Russia’s position is much weaker, but Putin remains dangerous.

By Dr. Ronald H. Linden

Professor Emeritus of Political Science

University of Pittsburgh

Introduction

Russia President Vladimir Putin sent a guarded message of congratulations to Donald Trump on inauguration day, but then held a long direct call with his “dear friend,” Chinese leader Xi Jinping.

From Putin’s perspective, this makes sense. Russia gets billions of dollars from energy sales to China and technology from Beijing, but from Washington, until recently, mostly sanctions and suspicion.

Moscow is hoping for a more positive relationship with the current White House occupant, who has made his desire for a “deal” to end the Ukraine war well known.

But talk of exit scenarios from this 3-year-old conflict should not mask the fact that since the invasion began, Putin has overseen one of the worst periods in Russian foreign policy since the end of the Cold War.

Transatlantic Unity

The war in Ukraine has foreclosed on options and blunted Russian action around the world.

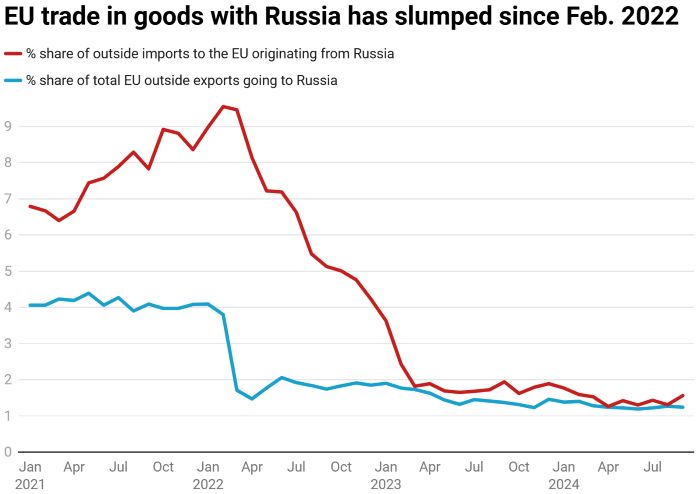

Unlike the annexation of Crimea in 2014, the 2022 invasion produced an unprecedented level of transatlantic unity, including the expansion of NATO and sanctions on Russian trade and finance. In the past year, both the U.S. and the European Union expanded their sanction packages.

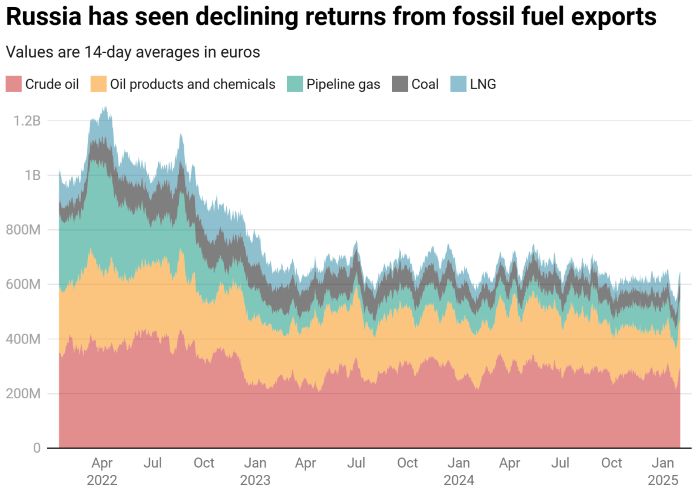

And for the first time, the EU banned the re-export of Russian liquefied natural gas and ended support for a Russian LNG project in the Arctic.

EU-Russian trade, including European imports of energy, has dropped to a fraction of what it was before the war.

The two Nordstrom pipelines, designed to bring Russian gas to Germany without transiting East Europe, lie crippled and unused. Revenues from energy sales are roughly one-half of what they were two years ago.

At the same time, the West has sent billions in military and humanitarian aid to Ukraine, enabling a level of resilience for which Russia was unprepared. Meanwhile, global companies and technical experts and intellectuals have fled Russia in droves.

While Russia has evaded some restrictions with its “shadow fleet” – an aging group of tankers sailing under various administrative and technical evasions – the country’s main savior is now China. Trade between China and Russia has grown by nearly two-thirds since the end of 2021, and the U.S. cites Beijing as the main source of Russia’s “dual use” and other technologies needed to pursue its war.

Since the start of the war in Ukraine, Russia has moved from an energy-for-manufactured-goods trade relationship with the West to one of vassalage with China, as one Russia analyst termed it.

Hosting an October meeting of the BRICS countries – now counting 11 members, including the five original members: Brazil, Russia, India, China and South America – is unlikely to compensate for geopolitical losses elsewhere.

Problems at Home …

The Russian economy is deeply distorted by increased military spending, which represents 40% of the budget and 25% of all spending. The government now needs the equivalent of US$20 billion annually in order to pay for new recruits.

Russian leaders must find a way to keep at least some of the population satisfied, but persistent inflation and reserve currency shortages flowing directly from the war have made this task more difficult.

On the battlefield, the war itself has killed or wounded more than 600,000 Russian soldiers. Operations during 2024 were particularly deadly, producing more than 1,500 Russian casualties a day.

The leader who expected Kyiv’s capitulation in days now finds Russian territory around Kursk occupied, its naval forces in the Black Sea destroyed and withdrawn, and its own generals assassinated in Moscow.

But probably the greatest humiliation is that this putative great power with a population of 144 million must resort to importing North Korean troops to help liberate its own land.

… And in Its Backyard

Moscow’s dedication to the war has affected its ability to influence events elsewhere, even in its own neighborhood.

In the Caucasus, for example, Russia had long sided with Armenia in its running battle with Azerbaijan over boundaries and population after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Moscow has brokered ceasefires at various points. But intermittent attacks and territorial gains for Azerbaijan continued despite the presence of some 2,000 Russian peacekeepers sent to protect the remaining Armenian population in parts of the disputed territory of Nagorno-Karabakh.

In September 2023, Azerbaijan’s forces abruptly took control of the rest of Nagorno-Karabakh. More than 100,000 Armenians fled in the largest ethnic cleansing episode since the end of the Balkan Wars. The peacekeepers did not intervene and later withdrew. The Russian military, absorbed in the bloody campaigns in Ukraine, could not back up or reinforce them.

The Azeris’ diplomatic and economic position has gained in recent years, aided by demand for its gas as a substitute for Russia’s and support from NATO member Turkey.

Feeling betrayed by Russia, the Armenian government has for the first time extended feelers toward the West — which is happy to entertain such overtures.

Losing Influence and Friends

Russia’s loss in the Caucasus has been dwarfed by the damage to its military position and influence in the Middle East. Russia supported the Syrian regime of Bashar al-Assad against the uprisings of the Arab Spring in 2011 and saved it with direct military intervention beginning in 2015.

Yet in December 2024, Assad was unexpectedly swept away by a mélange of rebel groups. The refuge extended to Assad by Moscow was the most it could provide with the war in Ukraine having drained Russia’s capacity to do more.

Russia’s possible withdrawal from the Syrian naval base at Tartus and the airbase at Khmeimim would remove assets that allowed it to cooperate with Iran, its key strategic partner in the region.

More recently, Russia’s reliability as an ally and reputation as an armory has been damaged by Israeli attacks not only on Hezbollah and other Iranian-backed forces in Lebanon and Syria, but on Iran itself.

Russia’s position in Africa would also be damaged by the loss of the Syrian bases, which are key launch points for extending Russian power, and by Moscow’s evident inability to make a difference on the ground across the Sahel region in north-central Africa.

Dirty Tricks, Diminishing Returns

Stalemate in Ukraine and Russian strategic losses in Syria and elsewhere have prompted Moscow to rely increasingly on a variety of other means to try to gain influence.

Disinformation, election meddling and varied threats are not new and are part of Russia’s actions in Ukraine. But recent efforts in East Europe have not been very productive. Massive Russian funding and propaganda in Romania, for example, helped produce a narrow victory for an anti-NATO presidential candidate in December 2024, but the Romanian government moved quickly to expose these actions and the election was annulled.

Nearby Moldova has long been subject to Russian propaganda and threats, especially during recent presidential elections and a referendum on stipulating a “European course” in the constitution. The tiny country moved to reduce its dependency on Russian gas but remains territorially fragmented by the breakaway region of Transnistria that, until recently, provided most of the country’s electricity.

Despite these factors, the results were not what Moscow wanted. In both votes, a European direction was favored by the electorate. When the Transnistrian legislature in February 2024 appealed to Moscow for protection, none was forthcoming.

When Moldova thumbs its nose at you, it’s fair to say your power ranking has fallen.

Wounded but Still Dangerous

Not all recent developments have been negative for Moscow. State control of the economy has allowed for rapid rebuilding of a depleted military and support for its technology industry in the short term. With Chinese help and evasion of sanctions, sufficient machinery and energy allow the war in Ukraine to continue.

And the inauguration of Donald Trump is likely to favor Putin, despite some mixed signals. The U.S. president has threatened tariffs and more sanctions but also disbanded a Biden-era task force aimed a punishing Russian oligarchs who help Russia evade sanctions. In the White House now is someone who has openly admired Putin, expressed skepticism over U.S. support for Ukraine and rushed to bully America’s closest allies in Latin America, Canada and Europe.

Most importantly, Trump’s eagerness to make good on his pledge to end the war may provide the Russian leader with a deal he can call a “victory.”

The shrinking of Russia’s world has not necessarily made Russia less dangerous; it could be quite the opposite. Some Kremlin watchers argue that a more economically isolated Russia is less vulnerable to American economic pressure. A retreating Russia and an embattled Putin could also opt for even more reckless threats and actions – for example, on nuclear weapons – especially if reversing course in Ukraine would jeopardize his position. It is, after all, Putin’s war.

All observers would be wise to note that the famous dictum “Russia is never as strong as she looks … nor as weak as she looks” has been ominously rephrased by Putin himself: “Russia was never so strong as it wants to be and never so weak as it is thought to be.”

Originally published by The Conversation, 02.10.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.