By Adrian Phillips

Author and Historian

In 1941, as his time in office drew to a close, the head of the British Civil Service, Sir Horace Wilson, sat down to write an account of the government policy with which he had been most closely associated. It was also the defining policy of Neville Chamberlain, the Prime Minister whom Wilson had served as his closest adviser throughout his time in office. It had brought Chamberlain immense prestige, but this had been followed very shortly afterwards by near-universal criticism. Under the title ‘Munich, 1938’, Wilson gave his version of the events leading up to the Munich conference of 30 September 1938, which had prevented – or, as proved to be the case, delayed – the outbreak of another world war at the cost of the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia. By then the word ‘appeasement’ had acquired a thoroughly derogatory meaning. Chamberlain had died in 1940, leaving Wilson to defend their joint reputation. Both men had been driven by the highest of motivations: the desire to prevent war. Both had been completely convinced that their policy was the correct one at the time and neither ever admitted afterwards that they might have been wrong.

After he had completed his draft, Wilson spotted that he could lay the blame for appeasement on someone else’s shoulders. Better still, it was someone who now passed as an opponent of appeasement. In an amendment to the typescript, he pointed out that in 1936, well before Chamberlain became Prime Minister, Anthony Eden, the then Foreign Secretary, had stated publicly that appeasement was the government’s policy. The point seemed all the more telling as Eden had been edged out of government by Chamberlain and Wilson in early 1938 after a disagreement over foreign policy. Eden had gone on to become a poster-boy for the opponents of appeasement, reaping his reward in 1940 when Chamberlain fell. Chamberlain’s successor, Winston Churchill, had appointed Eden once again as Foreign Secretary. Wilson was so pleased to have found reason to blame appeasement on Eden that he pointed it out a few years later to the first of Chamberlain’s Cabinet colleagues to write his memoirs.

Wilson’s statement was perfectly accurate, but it entirely distorted the truth, because it ignored how rapidly and completely the meaning of the word ‘appeasement’ had changed. When Eden first used the word, it had no hostile sense. It meant simply bringing peace and was in common use this way. ‘Appease’ also meant to calm someone who was angry, again as a positive act, but Eden never said that Britain’s policy was to ‘appease’ Hitler, Nazi Germany, Mussolini or Fascist Italy. Nor, for that matter, did Chamberlain use the word in that way. The hostile sense of the word only developed in late 1938 or 1939, blending these two uses of the word to create the modern sense of making shameful concessions to someone who is behaving unacceptably. The word ‘appeasement’ has also become a shorthand for any aspect of British foreign policy of the 1930s that did not amount to resistance to the dictator states. This is a very broad definition, and it should not mask the fact that the word is being used here in its modern and not its contemporary sense. The foreign policy that gave the term a bad name was a distinct and clearly identifiable strategy that was consciously pursued by Chamberlain and Wilson.

When Chamberlain became Prime Minister in May 1937, he was confronted by a dilemma. The peace of Europe was threatened by the ambitions of the two aggressive fascist dictators, Hitler in Germany and Mussolini in Italy. Britain did not have the military strength to face Germany down; it had only just begun to rearm after cutting its armed forces to the bone in the wake of the First World War and was at the last gasp of strategic over-reach with its vast global empire. Chamberlain chose to solve the problem by setting out to develop a constructive dialogue with Hitler and Mussolini. He hoped to build a relationship of trust which would allow the grievances of the dictator states to be settled by negotiation and to avoid the nightmare of another war. In other words, Chamberlain sought to appease Europe through discussion and engagement. In Chamberlain’s eyes this was a positive policy and quite distinct from what he castigated as the policy of ‘drift’ that his predecessors in office, Ramsay MacDonald and Stanley Baldwin, had pursued. Under their control, progressive stages in aggression by the dictators had been met with nothing more than ineffectual protests, which had antagonised them without deterring them.

Chamberlain’s positive approach to policy was the hallmark of his diplomacy. He wanted to take the initiative at every turn, most famously in his decision to fly to see Hitler at the height of the Sudeten crisis. Often his initiatives rested on quite false analyses; quite often the dictators pre-empted him. But Chamberlain was determined that no opportunity for him to do good should be allowed to escape. The gravest sin possible was the sin of omission. At first his moves were overwhelmingly aimed at satisfying the dictators. Only after Hitler’s seizure of Prague in March 1938 did deterring them from further aggression become a major policy goal. Here, external pressures drove him to make moves that ran counter to his instincts, but they were still usually his active choices. Moreover, the deterrent moves were balanced in a dual policy in which Hitler was repeatedly given fresh opportunities to negotiate a settlement of his claims, implicitly on generous terms.

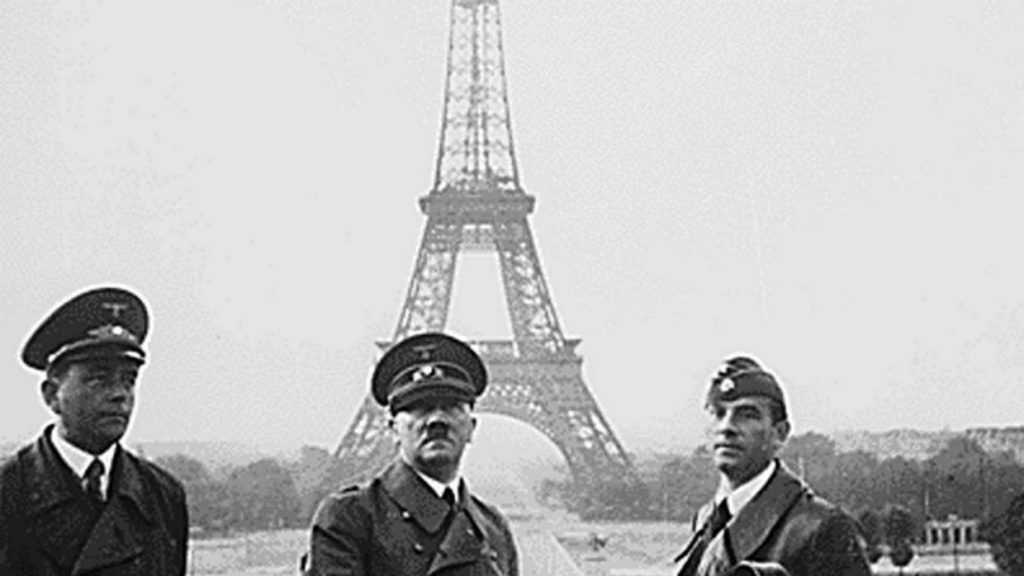

Appeasement reached its apogee in the Czech crisis of 1938. Chamberlain was the driving force behind the peaceful settlement of German claims on the Sudetenland. He was rewarded with great, albeit short-lived, kudos for having prevented a war that had seemed almost inevitable. He also secured an entirely illusory reward, when he tried to transform the pragmatic and unattractive diplomatic achievement of buying peace with the independence of the Sudetenland into something far more idealistic. Chamberlain bounced Hitler into signing a bilateral Anglo-German declaration that the two countries would never go to war. Chamberlain saw this as the first building block in creating a lasting relationship of trust between the two countries. It was this declaration, rather than the dismemberment of Czechoslovakia under the four-power treaty signed by Britain, France, Germany and Italy, that Chamberlain believed would bring ‘peace for our time’, the true appeasement of Europe. At the start of his premiership, Chamberlain had yearned to get ‘onto terms with the Germans’; he thought that he had done just that.

Appeasing Europe through friendship with the dictators also required the rejection of anything that threatened this friendship. One of the most conspicuous threats was a single individual: Winston Churchill. Almost from the beginning of Hitler’s dictatorship Churchill had argued that it was vital to Britain’s interests to oppose Nazi Germany by force, chiefly by rearming. Unlike most other British statesmen, Churchill recognised in Hitler an implacable enemy and he deployed the formidable power of his rhetoric to bring this home in Parliament and in the press. But Churchill was a lone voice. When he had opposed granting India a small measure of autonomy in the early 1930s, he had moved into internal opposition to the Conservative Party. Only a handful of MPs remained loyal to him. Churchill was also handicapped by a widespread bad reputation that sprang from numerous examples of his poor judgement and political opportunism.

Chamberlain was determined on a policy utterly opposed to Churchill’s view of the world. He enjoyed a very large majority in Parliament and faced no serious challenge in his own Cabinet. Chamberlain and Wilson were so convinced that their policy was correct that they saw opposition as dangerously irresponsible and had no hesitation in using the full powers at their disposal to crush it. Churchill never had a real chance of altering this policy. It would have sent a signal of resolve to Hitler to bring him back into the Cabinet, but this was precisely the kind of gesture that Chamberlain was desperate to avoid. Moreover, Chamberlain and Wilson each had personal reasons to be suspicious of Churchill as well as sharing the prevalent hostile view of him that dominated the political classes. Wilson and Churchill had clashed at a very early stage in their careers and Chamberlain had had a miserable time as Churchill’s Cabinet colleague under Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin. Chamberlain and Wilson had worked closely to fight a – largely imaginary and wildly exaggerated – threat from Churchill’s support for Edward VIII in the abdication crisis of 1936.

Churchill was right about Hitler and Chamberlain was wrong. The history of appeasement is intertwined with the history of Churchill. According to legend Churchill said, ‘Alas, poor Chamberlain. History will not be kind to him. And I shall make sure of that, for I shall write that history.’ Whatever Churchill might actually have said on the point barely matters; the witticism expresses a mindset that some subsequent historians have striven to reverse. The low opinion of Chamberlain is the mirror image of the near idolatry of Churchill. In some cases, historians appear to have been motivated as much by dislike of Churchill – and he had many flaws – as by positive enthusiasm for Chamberlain. Steering the historical debate away from contemporary polemic and later hagiography has sometimes had the perverse effect of polarising the discussion rather than shifting it onto emotionally neutral territory. Defending appeasement provides perfect material for the ebb and flow of academic debate, often focused on narrow aspects of the question. At the last count, the school of ‘counter-revisionism’ was being challenged by a more sympathetic view of Chamberlain.

Chamberlain’s policy failed from the start. The dictators were happy to take what was on offer, but gave as good as nothing in return. Chamberlain entirely failed to build worthwhile relationships. Chamberlain’s advocates face the challenge that his policy failed entirely. Chamberlain’s defenders advance variants of the thesis that Wilson embodied in ‘MUNICH, 1941’: that there was no realistic alternative to appeasement given British military weakness. This argument masks the fact that it is practically impossible to imagine a worse situation than the one that confronted Churchill, when he succeeded Chamberlain as Prime Minister in May 1940. The German land attack in the west was poised to destroy France, exposing Britain to a German invasion. It also ducks the fact that securing peace by seeking friendship with the dictators was an active policy, pursued as a conscious choice and not imposed by circumstances.

Chamberlain’s foreign policy is by far the most important aspect of his premiership and the attention that it demands has rather crowded out the examination of other aspects of his time at Downing Street. Discussion of his style of government has focused on the accusation that he imposed his view of appeasement on a reluctant Cabinet, which has been debated with nearly the same vigour as the merits or otherwise of the policy itself. In the midst of this, little attention has been paid to Wilson, even though Chamberlain’s latest major biographer – who is broadly favourable to his subject – concedes he was ‘the éminence grise of the Chamberlain regime … gatekeeper, fixer and trusted sounding board’.Martin Gilbert, one of Chamberlain’s most trenchant critics, made a start on uncovering Wilson’s full role in 1982 with an article in History Today, but few have followed him. There have been an academic examination of his Civil Service career and an academic defence of his involvement in appeasement.Otherwise, writers across the spectrum of opinions on appeasement have contented themselves with the unsupported assertion that Wilson was no more than a civil servant.Wilson does, though, appear as a prominent villain along with Chamberlain’s shadowy political adviser, Sir Joseph Ball, in Michael Dobbs’s novel about appeasement,Winston’s War.

Dismissing Wilson as merely a civil servant begs a number of questions. The British Civil Service has a proud tradition and ethos of political neutrality, but it strains credulity to expect that this has invariably been fully respected. Moreover, at the period when Wilson was active, the top level of the Civil Service was still evolving, with many of its tasks and responsibilities being fixed by accident of personality or initiative from the Civil Service side. Wilson’s own position as adviser to the Prime Minister with no formal job title or remit was unprecedented and has never been repeated. Chamberlain valued his political sense highly and Wilson did not believe that his position as a civil servant should restrict what he advised on political tactics or appointments. Even leaving the debate over appeasement aside, Wilson deserves attention.

Wilson was so close to Chamberlain that it is impossible to understand Chamberlain’s premiership fully without looking at what Wilson did. The two men functioned a partnership, practically as a unit. Even under the extreme analysis of the ‘mere civil servant’ school whereby Wilson was never more than an obedient, unreflecting executor of Chamberlain’s wishes, his acts should be treated as Chamberlain’s own acts and thus as part of the story of his premiership. It is practically impossible to measure Wilson’s own autonomous and distinctive input compared to Chamberlain’s, but there can be no argument that he represented the topmost level of government.

Wilson’s hand is visible in every major aspect of Chamberlain’s premiership and examining what he did throws new light almost everywhere. Wilson’s influence on preparations for war – in rearming the Royal Air Force and developing a propaganda machine – makes plain that neither he nor Chamberlain truly expected war to break out. One of the most shameful aspects of appeasement were the measures willingly undertaken to avoid offending the dictators, either by government action or by comment in the media; Wilson carries a heavy responsibility here.

Above all it was Wilson’s role in foreign policy that defined his partnership with Chamberlain and the Chamberlain premiership as a whole. He was also the key figure in the back-channel diplomacy pursued with Germany that showed the true face of appeasement. Wilson carries much of the responsibility for the estrangement between Chamberlain and the Foreign Office, which was only temporarily checked when its political and professional leaderships were changed. Chamberlain and Wilson shared almost to the end a golden vision of an appeased Europe, anchored on friendship between Britain and Germany, which was increasingly at odds with the brutal reality of conducting diplomacy with Hitler. The shift to a two-man foreign policy machine culminated in the back-channel attempts in the summer of 1939 intended to keep the door open to a negotiated settlement of the Polish crisis with Hitler, but which served merely to convince him that the British feared war so much that they would not stand by Poland. Chamberlain and Wilson had aimed to prevent war entirely; instead they made it almost inevitable.

Originally published by History News Network, 12.01.2019, reprinted with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.