The more China puts pressure on North Korea, the more likely the latter would resist.

By Dr. Weiqi Zhang / 02.12.2018

Assistant Professor of East Asian Politics

Suffolk University

Abstract

North Korea has defied the international community on its nuclear program despite diplomatic and economic pressure. Why has the country been willing and able to defy and resist the international community? What should we do about it? Many stress China’s ties with North Korea and believe that the question of whether China is willing to use its leverage on North Korea is the key to the solution to the Korean nuclear issue. This paper draws from international relations theories and the history of China–North Korea relations to analyze North Korean foreign policy strategy. Two arguments are made, namely: first, that North Korea does not view its relationship with China as highly as many would think; and, second, that China’s role in North Korea’s strategic planning is not significant enough to change its behavior. Therefore, it is argued, asking China to use its leverage on North Korea would not solve the Korean nuclear crisis. On the contrary, the more China puts pressure on North Korea, the more likely the latter would resist. A possible way ahead in dealing with the Korean nuclear issue is proposed.

Introduction

I visited North Korea in May 2016. The 5-day trip gave me some interesting insight into the North Korea–China relationship. For instance, my North Korean guides never mentioned the “friendship” between North Korea and China during the trip even when we visited the “Friendship tower”, a monument to the Chinese Voluntary Army who died during the Korean War. Furthermore, they told me that China had been rarely mentioned in the North Korean media and that when it was mentioned it was not referred to as an ally or friend. When I asked the guides about their opinion on China’s vote for the economic sanction against North Korea in the UN Security Council, they said that China had the right to do anything to pursue its national interest and that North Korea by the same token should do the same.

To me, such insights shed light on the North Korea–China relationship and the Korean nuclear issue. Despite increasingly heavier international diplomatic and economic pressure, North Korea has defied the international community by conducting more frequent nuclear and missile tests (Table 1). Many believe that the North Korean leaders are irrational and unpredictable (Zahn, 2017). Others believe that North Korea’s defiance is attributable to China’s protection and that China should faithfully enforce the international economic sanctions and put greater pressure on North Korea to change its behavior (Dyer, 2016; Office of the Press Secretary, 2014).

China has put increasingly heavier pressure on North Korea, but its pressure has had little impact on the latter’s behavior. For instance, according to the International Trade Center, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, after North Korea’s first nuclear test in 2006 China cut its cereal exports to North Korea by 66% (International Trade Centre, 2017). When North Korea conducted the second nuclear test in 2009, China reduced its fuel exports by 44%. In 2013 China slashed fuels exports and cereal exports to North Korea by 81 and 89%, respectively after the latter conducted a third nuclear test. More recently, in response to the latest North Korean nuclear test and missile tests, China banned exports of petroleum to and imports of textile from North Korea and ordered all North Korean business in China to be closed (Clover et al. 2017; Doubek, 2017). During the same time period, as Table 1 shows, North Korea increased the frequencies of the tests. If China’s pressure is really a key to changing North Korea’s behavior, then why has the situation worsened with greater Chinese pressure? How to explain North Korea’s behavior?

North Korea’s Foreign Policy Strategies

International relations theories indicate that a state is rational and seeks to maximize its chance of survival in an anarchic international system. For a small power whose capability is insufficient to guarantee security, it is particularly concerned about being abused by great powers (Waltz, 1979). The reaction of a small power to big powers depends on its perception of threat, which is affected by other states’ capability and intention (Jervis, 1976; Kang, 2003; Walt, 1987).

A state feels less threatened by its ally than by an adversary. Since the state expects greater future benefits from its ally, it is receptive to the ally’s requests to change policies even if doing so would incur short-term costs. On the contrary, if a state’s adversary requests it to change policies, the state would not grant the request even if it could benefit from doing so. The reason is that the state expects future long-term conflicts with the adversary and greater overall costs. Moreover, abiding by the adversary’s request not only implies the state’s weakness. In the case of North Korea, the US and its allies in Northeast Asia have been officially viewed by North Korea as the biggest threat because they have the capabilities and clear intention to threaten the survival of the North Korean regime.

To cope with an external threat, a state has the following options: bandwagoning with the threatening state, buck-passing (free-riding other states’ effort to balance against the threat), and balancing against the threat. Among these options, a small state is the most likely to bandwagon with the threat than balancing against it (Powell, 1999; Schroeder, 1994; Schweller, 1994; Walt, 1985). However, bandwagoning is not a viable option for North Korea. Since North Korea views the US as an imperialist power that has illegally occupied southern Korea and brought economic hardship and insecurity to the north, bandwagoning with the US would undermine the legitimacy of the North Korean government. Buck-passing is unavailable for North Korea either because this strategy requires multiple status quo powers in the region to be able and willing to balance against the threat on behalf of the small state. As no other Asian country is seeking open, direct conflict with the US, the post-Cold War Northeast Asia geopolitics does not have the condition for North Korea to “pass the buck.”

Balancing, hence, is the only feasible strategy for North Korea. A state can balance against a threat internally (improve its own military capability) or externally (form flexible alliances). Internally, North Korea started its nuclear program in the 1950s with the assistance of the Soviet Union to counter the US nuclear threat from within South Korea (Kristensen and Robert, 2017). The choice of nuclear weapon is based on the idea that it is a more cost-effective defensive weapon than conventional ones (Schwartz, 2008; Waltz, 1990). With technological development, the cost of developing and deploying nuclear weapons has become increasingly more affordable to states (Erickson, 2001). Although it is pointed out that nuclear weapons could incur high long-term social costs, these costs could be significantly discounted in the short term by a state that is under immediate security threat (Epstein, 1977).

North Korea’s nuclear weaponization process was slow during the Cold War due to the Soviet constraint. Nonetheless, the collapse of the Soviet Union exposed North Korea to external threats and motivated Kim Jong-Il to accelerate the nuclear program under the “military first” policy, which attracted the US attention. Even though the two countries mitigated the crisis with the Framework Agreement in 1994, the deal fell apart when the US failed to provide North Korea with two light-water reactors and the latter responded by resuming its nuclear programs. After witnessing the fate of Iraq and Libya, North Korean leaders firmly believe that compromising on nuclear weapon for the sake of economic or diplomatic gains would not only undermine its security but also makes North Korean regime look weak and thus vulnerable in the future negotiations (KCNA, 2017a).

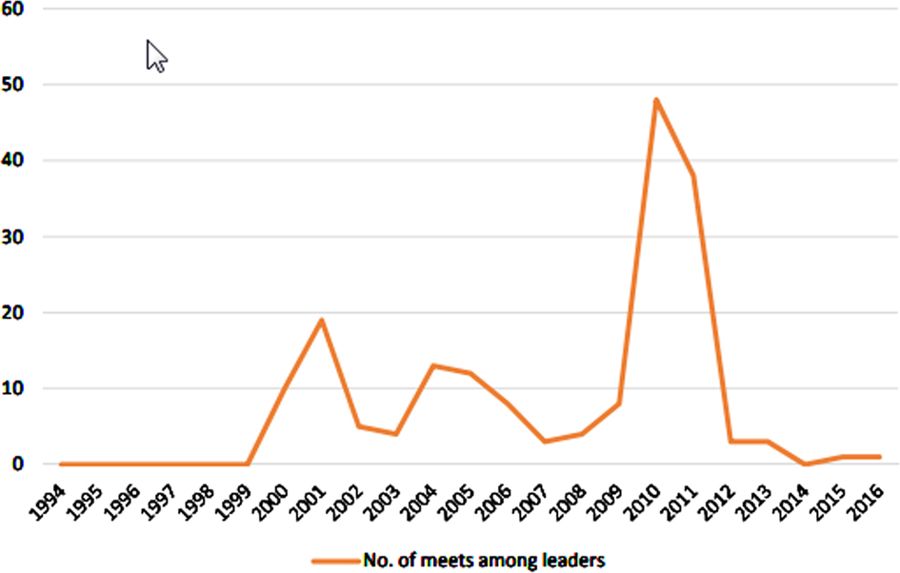

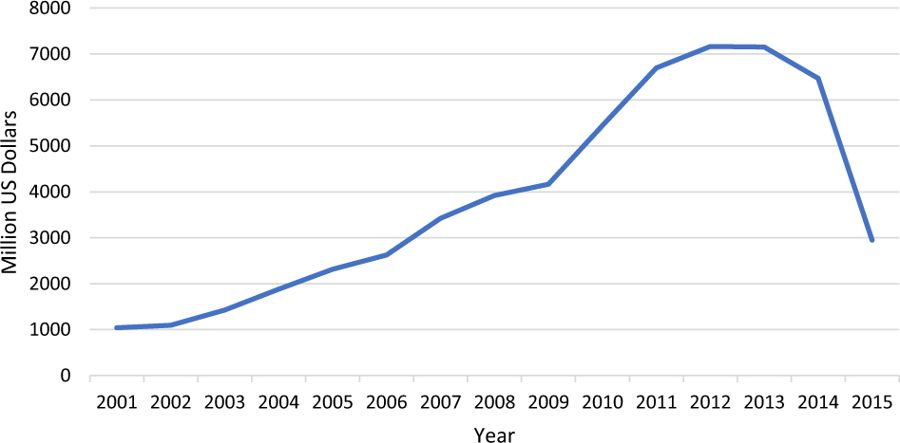

Before North Korea achieves sufficient deterrent capability, it supplements its capability with external balancing strategy. In particular, North Korea’s balancing strategy has two levels of considerations. At the global level, North Korea after the Korean War quickly signed two mutual military assistance treaties with the Soviet Union and China. After the Soviet–China relationship broke down, North Korea naturally sided with the more powerful Soviet Union to counterbalance the US. In the meantime, due to the breakdown of the Sino–Soviet relationship, China normalized its relations with the US, Japan, and later South Korea. China’s series of foreign policy shifts convinced North Korean leaders that China was unreliable. Nonetheless, the unexpected sudden collapse of the Soviet Union made it imperative for North Korea to find another major power to balance against the US and help with its domestic economy. China’s rapidly growing economy in the 1990s and its socialist ideology made it the only choice for North Korea to work with. Since China plays an important role in North Korea’s post-Cold War global balancing strategy, North Korean leaders decided to warm up the relations with China and dismiss China’s “treacheries” such as recognizing South Korea. Figures 1 and 2 show that the Chinese and North Korean leaders exchanged frequent visits since the late 1990s and bilateral trade grew exponentially. More recent studies on North Korea’s official attitude toward China also show that North Korea has maintained a high level of nominally positive view about China even when China hurts North Korea’s interests (Zhan, 2016; Zhang and Zinoviev, 2017). I will later explain why the attitude is “nominally positive.”

Fig. 1: Official meetings among Chinese and North Korean leaders. Data collected from NK News Leadership Tracker database (NK News, 2017)

Compared to global power balance, a small power cares more about the power balance at regional level (Kang, 2003; Rothstein, 1968). Among all states, ceteris paribus, a state is most concerned about its neighboring countries because they have an interest in shaping its domestic policies and geographic proximity means greater likelihood of war (Gause, 2007). Korea has a long history of foreign interference in its domestic politics. Therefore, its leaders have been wary of foreign influence. For example, North Korean official ideology, Juche, professes the pursuit of independence of any foreign influence in its domestic and foreign policy making.

Due to China’s history of interference in Korean politics and its growing capability, Korean leaders have been wary of China’s influence in the country. For example, among the founders of the Korean Workers’ Party, the ruling party of North Korea, were a group of Koreans who assisted the Chinese communists in China with the WWII and the Chinese civil war. They returned to Korea after the wars to help rebuild Korea. Because of their close relationship with the Chinese leaders, they were referred to as the “Yan’an faction” in Korea (Lankov, 2013), or “Yan’an group” (Buzo, 2016). Since Kim Il-Sung, the then leader of the Korean Workers’ Party (KWP), was backed by the Soviet Union, he was concerned about the strong influence of the Yan’an faction and China in the Korean politics. For instance, at the eve of the Korean War, the Yan’an faction was excluded from the war planning and China was uninformed of the war planning until September 1950 when Kim needed China’s help (Shen, 2003; Suh, 2004).

China’s support during the Korean War on the one hand helped the North Korean regime survive, but on the other hand worsened Kim’s concern as it strengthened the power of the Yan’an faction. Therefore, after the Korean War, Kim Il-Sung officially requested all foreign forces to withdraw from the Korean Peninsula (Chung and Choi, 2013). Nonetheless, the US ignored the request and the Soviet Union did not have military stationed in North Korea. The only foreign military in North Korea then belonged to China. Hence, Kim Il-Sung’s request was implicitly asking the Chinese to leave Korea in order to contain China’s influence in the post-war Korea. Once China withdrew the military, Kim Il-Sung purged the Yan’an faction from the KWP because he believed that they plotted with Chinese a coup against him. Since then, the pro-China political force in North Korea was eliminated, until the late 1990s when North Korea needed China’s assistance.

Similar to its military support during the war, China’s post-Cold War economic success on the one hand provides North Korea new trade sources to develop economic capability and fund the nuclear programs; whereas it also creates North Korea’s economic reliance on China. Economic dependence can be used as a source of power and control (Hirschman, 1980; Kirshner and Rawi, 1999; Knorr, 1975; Levy, 2003). As North Korea on average relies on China for more than eighty percent of its trade (International Trade Center, 2017), such a high level of trade reliance puts it in a disadvantaged position and could potentially threaten regime stability. In addition to economic influence, China’s economic reform has attracted great interest among North Korean elites and hence revived the pro-China faction in North Korea. One of the most powerful advocates of the Chinese style economic reform was Jang Song-Thaek, Kim Jong-Il’s brother-in-law and the Vice Chairman of the National Defense Committee. Since Jang oversaw North Korea’s economic cooperation with China, he developed a very good relationship with Chinese leaders. Under his management, dozens of Chinese-style special economic zones were established in North Korea. Jang and his followers could be viewed by Kim Jong-Un as a real threat to his authority.

This hypothesis is supported by my research on North Korea’s attitude of China. That work shows that, on the one hand, both Kim Jong-Il’s and Kim Jong-Un’s administrations maintain a nominally high level of positive general attitude toward China (Zhang and Zinoviev, 2017). On the other hand, if we examine closely different types of attitudes, we see very different patterns of attitude. For example, the positive attitude about economic interactions with China under the Kim Jong-Il administration rose when the bilateral trade volume increased. In comparison, the Kim Jong-Un administration has so strong resistance to China’s influence that the positive attitude has declined even when the trade volume increased. The difference in the responses to China’s economic influence can be explained by the differences in the domestic political conditions of the two regimes (Hilsman, 1971; Levy and Barnett, 1991, 1992; Schilling, 1962; Rose, 1998; Schweller, 2003, 2006). One reason why Kim Jong-Il did not have as strong resistance to China, as Kim Jong-Un does, is because the former enjoyed a higher level of legitimacy than the latter. Kim Jong-Il started governing North Korea alongside Kim Il-Sung in the 1970s, and hence gained legitimacy when he inherited the authority. In comparison, Kim Jong-Un did not enjoy much legitimacy when he inherited the throne. Firstly, Kim Jong-Un had little recognition in Korean society partly because the identities of Kim Jong-Il’s children were well protected from the public and partly because Kim Jong-Un spent most of his life outside North Korea. During my trip in North Korea, my local guides told me that they did not know who Kim Jong-Un was when he was announced to be the new leader. Secondly, Kim Jong-Un’s young age, lack of governing experience, and his identify of being the youngest son of Kim Jong-Il are his obstacles to gaining support among the senior officials in the regime. Therefore, despite the importance of regime survival at the global level, Kim Jong-Un is more worried about his own political survival in the regime and would view China’s influence and the domestic pro-China political force as major threats to his authority.

To gain legitimacy, Kim Jong-Un has been taking out his challengers. One year after he officially took over the power, he swiftly arrested and executed Jang Song-Thaek, the second most powerful person in North Korea, his uncle and designated mentor (Harlan, 2010). In Jang’s indictment, he was accused of organizing a faction against Kim Jong-Un and selling resources cheaply to China. At the same time, Kim Jong-Un recalled many North Korean businessmen in China and suspended all high level official interaction with China (Yonhap News, 2013).

Kim Jong-Un’s target list extends beyond Jang’s faction and includes potential challengers outside the country. For instance, Kim Jong-Nam, Kim Jong-Il’s eldest son who had been under China’s protection for years, was assassinated in February 2017, by North Korean agents in Malaysia. Even though Kim Jong-Nam openly announced his disinterest in the leadership position in North Korea (Chow and Park, 2017), his identity as Kim Jong-Il’s eldest son would have given him legitimacy to the North Korean throne. Moreover, Kim Jong-Nam’s close relationship with China makes him a potential powerful competitor of Kim Jong-Un with domestic and foreign support, if China wants to replace Kim Jong-Un. This speculation is supported by a recent attempted assassination of Kim Jong-Nam’s son by North Korean agents in China after the death of Kim Jong-Nam (Kong, 2017a).

In addition to removing competitors, Kim Jong-Un’s second approach to gaining legitimacy is economic development. It is estimated that the North Korean economy under Kim Jong-Un’s rule has been growing and reached a 3.9% growth rate in 2016, possibly driven by the nuclear and missile development programs (Kim and Chung, 2017). According to my North Korean guides, most of the North Korean urban economy has been somewhat liberalized and businesses and consumers practically follow a market mechanism in daily transactions, even though the economy is still a nominally state-run, planned economy. In his speech to the 7th KWP Congress, Kim Jong-Un made economic development as one of his priorities (Kim, 2017). In particular, he stressed continuing to improve self-reliance on food and energy as well as diversification of trade partners.

Re-Examining Today’s Situation

As I have shown, in spite of the nominal “friendship”, the China–North Korea relationship has not always been amicable. In fact, North Korean leaders, especially Kim Jong-Un, have been wary of China’s influence. The belief that China has leverage over North Korea and that its influence could change North Korea’s behavior is questionable. Thus, we need to revisit the question, why does a small, poor, isolated country want to pursue a costly, decades-long nuclear program despite heavy international pressure?

The short answer is survival. Survival is the priority for any government. Without survival, anything else is meaningless. For that reason, North Korean leaders are not suicidal or irrational. The cases of Iraq and Libya convinced North Korean leaders that the country needs nuclear weapon for security regardless of its cost. But before North Korea develops advanced nuclear capability, it needs China’s balance against the US. Thus, North Korea needs to maintain reasonably good relationship with the rising communist power. However, North Korea’s need for China does not mean that China can use leverage to direct North Korea’s behavior. The reason is that, firstly, North Korea needs China to counterbalance the US threat in its global level strategy, not to have China help the US undermine its own security. China’s recent vote in the UN for economic sanctions has again proven China an unreliable balancer.

If China fails to perform the balancing function, then North Korea could potentially treat China in the same way as it treats the US. For instance, a 2017 Korean Central News Agency commentary criticized China as “dancing to the tunes of the US” to “check its nuclear program (Kong, 2017b),” and warned China to “ponder over grave consequences to be entailed by its reckless act of chopping down the pillar of the DPRK–China relations (KCNA, 2017b).” Additionally, China’s unreliability would further motivate North Korea to accelerate the development of nuclear programs because its need for China would diminish as its nuclear capability continues to grow.

Secondly, it is rational for the North Korean leader to resist China’s influence. Kim Jong-Un cares about the survival of the regime, but his priority is his own political survival. Thus, the importance of the economic relations with China to Kim Jong-Un could be overestimated. Although China’s assistance indeed could improve the North Korean economy and regime stability, it is not viewed by North Korean leader as the leverage that China can use to order North Korea around. Rather, North Korea considers China’s economic assistance a form of service fee that North Korea deserves for “protecting peace and security of China” from the Western influence and potential US invasion (KCNA, 2017b). Moreover, the potential political threat that China presents to Kim Jong-Un could outweigh the benefits he and his regime could gain from China. As the “arduous march” in the mid-1990s shows, a strong economy is ideal but not necessary for a closed totalitarian regime to survive.

Potential Solution

To many policy makers, sanction is still a preferred solution partly because of its low cost of implementation and partly because they distrust North Korea. However, history shows that sanctions rarely change the target states’ behavior. To a society like North Korea that has already been closed and cut off from the international market, the long-term impact of sanction would be even more limited. As I have shown, it is nearly impossible for North Korea to give up nuclear weapon at this stage due to its concerns of the US threat and the desire to be more independent of Chinese influence.

It is argued that even if sanctions fail to persuade North Korea to give up nuclear weapons, they could jeopardize the North Korean economy, undermine the regime stability and eventually solve the nuclear problem from within the country. This is, I suggest, unfortunately wishful thinking. During my visit to North Korea, my guides told me that people were already “used to life under sanctions,” and that people generally believe that sanctions eventually will be lifted if the regime keeps developing the nuclear program. Additionally, the sanctions have been used by the North Korean propaganda to exemplify the Western aggression against North Korea and blame social problems on the West, especially the US. In other words, the sanctions can be used by the North Korean government to strengthen its legitimacy as being the protector of the country and further control society for security reasons.

Even if sanctions can make North Korean people upset about their government, it is unlikely that they can effectively coordinate and mobilize large-scale collective actions. For example, the North Korean political system encourages people to spy on each other and report others’ “counter-revolutionary” behavior or thoughts. During my trip in North Korea, one of my guides pretended to nap on the bus while eaves-dropping my conversation with the other guide. Therefore, North Koreans are constantly afraid that they could be reported by the people close to them. Additionally, it is very difficult to mobilize people in North Korea. The transportation infrastructure in North Korea is poorly maintained. When I travelled between North Korean provinces, the bus driver could only drive at approximately 30 km per hour (or 18.6 miles per hour) on the highway because he had to carefully avoid numerous potholes. Moreover, in order to travel between cities and villages, people need official permits, which can only be acquired if they have official business. The telecommunication network in North Korea is closely monitored by the government. Therefore, it is easy for the government to nip any potential mass movement in the bud. Politically, after the execution of Jang Song-Thaek, Kim Jong-Un has sidelined or purged the officials who he distrusted and filled the KWP leadership with his loyal followers, who are unlikely to defect in the near future. As a result, instead of seeking changes in the country, political dissidents or reformists would choose to leave the country.

Thus, the current approach of imposing sanctions on North Korea or asking China to impose harsher sanctions is unlikely to succeed. What can change North Korea’s behavior? Instead of asking for and expecting the impossible to happen, the US and the international community should focus on how to accept the fact that North Korea is a nuclear-capable state and learn how to deal with it. For instance, North Korea has sought for years to have bilateral negotiations with the US to normalize their relations. However, the US has insisted on complete denuclearization before any direct bilateral talk, which is unacceptable to North Korea.

The recent escalation of the crisis presents an opportunity for North Korea and the US to work things out. Kim Jong-Un cares about his political survival and regime survival. Therefore, despite its anti-US rhetoric, North Korea does not want to be the enemy of the world’s superpower. It develops nuclear weapons and relies on China to balance against the US because it has been subjected to hostile US policies and is isolated by the international community. Consequently, the greater threat North Korea encounters or the more isolated it is, the more it needs China in the short run to balance against the threat, the more North Korea becomes wary of China’s influence, and the more it would resist China’s domestic influence. Thus, North Korea could be in need of someone to balance against China. If the US continues its current policy, then North Korea may approach other neighboring powers such as Russia to balance against both China and the US.

After all, no one wants to see a nuclear war in the Korean Peninsula. If the US could step away from its current hostile policies against, and unreasonable requirements for, North Korea or if the international community can engage with North Korea instead of isolating it, then the North Korean leadership would not need to target nuclear weapons at the US and its allies; it could even welcome more political and economic forces to balance against China’s influence in the country. This approach is by no means easy due to the history and distrust between North Korea and the US. But it will be much better than other alternative outcomes.

References

- Buzo A (2016) The making of modern Korea. 3rd ed, Routledge, New York, NY.

- Kim C, Chung J (2017) North Korea 2016 economic growth at 17-year high despite sanctions–South Korea. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-northkorea-economy-gdp/north-korea-2016-economic-growth-at-17-year-high-despite-sanctions-south-korea-idUKKBN1A6083

- Center for Strategic and International Studies (2017) North Korean missile launches. Missile Threat. https://missilethreat.csis.org/north-korea-missile-launches-1984-present/. Accessed 1 Jan 2017

- Chow E, Park JM (2017) North Korea suspected behind murder of leader’s half-brother. Reuters. https://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-northkorea-malaysia-kim/north-korea-suspected-behind-murder-of-leaders-half-brother-u-s-sources-idUKKBN15T1EA

- Chung JH, Choi M (2013) Uncertain allies or uncomfortable neighbors? Making sense of China–North Korea relations, 1949–2010 Pac Rev 26(3):243–264. https://doi.org/10.1080/09512748.2012.759262

- Clover C, Harris B, Lockett H (2017) North Korean companies in China ordered to close. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/be406ed8-a4b3-11e7-9e4f-7f5e6a7c98a2?mhq5j=e5

- Doubek J (2017) China moves to limit fuel, textile trade with North Korea. NPR. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/23/553087705/china-moves-to-limit-fuel-textile-trade-with-north-korea

- Dyer G (2016) US pressures China over North Korea relationship. https://www.ft.com/content/a527c3c6-b5c0-11e5-b147-e5e5bba42e51

- Erickson SA (2001) Economic and technological trends affecting nuclear nonproliferation. Nonproliferation Rev Summer: 40–54. http://www.nonproliferation.org/wp-content/uploads/npr/82erick.pdf

- Epstein W (1977) Why states go—and don’t go—nuclear Ann Am Acad Political Social Sci 430(1):16–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271627743000104

- Gause FG (2007) Threats and threat perceptions in the Persian Gulf Region Middle East Policy 14(2):119–125

- Harlan C (2010) North Korea succession: Kim Jong Il appoints Jang Song Taek caretaker for Kim Jong Eun. Washington Post. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/08/15/AR2010081503356.html?sid=ST2010083105101

- Hilsman R (1971) The politics of policy making in Defense and Foreign Affairs. Rowman and Littlefield, New York, NY

- Hirschman A (1980) National power and the structure of Foreign Trade. University of California Press, Berkeley

- International Trade Centre (2017) Trade map.

www.intracen.org/marketanalysis. Accessed 13 July 2017 - Jervis R (1976) Perception and misperception in international politics. Princeton University Press, New Jersey, NJ

- Kang D (2003) Getting Asia wrong: the need for new analytical frameworks Int Secur 27(4):57–85un calls for stubborn struggle against U.S. KCNA. https://kcnawatch.co/newstream/1509260484-528114070/rodong-sinmun-calls-for-stubborn-struggle-against-u-s/

- KCNA (2017b) Commentary on DPRK–China relations. KCNA. http://www.kcna.kp/kcna.user.article.retrieveNewsViewInfoList.kcmsf#this

- Kim C (2017) Commentary on DPRK–China relations. Korean Central News Agency. http://www.kcna.kp/kcna.user.article.retrieveNewsViewInfoList.kcmsf#this

- Kim JU (2016) Kim Jong Un’s speeches at the 7th Workers’ Party Congress. https://www.ncnk.org/resources/publications/KJU_Speeches_7th_Congress.pdf

- Kirshner J, Rawi A (1999) Strategy, economic relations, and the definition of national interests Secur Stud 9(1/2):119–56

- Knorr K (1975) The power of nations: the political economy of international relations. Basic Books, New York, NY

- Kong K (2017a) China breaks up plot to kill Kim Jong Un’s nephew, Report Says. Bloomberg Polit. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2017-10-30/china-breaks-up-plot-to-kill-kim-jong-un-s-nephew-report-says

- Kong K (2017b) North Korea Says China “Dancing to U.S. Tune” in rare spat. Bloomberg Polit. https://www.bloomberg.com/politics/articles/2017-02-24/north-korea-says-china-dancing-to-u-s-tune-in-rare-criticism

- Kristensen HM, Robert SN (2017) A history of US nuclear weapons in South Korea Bull At Sci 73(6):349–57

- Lankov A (2013) The real North Korea: life and politics in the failed Stalinist Utopia. Oxford University Press

- Levy JS, Barnett MN (1991) Domestic sources of alliances and alignments: the case of Egypt, 1962–1973 Int Organ 45(3):369–395

- Levy JS, Barnett MN (1992) Alliances formation, domestic political economy, and third world security Jerus J Int Relat 14(4):19–40

- Levy J (2003) Balances and balancing: concepts, propositions, and research design. In: John AV, Colin E (eds) Realism and the balance of power: a new debate. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ

- NK News (2017) NK leadership tracker. www.nknews.org. Accessed 1 Jan 2017

- Office of the Press Secretary (2014) Press conference with President Obama and President Park of the Republic of Korea. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2014/04/25/press-conference-president-obama-and-president-park-republic-korea

- Powell R (1999) In the shadow of power: states and strategies in international politics. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Rose G (1998) Neoclassical realism and theories of foreign policy World Polit 51(1):144–172

- Rothstein R (1968) Alliances and small powers. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

- Schilling WR (1962) The politics of National Defense: Fiscal 1950. In: Schilling WR, Hammond PY, Snyder GH (eds) Strategy, politics, and defense budgets. Columbia University Press, New York, NY

- Schroeder P (1994) Historical reality vs. neo-realist theory Int Secur 19(1):108–48

- Schwartz S (2008) The costs of U.S. nuclear weapons. Nuclear threat initiative. http://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/costs-us-nuclear-weapons/. Accessed 9 Dec 2017

- Schweller RL (1994) Bandwagoning for profit: bringing the revisionist state back Int Secur 19(1):72–107

- Schweller RL (2003) The progressiveness of neoclassical realism. In: Elman C, Elman MF (eds) Progress in international relations theories: appraising the field. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA

- Schweller RL (2006) Unanswered threats: political constraints on the balance of power. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ

- Shen J (2003) Weihu dongbeiya anquan de dangwu zhi ji [the urgent task in safe-guarding Northeast Asian security] Shijie Jingji Yu Zhengzhi [World Econ Polit] 9:55–60

- Suh D (ed.) (2004) Bukhan munhon yongu [studies of North Korean documents]. Institute for Far Eastern Studies, Seoul

- Walt S (1985) Alliance formation and the balance of world power Int Secur 9(4):3–43

- Walt S (1987) The origins of alliances. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY

- Waltz K (1979) Theory of international relations. Addison-Wesley, Reading, MA

- Waltz K (1990) Nuclear myths and political realities Am Political Sci Rev 84(3):731

- Yonhap News (2013) N.K. businessmen in China summoned back after Jang’s execution. Yonhap News. http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/northkorea/2013/12/14/82/0401000000AEN20131214001400315F.html

- Zahn H (2017) Kim Jong Un is dangerous and a risk-taker, but not a “madman,” analysts say. PBS News Hour. https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/analysis-kim-jong-un-is-dangerous-and-unpredictable-but-not-a-madman

- Zhan D (2016) Analysis of changes in North Korea’s cognition of China Korean J Def Anal 28(2):199–221

- Zhang W, Zinoviev D (2017) Semantic network analysis of North Korean–Chinese relationships. In: American Political Science Association 2017. San Francisco, CA. https://apsa2017-apsa.ipostersessions.com/default.aspx?s=2B-C4-89-82-EB-CA-83-AD-14-CB-4F-B3-97-64-00-72

Originally published by Palgrave Communications 16:4 (2018) under the terms of a Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.