By Geoffrey Robertson

Founder and Co-Head

Doughty Street Chambers

Introduction

From medieval justice to the trial of Charles I, and the trials of John Lilburne to the Human Rights Act, discover the evolution of one of the most venerated features of Anglo-American law.

Trial by jury is the most venerated and venerable institution of Anglo-American law. Although it dates from 1215, it did not come about as a result of Magna Carta, but rather as the consequence of an order by Pope Innocent III (1161–1216). However, Magna Carta’s iconic reference to ‘the lawful judgment of his peers’ as a precondition for loss of liberty has helped in later centuries to entrench the right to jury trial in our pantheon of liberties.

Medieval Criminal Trials

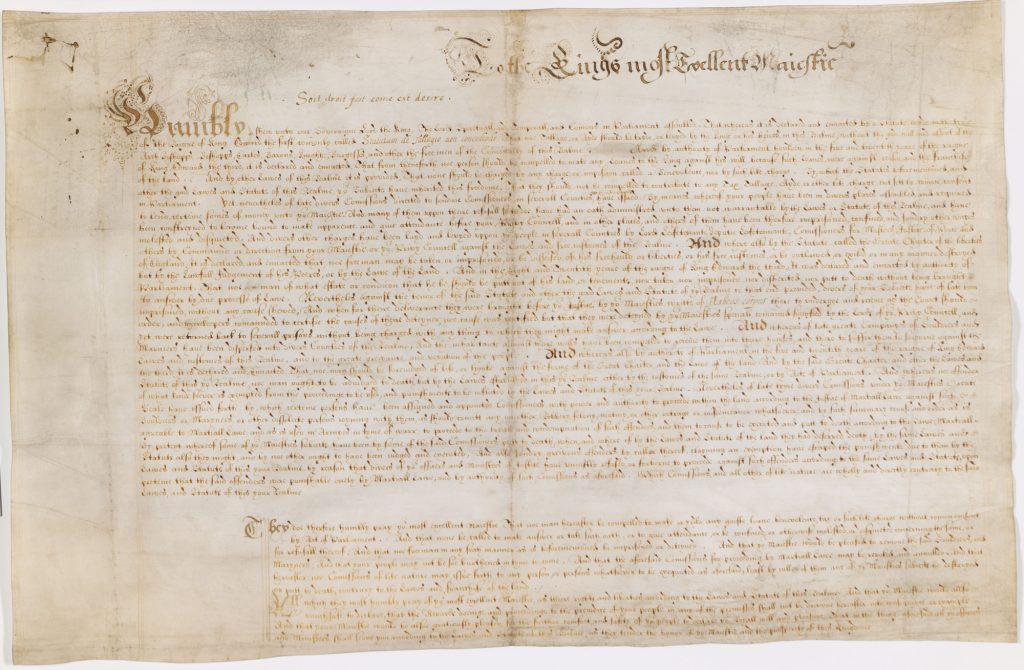

The original clause 39 of the Great Charter of June 1215 reflected a privilege negotiated by the barons to ensure that their disputes with the King – mainly over land – would be settled after advice from men of their own rank and status. Criminal trials at the time took the form of ‘ordeals’ by fire or by water; supervised by the local priest. God was the judge, and he would ensure that the innocent survived – thus, suspects dunked in ponds were declared guilty if they drowned.

In November 1215, Pope Innocent III, perhaps concerned that wrongful convictions were destroying faith in divine providence, forbade clerical participation, and so ‘trial by ordeal’ lost its point. It was replaced by a method of fact-finding used in land disputes and by coroners – the summoning of local men likely to know the circumstances of the crime. In due course, ‘twelve good men and true’ emerged to deliver acceptable verdicts (not until the 20th century were ‘good women and true’ included in their number).

Magna Carta in the Stuart Era

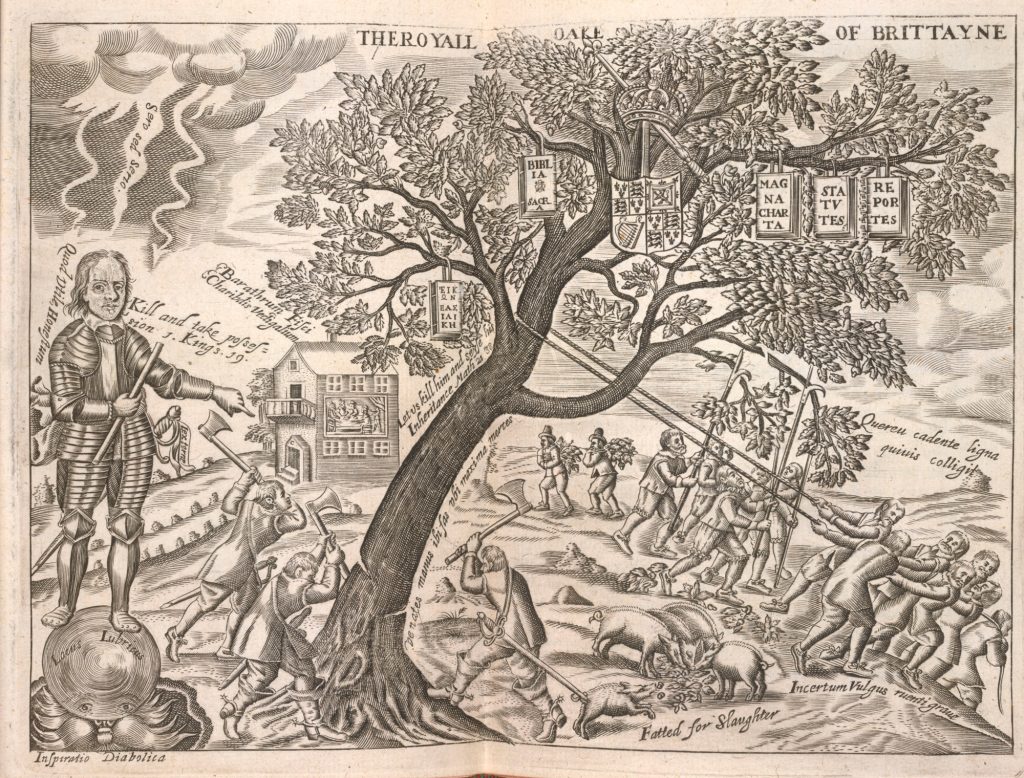

Meanwhile, Magna Carta was sidelined: King John (r. 1199–1216) rejected it only 10 weeks after Runnymede and, although re-issued, the document rarely featured in the courts until Parliament’s struggle against the Stuart kings in the 17th century. The first key date is 1616, when the Chief Justice, Edward Coke (1552–1634), was dismissed by King James I (r. 1603–25) after he had ventured to suggest that the King was not above the law. Coke took himself off to the Inns of Court to write The Institutes of the Lawes of England – a great constitutional text which instructed lawyers and law students that Magna Carta was the basis of the common law, and a precedent for the independence of the law courts from royal control. In 1628 he drafted an updated version of the Charter, called The Petition of Right which parliamentarians demanded that the King (now Charles I) should ratify. He pretended to agree, but then reneged and instead abolished Parliament for 11 years, jailing some of the more outspoken MPs under his executive powers. Magna Carta’s promise of a fair trial was not a right that this King was prepared to grant to anyone: his private court, the Star Chamber, tortured and jailed Puritan preachers as well as one low-born activist, John Lilburne (1614–57).

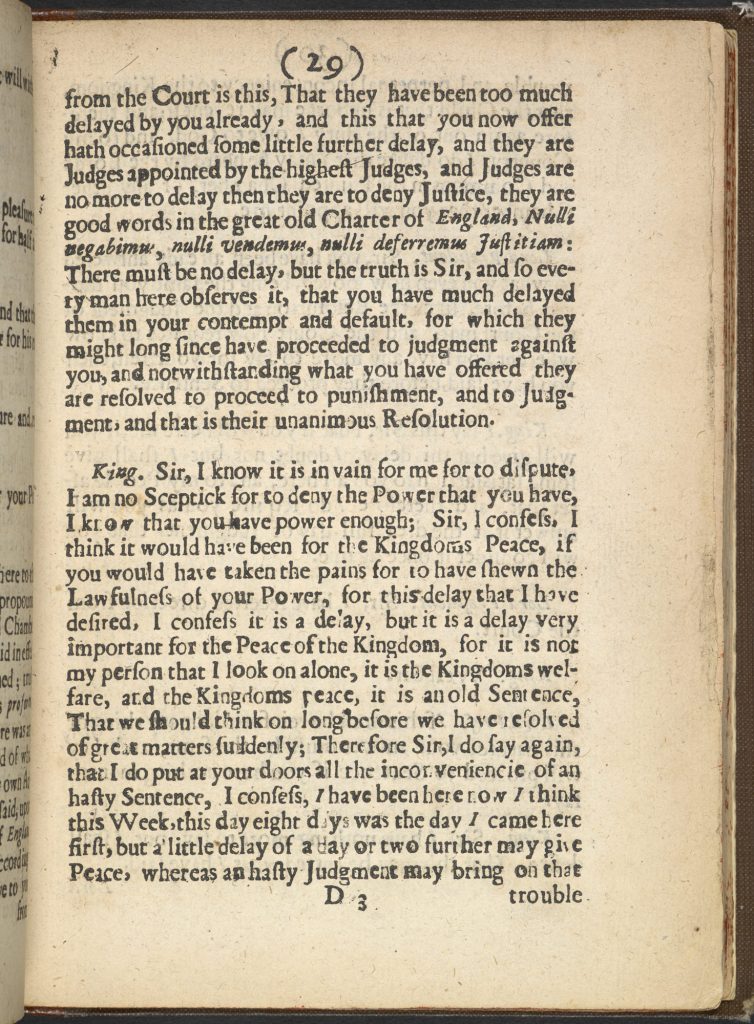

When Charles I (r. 1625–49) was forced to recall Parliament to vote him money for his war against the Scots, the puritan MPs came back with a vengeance, demanding a share in power. The King refused, and took the country to civil war, which between 1642 and 1648 cost the lives of one in ten Englishmen. The victorious Puritan army, led by Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658), wanted Charles, this ‘man of blood’, put on trial, and at this point Magna Carta finally came into its own. The Royalist lawyers accepted that Magna Carta was a basic part of the common law of England, but argued that it required trial by his peers – so the King could not be tried because he had no peers. The Puritans, who had taken their stand on the Charter, summoned a 120-strong jury of the highest officials they could find – generals, Lord Mayors and the like – and then convicted the King of the crime of ‘tyranny’ because he had governed without heed to the Charter’s rights.

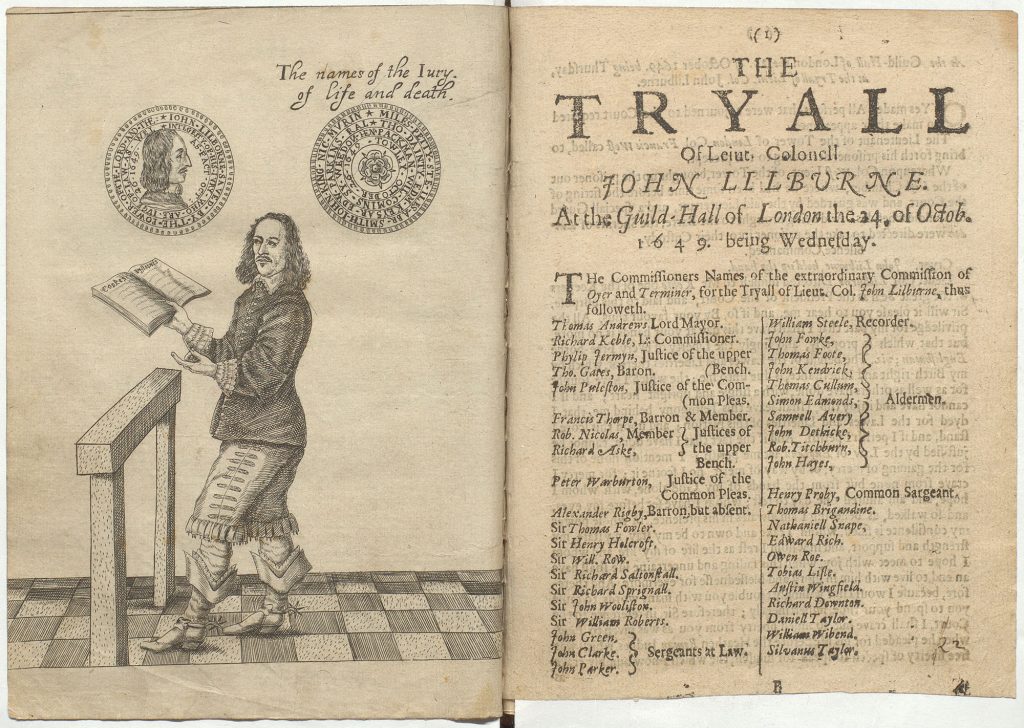

John Lilburne

Trial by jury then had its great champion – John Lilburne (1614–1657) – ‘Freeborn John’ as he was known to his ‘Leveller’ followers. Cromwell twice had him tried for treason and each time Lilburne relied on Coke’s Institutes and Magna Carta to persuade the jury – his peers from London’s tradesmen – to fulfil their historic role and save him from death at the hands of the government which he had criticised. After finding him ‘not guilty of any crime meriting death’, the jurors were threatened by the Lord Chancellor and required to explain their verdict: they refused. Later, in 1670, a jury at the Old Bailey declined to obey the judge’s direction to convict two Quakers, William Penn (1644–1718) and William Mead, despite having them locked up for days without food or fire or chamber-pot. The Court of Common Pleas, who heard the jury’s appeal, was forced to acknowledge that the right to trial by one’s peers, as stated in Magna Carta, entailed a right to acquit, irrespective of the judge’s view that the defendant was guilty.

In other words, clause 39 of Magna Carta had been re-interpreted to assist the struggle against absolutist government. ‘Trial by peers’ no longer referred to an obscure baronial privilege, as it did in 1215. Thanks to Coke and Lilburne and the teachers of the Inns of Court, it was taken in law to mean a right of every defendant prosecuted by the state to ask for acquittal by a body that historian E P Thompson has dubbed ‘the gang of twelve’.

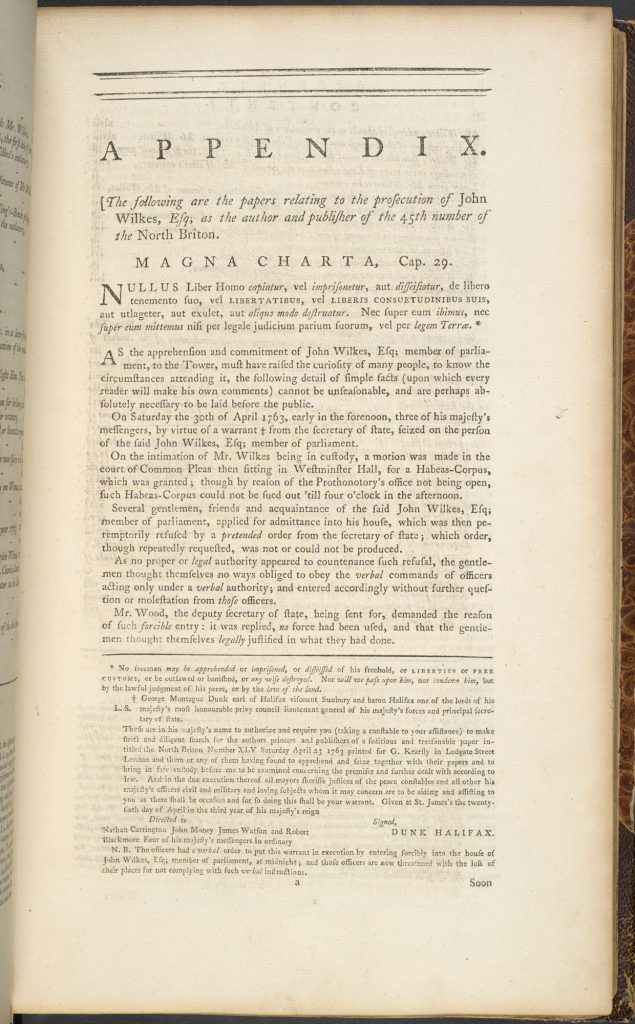

‘Wilkes and Liberty’

The juries in the Old Bailey and in the High Court acted at the end of the 18th century to curb attacks on radicals by King George III (r. 1760–1820) and his ministers. Chants of ‘Wilkes and liberty’ rang loudly from the London mob as they cheered Lord Erskine, a great jury advocate, after he won acquittals in cases brought against the outspoken MP John Wilkes (1725–97) and the publishers of Thomas Paine’s Rights of Man (1791). The government soon responded by ‘vetting’ and bribing jurors in order to obtain convictions in cases of sedition: Jeremy Bentham’s first book, The Elements of the Art of Packing, as applied to Special Juries, etc was an attack on this system of rigging jury trials. At the same time, Charles James Fox (1749–1806) and his supporters in Parliament were quoting Magna Carta in order to ensure that pro-government judges in civil cases did not direct juries to convict. Fox’s Libel Act ensured that the jury, not the judge, would decide whether publications critical of the government could be banned as seditious libels.

By the end of the 19th century, the leading constitutional lawyer, Albert Venn Dicey (1835–1922), could proclaim that freedom of speech was more secure in Britain than anywhere else, simply because the government could not censor without the approval of ‘a jury of shopkeepers’. To Lord Devlin, a distinguished judge in the 1950s, the right to trial by jury was not only guaranteed by Magna Carta, but was ‘the lamp that shows that freedom lives’.

The Problems of Jury Trials

These fine words are, of course, an exaggeration. Juries can go very wrong, especially in ‘terrorist’ cases (see the ‘Birmingham Six’ and the ‘Guildford Four’). They give no reasons for their verdicts, and their deliberations are swathed in unnecessary secrecy. In civil actions they have been virtually abolished – recently (and at the instance of Fox’s descendants, the Liberal Democrats) in libel cases. Jury trials are regarded as too expensive and time-consuming, and free speech is once again at the mercy of judges. In crime, too, the jury has a reduced role. 97% of criminal cases are decided by lay justices or district judges, who may impose prison sentences of up to a year (in cases of contempt of court, heard by judges alone, the sentence may be two years).

Nonetheless, for serious cases, the modern jury – thanks to the re-interpretation of Magna Carta in the 17th century – retains its independence from government and is an important safeguard against oppressive prosecutions. This means that an ordinary, everyday sense of mercy is built into our criminal justice arrangements, in a way that defies strict logic but has won popular acceptance over the centuries. Jury independence means it can ignore the strict letter of the law, and deliver verdicts based on sympathy or humanity and sometimes (given the absurdity of some laws) on common sense.

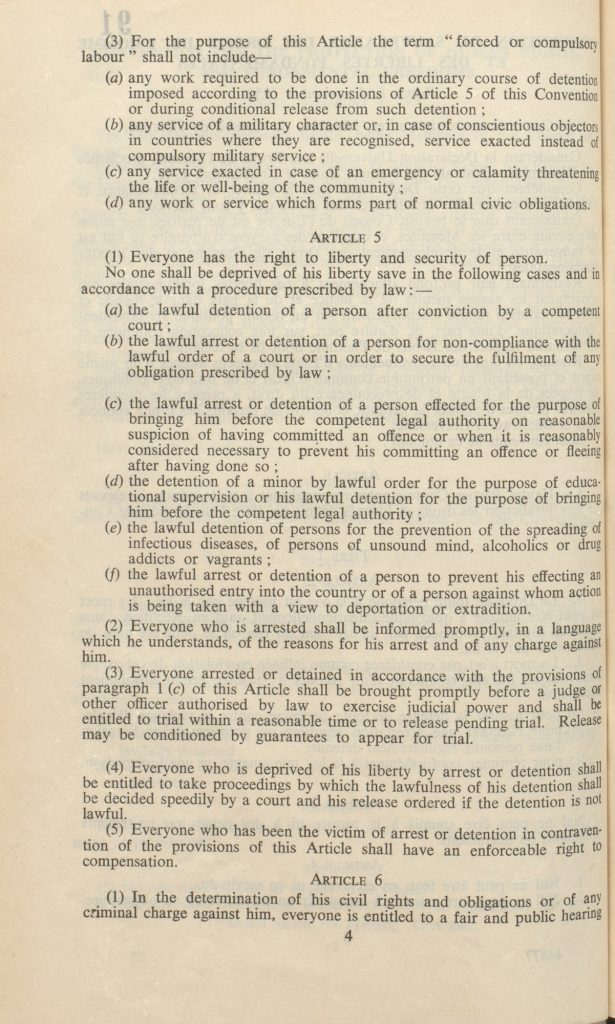

Jury Trial and the Human Rights Act

So why is the basic right to jury trial not included in our Human Rights Act? Because Parliament in 1998 adopted the European Convention on Human Rights, a lowest-common-denominator set of liberties which excluded any mention of juries because Napoleon had abolished them throughout Europe. This has become an important argument in favour of the government’s proposal for a British Bill of Rights. It should have a clause which updates Magna Carta and provides that no person should lose his or her liberty for more than a year without having at least the option of being tried by a jury.

Originally published by the British Library, 03.12.2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.