Advocacy groups, universities, and watchdog scientists are exploring alternative data pools, modeling efforts, and legal pressure for restoration.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

There are moments when the world seems to outrun the records meant to hold it accountable. This is one of them. The recent data from NOAA reveal a country not simply besieged by extreme weather disasters but blindsided, as the machinery designed to monitor them begins to break.

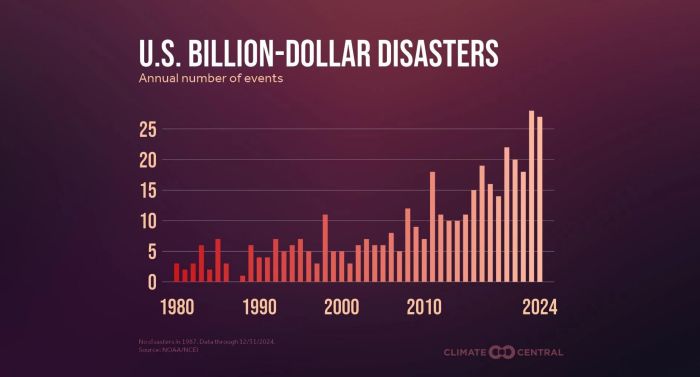

The figures are stark. From a trickle of catastrophic events in the 1980s, barely three per year on average, the U.S. has arrived at a deluge. In 2023, a staggering 28 individual climate or weather disasters crossed the billion-dollar losses threshold. In 2024, that number barely budged downward, counting 27. Over the 45-year stretch from 1980 to 2024, the U.S. tallied 403 such events, collectively costing more than three trillion dollars in today’s economy, and claiming nearly 17,000 lives. These losses have not just accelerated; they have become relentless.

A Surge That Won’t Be Forgotten

Knowing there have been more disasters is one thing; feeling what that means is something else entirely. Wildfires that reshape landscapes, floods that redraw city maps, storms that gut homes with unfathomable force; these are not lines on a chart. For insurance companies, local governments, homeowners, and ironically even those who deny climate warnings, this surge translates into real millions pouring out in reconstruction, relief, and adaptation.

A recent op-ed capturing public sentiment pointed out that every rebuffed alarm becomes painfully real the next time the furnace of extreme weather turns up the heat. For communities already stretched thin, these disasters compound vulnerability, while legislators struggle to keep policy ahead of the crisis.

A Broken Watchtower

Even as losses mount, the tools keeping tabs on this mounting threat are being dismantled. NOAA has announced it will cease updating its flagship database on billion-dollar disasters, creating a rupture in the very data chain scientists rely on. Without ongoing records, preparing for the next catastrophe becomes a guess at best.

Senator Adam Schiff has publicly condemned the decision. With urgency, he warned that suppressing this data suits an agenda that prefers ignorance over planning. He noted the irony, and the danger, of losing sight of disasters as they unfold, while hurricane season looms and key forecasting positions remain empty.

Behind the Numbers

Part of the increase in disaster costs may be traced to deeper population density, development in vulnerable zones, and more expensive infrastructure. But the tight correlation between rising disaster frequency and global warming is too clear to ignore. The Fifth National Climate Assessment leans on NOAA data to assert that climate change is a future threat; it is here and costly in every sense: economic, environmental, human.

When one statistic said that the U.S. now averages one billion-dollar disaster every three weeks, up from one every four months in the 1980s, the numbers snapped their silence into a sharp indictment.

What Could Be Lost

Without the database, living memory (local news coverage, state records, scattered archives) becomes our only fallback. But memory is fragile, especially in places battered by repeated crises. The cost of forgetting is measured not just in dollars but in broken trust, unprepared communities, and slow reactions when icebergs arise where ice was meant to be.

Even more worrisome: removing a central record erodes public discourse. Without evidence, arguments about frequency or severity of climate disasters drift into contestation rather than action.

What Comes Next

There are efforts to bridge the gap. Advocacy groups, universities, and watchdog scientists are exploring alternative data pools, modeling efforts, and legal pressure for restoration. Congress may yet act, but not before the next storm, flood, or fire delivers its lesson firsthand, whether we wanted it or not. And through that, it is worth remembering that data is not a luxury; it is the infrastructure of foresight. Where it breaks, human systems too may falter.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.11.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.