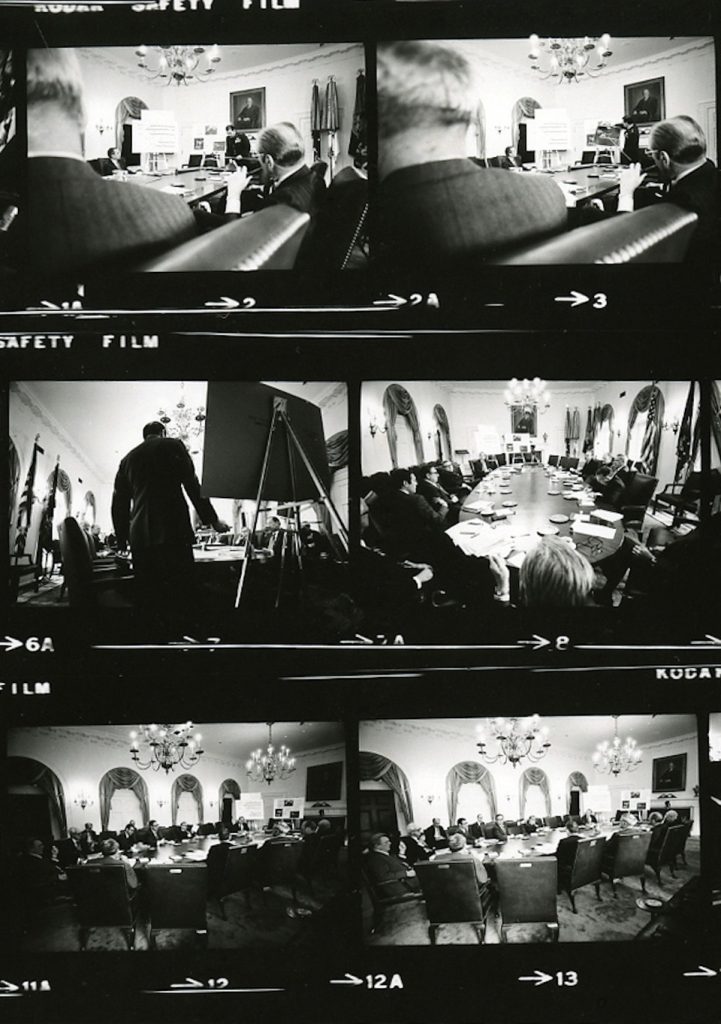

It began with an image – the first on the White House Photography Office’s 4,527th roll of film for the Ford administration.

By Dr. Mattias E. Fibiger

Assistant Professor of Business Administration

Harvard Business School

He snaps a photograph of President Gerald Ford, who leans back in a tall Cabinet Room chair, smoking a pipe and listening intently to CIA Director Colby. The image is the first on the White House Photography Office’s 4,527th roll of film for the Ford administration.

The sun beats through the White House’s bulletproof glass as Colby offers the CIA’s latest appraisal of the whereabouts of the American hostages. Two days ago, on Monday, Ford learned that an American commercial shipping freighter, the S.S. Mayaguez, had been assaulted and detained by the Khmer Rouge navy. The crew of forty American civilians had been taken captive and moved to Koh Tang, a meager, elongated island lying about thirty miles off the Cambodian coast. No U.S. military forces were on hand to attempt a rescue, but on Tuesday evening American aircraft spotted a flotilla of two speedboats and one fishing trawler departing Koh Tang. The pilots were able to sink one of the speedboats and force another to turn back. But the fishing trawler continued to ply toward the mainland port city of Kompong Som, unimpeded by warning shots and clouds of tear gas. One of the pilots reported seeing thirty to forty people—possibly Caucasians—in a huddled mass on the trawler’s bow.

He takes another photo. “The Cambodians have apparently transported at least some of the American crew from Koh Tang Island to the mainland, putting them ashore at Kompong Som port at about 11:00 last night, Washington time,” Colby says. The CIA chief suspects that other hostages remain on Koh Tang.[1]

Four National Security Council meetings in the past three days, all of them captured on his film. Yesterday’s second meeting stretched on till well after midnight. There, the nation’s top military and political minds crafted the United States’ response to the seizure of the Mayaguez. They opted to launch coordinated amphibious assaults against Koh Tang and the Mayaguez herself, which rested idly nearby. And they decided to pummel Kompong Som with airstrikes. Kissinger, who served as both secretary of state and national security advisor, offered a justification for bombing the mainland: “We should hit targets at Kompong Som and the airfield and say that we are doing it to suppress any supporting action against our operations to regain the ship and seize the island.” The members of the Ford administration also hoped that military action directed against Cambodia proper would compel the Khmer Rouge to release any American hostages it had transported to the mainland.

If he had picked up a copy of the New York Times that Wednesday morning and glanced at the bottom of the front page, he could have read about “high-ranking Administration sources familiar with military planning” who had “said privately that the seizure of the vessel might provide the test of American determination in Southeast Asia that, they asserted, the United States has viewed as important since the collapse of allied governments in South Vietnam and Cambodia.” (Phnom Penh had been taken over by communist forces a month ago, and Saigon had followed suit two weeks later.)

He could have seen truth in the Times’s narrative. On Tuesday night, he heard Kissinger affirm the importance of responding to the seizure of the Mayaguez in a way that would reestablish the United States’ international credibility: “I think we should do something that will impress the Koreans and the Chinese.” Ford’s counsel, speechwriter, and longtime political aide Bob Hartmann meanwhile focused on the domestic political arena, on the president’s personal credibility. “This crisis, like the Cuban missile crisis, is the first real test of your leadership,” Hartmann told the president. “We should not just think of what is the right thing to do, but of what the public perceives.”

He witnessed another discussion during Tuesday night’s NSC meeting. The administration displayed a remarkable degree of unity behind the plan to bomb the Cambodian mainland. But they divided over how to execute that plan. Ford suggested using B-52 bombers stationed in Guam. Secretary of Defense Schlesinger thought it better to use jets based on the aircraft carriers hastening toward the Gulf of Thailand. “The B-52’s are a red flag on the Hill,” Schlesinger explained. “Moreover, they bomb a very large box and they are not so accurate. They might generate a lot of casualties outside the exact areas that we would want to hit.” The meeting adjourned without Ford deciding between the B-52s and the jets on the aircraft carriers.

The camera clicks again. General Jones of the Joint Chiefs has just finished telling Ford that both the B-52s and the carrier jets have been put on alert. Jones awaits the president’s orders.

The man behind the lens is not a policymaker—not a Kissinger, a Schlesinger, or a Scowcroft. Lecturing the most powerful men in the world is not included in his job description, and interjecting in the discussion is a fireable offense. But, he thinks, “I can’t contain myself. I am almost certainly the only person in the room who has been in Cambodia.” He speaks up.[2]

“Has anyone considered that this might be the act of a local Cambodian commander who has just taken it into his own hands to halt any ship that comes by? Has anyone stopped to think that he might not have gotten his orders from Phnom Penh? If that’s what happened, you know, you can blow the whole place away and it’s not gonna make any difference. Everyone here has been talking about Cambodia as if it were a traditional government. Like France. We have trouble with France, we just pick up the telephone and call. We know who to talk to. But I was in Cambodia just two weeks ago, and it’s not that kind of government at all. We don’t even know who the leadership is. Has anyone considered that?”[3]

Several seconds of silence.

Then Ford orders the planes stationed on the aircraft carrier U.S.S. Coral Sea to carry out the bombing operation. The B-52s should remain on alert, but barring any unforeseen developments they should not be used. “Henry,” the president asks, “what do you think?”

“My recommendation is to do it ferociously. We should not just hit mobile targets, but others as well.”

The issue decided, the members of the National Security Council move on to other details of crisis management and military planning. They discuss the timing of the attack, the possibility of collateral damage, and the need to consult with Congress.

David Kennerly, the 28-year old White House photographer, raises the camera to his eye and continues taking pictures. His lens, snapping, surveys the room. He is on roll number 4,536. The record will not reflect his comments.[4]

Appendix

Notes

- The CIA’s estimate of the situation was flawed. All the American hostages had been moved to Kompong Som, and shortly thereafter were moved once again to Koh Rong Sam Lem, another of Cambodia’s small coastal islands.

- {‘epub-alternate’: ‘I have edited Kennerly’s recollections to place his thoughts in the present tense. David Hume Kennerly, Shooter (New York: Newsweek Books, 1979), pp. 176-177.’, ‘standard’: ‘I have edited Kennerly’s recollections to place his thoughts in the present tense.’}

- {‘epub-alternate’: ‘Gerald R. Ford, A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford (New York: Harber & Row, 1979), pp. 279-280. A different version of the outburst appears in Kennerly’s memoirs: “Has it occurred to anyone that this whole thing may have been the act of one local commander taking matters into his own hands and seizing the ship?” See Kennerly, Shooter, 177.’, ‘standard’: ‘A different version of the outburst appears in Kennerly’s memoirs: “Has it occurred to anyone that this whole thing may have been the act of one local commander taking matters into his own hands and seizing the ship?” See Kennerly, Shooter, 177.’}

- By “record” I mean the government’s official record of the day’s proceedings. The minutes of the NSC meeting do not list Kennerly as a participant or note his contribution to the discussion. Kennerly’s outburst is, however, documented in the unofficial record. Both Ford and Kennerly mention it in their memoirs, although they recall it differently. The unofficial record is then both more and less reliable than its official counterpart. Indispensable for the historian, it reveals what the official record tends to elide, including “water cooler” discussions that take place outside of earshot of the designated note-taker, unspoken or unspeakable motivations, and personal conflicts. But because the unofficial record rejects the imperative of standardization, its treasures are always open to question. For the unofficial record of NSC meeting of May 14, 1975 on the Mayaguez crisis see, among others, Ford, A Time to Heal and Kennerly, Shooter. For the official record see “Minutes of National Security Council Meeting,” in US Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976. Volume X: Vietnam, January 1973-July 1975 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2010), 1021-1036.

Bibliography

- David Hume Kennerly, Shooter (New York: Newsweek Books, 1979), pp. 176-177.

- Gerald R. Ford, A Time to Heal: The Autobiography of Gerald R. Ford (New York: Harper & Row, 1979), pp. 279-280.

- Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, “Minutes of National Security Council Meeting,” (accessed April 10, 2013).

- Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Photographs for May 14, 1975, (accessed January 28, 2013).

- Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library, Photographs for May 14, 1975, http://www.fordlibrarymuseum.gov/library/whphotos/19750514whpo.pdf (accessed January 28, 2013).

- “Minutes of National Security Council Meeting,” in US Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969-1976. Volume X: Vietnam, January 1973-July 1975 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 2010).

- Philip Shabecoff, “Silence in Washington,” New York Times, May 14, 1975.

Originally published by The Appendix 1:4 (October 2013) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.