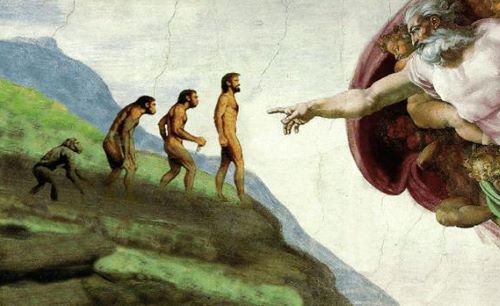

Science and religion are intractable competitors.

By Dr. Jeffrey Schloss

Distinguished Professor of Biology

Westmont College

The current blood feud between religious science-deniers and New Atheist religion-bashers sells a lot of books. For many people, religious or not, the polarization brings to mind Mercutio’s “a plague o’ both your houses!” But Jerry A. Coyne’s new book, “Faith vs. Fact,” rejects accommodationist bipartisanship. He asserts that “science and religion are incompatible, and you must choose between them.”

He argues this for two reasons. The first is that the major attempts to support religion through science, or even merely to avoid conflict with science, just don’t work. The second and stronger claim is that they can’t work because the very ways in which science and faith seek to understand the world are intrinsically opposed.

Concerning the first claim, Coyne surveys a wide range of attempts to accommodate science and religion. He rightly points out weaknesses, taking on cult science such as the Israelite origin of Native Americans, opposition to vaccination, and denial of global warming. He lampoons accommodationist salve that masks rather than solves problems. He scorns, for example, biologist and philosopher Francisco Ayala’s claim that evolution solves the problem of evil because evolution, not God, is responsible. And he has no patience with simplistic assurances that science and religion cannot ever conflict because their rightful domains don’t overlap at all.

One argument is that our universe shows evidence of design in that the physical laws and constants that govern it precisely match what is required for life. Coyne quite fairly acknowledges that the universe does display such fine tuning for a number of constants. But he also rightly points out that we really don’t know how probable (or improbable) such a universe is. However, he speculates that even if the probability is very low, that doesn’t prove the believers’ case. If there are many universes (as some cosmologists hypothesize), a life-friendly universe might be likely. “If you deal a huge number of bridge hands,” he notes, “one that’s perfect, or close to it, becomes probable.”

Another argument claims that universal moral beliefs and radically sacrificial behaviors can’t be explained by natural processes and thus require God. In an excellent brief treatment of the underlying science, Coyne describes a range of current explanations of the natural origins of moral beliefs and behaviors. Life can work well when we do good. He also points out that although sacrificial altruism is a thorny evolutionary problem, there are provisional (though still debated) naturalistic proposals for how it can emerge.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE WASHINGTON POST