If the disease of freedom fatigue is cyclical, then its cure must be generational. History warns that rights erode not through sudden violence, but through long neglect.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

In recent years, a curious silence has settled over the American civic landscape: the once-vigorous commitment to defending constitutional rights appears to be ebbing. Citizens who once rallied around the First Amendment, the vote, the rule of law now seem less inclined to engage, question, protest, or even vocalize concern when those protections are threatened. I call this phenomenon freedom fatigue, a state in which the effort of maintaining liberty outpaces the will to do so.

What lies behind this fatigue? Historians and psychologists alike point to cycles of heroic reform followed by backlash, institutional retrenchment, and public withdrawal. From the dismantling of Reconstruction-era guarantees to the suppressed dissent of the McCarthy period, and now to the 2025 era under President Donald Trump, we observe not just recurring rights-erosion, but a recurring societal loss of appetite for active defense. What follows explores how the weariness of safeguarding freedom has become a structural obstacle (not just occasionally, but recurrently) and asks what happens when the civic energy to defend rights dissipates.

The First Cycle: Post-Reconstruction Disillusionment

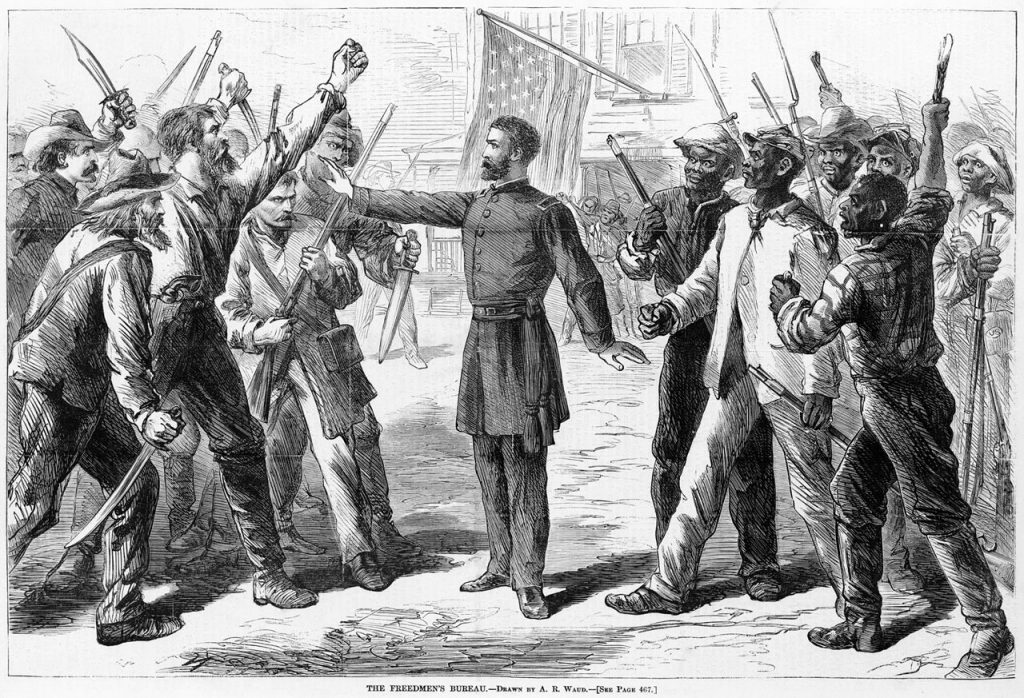

After the Civil War, America stood briefly at the threshold of a true democratic expansion. The Reconstruction Amendments (the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth) promised equality before the law, citizenship for the formerly enslaved, and protection of the right to vote. For a fleeting moment, the country appeared committed to building a republic that matched its rhetoric. But by the late 1870s, that promise had unraveled. The federal government withdrew troops from the South, ending Reconstruction and leaving Black Americans to face a campaign of terror, disenfranchisement, and legal regression that would last nearly a century.

Between 1865 and 1877, Black political participation reached unprecedented levels, only to collapse under the weight of violence and indifference. The federal retreat allowed white supremacist militias to overturn elected governments and replace multiracial democracy with Jim Crow apartheid. Courts, once the arbiters of justice, became instruments of racial control. The U.S. Supreme Court’s Plessy v. Ferguson decision in 1896 codified segregation, declaring it “separate but equal” and legitimizing the abandonment of equality as a civic value.

Psychologically, the collapse of Reconstruction instilled a pattern that would repeat through American history: moral exhaustion following reform. The abolitionist generation’s moral intensity gave way to disillusionment and fatigue. Many citizens, North and South, wanted simply to move on, to stop “fighting old battles.” The desire for normalcy triumphed over the duty to enforce justice. In this silence, the machinery of repression grew louder. Freedom fatigue, in this first great cycle, took the form of resignation, the collective shrug that follows the shattering of idealism.

The Second Cycle: The McCarthy Era and the Fear of Dissent

In the years after World War II, Americans faced a different kind of exhaustion, not from civil war or racial violence, but from fear. The Cold War introduced an age of suspicion where loyalty became a test of citizenship, and dissent was equated with treason. Senator Joseph McCarthy’s crusade against alleged communists blurred the line between vigilance and paranoia, as government agencies, universities, and film studios turned inward to purge themselves of perceived subversives. The period’s irony was stark: in defending freedom from foreign ideology, Americans allowed fear to erode it at home.

The National Archives records that congressional hearings publicly shamed hundreds of citizens, often without evidence, and ruined careers in journalism, academia, and entertainment. Institutions complied not through force, but fatigue, the weary instinct to protect themselves rather than resist. The chill was psychological as much as political. Citizens learned that silence, not courage, ensured safety. The exhaustion of constant vigilance bred compliance, and fear became a habit.

That climate also encouraged a kind of moral numbness. Americans, relieved by the postwar boom and preoccupied with prosperity, chose comfort over confrontation. Civic courage was quietly redefined as conformity. As historian Ellen Schrecker has written in her work on McCarthyism, repression succeeded not because most Americans approved of it, but because so few opposed it. Freedom fatigue in the 1950s did not manifest as despair but as distraction, a willingness to trade liberty for stability and call it peace.

The pattern mirrored the end of Reconstruction: a burst of reform and idealism, followed by the slow erosion of vigilance and a longing for normalcy. Once again, rights contracted not through dramatic overthrow, but through collective retreat. Each generation, it seems, must decide whether fatigue or freedom will win its patience. In the McCarthy years, fatigue won by quiet consent.

And that consent left a legacy. The political machinery of loyalty tests and ideological purges did not disappear; it adapted. The lessons of silence and fear lingered in the American psyche, reemerging whenever crisis narratives demand obedience. By the time the twenty-first century arrived, the ghosts of McCarthy’s committees had become familiar, warning that freedom fatigue, once internalized, never truly sleeps.

The Third Cycle: The Present Moment in 2025

In 2025, the United States stands at a pivotal moment in which civic fatigue and institutional strain coincide. Scholars observe a growing pattern of executive enlargement, weakening of checks and balances, and shrinking space for dissent in what is described as a case of democratic backsliding. While this shift is still uneven, its symbolic and material consequences are profound: rights on paper increasingly depend on the stamina of citizens and institutions to enforce them.

Public-opinion data reflect the fatigue creeping into civic life. A 2025 survey found that 73% of Americans view government corruption as a “critical threat,” and 65% regard weakening democracy in the U.S. similarly. Yet high concern does not automatically translate into action; when the burden of defense becomes endless, many simply withdraw. That retreat is a marker of freedom fatigue: the sensation that preservation of rights has become too constant, too personal, too exhausting.

The institutional dynamics feed this fatigue. According to the Varieties of Democracy Institute, for instance, the United States is flagged as a country “on track to lose its democracy status,” reflecting measurable declines in horizontal accountability, civil liberties and judicial independence. In such a setting, the typical modes of rights-defense (protest, legal challenge, watchdog journalism) face steeper headwinds. When the players who once held the line are drained or embattled, the citizens’ role becomes heavier.

The psychological dimension of this moment cannot be overlooked. When rights are under pressure not only from external opponents, but from the wear of defending them everyday, the civic center can fray. Activism becomes professionalized, institutionalized, or exhausted; the average citizen may say: “I have done my part,” or “What more can I do?” That sense of individual weariness is a feature, not a bug, of this cycle. The danger is that when attention drops and vigilance fades, the rights that survive on paper risk decaying in practice.

The Fourth Cycle: Patterns of Erosion and the Psychology of Fatigue

Looking across these three eras (Reconstruction, McCarthyism, and the present) a pattern emerges that is more psychological than political. Freedom in the American tradition has never simply been a legal status; it is a practice that requires attention, endurance, and faith in the possibility of reform. When those reserves run low, rights become brittle. The historical record shows that fatigue, not force, is often what weakens liberty’s foundation. Apathy, despair, or distraction can achieve what authoritarianism alone cannot, the quiet surrender of vigilance.

Psychologists describe this as learned helplessness: when repeated effort produces few results, people stop trying. The pattern appeared after Reconstruction, when Black citizens fought for rights that courts refused to enforce; it surfaced again during the McCarthy era, when defending free speech became a liability; and it recurs today, when decades of political gridlock convince voters that activism no longer matters. Each period teaches the same lesson: without visible victories, citizens lose the will to fight.

There is also a cultural mechanism at work, what sociologists call normalization. The longer restrictions persist, the more ordinary they feel. Segregation once shocked moral sensibilities, then became routine. Government surveillance once outraged the public, then became ambient. Freedom fatigue thrives in that transition from shock to acceptance. When intrusion and injustice no longer feel urgent, their permanence becomes tolerable.

The cyclical nature of this fatigue suggests that the problem is not merely political leadership but civic psychology. Americans, inheritors of a revolutionary mythology, often imagine freedom as self-sustaining, something achieved once and guaranteed thereafter. But in practice, liberty demands constant, sometimes exhausting maintenance. Each generation inherits not a finished republic, but a fragile experiment. The lesson of history is that democracy’s collapse rarely begins with a coup; it begins when a weary people stop defending what they no longer believe can be lost.

The Fifth Cycle: Breaking the Pattern

If the disease of freedom fatigue is cyclical, then its cure must be generational. History warns that rights erode not through sudden violence, but through long neglect. The only lasting remedy is renewal, a deliberate act of civic reawakening that rebuilds faith in participation and shared responsibility. Every expansion of liberty in American history has begun this way: when ordinary citizens, refusing exhaustion, decided that retreat was no longer an option. The challenge now is to rediscover that energy before complacency hardens into acceptance.

Restoring that stamina begins with knowledge. Civic education in the United States has withered for decades, replaced by partisan noise and disinformation. Relearning the architecture of rights (how they function, how they can fail) is the first defense against their erosion. Teaching constitutional literacy strengthens long-term democratic resilience. Understanding the mechanics of freedom makes apathy harder to justify.

But education alone cannot sustain engagement. Citizens also need visible proof that participation still matters. Public trust in government remains near historic lows, a void that breeds indifference. Reversing that trend requires institutions willing to be accountable and transparent, showing that civic energy produces results. Small, local wins, a school board made more inclusive, a city council held to ethical standards, can recharge a national sense of agency far more effectively than distant federal victories.

Ultimately, the antidote to freedom fatigue is not outrage, but endurance. Democracies survive when citizens make vigilance a habit rather than a crisis response. Fatigue, after all, is not failure; it is a signal that the work of freedom is ongoing. From the ashes of Reconstruction to the silence of McCarthyism and the disillusionment of 2025, the pattern is clear: liberty falters when Americans confuse comfort with peace. The promise of self-government endures only when the people who inherit it refuse to rest.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.