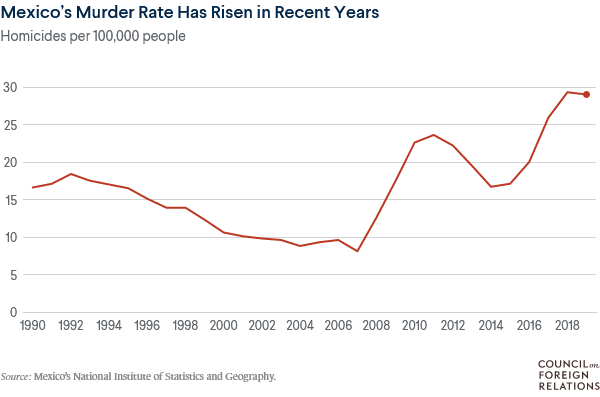

Mexican authorities have been waging a deadly battle against drug cartels for more than a decade, but with limited success. Thousands of Mexicans—including politicians, students, and journalists—die in the conflict every year. The country has seen more than three hundred thousand homicides since 2006, when the government declared war on the cartels.

The United States has partnered closely with its southern neighbor in this fight, providing Mexico with billions of dollars to modernize its security forces, reform its judicial system, and make other investments. Washington has also sought to stem the flow of illegal drugs into the United States by bolstering security along its border.

What drugs do the cartels traffic?

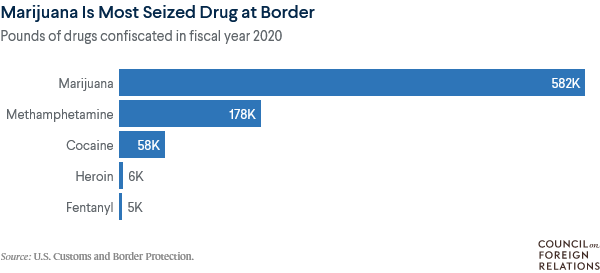

Mexican drug trafficking groups—sometimes referred to as transnational criminal organizations—dominate the import and distribution of cocaine, fentanyl, heroin, marijuana, and methamphetamine in the United States. Mexican suppliers are responsible for most heroin and methamphetamine production, while cocaine is largely produced in Colombia and then transported to the United States by Mexican criminal organizations. Mexico, along with China, is also a leading source of fentanyl, a synthetic opioid many times more potent than heroin. The amount of fentanyl seized by Mexican authorities nearly quintupled between 2019 and 2020.

At the same time, the cartels smuggle vast quantities of marijuana into the United States, even though some U.S. jurisdictions have legalized it. Related AMLO’s ‘Hugs Not Bullets’ Is Failing Mexico by Shannon K. O’Neil Mexican Migration Could Be the First Crisis of 2021 by Shannon K. O’Neil The U.S. Opioid Epidemic by Claire Felter

Which are the largest cartels?

Mexico’s drug cartels are in a constant state of flux. Over the decades, they have grown, splintered, forged new alliances, and battled one another for territory. The cartels that pose the most significant drug trafficking threats [PDF] to the United States, according to the U.S. Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), are:

Sinaloa Cartel. Formerly led by Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman, Sinaloa is one of Mexico’s oldest and most influential drug trafficking groups. With strongholds in the northwest and along Mexico’s Pacific coast, it has a larger international footprint than any of its Mexican rivals. In 2017, Mexican authorities extradited Guzman to the United States, where he is serving a life sentence for multiple drug-related charges.

Jalisco New Generation Cartel. Also known as CJNG, Jalisco splintered from Sinaloa in 2010 and is among Mexico’s swiftest-growing cartels, with operations in more than two-thirds of Mexico’s states. According to the DEA, the “rapid expansion of its drug trafficking activities is characterized by the organization’s willingness to engage in violent confrontations” with authorities and other cartels. U.S. officials link the cartel to more than one-third of the drugs in the United States.

Juarez Cartel. A long-standing rival of Sinaloa, Juarez has its stronghold in the north-central state of Chihuahua, across the border from New Mexico and Texas.

Gulf Cartel. Its base of power is in the northeast, especially the state of Tamaulipas. In the past decade, Gulf has splintered into various factions, diluting its strength as it battles for territory with Los Zetas.

Los Zetas. Originally a paramilitary enforcement arm for the Gulf Cartel, Los Zetas was singled out by the DEA in 2007 as the country’s most “technologically advanced, sophisticated, and violent” group of its kind. It splintered from Gulf in 2010 and held sway over swaths of eastern, central, and southern Mexico. However, it has lost power in recent years and fractured into rival wings.

Beltran-Leyva Organization. The group formed when the Beltran-Leyva brothers split from Sinaloa in 2008. Since then, all four brothers have been arrested or killed, but their loyalists operate throughout Mexico. The organization’s splinter groups have become more autonomous and powerful, maintaining ties to Jalisco, Juarez, and Los Zetas.

What led to the cartels’ growth?

Experts point to both domestic and international forces. In Mexico, the cartels use a portion of their vast profits to pay off judges, police, and politicians. They also coerce officials into cooperating; assassinations of public servants are relatively common.

The cartels flourished during the decades that Mexico was ruled by a single party, the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). Within this centralized political structure, drug trafficking groups cultivated a wide network of corrupt officials through which they were able to gain distribution rights, market access, and protection.

The PRI’s unbroken reign finally ended in 2000 with the election of President Vicente Fox of the National Action Party (PAN). With new politicians in power, cartels ramped up violence against the government in an effort to reestablish their hold [PDF] on the state.

At the international level, Mexican cartels began to take on a much larger role in the late 1980s, after U.S. government agencies broke up Caribbean networks used by Colombian cartels to smuggle cocaine. Mexican gangs eventually shifted from being couriers for Colombian criminal organizations to being wholesalers.

The U.S. government, despite waging a “war on drugs” and conducting other counternarcotics efforts abroad, has made little progress in reducing the demand for illegal drugs. In 2016, Americans spent almost $150 billion on cocaine, heroin, marijuana, and methamphetamine, 50 percent more than in 2010. Meanwhile, growing use of synthetic opioids, including fentanyl, has contributed to a public health crisis.

How are drugs smuggled into the United States?

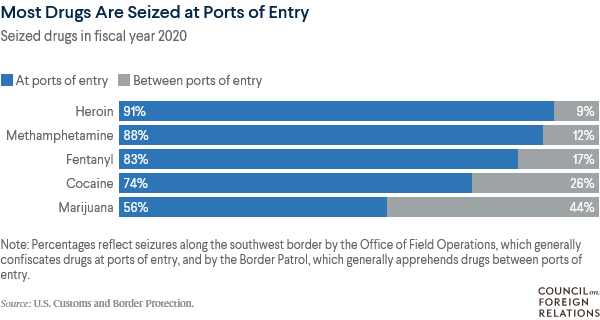

Most of the illicit drugs entering the United States that are seized by authorities are discovered at official ports of entry, of which there are more than three hundred.

Traffickers employ various tactics to evade detection by U.S. authorities at the border. These include hiding or disguising drugs in vehicles, smuggling them into the United States through underground tunnels, and flying them over border barriers using drones or other aircraft. After Mexican traffickers smuggle wholesale shipments of drugs into the United States, local groups and street gangs manage retail-level distribution in cities throughout the country.

What measures has Mexico taken to stem the drug trade?

Recent Mexican administrations have responded to cartels primarily by deploying security forces, often spurring more violence:

Felipe Calderon (2006–2012). President Calderon declared war on the cartels shortly after taking office. Over the course of his six-year term, he deployed tens of thousands of military personnel to supplement and, in many cases, replace local police forces he viewed as corrupt. With U.S. assistance, the Mexican military captured or killed twenty-five of the top thirty-seven drug kingpins in Mexico. The militarized crackdown was a centerpiece of Calderon’s tenure.

However, some critics say Calderon’s decapitation strategy created dozens of smaller, more violent drug gangs. Many also argue that Mexico’s military is ill-prepared to perform police functions. The government registered more than 120,000 homicides [PDF] over the course of Calderon’s term, nearly twice as many as during his predecessor’s time in office. (Experts estimate that between one-third and one-half of the homicides in Mexico are linked to cartels.)

Enrique Pena Nieto (2012–2018). Calderon’s successor said he would focus more on reducing violence against civilians and businesses than on removing the leaders of cartels. Still, President Pena Nieto relied heavily [PDF] on the military, in combination with the federal police, to battle the cartels. He also created a new national police force, or gendarmerie, of several thousand officers.

Homicides declined in the first years of Pena Nieto’s presidency. But 2015 saw an uptick, and by the end of his term, the number of homicides had risen to the highest level in modern Mexican history. Experts attribute this to the continued fallout from the kingpin strategy and territorial feuds between gangs.

Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (2018–present). Shortly after taking office, President Lopez Obrador announced that his government would move away from attempts to apprehend cartel leaders and instead focus on improving security and reducing homicide rates. His “hugs not bullets” approach to organized crime seeks to address the socioeconomic drivers of the problem. His administration launched an anticorruption drive and disrupted cartel finances; it has also proposed decriminalizing drugs and offering amnesty to low-level cartel members.

Though Lopez Obrador has framed his strategy as a novel approach, some experts say his actions—including deploying a new national guard to boost security—echo his predecessors’ tactics. Meanwhile, homicides have hovered around record levels.

What has been the toll on human rights?

Civil liberties groups, journalists, and others have criticized the Mexican government’s war with the cartels for years, accusing the military, police, and cartels of widespread human rights violations, including torture, extrajudicial killings, and forced disappearances. More than sixty-six thousand people have disappeared since 2006, primarily at the hands of criminal organizations such as the cartels, though government forces also play a role. Efforts to find the missing and prosecute those responsible have often been stymied by cartel-related violence, government incompetence and corruption, and other factors.

One of the most chilling examples of these abuses occurred in the southern state of Guerrero in 2014, when more than forty student protesters were abducted and presumably killed, though remains of only two students have been definitively identified. The incident prompted mass demonstrations, with protesters demanding answers about the abductions and expressing their exhaustion with Mexico’s endemic corruption, violence, and other crime. Investigations into the students’ disappearances have purportedly found evidence that authorities, including the police and military, conspired with cartel members in the crimes; the government launched a new inquiry after the students’ families, human rights groups, and independent experts questioned the handling of the previous investigation.

In recent years, vigilante groups known as autodefensas have sought to fill in where security forces have failed to protect communities from criminal groups. They have become a formidable force against the cartels in states including Guerrero and Michoacan. However, some vigilantes have committed rights abuses, including the recruitment of child fighters; allegedly maintained ties to cartels; and even turned to organized crime themselves.

What assistance has the U.S. government provided?

The United States has cooperated with Mexico on security and counternarcotics to varying degrees over several decades. Recent efforts have centered on the Merida Initiative; since Presidents George W. Bush and Calderon launched the partnership [PDF] in 2007, the United States has appropriated more than $3 billion for it.

The Merida Initiative has evolved to reflect the priorities of national leaders. The Bush administration focused heavily on providing Mexico with security-related assistance, including counternarcotics and counterterrorism support. President Barack Obama widened the scope of aid to target fundamental reforms to Mexico’s justice system and to develop crime-prevention programs at the community level, among other efforts.

Originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations, 02.26.2021, under the terms a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.