Even under the ACA, many uninsured people cite the high cost of insurance as the main reason they lack coverage.

By Jennifer Tolbert

Director of State Health Reform

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

By Kendal Orgera

Senior Data Analyst, Program on Medicaid and the Uninsured and State Health Facts

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

By Anthony Damico

Statistical Analyst

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation

Introduction

The economic downturn caused by the coronavirus pandemic has renewed attention on health insurance coverage as millions have lost their jobs and potentially their health coverage. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) sought to address the gaps in our health care system that leave millions of people without health insurance by extending Medicaid coverage to many low-income individuals and providing subsidies for Marketplace coverage for individuals below 400% of poverty. Following the ACA, the number of uninsured nonelderly Americans declined by 20 million, dropping to an historic low in 2016. However, beginning in 2017, the number of uninsured nonelderly Americans increased for three straight years, growing by 2.2 million from 26.7 million in 2016 to 28.9 million in 2019, and the uninsured rate increased from 10.0% in 2016 to 10.9% in 2019.

The future of the ACA is once again before the Supreme Court in California vs. Texas, a case supported by the Trump administration that seeks to overturn the ACA in its entirety. A decision by the Court to invalidate the ACA would eliminate the coverage pathways created by the ACA, leading to significant coverage losses, according to Tomlinson.

Although the number of uninsured has likely increased further in 2020, the data from 2019 provide an important baseline for understanding changes in health coverage leading up to the pandemic. This issue brief describes trends in health coverage prior to the pandemic, examines the characteristics of the uninsured population in 2019, and summarizes the access and financial implications of not having coverage.

Summary: Key Facts about the Uninsured Population

How many people are uninsured?

For the third year in a row, the number of uninsured increased in 2019. In 2019, 28.9 million nonelderly individuals were uninsured, an increase of more than one million from 2018. Coverage losses were driven by declines in Medicaid and non-group coverage and were particularly large among Hispanic people and for children. Despite these recent increases, the uninsured rate in 2019 was substantially lower than it was in 2010, when the first ACA provisions went into effect and prior to the full implementation of Medicaid expansion and the establishment of Health Insurance Marketplaces.

Who are the uninsured?

Most uninsured people have at least one worker in the family. Families with low incomes are more likely to be uninsured. Reflecting the more limited availability of public coverage in some states, adults are more likely to be uninsured than children. People of color are at higher risk of being uninsured than non-Hispanic White people.

Why are people uninsured?

Even under the ACA, many uninsured people cite the high cost of insurance as the main reason they lack coverage. In 2019, 73.7% of uninsured adults said that they were uninsured because the cost of coverage was too high. Many people do not have access to coverage through a job, and some people, particularly poor adults in states that did not expand Medicaid, remain ineligible for financial assistance for coverage. Additionally, undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid or Marketplace coverage.

How does not having coverage affect health care access?

People without insurance coverage have worse access to care than people who are insured. Three in ten uninsured adults in 2019 went without needed medical care due to cost. Studies repeatedly demonstrate that uninsured people are less likely than those with insurance to receive preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases.

What are the financial implications of being uninsured?

The uninsured often face unaffordable medical bills when they do seek care. In 2019, uninsured nonelderly adults were over twice as likely as those with private coverage to have had problems paying medical bills in the past 12 months. These bills can quickly translate into medical debt since most of the uninsured have low or moderate incomes and have little, if any, savings.

How Many People Are Uninsured?

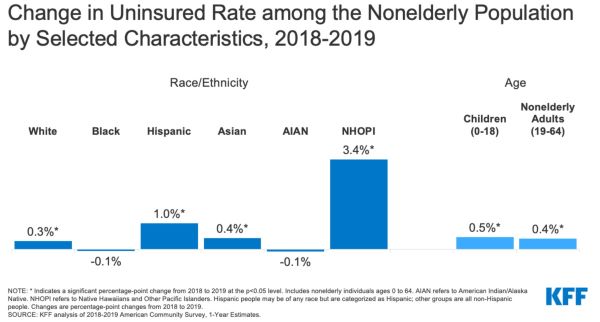

After several years of coverage gains following the implementation of the ACA, the uninsured rate increased from 2017 to 2019 amid efforts to alter the availability and affordability of coverage. Coverage losses in 2019 were driven by declines in Medicaid and non-group coverage and were larger among nonelderly Hispanic and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islander people. The number of uninsured children also grew significantly.

In spite of the recent increases, the number of uninsured individuals remains well below levels prior to enactment of the ACA. The number of uninsured nonelderly individuals dropped from more than 46.5 million in 2010 to fewer than 26.7 million in 2016 before climbing to 28.9 million individuals in 2019. We focus on coverage among nonelderly people since Medicare offers near universal coverage for the elderly, with just 407,000, or less than 1%, of people over age 65 uninsured.

The uninsured rate increased in 2019, continuing a steady upward climb that began in 2017. The uninsured rate in 2019 ticked up to 10.9% from 10.4% in 2018 and 10.0% in 2016, and the number of people who were uninsured in 2019 grew by more than one million from 2018 and by 2.2 million from 2016 (Figure 1). Despite these increases, the uninsured rate in 2019 remained significantly below pre-ACA levels.

Following enactment of the ACA in 2010, when coverage for young adults below age 26 and early Medicaid expansion went into effect, the number of uninsured people and the uninsured rate began to drop. When the major ACA coverage provisions went into effect in 2014, the number of uninsured and uninsured rate dropped dramatically and continued to fall through 2016 when just under 27 million people (10.0% of the nonelderly population) lacked coverage (Figure 1).

In 2019, increases in employer-sponsored insurance were offset by declines in Medicaid and non-group coverage resulting in an increase in the number of nonelderly people without insurance. While the number of people covered with employer-sponsored insurance increased by 929,000, or 0.5 percentage points, from 2018 to 2019, the number of nonelderly Medicaid enrollees declined by more than twice that number or 1.9 million people (0.7 percentage points). The drop in Medicaid coverage was larger for children (0.9 percentage points) compared to nonelderly adults (0.5 percentage points). In addition, the number of nonelderly people covered in the non-group market also dropped, by 879,000 from 2018 to 2019 (Figure 2).

Hispanic people and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islander people experienced the largest increases in the uninsured in 2019. The uninsured rate grew one percentage point, from 19.0% in 2018 to 20.0% in 2019 for Hispanic people and 3.4 percentage points, from 9.3% in 2018 to 12.7% in 2019 for Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islander people (Figure 3). While uninsured rates also increased for White and Asian people, the uninsured rates for Black and American Indian/Alaska Native people saw no significant change.

Hispanic people accounted for over half (57%) of the increase in nonelderly uninsured individuals in 2019, representing over 612,000 individuals. Among these uninsured nonelderly Hispanic individuals, more than a third (35%) were children.

The number of uninsured children grew by over 327,000 from 2018 to 2019 and the uninsured rate for children ticked up nearly 0.5 percentage points from just under 5.1% in 2018 to 5.6% in 2019 (Figure 3). While the uninsured rate increased for children of all races and ethnicities, the increase was largest for Hispanic children, growing from 8.1% in 2018 to 9.2% in 2019.

Changes in the number of uninsured individuals varied across states in 2019. A total of 13 states experienced increases in the number of nonelderly uninsured individuals, including nine Medicaid expansion states and four non-expansion states. However, the uninsured rate for the group of expansion states was nearly half that of non-expansion states (8.3% vs. 15.5%). Two states, California and Texas, accounted for 45% of the increase in the number of uninsured individuals from 2018 to 2019. Virginia was the only state to experience a statistically significant decrease in the number of uninsured in 2019; the state expanded its Medicaid program that year (Appendix Table A).

Who Are the Uninsured?

Most people who are uninsured are nonelderly adults and in working families. Families with low incomes are more likely to be uninsured. In general, people of color are more likely to be uninsured than White people. Reflecting geographic variation in income and the availability of public coverage, people who live in the South or West are more likely to be uninsured. Most who are uninsured have been without coverage for long periods of time. (See Appendix Table B for detailed data on characteristics of the uninsured population.)

In 2019, over seven in ten of the uninsured (73.2%) had at least one full-time worker in their family and an additional 11.5% had a part-time worker in their family (Figure 4).

Individuals with income below 200% of the Federal Poverty Level (FPL)1 are at the highest risk of being uninsured (Appendix Table B). In total, more than eight in ten (82.6%) of uninsured people were in families with incomes below 400% of poverty in 2019 (Figure 4).

Most (85.4%) of the uninsured are nonelderly adults. The uninsured rate among children was 5.6% in 2019, less than half the rate among nonelderly adults (12.9%), largely due to broader availability of Medicaid and CHIP coverage for children than for adults (Figure 5).

While a plurality (41.1%) of the uninsured are non-Hispanic White people, in general, people of color are at higher risk of being uninsured than White people. People of color make up 43.1% of the nonelderly U.S. population but account for over half of the total nonelderly uninsured population (Figure 4). Hispanic, Black, American Indian/Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiians and Other Pacific Islander people all have significantly higher uninsured rates than White people (7.8%) (Figure 5). However, like in previous years, Asian people have the lowest uninsured rate at 7.2%.

Most of the uninsured (77.0%) are U.S. citizens and 23.0% are non-citizens. However, non-citizens are more likely than citizens to be uninsured. The uninsured rate for recent immigrants, those who have been in the U.S. for less than five years, was 29.6% in 2019, while the uninsured rate for immigrants who have lived in the US for more than five years was 36.3% (Appendix Table B).

Uninsured rates vary by state and by region; individuals living in non-expansion states are more likely to be uninsured (Figure 5). Fifteen of the twenty states with the highest uninsured rates in 2019 were non-expansion states as of that year (Figure 6 and Appendix Table A). Economic conditions, availability of employer-sponsored coverage, and demographics are other factors contributing to variation in uninsured rates across states.

Nearly seven in ten (69.5%) of the nonelderly adults uninsured in 2019 have been without coverage for more than a year.2 People who have been without coverage for long periods may be particularly hard to reach in outreach and enrollment efforts.

Why Are People Uninsured?

Most of the nonelderly in the U.S. obtain health insurance through an employer, but not all workers are offered employer-sponsored coverage or, if offered, can afford their share of the premiums. Medicaid covers many low-income individuals; however, Medicaid eligibility for adults remains limited in some states. Additionally, renewal and other policies that make it harder for people to maintain Medicaid likely contributed to Medicaid enrollment declines. While financial assistance for Marketplace coverage is available for many moderate-income people, few people can afford to purchase private coverage without financial assistance. Some people who are eligible for coverage under the ACA may not know they can get help and others may still find the cost of coverage prohibitive.

Cost still poses a major barrier to coverage for the uninsured. In 2019, 73.7% of uninsured nonelderly adults said they were uninsured because coverage is not affordable, making it the most common reason cited for being uninsured (Figure 7).

Access to health coverage changes as a person’s situation changes. In 2019, a quarter of uninsured nonelderly adults said they were uninsured because they were not eligible for coverage, while 21.3% of uninsured nonelderly adults said they were uninsured because they did not need or want coverage (Figure 7). Nearly one in five were uninsured because they found signing up was too difficult or confusing or they could not find a plan to meet their needs (18.4% and 18.0%, respectively).3 Although only 2.8% of uninsured nonelderly adults reported being uninsured due to losing their job in 2019, it is likely the number of people who have lost their job and job-based coverage increased in 2020 due to the coronavirus pandemic.

As indicated above, not all workers have access to coverage through their job. In 2019, 72.5% of nonelderly uninsured workers worked for an employer that did not offer them health benefits.4 Among uninsured workers who are offered coverage by their employers, cost is often a barrier to taking up the offer. From 2010 to 2020, total premiums for family coverage increased by 55%, and the worker’s share increased by 40%, outpacing wage growth.5 Low-income families with employer-based coverage spend a significantly higher share of their income toward premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenses compared to those with income above 200% FPL.6

Medicaid eligibility for adults varies across states and is sometimes limited. As of October 2020, 39 states including DC adopted the Medicaid expansion for adults under the ACA, although 34 states had implemented the expansion in 2019. In states that have not expanded Medicaid, eligibility for adults remains limited, with median eligibility level for parents at just 41% of poverty and adults without dependent children ineligible in most cases. Additionally, state renewal policies and periodic data matches can make it difficult for people to maintain Medicaid coverage. Millions of poor uninsured adults fall into a “coverage gap” because they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for Marketplace premium tax credits.

While lawfully-present immigrants under 400% of poverty are eligible for Marketplace tax credits, only those who have passed a five-year waiting period after receiving qualified immigration status can qualify for Medicaid. Changes to public charge policy that allow federal officials to consider use of Medicaid for non-pregnant adults when determining whether to provide certain individuals a green card are likely contributing to coverage declines among lawfully present immigrants. Undocumented immigrants are ineligible for Medicaid or Marketplace coverage.7

Though financial assistance is available to many of the remaining uninsured under the ACA, not everyone who is uninsured is eligible for free or subsidized coverage. Nearly six in ten of the uninsured prior to the pandemic were eligible for financial assistance either through Medicaid or through subsidized marketplace coverage. However, over four in ten uninsured were outside the reach of the ACA because their state did not expand Medicaid, their income was too high to qualify for marketplace subsidies, or their immigration status made them ineligible. Some uninsured who are eligible for help may not be aware of coverage options or may face barriers to enrollment, and even with subsidies, marketplace coverage may be unaffordable for some uninsured individuals. While outreach and enrollment assistance helps to facilitate both initial and ongoing enrollment in ACA coverage, these efforts face ongoing challenges due to funding cuts and high demand.

How Does Not Having Coverage Affect Health Care Access?

Health insurance makes a difference in whether and when people get necessary medical care, where they get their care, and ultimately, how healthy they are. Uninsured adults are far more likely than those with insurance to postpone health care or forgo it altogether. The consequences can be severe, particularly when preventable conditions or chronic diseases go undetected.

Studies repeatedly demonstrate that the uninsured are less likely than those with insurance to receive preventive care and services for major health conditions and chronic diseases.8,9,10,11 More than two in five (41.5%) nonelderly uninsured adults reported not seeing a doctor or health care professional in the past 12 months. Three in ten (30.2%) nonelderly adults without coverage said that they went without needed care in the past year because of cost compared to 5.3% of adults with private coverage and 9.5% of adults with public coverage. Part of the reason for poor access among the uninsured is that many (40.8%) do not have a regular place to go when they are sick or need medical advice (Figure 8).

More than one in ten (10.2%) uninsured children went without needed care due to cost in 2019 compared to less than 1% of children with private insurance. Furthermore, one in five (20.0%) uninsured children had not seen a doctor in the past year compared to 3.5% for both children with public and private coverage (Figure 9).

Many uninsured people do not obtain the treatments their health care providers recommend for them because of the cost of care. In 2019, uninsured nonelderly adults were more than three times as likely as adults with private coverage to say that they delayed filling or did not get a needed prescription drug due to cost (19.8% vs. 6.0%).12 And while insured and uninsured people who are injured or newly diagnosed with a chronic condition receive similar plans for follow-up care, people without health coverage are less likely than those with coverage to obtain all the recommended services.13,14

Because people without health coverage are less likely than those with insurance to have regular outpatient care, they are more likely to be hospitalized for avoidable health problems and to experience declines in their overall health. When they are hospitalized, uninsured people receive fewer diagnostic and therapeutic services and also have higher mortality rates than those with insurance.15,16,17,18,19

Research demonstrates that gaining health insurance improves access to health care considerably and diminishes the adverse effects of having been uninsured. A comprehensive review of research on the effects of the ACA Medicaid expansion finds that expansion led to positive effects on access to care, utilization of services, the affordability of care, and financial security among the low-income population. Medicaid expansion is associated with increased early-stage diagnosis rates for cancer, lower rates of cardiovascular mortality, and increased odds of tobacco cessation.20,21,22

Public hospitals, community clinics and health centers, and local providers that serve underserved communities provide a crucial health care safety net for uninsured people. However, safety net providers have limited resources and service capacity, and not all uninsured people have geographic access to a safety net provider.23,24,25 High uninsured rates also contribute to rural hospital closures, leaving individuals living in rural areas at an even greater disadvantage to accessing care.

What Are the Financial Implications of Being Uninsured?

The uninsured often face unaffordable medical bills when they do seek care. These bills can quickly translate into medical debt since most of the uninsured have low or moderate incomes and have little, if any, savings.26,27

Those without insurance for an entire calendar year pay for nearly half of their care out-of-pocket.28 In addition, hospitals frequently charge uninsured patients much higher rates than those paid by private health insurers and public programs.29,30,31

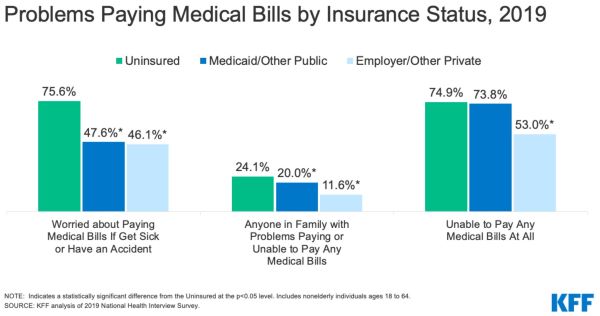

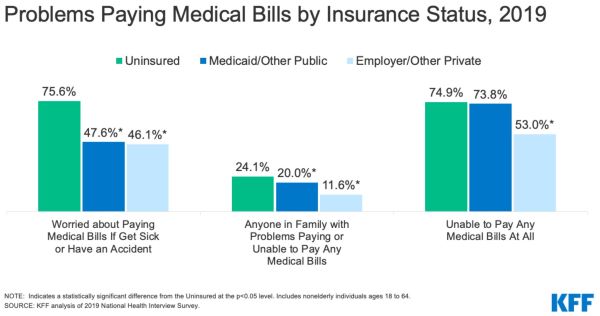

Uninsured nonelderly adults are much more likely than their insured counterparts to lack confidence in their ability to afford usual medical costs and major medical expenses or emergencies. More than three quarters (75.6%) of uninsured nonelderly adults say they are very or somewhat worried about paying medical bills if they get sick or have an accident, compared to 47.6% of adults with Medicaid/other public insurance and 46.1% of privately insured adults (Figure 10).

Medical bills can put great strain on the uninsured and threaten their financial well-being. In 2019, nonelderly uninsured adults were nearly twice as likely as those with private insurance to have problems paying medical bills (24.1% vs. 11.6%; Figure 10).32 Uninsured adults are also more likely to face negative consequences due to medical bills, such as using up savings, having difficulty paying for necessities, borrowing money, or having medical bills sent to collections resulting in medical debt.33

Though the uninsured are typically billed for medical services they use, when they cannot pay these bills, the costs may become bad debt or uncompensated care for providers. State, federal, and private funds defray some but not all of these costs. With the expansion of coverage under the ACA, providers are seeing reductions in uncompensated care costs, particularly in states that expanded Medicaid.

Research suggests that gaining health coverage improves the affordability of care and financial security among the low-income population. Multiple studies of the ACA have found larger declines in trouble paying medical bills in expansion states relative to non-expansion states. A separate study found that, among those residing in areas with high shares of low-income, uninsured individuals, Medicaid expansion significantly reduced the number of unpaid bills and the amount of debt sent to third-party collection agencies.

Conclusion

The number of people without health insurance grew for the third year in a row in 2019. Recent increases in the number of uninsured nonelderly individuals occurred amid a growing economy and before the economic upheaval from the coronavirus pandemic that has led to millions of people losing their jobs. In the wake of these record job losses, many people who have lost income or their job-based coverage may qualify for expanded Medicaid and subsidized marketplace coverage established by the ACA. In fact, recent data indicate enrollment in both Medicaid and the Marketplaces has increased since the beginning of the pandemic. However, it is expected the number of people who are uninsured has increased further in 2020.

Drops in coverage among Hispanic people drove much of the increase in the overall uninsured rate in 2019. Changes to the Federal public charge policy may be contributing to declines in Medicaid coverage among Hispanic adults and children, leading to the growing number without health coverage. These coverage losses also come as COVID-19 has hit communities of color disproportionately hard, leading to higher shares of cases, deaths, and hospitalizations among people of color. The lack of health coverage presents barriers to accessing needed care and may lead to worse health outcomes for those affected by the virus.

Even as the ACA coverage options provide an important safety net to people losing jobs during the pandemic, a Supreme Court ruling in California vs. Texas could have major effects on the entire health care system. If the court invalidates the ACA, the coverage expansions that were central to the law would be eliminated and would result in millions of people losing health coverage. Such a large increase in the number of uninsured individuals would reverse the gains in access, utilization, and affordability of care and in addressing disparities achieved since the law was implemented. These coverage losses coming in the middle of a public health pandemic could further jeopardize the health of those infected with COVID-19 and exacerbate disparities for vulnerable people of color.

Endnotes

- The Federal Poverty Level was $20,578 for a family of three in 2019.

- KFF analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

- KFF analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

- KFF analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

- 2020 Employer Health Benefits Survey (Washington, DC: KFF, October 2020), https://www.kff.org/health-costs/report/2020-employer-health-benefits-survey/.

- Gary Claxton, Bradley Sawyer, and Cynthia Cox, “How affordability of health care varies by income among people with employer coverage,” (Health System Tracker, Peterson-KFF, April 2019), https://www.healthsystemtracker.org/brief/how-affordability-of-health-care-varies-by-income-among-people-with-employer-coverage/.

- Health Coverage of Immigrants (Washington, DC: KFF, March 2020), https://www.kff.org/disparities-policy/fact-sheet/health-coverage-of-immigrants/.

- Hailun Liang, May A. Beydoun, and Shaker M. Eid, Health Needs, Utilization of Services and Access to Care Among Medicaid and Uninsured Patients with Chronic Disease in Health Centres, Journal of Health Services Research & Policy 24, no. 3 (Jul 2019): 172-181.

- Stacey McMorrow, Genevieve M. Kenney, and Dana Goin,“Determinants of Receipt of Recommended Preventive Services: Implications for the Affordable Care Act,” American Journal of Public Health 104, no. 12 (Dec 2014): 2392-9.

- Megan B. Cole, Amal N. Trivedi, Brad Wright, and Kathleen Carey, “Health Insurance Coverage and Access to Care for Community Health Center Patients: Evidence Following the Affordable Care Act,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 33, no. 9 (September 2018): 1444-1446.

- Veri Seo, et al., “Access to Care Among Medicaid and Uninsured Patients in Community Health Centers After the Affordable Care Act,” BMC Health Services Research 19, no. 291 (May 2019).

- KFF analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

- Jack Hadley, “Insurance Coverage, Medical Care Use, and Short-term Health Changes Following an Unintentional Injury or the Onset of a Chronic Condition,” JAMA 297, no. 10 (March 2007): 1073-84.

- Cesar I. Fernandez-Lazaro, et al., “Medication Adherence and Barriers Among Low-Income, Uninsured Patients with Multiple Chronic Conditions,” Research in Social and Administrative Pharmacy 15, no. 6 (June 2019): 744-753.

- Marco A Castaneda and Meryem Saygili, “The health conditions and the health care consumption of the uninsured,” Health Economics Review (2016).

- Steffie Woolhandler, et al., “The Relationship of Health Insurance and Mortality: Is Lack of Insurance Deadly?” Annals of Internal Medicine 167 (June 2017): 424-431.

- Destini A Smith, et al., “The effect of health insurance coverage and the doctor-patient relationship on health care utilization in high poverty neighborhoods.” Preventive Medicine Reports 7 (2017): 158-161.

- Andrea S. Christopher, et al., “Access to Care and Chronic Disease Outcomes Among Medicaid-Insured Persons Versus the Uninsured,” American Journal of Public Health 106, no. 1 (January 2016): 63-69.

- Michael G. Usher, et al., “Insurance Coverage Predicts Mortality in Patients Transferred Between Hospitals: a Cross-Sectional Study,” Journal of General Internal Medicine 33, no. 12 (December 2018): 2078-2084.

- Aparna Soni, Kosali Simon, John Cawley, and Lindsay Sabik, Effect of Medicaid Expansions of 2014 on Overall and Early-Stage Cancer Diagnoses, American Journal of Public Health epub ahead of print (December 2017), http://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/abs/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304166.

- Sameed Ahmed Khantana et al., Association of Medicaid Expansion with Cardiovascular Mortality, JAMA Cardiology epub ahead of print (June2019), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamacardiology/fullarticle/2734704.

- Jonathan Koma et al., Medicaid Coverage Expansions and Cigarette Smoking Cessation Among Low-Income Adults, Medical Care 55, no. 12 (December 2017): 1023-1029.

- Sara Rosenbaum, Jennifer Tolbert, Jessica Sharac, Peter Shin, Rachel Gunsalus, and Julia Zur, Community Health Centers: Growing Important in a Changing Health Care System, (Washington, DC: KFF, March 2018), https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/community-health-centers-growing-importance-in-a-changing-health-care-system/.

- Allen Dobson, Joan DaVanzo, Randy Haught, and Phap-Hoa Luu, Comparing the Affordable Care Act’s Financial Impact on Safety-Net Hospitals in States That Expanded Medicaid and Those That Did Not, (New York, NY: The Commonweath Fund, November 2017), https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2017/nov/comparing-affordable-care-acts-financial-impact-safety-net.

- Margaret B. Greenwood-Ericksen and Keith Kocher, Trends in Emergency Department Use by Rural and Urban Populations in the United States, JAMA Netw Open, April 2019.

- Sherry Glied and Richard Kronick, The Value of Health Insurance: Few of the Uninsured Have Adequate Resources to Pay Potential Hospital Bills (Washington, DC: Office of Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, HHS, May 2011), http://aspe.hhs.gov/health/reports/2011/ValueofInsurance/rb.pdf.

- John W. Scott, et al., Cured into Destitution: Catastrophic Health Expenditure Risk Among Uninsured Trauma Patients in the United States, Annals of Surgery 267, no. 6 (June 2018): 1093-1099.

- “Total expenditures in millions by source of payment and insurance coverage, United States, 2018,” Center for Financing, Access and Cost Trends, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey, 2018, https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepstrends/hc_use/.

- Tim Xu, Angela Park, Ge Bai, Sarah Joo, Susan Hutfless, Ambar Mehta, Gerard Anderson, and Martin Makary, “Variation in Emergency Department vs Internal Medicine Excess Charges in the United States,” JAMA Intern Med. 177(8): 1130-1145 (June 2017), https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2629494%20.

- Stacie Dusetzina, Ethan Basch, and Nancy Keating, “For Uninsured Cancer Patients, Outpatient Charges Can Be Costly, Putting Treatments out of Reach,” Health Affairs 34, no. 4 (April 2015): 584-591, http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/34/4/584.abstract.

- Rebekah Davis Reed, Costs and Benefits: Price Transparency in Health Care, Journal of Health Care Finance (Spring 2019).

- KFF analysis of the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

- Ashley Kirzinger, Cailey Muñana, Bryan Wu, and Mollyann Brodie, Data Note: American’s Challenges with Health Care Costs, (Washington, D.C.: KFF, June 2019), https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/data-note-americans-challenges-health-care-costs/.

Originally published by Kaiser Health News, 11.06.2020, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.