Because is inseparably linked with Augustus with little known about him, Agrippa’s story will always be told side-by-side with Augustus.

By Jesse Sifuentes

Historian

Introduction

Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa (l. 64/62 – 12 BCE) was Augustus’ (r. 27 BCE – 14 CE) most trusted and unshakably loyal general and his right-hand man in the administration of the city of Rome. Although his name is forever connected with the first Roman emperor and is relegated to the backseat in terms of historical significance, he was one of the most skilled military commanders of Roman warfare, a talented engineer, architect, and administrator.

There is not a wealth of information on Agrippa and because he is inseparably linked with Augustus, Agrippa’s story will always be told side-by-side with Augustus’ (known as Octavian before 27 BCE). He was within a year in age with Octavian, and it is very likely that they were even schooled together and would remain very close throughout their adolescence. Nothing is known about the origin of Agrippa’s family. Agrippa’s gens name – which indicated your particular tribe or clan – Vipsanius was extremely rare, and even Agrippa wanted to cast it aside.

The Ides of March and the Second Triumvirate

Julius Caesar (l. 100-44 BCE) had bequeathed in his will the majority of his property and vast sums of money to Octavian in addition to adopting him as his son. Accepting the content of the will was optional, and doing so carried extraordinary political implications after Caesar’s assassination in 44 BCE – the Ides of March. His acceptance of the will made him enemies with Caesar’s assassins: Marcus Junius Brutus (l. 85-42 BCE) and Gaius Cassius Longinus (l. 85-42 BCE). It also placed Octavian in a contentious relationship with Mark Antony (l. 83-30 BCE), one of Julius Caesar’s best generals who hoped to fill the power void left by Caesar. Octavian formed an impromptu council which included Agrippa and his other close friend, Quintus Salvidienus Rufus. A story, possibly apocryphal, tells of Agrippa convincing Octavian to march on Rome to accept Caesar’s will.

The pro-Caesar faction, Octavian, Antony, and Aemilius Lepidus (l. 89/88 – 13/12 BCE) – a Caesar-supporter – formed the Second Triumvirate in 43 BCE to regulate the Roman Republic and to defeat Caesar’s assassins. Brutus and Cassius were defeated in the Battle of Philippi (42 BCE), and it is very likely that Agrippa fought under the triumvirs there.

Octavian and Antony’s shaky alliance would steadily deteriorate leading to a string of civil wars between the two culminating in the Battle of Actium (31 BCE), which led to the fall of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire. It was during these years that Agrippa made a name for himself, along with Rufus, as an extremely able military commander. Octavian soon discovered that Rufus had opened communications in secret between Antony and was considering switching sides. In 40 BCE, Octavian ordered Rufus to commit suicide for his treachery. This left Agrippa as Octavian’s sole remaining subordinate commander.

The Sicilian War

During these years (44 – 40 BCE), Octavian and Agrippa were busy fighting Caesar’s murderers. This allowed Sextus Pompey (l. 67 – 35 BCE) – son of Pompey the Great and enemy of the Second Triumvirate – to amass a large navy and set up his base on the island of Sicily which was under his total control. There had been peace (Treaty of Misenum) between Pompey and Octavian but hostilities opened up in 38 BCE.

In 39 BCE, Agrippa was the governor of Transalpine Gaul and demonstrated his military skill pacifying unrest among the locals, settling the Ubian tribe in an area to the left of the River Rhine, setting up the first Ubian town which would become the city of Cologne. Agrippa was elected to the consulship in 37 BCE. Agrippa’s consulship was right in the middle of the Second Triumvirate’s 5-year term in which the triumvirs had total power. This meant that the consuls were carefully selected by the triumvirs themselves. Naturally, Agrippa was Octavian’s choice. Lucius Caninius Gallus, a relative of Antony, was the other consul of 37 BCE.

By this time, it was clear that Octavian was not a supremely talented military commander and willingly relied on the skill of subordinates like Agrippa to do the fighting. Octavian faced an emergency and thus called him from Gaul to fight against Pompey who owned the Tyrrhenian Sea with his massive naval fleet and was blockading Italy from its vital grain supply coming from Sicily. This was the start of the Sicilian War in 36 BCE. Agrippa constructed a naval fleet for Octavian. Ancient historian Velleius Paterculus writes:

Marcus Agrippa was charged with constructing the ships, collecting soldiers and rowers, and familiarizing them with naval contests and maneuvers. He was a man of distinguished character, unconquerable by toil, loss of sleep or danger, well disciplined in obedience, but to one man alone, yet eager to command others; in whatever he did he knew no such thing as delay, but with him action went hand in hand with conception. Building an imposing fleet in lakes Avernus and Lucrinus, by daily drills he brought the soldiers and the oarsmen to a thorough knowledge of fighting on land and at sea. (Roman History, 2.79)

Agrippa’s skill was not contained to just military strategy, he also engineered and developed the harpax, a large ballista-like device attached to a large ship that shot a large multi-pronged grappling hook at the end of a rope which would pierce the side of an enemy’s vessel to be boarded.

The plan was to have Octavian sail through the Strait of Messina and land in the eastern Sicilian coast, while Agrippa was to go through the Aeolian Islands and land on the north coast, and Lepidus was to set sail from Africa and land in western Sicily. Of the three, Agrippa was the most successful. Pompey’s ships were lighter and more easily maneuverable, and Agrippa’s ships were heavier, had taller sides, and could withstand more damage. He ran into one of Pompey’s fleets but promptly defeated it at Mylae. Following this naval success, Agrippa and his legions successfully established control in Tyndaris (modern-day Tindari) and surrounding areas.

After some difficulties, Octavian and Lepidus were also able to land in Sicily. Pompey and Octavian then met and agreed to stage a battle between them. They decided that each side would be equally matched with 300 ships apiece, the date would be 3 September, and it would be fought on the northeastern coast in front of the harbor of Naulochus where troops from each side could watch the battle from the shore. The battle took place under these agreed-upon conditions.

Pompey’s fleet was commanded by his trusted admirals, Apollophanes and Demochares. Naturally, Octavian entrusted his fleet to be commanded by Agrippa. Agrippa, using his much larger and stronger ships and the harpax, overwhelmingly defeated Pompey’s fleet losing only three ships in the battle while destroying 28 enemy vessels. Octavian awarded Agrippa with a blue banner and a golden crown for his valor and skill in Roman naval warfare.

The Illyrian War

In 35 BCE, Octavian had a military campaign in the east off the Dalmatian coast (modern-day Croatia) against the Iapodes, a Celtic-Illyrian people. This was the start of the Illyrian War and once again, Agrippa would be Octavian’s right-hand general. Octavian and Agrippa set out from the Adriatic coast and landed in Illyricum. The Romans easily defeated most of the local tribes but then ran into determined resistance when they set siege to the city of Metelum, the Iapodes’ largest and most fortified city.

The Romans put up ramparts and then placed four wooden bridges that stretched from the ramparts to the city walls. When the legionaries ran on the first bridge, it collapsed under the weight. The second and third bridge also fell. At the sight of this, the Roman army was overcome by panic. Augustus jumped down and scolded his legionaries, but they were not stirred to duty by his admonishments so he grabbed a shield and leaped on the bridge himself. Agrippa then followed Octavian’s heroics, and they both crossed the bridge. The soldiers, seeing Octavian and Agrippa’s valiant actions, followed their lead and crossed the bridge, and the city eventually fell.

Agrippa as Aedile

In 33 BCE, Agrippa assumed the office of aedile, a magistracy which oversaw Roman daily life and staging of festivals and entertainment. Aedile was not a mandatory office in the cursus honorum, the political career ladder. It was a rather lowly office for a former consul like Agrippa who had convincingly ousted Sextus Pompey’s fleet in the Sicilian War and fought valiantly in the Illyrian War. Nevertheless, Agrippa carried out his duties as aedile with the same competence he demonstrated on the battlefield.

A new aqueduct, the Aqua Julia – as usual the chief credit for Agrippa’s efforts was tactfully given to his chief – was constructed, and others heavily restored or repaired. It was not just a question of grand building: good access to flowing water was provided throughout Rome, with 700 new cisterns, 500 fountainheads, and 130 water towers. (Goldsworthy, 180)

He also repaired the Marcian aqueduct (aqua Marcia), Rome’s longest aqueduct at over 55 miles. He carried out large-scale civil engineering projects as well as repairing streets and public buildings. Agrippa made sure to clean Rome’s sewage system, organize spectacularly lavish games, and also assist with the social welfare policy that aimed at winning the support of the greater population. Food was distributed to hundreds of thousands of Roman citizens. During public shows, vouchers to redeem money were given out, and clothes and various goods were thrown to the audience. Agrippa would also cast out astrologers and magicians whose practices were considered an affront to traditional Roman religion.

The Battle of Actium

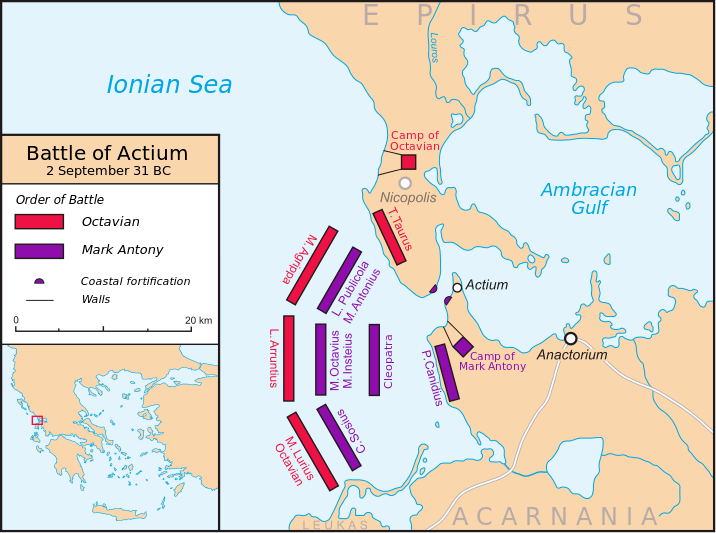

Octavian and Antony’s alliance had rapidly declined, and in 32 BCE, Octavian officially declared war on Antony and his mistress, Cleopatra VII (l. 69-30 BCE). In 31 BCE, their civil war would wrap up at the Battle of Actium in the Gulf of Ambracia off the Greek coast. Agrippa was Octavian’s top general and, naturally, it was he who commenced the attack on Antony’s fleet and had full command of the naval conflict. According to the historian Dr. Adrian Goldsworthy who specializes in the Roman military, it was probably Agrippa who was the mastermind behind the entire strategy and certainly all the most important moments of the battle, leading to the defeat of Antony’s fleet. Even though Antony’s fleet had stronger and larger ships than Octavian’s, he was well aware of the vital experience Octavian’s soldiers had gained in the war against Pompey as well as Agrippa’s skill in naval warfare.

Stormy waters had postponed the battle for days, but the day finally arrived on 2 September 31 BCE. Octavian commanded the right wing of ships, and Agrippa commanded the left wing. Agrippa had used their greater number of ships to envelop Antony’s fleet, and consequently, Sosius – one of Antony’s subordinate commanders – was forced to respond and attack. Antony was forced to bring his entire fleet into battle. Octavian’s ships surrounded Antony’s larger galleys and launched missiles and rammed them, hoping to board the enemy vessels. From the coast, Octavian’s soldiers shot fire arrows and torches onto Antony’s ships. The battle lasted for four hours and Octavian and Agrippa destroyed or captured all of Antony’s ships. The Battle of Actium was certainly the pinnacle of Agrippa’s career as a military general.

Building Projects, Administration, and War in the Empire

After the Battle of Actium, all of Octavian’s enemies were vanquished and he was wholly unopposed in Rome. The post-Actium era was the beginning of the Roman Empire and Octavian – later honored with the name and title of Augustus in 27 BCE – became Rome’s first emperor. Augustus chose Agrippa to be consul in 28 and 27 BCE when he, along with Augustus, would take on the role of censor and carry out the first census (lustrum) of Rome since 71 BCE.

Agrippa then commenced working on three large-scale building projects. In 26 BCE Agrippa finished building the Saepta Julia in honor of Julius Caesar, a building originally planned and started by Caesar which was created for the Tribal Assembly to gather and vote. The voting area was built with marble and adorned with statues and works of high-quality art, and it would have a canopy so the voters could comfortably vote and admire the works of art under the cool shade. Close by were the public Roman baths, the second of Agrippa’s building projects, which included an exercise area and a monument to Neptune – god of the sea – which served as a reminder of the naval victory at Actium.

Lastly, Agrippa began working on one of the most magnificent works of Roman architecture, the Pantheon. The temple was planned as a place for the worship of all the gods – specifically the twelve Olympians because it was based on the Hellenistic example. It would later burn down and was rebuilt by the emperor Hadrian (r. 117-138 CE) who kept Agrippa’s original inscription on the facade of the building. Agrippa also restored and built roads in Rome and the provinces, like his substantial road network in Gaul which improved communication lines and access across the territory.

In 19 BCE, Agrippa was sent to Spain to suppress rebellions by the difficult-to-subdue northwestern Iberian Cantabrians and Asturians. It was not an easy campaign, but ultimately Agrippa proved successful, and the Roman Senate, at the behest of Augustus, voted to award Agrippa a triumph, but he declined the honor. Agrippa very rarely called attention to his own achievements, choosing to attribute all the glory and the peace brought through his military victories to Augustus. Later, in 13 BCE – a year before his death – he returned to the east to quash revolts in Illyria and Pannonia.

Augustus’ Issue of Succession

As Augustus got older, the issue of who he wanted to succeed him as emperor became a pressing matter. Agrippa married Augustus’ only daughter, Julia, in 21 BCE. Augustus openly preferred Agrippa and Julia’s two sons, Gaius and Lucius Caesar. He even adopted them as his own sons, making them his sons and grandsons at the same time. He paraded them about the city, introduced them to public life, and the people of Rome loved them. It was crystal clear who Augustus had in mind to succeed him. But before they came of age, Agrippa was surely in Augustus’ list of possible successors, even if he was not the top candidate.

Agrippa was Augustus’ undisputed second-in-command. In 18 BCE, Augustus even had it arranged for the Senate to grant Agrippa official tribunician power (tribunicia potestas) which allowed him to summon the Senate and People’s Assembly and introduce legislation, as well as greater proconsular power (maius imperium proconsulare) which gave him military precedence over all other subordinate army commanders. The ancient historian, Tacitus, saw tribunician power as the “designation of supreme rank” and described Agrippa as Augustus’ “associate in power” (Annals, 3.56). As a result, if Augustus were to die, only Agrippa held the authority to keep the empire intact and running. When Augustus gave up his consecutive consulships in 23 BCE, it was in “exchange” for these two tremendous powers.

When Augustus fell deathly ill in 23 BCE and was expected by many to pass away, he also gave his signet ring to Agrippa. Agrippa, however, would not outlive Augustus; he died in 12 BCE in Campania during a festival. Augustus gave him a state funeral in Rome where he delivered the eulogy. He then placed Agrippa’s ashes in the Mausoleum of Augustus. Agrippa’s sons, Gaius and Lucius would both suffer untimely and premature deaths, aged 23 and 18 respectively. This left Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE), Augustus’ stepson, as his successor who eventually went on to be the second emperor of Rome.

Agrippa’s Legacy

Agrippa was Augustus’ closest companion, his most skilled subordinate commander, and his right-hand man. He was uncompromisingly loyal and showcased modest selflessness in his shunning of personal recognition and honors for his astounding achievements, choosing to defer the credit and glory to Augustus.

Agrippa’s most important legacy would not be his skill as a military commander, but rather the energy and skill that he dedicated to the betterment of the city with his aqueducts, building projects, road systems, festivals, public art, and general administration of Rome. It would only be after Agrippa’s death that Augustus was forced to create formal administrative roles dedicated to these aspects that Agrippa competently carried out throughout his life.

For the first time in Rome’s history, permanent offices were created to manage waterworks (cura aquarum), another for road building (cura viarum), and for building projects (cura operum publicorum). In the past, these civil engineering tasks were entrusted to magistrates. But now that there were permanent offices, dedicated professionals and experts could oversee and focus on long-term projects who would not be distracted by other responsibilities that a magistrate would have to deal with.

Bibliography

- Appian (Horace White translation). The Foreign Wars. (CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2019).

- Bleicken, J. Augustus. (Penguin UK, 2016).

- Galinsky, K. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Augustus. (Cambridge University Press, 2005).

- Goldsworthy, A. Augustus. (Yale University Press, 2015).

- Paterculus, V. Roman History. (Harvard University Press, 1924).

- Suetonius. The Twelve Caesars. (Penguin Classics, 2007).

- Syme, R. The Roman Revolution. (Oxford University Press, 2002).

- Tacitus. Annals and Histories. (Everyman’s Library, 1783).

- Virgil. The Aeneid. (Hackett Publishing Company, Inc., 2005).

Originally published by the Ancient History Encyclopedia, 01.08.2020, under a Creative Commons: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.