By Nicole Budrovich

Curatorial Assistant

J. Paul Getty Museum

Introduction

In 1977, just three years after the newly built Getty Villa opened its doors to the public, Chicago resident Norman J. Cowan and his family visited the museum during a trip to California. The museum must have made an impression. Upon returning home, Cowan wrote a thank you note to the Getty curator and added, “You will recall our conversation regarding Roman Nails […] Please let me know by return mail if you are still interested in my gift of these nails for display purposes.”

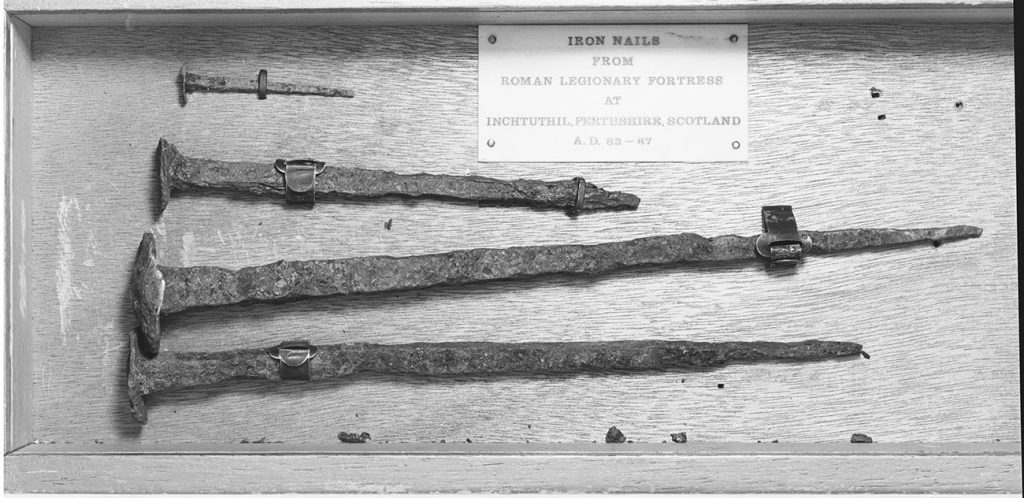

Ancient iron nails would hardly be considered Art, but they could offer insights on Roman metalworking, so in 1978 the donation was accepted. An old photo shows the nails in a wooden display box with a clear top and a label affixed inside that reads, “Iron nails from Roman legionary fortress at Inchtuthil, Perthshire, Scotland A.D. 83–87.”

Although described as “from Scotland” on early acquisition paperwork, an updated report from 1990 poses some doubts, listing the origin as “Scotland?” and adds, “these four nails are said to have been found at the site of a Roman Legionnaire Camp.” As part of our ongoing efforts to research the provenance of our collection, I set out to see if this bizarre origin story could be verified.

First, I went to storage to check the current status of the nails, and found they are still housed in the same wooden box Norman Cowan donated forty years ago, and the “Inchtuthil, Perthshire, Scotland” label was still attached.

Old display cases or stands can be a treasure trove for provenance research—they may preserve stickers or be compared against similar examples with documented collection histories.

The old object label itself was the first point of departure, pointing us to an unexpected story about a modern interest in ancient nails.

A Roman Military Fortress, Abandoned and Rediscovered

Although not a household name, Inchtuthil (pronounced Inch-tweth-ill) is well-known to those interested in Roman Britain and military history. Located in northern Scotland, Inchtuthil is the most northerly military fort in the Roman Empire. Construction began around AD 83, and parts of the fortress were still being built when it was dismantled and abandoned only a few years later in AD 87. Military needs had changed, and the Roman legion assigned to Inchtuthil was ultimately stationed further south. For the next two thousand years, the site remained relatively undisturbed.

Although abandoned, the garrison at Inchtuthil was known by the mid-1500s and documented on maps of Roman military sites in the 1700s and 1800s. Excavations in the 1950s led by Sir Ian Richmond have yielded the most information about the site—the remains of barracks, a temporary headquarters building, four senior officers’ houses, a hospital, a workshop, and six granaries.

A Million Iron Nails

Then, in the summer of 1960 a surprising discovery was made—a hoard of nearly a million iron nails.

Weighing almost ten tons, the iron nails were found buried in a pit, twelve feet deep, and covered by six feet of gravel. These extreme burial measures were likely to prevent the local Scottish tribes from finding the iron and reusing it for weapons. Iron rarely survives from antiquity, but since the hoard was buried as one big mass, the outer nails corroded forming a protective crust that preserved the internal core.

The nails were excavated and sent to the National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland in Edinburgh and then transferred to Colville’s, a steelworks, to be counted, measured, and studied. There were at least 875,428 nails ranging from 2 ½ inches to 15 inches long—the hoard likely contained over a million nails originally.

The discovery hit the local papers, and even the earliest reports speculated on what would be done with these iron nails. In 1961 the Birmingham Daily Post quoted Sir Ian Richmond, “Even if a set were sent to every museum on earth there would still be many tons left over.”

Richmond himself donated a set of five nails to his university museum in 1962 and a selection of nails was given to the National Museum of Scotland, along with other finds from the site.

Dispersal and Sale of the Nails

The excavations of Inchtuthil needed funding, and the nails were sold off individually for five shillings each or as a set of five with a commemorative label for 25 shillings (about $33 today). More than 10,000 requests poured in from around the world. “Newsboys and bishops bought them, so did company directors and Japanese scholars. Publicans put them over bars, and hundreds of Americans wrote for sets,” the Birmingham Daily Post reported at the time.

Overwhelmed with applications, the Iron and Steel Institute closed the list in late 1962, and sales were stopped by October 1963, claiming that no more nails fit for distribution were left. It took a few years to process the requests, which were eventually fulfilled.

In 1963, The Times, a newspaper out of Shreveport, Louisiana, reported that 11-year-old Ronald James had read about the Inchtuthil discovery two years prior, and “posted a letter with $4 to an Oxford archaeology professor. Time passed and Ronald thought he was the victim of a hoax, but Saturday he received the nails in the mail.”

The Getty nails, housed in a presentation case with a commemorative label, date to these 1962 sales.

From Factories to Department Stores: Where Are These Box Sets Now?

Some nails, like the Getty example, have been donated to museums—the Smithsonian, the Penn Museum, and the Classics Museum of Australian National University. Certainly more museums must have Inchtuthil nails lurking in storage, waiting to be catalogued. It seems many of these box sets are still with collectors, periodically offered for sale through online auctions.

(If you know of any iron nails from Inchtuthil in your local museum or an old family collection, let us know in the comments!)

The dispersed box sets account for most of the medium and large nails, a tiny fraction of the total hoard, while the rest of the small nails were to be melted down and recycled. The steelworks retained some of the nails for study, and in the 1980s mounted a few hundred in resin blocks, which were given out as promotional British Steel paperweights.

The bulk of the nail hoard, it would seem, had been recycled. However, during the 1990s and early 2000s, many more Inchtuthil nails showed up in some bizarre venues—department stores, mail order, and newspaper advertisements, suggesting that at least some of the nails were not recycled after all.

In California, Englishman Steve Ward reportedly bought 30,000 Inchtuthil nails, “as a sideline to his sausage distribution business, British Banger Corp.” and opened “A.D. Discoveries” near San Diego, hoping to market the ancient curios to Americans (Los Angeles Times, November 24, 1990). Santa Barbara’s Nordstrom department store ordered 50 of these nails, each “sealed in Lucite and resting in a velvet-lined oak box, to offer for Christmas,” at a whopping price of $189 each.

In 2004 the American Historic Society offered Inchtuthil nails for sale in their oddest form yet—“each carefully crafted into an 18-inch necklace” for $39.95. The advertisement claimed there was an “extremely limited supply” of 65,000 nails, and states “demand is expected to be huge.” Today, Inchtuthil nails can be found for sale through eBay, Etsy, and various online auction websites.

The multiple afterlives of the nails from Inchtuthil speak to the peculiar status of these ancient objects. While the nail hoard enriches our understanding of metalworking and Roman military practices on the frontier, the individual nails have been treated as expendable material. Still, these objects have sparked the curiosity and interest of the public. Their pristine condition and familiar shape—the basic form of a nail hasn’t changed since antiquity—make the nails strangely contemporary, despite being 2,000 years old. They offer a tangible connection to a specific time and place in Roman history, and since their discovery, are part of the ongoing story of their documentation and global dispersal.

Originally published by The Iris, 01.15.2020, under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.