor in ways that balanced household needs against environmental constraints. Production was calibrated to survival rather than expansion.

Social organization reinforced this economic logic. Village communities enforced norms governing land use, crop rotation, and access to shared resources. Decisions were collective, negotiated through custom and local authority rather than imposed by distant markets. While inequalities existed, the system constrained extreme accumulation by tying land use to participation in the community. Independence was real but relational, sustained through reciprocal obligation rather than isolation.

The pre-enclosure agrarian world was neither static nor idyllic, but it was resilient in ways later systems would not be. Its strength lay in the distribution of risk and the integration of households into a web of shared rights. When enclosure dismantled these arrangements, it did more than reorganize land. It stripped away the communal mechanisms that had allowed small farms to endure volatility, transforming survivable hardship into permanent dispossession.

Enclosure as Policy: Law, Power, and the Rewriting of Land Rights

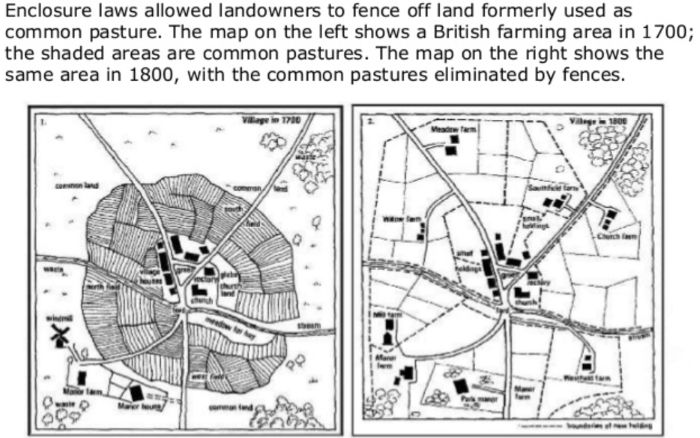

Enclosure did not arise from spontaneous economic evolution but from deliberate legal transformation. In England especially, the conversion of common land into exclusive property proceeded through statutes, court decisions, and administrative enforcement that systematically redefined land rights. Parliamentary enclosure acts formalized processes that had already begun at local levels, authorizing surveys, reallocations, and the extinguishing of customary claims. What had once been governed by shared practice was now rendered legible to the state as alienable property.

Law played a decisive role in this transition. Customary rights, long recognized through usage and local authority, were increasingly reframed as inefficient or obstructive. The legal language of improvement and productivity justified enclosure as a rational correction rather than a dispossession. Compensation, when offered, was often inadequate or inaccessible to smallholders who lacked the resources to navigate legal proceedings. Through procedural legitimacy, enclosure achieved what outright expropriation might have provoked resistance to accomplish.

Power determined whose interests the law served. Landed elites dominated Parliament, local commissions, and courts, shaping enclosure in ways that favored consolidation. The asymmetry was stark. Those with capital and influence could acquire enclosed land, absorb transitional costs, and reorganize production. Small farmers, dependent on commons for survival and lacking political leverage, bore the consequences. The law did not target peasants explicitly, but it restructured the environment in which their survival had been possible.

The rewriting of land rights marked a profound shift in the relationship between state and countryside. Enclosure translated political authority into economic advantage, converting shared landscapes into instruments of accumulation. By legalizing exclusion, the state transformed land from a social resource into a commodity governed by market logic. The collapse of peasant farming was not an unintended side effect of this process. It was the predictable outcome of policy choices that elevated property rights over communal survival.

Trade Shocks, Markets, and the Exposure of Small Farms

Market integration exposed peasant farms to forces they were never designed to withstand. As early modern states expanded trade networks and oriented production toward regional and international markets, price volatility became a defining feature of agrarian life. Grain prices fluctuated sharply in response to war, weather, speculation, and shifts in demand. For large landholders with diversified holdings and access to credit, these swings represented manageable risk. For small farmers operating at the edge of subsistence, they were existential threats.

Trade shocks magnified this vulnerability. Periods of export expansion encouraged specialization, particularly in wool and cash crops, displacing food production and tying rural livelihoods to distant markets. When demand collapsed or imports undercut domestic prices, small producers absorbed the shock immediately. They lacked storage capacity, capital reserves, and bargaining power. What might have been a temporary downturn became a permanent loss of land as farmers sold plots to meet obligations or fell into debt they could not repay.

War intensified these pressures. Military conflict disrupted trade routes, raised taxes, and requisitioned supplies, all while removing labor from farms. Inflation and scarcity followed, further destabilizing rural households. States often prioritized urban provisioning and commercial interests, insulating cities and exporters at the expense of countryside producers. Small farms, already weakened by enclosure, faced a convergence of market exposure and political neglect that accelerated their disappearance.

Markets did not merely reveal inefficiencies in peasant farming. They reallocated risk in ways that favored scale. Price volatility rewarded those who could wait out losses and punished those who could not. In this environment, consolidation was not an accident but an outcome structured by exposure. Trade integration transformed uncertainty into a selective force, systematically removing small farms while leaving larger commercial operations intact. The collapse of peasant agriculture reflected not market failure but market design aligned with unequal capacity to survive disruption.

From Landholders to Laborers: The Social Consequences of Dispossession

The loss of land transformed more than patterns of production. It redefined social identity. For peasant households, landholding had anchored economic independence, household authority, and local standing. Dispossession severed this foundation, converting producers into laborers whose survival depended on wages, charity, or patronage. The transition was not gradual for those affected. Once access to commons and small plots disappeared, households crossed a threshold from autonomy to precarity that few could reverse.

Rural displacement reshaped the countryside itself. Former smallholders remained in villages as landless laborers or migrated in search of work, creating a surplus workforce that depressed wages and increased competition for seasonal employment. Labor became casual, insecure, and highly sensitive to market conditions. Employers benefited from this abundance, while workers faced chronic instability. What had once been reciprocal relationships embedded in village life were replaced by transactional arrangements governed by necessity rather than custom.

Urban migration intensified these pressures. Cities such as London absorbed growing numbers of displaced rural families, but urban economies were ill equipped to provide stable livelihoods. Employment was irregular, housing overcrowded, and public assistance limited. Many households relied on a patchwork of day labor, informal trade, and charitable relief. The move to the city did not represent upward mobility so much as a shift from rural insecurity to urban dependence, with survival contingent on access to fragile networks.

Dispossession also altered family and gender dynamics. Wage dependence reshaped household roles, pulling women and children more fully into precarious labor markets. Domestic production, once supplemental to farming, became essential to survival. The loss of land removed a critical buffer that had allowed households to smooth income across seasons. Without it, economic shocks reverberated more sharply, increasing vulnerability to illness, unemployment, and hunger.

The social consequences of enclosure extended far beyond the redistribution of acreage. Dispossession reorganized class structure, expanded the ranks of the working poor, and entrenched inequality. By transforming independent producers into dependent laborers, enclosure reshaped both rural and urban societies. The collapse of the peasant farm did not merely change how food was produced. It reconfigured the relationship between labor, security, and survival in early modern Europe.

Urban Survival: Allotments, Gardens, and Cooperative Food Networks

As rural dispossession accelerated, urban households developed survival strategies that sought to recreate fragments of agrarian security within city spaces. Kitchen gardens, small plots on the urban fringe, and informal cultivation of unused land became common features of working-class life. These practices did not represent a rejection of urbanization but an adaptation to its limits. Food production, even at minimal scale, offered a measure of autonomy in environments where wages were uncertain and prices volatile.

Allotments emerged as a particularly significant response. In England and parts of continental Europe, small garden plots were allocated to laboring families by parishes, employers, or philanthropic organizations. These spaces allowed households to grow vegetables, keep small livestock, and supplement meager diets. Allotments reduced reliance on markets without restoring full agrarian independence. They functioned as stabilizers rather than replacements, buffering hunger during downturns while leaving broader economic vulnerability intact.

Cooperative food networks extended this logic beyond individual plots. Informal sharing arrangements, mutual aid societies, and neighborhood-based exchange helped distribute resources more evenly among precarious households. These networks relied on trust, proximity, and reciprocal obligation rather than contract. In many cities, they overlapped with guild remnants, religious communities, or parish structures that coordinated assistance during crises. Cooperation became a practical necessity in environments where neither wages nor relief could be relied upon consistently.

Women played a central role in sustaining these systems. Household food production, preservation, and distribution often fell to women whose labor bridged the gap between income and subsistence. Gardens, kitchens, and informal markets became sites of economic activity that mitigated the loss of land-based production. Yet this labor remained undervalued and invisible in official accounts of economic transformation, masking the extent to which urban survival depended on uncompensated household work.

Despite their importance, urban subsistence strategies faced structural limits. Space constraints, pollution, insecure tenure, and competing land uses restricted expansion. Allotments could be revoked, gardens displaced, and cooperative networks disrupted by redevelopment or regulation. These arrangements survived at the margins of urban economies, tolerated but rarely protected. Their fragility underscored the difference between coping mechanisms and structural solutions.

Urban gardening and cooperative food networks reveal both resilience and constraint. They demonstrate that displaced populations actively sought to preserve food security and dignity under adverse conditions. At the same time, they confirm that such strategies could not substitute for systemic agricultural production or restore the independence lost through enclosure. These practices sustained life, not livelihoods. They were responses to dispossession, not reversals of it.

State Rhetoric and Economic Reality: Praising the Farmer While Breaking the Farm

Early modern states spoke warmly of agriculture even as their policies dismantled the conditions that sustained small farmers. Political discourse celebrated husbandry, improvement, and rural virtue, presenting agriculture as the moral backbone of the nation. Pamphlets, sermons, and policy statements praised diligence in the fields and framed productive land use as a patriotic duty. This rhetoric projected continuity and care, masking the extent to which restructuring was underway.

In practice, state action favored capitalized landholders and commercial production. Legal support for enclosure, tolerance of speculative land markets, and the prioritization of export-oriented agriculture redistributed resilience upward. Policies designed to stabilize grain supplies for cities or secure revenue streams for the state routinely shifted risk onto rural producers. Small farmers were exhorted to adapt, improve, and compete, yet denied the material protections that adaptation required. Praise substituted for protection.

The contradiction was sustained through language that equated consolidation with progress. Improvement literature recast communal practices as backward and inefficient, legitimizing exclusion as modernization. By framing enclosure and market exposure as necessary reforms, states insulated themselves from responsibility for dispossession. The farmer remained a symbolic figure in national narratives, even as the peasant farm itself was rendered economically untenable.

This disjunction between rhetoric and reality was not accidental. It allowed states to claim allegiance to agrarian values while advancing policies aligned with fiscal stability and elite interests. The result was a moral economy that honored agriculture in theory while undermining it in practice. Small farmers were praised as cultural icons at the very moment their survival was treated as expendable. The collapse of the peasant farm occurred not in defiance of state ideology, but beneath its protective language.

Structural Continuity: From Enclosure to Modern Agricultural Policy

The enclosure movement did not conclude with the eighteenth century. It established structural principles that continue to shape agricultural policy long after the hedges were laid and the commons extinguished. Central among these principles is the concentration of resilience. Systems are organized to protect capitalized producers while exposing smaller operators to market volatility. Consolidation is treated as efficiency, and survival outside scale is framed as an anachronism. The logic first codified through enclosure persists as an organizing assumption rather than a historical exception.

Modern agricultural policy reproduces this pattern through different instruments. Subsidies, credit access, insurance schemes, and trade agreements consistently favor large operations capable of navigating administrative complexity and absorbing delayed returns. Small farmers encounter regulatory and financial thresholds that function much like early enclosure laws, legal in form but exclusionary in effect. Risk remains individualized, while protection is institutionalized. What changed is not the outcome, but the language used to justify it.

Tariffs and uneven relief programs illustrate this continuity with particular clarity. Trade disruptions raise input costs and destabilize markets, striking small producers first. Emergency assistance is often slow, conditional, or calibrated to output levels that privilege scale. Relief stabilizes production without preserving producers, mirroring earlier interventions that sustained food supply while allowing dispossession to proceed. The pattern is familiar. Crisis accelerates consolidation, and policy responds by managing consequences rather than correcting structure.

The persistence of enclosure dynamics reveals that agrarian collapse is not an unintended byproduct of modernization. It is a foreseeable result of policy choices that treat consolidation as rational and vulnerability as inefficiency. Early modern Europe demonstrates that dismantling peasant agriculture does not require hostility toward farmers. It requires only a framework that consistently favors capital, scale, and resilience while allowing survival to remain a private burden. The continuity between enclosure and modern agricultural policy lies not in repetition of form, but in the endurance of this governing logic.

Conclusion: When Survival Is Treated as Inefficiency

The enclosure of early modern Europe reveals that agrarian collapse is rarely the result of neglect or ignorance. It follows from systems that redefine survival itself as a problem to be solved. Peasant farming did not fail because it was unproductive, but because it prioritized continuity, reciprocity, and risk sharing over scale and profit. When policy recast these qualities as inefficiencies, it transformed resilience into a liability and independence into an obstacle.

Enclosure demonstrates how profoundly law and markets can reshape social life without overt coercion. By converting customary rights into exclusion and communal use into trespass, states dismantled the material foundations of peasant survival while preserving the appearance of legality and progress. Dispossession unfolded through procedure rather than violence, allowing restructuring to proceed with minimal disruption to elite interests. The result was not merely a new agricultural order, but a redefinition of who agriculture was for.

The social consequences of this transformation were enduring. Independent producers became wage laborers, urban migrants, or recipients of relief, while food production concentrated in fewer hands. Urban survival strategies such as allotments and cooperative networks sustained life but could not restore autonomy. As in earlier agrarian collapses, coping replaced stability, and adaptation substituted for protection. What was lost was not simply land, but the capacity of households to withstand disruption without surrendering independence.

Early modern Europe offers a cautionary lesson that resonates beyond its own time. When survival is treated as inefficiency, collapse becomes structural rather than accidental. Enclosure shows that agricultural modernization without protection does not eliminate vulnerability. It reallocates it. History’s warning is not that change must be resisted, but that policy determines who bears its costs. Where resilience is reserved for those with scale, societies trade long-term stability for short-term efficiency, repeating patterns whose consequences have been visible for centuries.

Bibliography

- Allen, Robert C. Enclosure and the Yeoman: Agricultural Development of the South Midlands, 1450–1850. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Beier, A. L. Masterless Men: The Vagrancy Problem in England 1560–1640. London: Methuen, 1985.

- Bloch, Marc. French Rural History. Translated by Janet Sondheimer. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1931.

- Braudel, Fernand. The Wheels of Commerce. Vol. 2 of Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century. Translated by Siân Reynolds. New York: Harper & Row, 1982.

- Bucholz, Robert. Early Modern England 1485-1714: A Narrative History. London: Blackwell, 2004.

- Burnett, John. Plenty and Want: A Social History of Food in England from 1815 to the Present Day. London: Routledge, 1968.

- Clark, Gregory. A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- De Vries, Jan. The Economy of Europe in an Age of Crisis, 1600–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1976.

- DuPlessis, Robert S. “Transitions To Capitalism In Early Modern Europe: Economies In The Era Of Early Globalization, c. 1450 – c. 1820 The Era Of Early Globalization, c. 1450 – c. 1820.” History Faculty Works (Swarthmore College), 2019.

- Friedmann, Harriet, and Philip McMichael. “Agriculture and the State System: The Rise and Decline of National Agriculture.” Sociologia Ruralis 29, no. 2 (1989): 93–117.

- Hindle, Steve. On the Parish? The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c. 1550–1750. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- McCloskey, Deirdre N. The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006.

- Melton, Edgar. “The Peasants of Ottobeuren, 1487-1726: A Rural Society in Early Modern Europe.” Journal of Interdisciplinary History 38:1 (2007): 122-123.

- Neeson, J. M. Commoners: Common Right, Enclosure and Social Change in England, 1700–1820. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

- Polanyi, Karl. The Great Transformation: The Political and Economic Origins of Our Time. Boston: Beacon Press, 1944.

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531–1782. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

- Thompson, E. P. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage, 1966.

- Wood, Ellen Meiksins. The Origin of Capitalism: A Longer View. London: Verso, 2002.

- Wrigley, E. A., and R. S. Schofield. The Population History of England 1541–1871: A Reconstruction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981.

Originally published by Brewminate, 02.17.2026, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.