Exploring rich and surprising form of Ceylonese nationalism inflected by late-Victorian radicalism.

By Dr. Kristin Mahoney

Associate Professor of English

Michigan State University

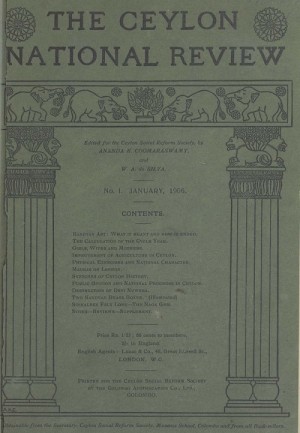

The Ceylon National Review (1906-1911) was the official organ of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, an organization founded by the art historian Ananda Coomaraswamy in an effort to combat colonial influence and reinvigorate Ceylonese cultural production. Coomaraswamy also served as an editor at the Ceylon National Review. This essay focuses on the manner in which Coomaraswamy, in the essays he contributed to and solicited for the journal, fostered transethnic Ceylonese nationalism and anticolonial resistance as well as transnational engagement with British countercultural movements and radical thought. Paying particular attention to Coomaraswamy’s interest in socialist aestheticism, Theosophy, and British discourses concerning vegetarianism, I foreground the highly cosmopolitan inflection of Coomaraswamy’s brand of Ceylonese nationalism as expressed in the pages of the Ceylon National Review. In the essays he wrote and selected for publication in the periodical, Coomaraswamy integrated the discourses of anticolonialism and socialist aestheticism and allowed British and Ceylonese vegetarians and Theosophists to speak in relation to one another, engendering a rich and surprising form of Ceylonese nationalism inflected by late-Victorian radicalism.[1]

In January of 1906, the inaugural issue of the Ceylon National Reviewannounced the founding of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, an organization devoted—as indicated in its manifesto—to “[discouraging] the thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European habits and customs” and to combating Eastern nations’ loss of “individuality” resulting from “the adoption of a veneer of Western habits and customs” (ii).[2] Excessive devotion to and investment in Western aesthetic ideals had resulted in the “neglect of the elements of superiority in the culture and civilization of the East” (ii). With this in mind, the Society was especially “anxious to encourage the revival of native arts and sciences” and “to re-create a local demand for wares locally made, as being in every respect more fitted to local needs than any mechanical Western-manufactured goods are likely to become” (iii). Anticolonial resistance in Ceylon, this manifesto asserted, would be organized around a revival of Ceylonese arts and crafts.[3] The Ceylon National Review, the organ of the society, would work to promote the goals of the society, publishing “essays of an historical or antiquarian character and articles devoted to the consideration of present day problems, especially those referred to in the Society’s manifesto,” with the hope that “these may have some effect towards the building up of public opinion on national lines and uniting the Eastern Races of Ceylon on many points of mutual importance.”[4] This was to be a medium for transethnic Ceylonese nationalism that spoke to and brought together the population of Ceylon around a critique of colonial influence and an appreciation of Ceylonese cultural production.[5]

The Ceylon National Review was co-edited (along with W. Arthur de Silva [1869-1942]) by the Society’s founder and president, Ananda Coomaraswamy. Coomaraswamy, born in Colombo to a Tamil father and an English mother and raised and educated in the sciences in England, had returned to the island in 1903 to serve as the director of the Mineralogical Survey of Ceylon.[6] During his travels, the deleterious effects of British imperialism on Ceylon captured his attention, and he began to refashion himself as an art historian and anticolonial activist. According to Coomaraswamy, the ceding of Ceylon to the British had been accompanied by the dissolution of the conditions that had strengthened traditional arts and crafts in the nation, such as their popular nature, their function within ritual, and the regulative power of the guilds. He believed that the island’s artistic traditions had been undone by the “growth of commercialism—that system of production under which the work of European machines and machine-like men has in the East driven the village weaver from his loom, the craftsman from his tools, the ploughman from his songs, and has divorced art from labour” (Mediaeval Sinhalese Art vi). Coomaraswamy founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society along with the Ceylon National Review in order to address the causes of this degeneration and to renew local interest in native languages and literature as well as vegetarianism and national dress. Following his founding of the Society, he went on to publish numerous highly significant treatises on Indian and Ceylonese art history, including Mediaeval Sinhalese Art (1908) and The Arts and Crafts of India and Ceylon (1913); played a crucial role in introducing British modernists, including Eric Gill and Jacob Epstein, to Indian sculpture; and in 1917 assumed the position of curator of the Indian Section of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.[7] His years in Ceylon in the 1900s thus represent a turning point in his career, when he turned his scientifically-trained eye to his home country and the ills of imperialism, and began generating a cultural antidote to colonization.

Coomaraswamy should be understood as one of the most influential figures to facilitate Western engagement with Indian and Ceylonese art. In addition, his thinking became central to Ceylonese modernism and informed both the Indian and Ceylonese independence movements. Attending here to an early and highly significant moment in Ananda Coomaraswamy’s career, when he began to formulate his particular brand of aesthetically-based nationalism, illuminates the cosmopolitan roots of his critique of imperialism, the manner in which the British Arts and Crafts, Theosophist, and vegetarian movements, inflected his anticolonial thinking. Coomaraswamy turned to Victorian tools to counter the persistence of Victorian imperialism in Ceylon, and Western modes of religious bohemianism and political dissidence pollinated his approach to anticolonialism. Focusing on this transitional moment in his art historical thinking, when he was most clearly engaged with British socialist aestheticism, British vegetarian thought, and Theosophy, allows for new insight into the intellectual development of one of the most important figures in South Asian political and art history. In this essay, I will consider Coomaraswamy’s work with the Ceylon National Review, focusing on the essays he contributed to and solicited for the periodical as editor.[8] The transnational dialogue fostered within the pages of this periodical established a rich and strange foundation for early twentieth-century Ceylonese nationalism. Examining the repurposing of, for example, William Morris’s socialist aestheticism along with the engagement with Henry Salt and Annie Besant in the Ceylon National Review provides insight into the manner in which late-Victorian countercultural movements circulated transnationally and were turned to disparate ends as they were revised and reformulated within subaltern cosmopolitanisms.[9] As Elleke Boehmer notes in her work on anticolonial nationalisms, “anti-colonial intelligentsias, poised between the cultural traditions of home on the one hand and of their education on the other, occupied a site of potentially productive inbetweenness where they might observe other resistance histories and political approaches in order to work out how themselves to proceed” (21). Coomaraswamy’s inbetweenness and his deep connectedness to radical anti-capitalist cultural formations in England, designed to counteract the effects of industrialism and commodity culture, allowed him to perceive how these approaches might be implemented in the contestation of comparable problems engendered by the import of British taste and ideologies of labor to Ceylon.

Coomaraswamy’s development of a transethnic and cosmopolitan mode of Ceylonese nationalism emerges from a very specific moment in the island’s history as well as his own complex, “inbetween” relationship to Ceylon and to his own ethnic identity. The nation currently referred to as “Sri Lanka,” located off the southern tip of India, was occupied by the Portuguese in the sixteenth century and the Dutch in the seventeenth century. England began acquiring territories on the island at the end of the eighteenth century and by 1815 the entire island had fallen under British rule. The nation did not gain independence from Britain until 1948. While the northern tip of the island is only 30 miles from India, Ceylon was not officially part of the Raj. It operated as a separate Crown colony that British colonial discourses worked to position as disconnected and highly disparate from India. As Sujit Sivasundaram argues, “While Ceylon’s British rule shared many parallels with British India, this act of disconnection meant that it served as a different laboratory for forms of state-making, following a separate chronology and leaving a different legacy, for instance in relation to ethnic identities” (14). Historical accounts of the roots of ethnic tension in Sri Lanka have foregrounded the role that the implementation of a system of representation founded on Victorian racial theory played in substantializing ethnic difference during the nineteenth century. As Jonathan Spencer notes, “As Sri Lankans were gradually admitted to the higher levels of colonial government, it was assumed that each section of the population could only be effectively be represented by a person of the same ‘kind,’” initiating a new degree of attentiveness to ethnic distinctions (Spencer 8).[10] However, in the final decades of the nineteenth and the early decades of the twentieth century, prior to the economic crisis in the 1920s and 30s that exacerbated concerns on the parts of Sinhalese workers about Tamil “interlopers” (from both northern Ceylon and India), multiple societies and publications worked to reinforce a sense of transethnic Ceylonese nationalism. As Mark Ravinder Frost notes, “As early as 1878, for example, the Burgher-owned Ceylon Examiner (Colombo’s leading English-language newspaper of the day) advocated the dropping of distinct labels such as ‘Sinhalese,’ ‘Burgher’ and ‘Tamil’ and the adoption of the appellation ‘Ceylonese’ by all. In 1889, plans were laid in the city for the establishment of a joint Hindu-Buddhist college and around 1908 the De Silva Cosmopolitan Institute was founded to encourage social interaction, intellectual discussion and greater understanding between the country’s various ethnicities” (62). The Ceylon National Review’s cosmopolitan, transethnic vision of Ceylonese nationalism should be understood as a reflection of this political moment when multiple societies and periodicals were working to cultivate a sense of national unity that transcended ethnic divisions.

Coomaraswamy’s particular mode of cosmopolitan Ceylonese nationalism involved the integration of the principles of British socialist aestheticism with a strident critique of British imperialism. While the infection of Ceylon with Western forms of commercialism and industrialism troubled him deeply, he nevertheless insisted that principles drawn from the aestheticist tradition in England might point the way out of the crisis he perceived in colonized India and Ceylon. Coomaraswamy’s highly cosmopolitan approach to Ceylonese nationalism should be understood as result of his own hybridity. While he was born in Ceylon, he had returned to England with his mother Elizabeth at the age of two. His father, who was to follow his wife and child abroad to pursue a career in British politics, died on the day of his intended departure, and Elizabeth decided to stay in England and raise her son there. Ananda attended University College, London, where he studied geology, and, while conducting geological research in Barnstaple, he met a local woman named Ethel Partridge, whom he married. Allan Antliff speculates that he was most likely introduced to the thinking of William Morris by Ethel, whose brother was a craftsman at the Chipping Campden Guild of Handicraft, run by C. R. Ashbee.[11] Coomaraswamy was, as a result of his English education and his marriage to a woman with links to the British arts and crafts tradition, deeply conversant in British cultural discourses of the late-Victorian period. When he returned to Ceylon, he acknowledged his own hybridity and alienation from his Ceylonese heritage, while at the same stressing a deep sense of connectedness with Tamil culture. Addressing a Tamil audience in Jaffna in 1906, he begged forgiveness for his inability to speak Tamil and urged his listeners to believe that he nevertheless wished to be accepted as “one of [themselves]”: “When I came to Ceylon for the third time, nearly four years ago, I was still to all intents and purposes an Englishman, but while I have lost nothing of my affection for English literature and art, I have been reborn as a child of India, and have in some measure returned to the ancestral home as a child to its parents” (qtd. in Singam, “Why a Biography?” 5). Remaking himself as a “reborn child of India,” Coomaraswamy nevertheless reminded his listeners of his English past and his enthusiasm for English culture, casting himself as at once the offspring of the island and a product of English thinking.

William Morris was the most significant influence on Coomaraswamy’s thinking during this early phase of his career. He read widely within the aestheticist tradition, exhibiting an interest in its foundational influences, such as John Ruskin, and its early stages, such as the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, as well as the later phases of the British Arts and Crafts movement. He held a broad interest in the Pre-Raphaelites, celebrating, for example, Burne Jones’s critique of the concept of “dominant races” and arguing that he “almost alone amongst artists of the modern West seems to have understood art as we in India understand it,” but Morris in particular held the most sway over his approach to anticolonialism (The Deeper Meaning of the Struggle 6; The Aims of Indian Art 5). As a review of Coomaraswamy’s Netra Mangalya (1908) published in the Ceylon National Review notes, he was a “devoted follower” of Morris (241). Coomaraswamy engaged during the early phase of his career with numerous figures linked to the Arts and Crafts movement in England, such as Ashbee, Walter Crane, and Eric Gill, but it was Morris’s influence that was most clearly legible. Eric Schroeder, the Keeper of Islamic Art at Harvard’s Fogg Museum, described Coomaraswamy as “one of Morris’s people, he even looked it—the flowing hair, the old clothes” (qtd. in Lipsey 259). Critics writing on Coomaraswamy’s indebtedness to Morris have tended to argue that the significance of the influence cannot be overstated. Roger Lipsey, for example, argues that the “relation between the two men does not fit into the sequence of Coomaraswamy’s life as just another element: it is the precondition of the sequence, a first orientation that provided direction throughout” (259). According to Larry D. Lutchmansingh, it may, in fact, be argued that “among those who claimed intellectual allegiance to Morris, it was Coomaraswamy who most effectively deployed his critique against modernity” and “extended Morris’s principles of judgment to twentieth-century conditions and gave them a non-Eurocentric inflection” (35). Coomaraswamy communicates clearly his devotion to Morris in the foreword to his Mediaeval Sinhalese Art, in which he notes with pride that “this book has been printed by hand, upon the press used by William Morris for printing the Kelmscott Chaucer” (ix). “I cannot help seeing in these very facts,” he asserts, “an illustration of the way in which the East and West may come together to be united in an endeavour to restore that true Art of Living which has for so long has been neglected by humanity” (ix). The book’s mode of production spoke materially to Coomaraswamy’s cosmopolitan desire to synthesize Morris’s radicalism and his own utopian anticolonialism and thereby engender a Ceylonese future akin to News from Nowhere, the return of the weaver to his loom, the craftsman to his tools, and the ploughman to his songs.

Coomaraswamy began this interweaving of Morris’s thought with Ceylonese nationalism in the years preceding the publication of Mediaeval Sinhalese Art in early works, such as “Open Letter to the Kandyan Chiefs” (1905) and The Deeper Meaning of the Struggle (1907), and in the pages of the Ceylon National Review. In “Kandyan Art: What It Meant and How It Ended,” which appeared in the first issue of the periodical, he addresses the dissolution of traditional artistic practices in the Kandyan Provinces, quoting liberally (and often without citation) from Morris as he gazes back nostalgically to a Ceylonese past that looks remarkably like medieval England.[12] The Kandyan artists of the past integrated use and ornament, much like Morris’s craftsman who, as described in “Useful Work v. Useless Toil” (1884), “fashioned the thing he had under his hand, ornamented it so naturally and so entirely without conscious effort that it is often difficult to distinguish where the mere utilitarian part of his work ended and the ornamental began” (qtd. in “Kandyan Art” 2).[13] In decrying the manner in which “modern civilization” is hostile to the persistence of these ideal and pleasurable labor conditions, he also borrows extensively from Morris’s disciples, such as Walter Crane, quoting Crane’s statement in The Claims of Decorative Art (1892) concerning the modern absence of “popular art—the art of the people, hand in hand with everyday handicraft, inseparable from life and use—that spontaneous art of the potter, the weaver, the carver, the mason, which our economical, commercial, industrial, competitive, capitalistic system has crushed out of existence” (qtd. in “Kandyan Art” 10).[14] To reinstate the conditions necessary for popular art to thrive would necessitate “great and fundamental changes in the organization of society, and a right understanding of the greatest of all arts, the art of living” (“Kandyan Art” 11). This would constitute a rejection of “Western civilization” and its approach to labor (11). Morris’s arguments are remade here into a declaration of war against the imperial expansion of capitalist principles into Ceylon. However, the fundamental changes for which Coomaraswamy calls would not result in a simple return to the conditions preceding the ceding of the island to the British. Coomaraswamy’s utopian Ceylonese future exceeds in beauty even the Kandyan past, with art “nobler and greater than any born in the ancient days of political, or the modern and more fatal ones of industrial slavery” (11). A revolutionary return to a concern with the art of living would result in the evolution of Ceylonese culture, freeing it from the hierarchical forms of exploitation that had governed the distant past and the dehumanizing labor practices of the present. The “great new art” of Ceylon will, Coomaraswamy concludes, “spring from [the] ashes” of its past, a final statement that seems to indicate that some destruction, some burning and devastation, will be necessary to create the conditions for this great new art to grow (12). In “Kandyan Art,” his shot across the bow, Coomaraswamy announces himself as one unafraid to implement radical rhetoric in the critique of capitalism and empire, and he indicates that British socialist aestheticism will operate as the key foundation for his mode of anticolonial thinking.

This braiding together of the rhetoric of British socialist aestheticism and anticolonial resistance became a fixture of the periodical in its early years. Coomaraswamy published his 17 April 1906 presidential address to the Ceylon Social Reform Society, “Anglicisation of the East,” in the second issue of the Ceylon National Review. In this address, he derides the “intellectual and moral damage,” as opposed to economic and political effects, accompanying the occupation of India and Ceylon, the “[sterilization of] the minds of the Ceylon or Indian youth,” and the “destruction—for no other word suffices—of popular art in India” (“Anglicisation of the East” 181, 184, 186). Like “Kandyan Art,” the address simmers with rage at the “injury to the beauty of the earth which in one way or another has been involved in the progress of the ‘Industrial Revolution.’” (“Of the effects of Western civilization on Eastern art it is difficult,” Coomaraswamy notes, “to speak with patience” [186].) Again, he turns to Morris, acknowledging that his predecessor’s critique of capitalism has global relevance by citing his statement that “so far reaching is this curse of commercial war that no country is safe from its ravages; the traditions of a thousand years fall before it in a month” (qtd. in Coomaraswamy, “Anglicisation of the East” 187).[15] Much as Morris’s socialism spoke in an aesthetic register, Coomaraswamy treats the problem of empire as an aesthetic one. Imperialism has, he asserts, made “the East” into a fundamentally uglier place. “Worst of all,” he argues, “the once infallible taste of the people themselves is now ruined, seemingly beyond all remedy; the ornaments and pictures now fashionable in Eastern homes are such that by comparison, the Berlin woolwork and wax flowers of early Victorian England seem almost beautiful” (187). The superior aesthetic instincts of India or Ceylon, when infected with the vulgarity of the West, wither and perish. “The inborn taste of an Indian or Ceylonese who is more or less Europeanised has,” he insists, “been entirely eradicated” (192). Colonization diseases and destroys the colonized’s sense of beauty, and this is posited as the key tragedy of imperial occupation.

The integration of anticolonial critique and socialist aestheticism performed within the pages of the Ceylon National Review meant that empire was frequently treated as an aesthetic problem, and not by Coomaraswamy alone. The editors chose to include in the periodical’s third issue a revised version of an 1893 essay on “The Artistic Aspect of Dress” by the Pre-Raphaelite painter Henry Holiday, first published in Algaia: The Journal of the Healthy and Artistic Dress Union.[16] Holiday had visited Ceylon as a member of the Royal Astronomical Society’s solar eclipse expedition in 1871, and the revisions to which he subjected the essay for inclusion in the Ceylon National Reviewspeak to his experiences in the country years prior. Drawing from this earlier perspective on colonized Ceylon, he seems somewhat less cynical about the complete dissolution of Eastern aesthetic standards, noting that “in the warm countries of the East which are favourable to beautiful dress, where the curse of machine-made civilization has not yet acquired despotic power, and where European systems of money-making have not dried up all sense of beauty, dress may now be seen full of grace and charm, healthful, comfortable and delightful to the eye” (291). He acknowledges, however, that the residents of Eastern nations have come increasingly to imitate the fashions of the West, a site where “mechanical progress has been seized upon by money-makers and devoted to sordid ends, and before the baneful energy of this greedy horde the arts of daily life have gone down, giving place to gloom, monotony, clumsy formlessness and all that is hateful to lovers of beauty (291). He bemoans the “incredible” fact that “races among whom beauty has flourished for so long and where it still exists should willfully shut their eyes to it and deliberately copy the vices of the West” (291-92). Holiday’s anticolonial fashion treatise harmonizes nicely with Coomaraswamy’s aesthetic critique of empire and speaks to the rich cross-pollination between the discourses of anticolonialism and socialist aestheticism in the early-twentieth century.

The framing of ethical and political problems in aesthetic terms extended to the treatment of vegetarianism in the Ceylon National Review. In an essay on “Vegetarianism in Ceylon” (1908), for example, Coomaraswamy, after arguing that the slaughter of animals for food contradicts the ideals of both Buddhism and Hinduism, notes, “There is another aspect of the question that weighs as much with me as any other. I mean the aesthetic aspect. There is no doubt that nearly everything connected with a meat diet is more or less ugly, from the slaughter-house to the ‘juicy beefsteak’ itself. The butcher’s shop is a repulsive sight. . . . Perhaps good taste has had something to do with its absence in the past.” (130). Here Coomaraswamy seems to be ventriloquizing Wilde rather than Morris as he speaks with withering disdain of the vulgarity of anything connected with the consumption of meat.[17] This argument is representative of the conflicted or cosmopolitan manner with which the Ceylon National Reviewapproached the topic of vegetarianism. While Coomaraswamy states that “abstinence from flesh is an ancient and almost essential element of the Indian view of life,” he also positions the rejection of the meat diet as a sophisticated and au courant import from the West (128). In a review of Ernest Crosby and Elisee Reclus’s The Meat Fetish (1905), for example, he preys upon his readers’ desire to remain in step with Western fashions, speculating that, after reading the reviewed work, “perhaps some of the of the Ceylonese who have adopted the eating of dead flesh along with other aspects of Western civilization will bethink themselves that they are a little behind the times and if they would be really up to date, should return to their former simple diet” (107). The periodical regularly featured reviews of British treatises on vegetarianism, such as Henry Salt’s The Logic of Vegetarianism (1899, 2nd ed. 1906), and reproduced passages from, for example, the Animal’s Guardian, a British monthly edited by the secretary of London Antivivisection Society, Sidney Trist, that ridiculed “corpse-eating” as a relic from the days “when our fathers wrote sermons about man’s place in Nature, and concluded that the Universe was nothing but his kitchen-garden” (“What Shall I Eat” 237). The editors of the Ceylon National Review strategically appealed to their readership’s wish both to preserve a fundamentally Ceylonese consciousness and to remain abreast of contemporary developments in London. In addition, in linking themselves to British practitioners of vegetarianism, Ceylonese nationalists put themselves in conversation with the broader forms of radicalism and dissent with which the practice was associated in England. As Leela Gandhi has argued in her discussion of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi’s engagement with English vegetarian circles, Victorian zoophilia should be understood as a resistance to modern forms of power based in “a pathological form of nonrelationality, achieving its most pernicious dimension in the sequestering logic of imperialism” (86). Thus Gandhi’s participation in British discourses of vegetarianism could at once function as a confirmation of traditional Hindu ideals and a cosmopolitan communion with English bohemian circles that linked animal liberation, socialism, anarchism, and anticolonialism. Like Gandhi, Coomaraswamy and his co-editors seemed to find in British vegetarian theory a transnational and highly modern validation of traditional Buddhist and Hindu principles and in British vegetarian theorists a broader anticolonial community.[18]

Theosophy similarly served as a cosmopolitan source of vitalizing energy for Indian and Ceylonese nationalist consciousness in the early-twentieth century, and the Ceylon National Review’s engagement with the movement mimics its turn to British vegetarian discourse, finding in imported forms of occultism access to fashionable modes of bohemianism as well as pleasing evidence of the superiority of Ceylonese traditions. As Mark Bevir argues in his discussion of “Theosophy as a Political Movement,” while the Theosophy Society described itself as “unconcerned about politics,” the movement was highly “entangled with the nationalist struggle” in India in the early-twentieth century (159). Due to its identification of “India as the source of ancient wisdom,” Theosophy was, as Bevir’s work indicates, “an integral part of a wider movement of neo-Hinduism, and this neo-Hinduism helped to provide Indian nationalists with a legitimating ideology” (161, 160). Srinivas Aravamudan notes that the suggestion on the part of Theosophist doctrine that Indian individuals were “spiritually superior to their imperial masters was a public relations masterstroke that hastened the recruitment of native elites to the movement” (110). Theosophy, Bevir asserts, “helped to provide Indians . . . with a new confidence in the worth of their culture. It suggested that their past, their customs, their religion, and their way of life, were as good as, even better than, those of their Imperial rulers” (170). The movement played a similar role in Ceylon, in this case confirming the importance of the Buddhist tradition and providing material means for reinvigorating that tradition. The Theosophical Society held a marked presence on the executive committee and advisory council for the Ceylon Social Reform Society, and Coomaraswamy co-edited the Ceylon National Review with two of its members, Frank Lee Woodward (1871-1952) and W. A. de Silva. W. A. de Silva, the president of the Buddhist Theosophical Society, was a Ceylonese veterinary surgeon who turned to nationalist activism and was later elected as a member of the State Council of Ceylon. Woodward was an English Buddhist scholar who served as principal of the Mahinda Buddhist College in Galle, a school established by the Buddhist Theosophical Society in 1892. Woodward came to Theosophy through his friendship with the movement’s co-founder Henry Steel Olcott (1832-1907), who had formally converted to Buddhism on his arrival in Ceylon with Helena Blavatsky in 1880 and is often credited with contributing to the revival of Buddhism and Buddhist education on the island. On his passing, the Ceylon National Review honored Olcott as a “pioneer and reformer” who had worked to “encourage the revival of native arts and crafts, salutary national customs fallen into decay, the study of religion and pride in nationality” (“The Late Colonel H. S. Olcott” 73). The members of the Ceylon Social Reform Society clearly understood their relationship with Theosophy as a productive one that helped to facilitate the reemergence of traditional arts and faiths on the island.[19]

In November 1907, the Ceylon Social Reform Society welcomed the Theosophical Society’s new International President Annie Besant to Colombo and invited her to deliver a lecture on “National Reform: A Plea for a Return to the Simpler Eastern Life.” Her lecture, published in the February 1908 issue of the Ceylon National Review, indicates much about why the movement might have held appeal for cosmopolitan Ceylonese nationalists in the early-twentieth century. While she acknowledged that “blind antagonism to the foreigner” might not be the most productive stance for her listeners to occupy, she called them to exercise caution in their engagement with Western culture and to “make your own national characteristics the leading features of your civilization and only . . . accept from the foreign civilization that which can enrich your own without injuring it” (100). She encouraged them to let their “Sinhalese civilization . . . remain Eastern”: “Do not debase, but only enrich; do not denationalize, only increase the circle of your national thought. Then the contact will be useful and not death-bringing” (100-01). The careful and politically conscious transnationalism described by Besant resembles the artful repurposing of British socialist aestheticism practiced by Coomaraswamy. While Coomaraswamy became, later in his career, mistrustful of Theosophy due to his insistence on “the necessity of learning directly from the sources of religious knowledge,” the movement’s cosmopolitan integration of principles drawn from Eastern and Western faiths as well as its commitment to nationalist activity in colonized India served as an attractive model of anticolonial resistance founded in transnational cooperation (Lipsey 31).

During his time as president of the Ceylon Social Reform Society and editor of the Ceylon National Review, Coomaraswamy became increasingly interested in India and came more and more to believe that “Ceylon must realize her oneness with India” (Review of Swami Vivekananda 381). Sivasundaram has used the terms “islanding” and “partitioning” to describe British colonialism’s creation of Ceylon as “a separate state, with separate channels of accountability and a distinct idea of space” (29, 16). Coomaraswamy’s insistence that Ceylon should be understood as one with India can thus be understood as a rejoinder to this process of “islanding” the Ceylonese from India. When he stepped down from the presidency of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, he turned his attention more thoroughly to Indian art history and the campaign for Indian independence, traveling to India, where he became friendly with the Tagore family, and assisting William Rothenstein and Roger Fry in the foundation of the India Society in 1910. This early stage in his career, however, when he thought carefully about Ceylon and from within Ceylon deserves serious attention as a foundational moment in his formulation of a cosmopolitan and aesthetically inflected approach to anticolonialism. Under his leadership, the diverse membership of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, which included Tamil and Sinhalese authors and activists as well as British scholars and educators, and the complex dialogue taking place within the pages of the Ceylon National Review, which integrated the discourses of anticolonialism and socialist aestheticism and allowed British and Ceylonese vegetarians and Theosophists to speak in relation to one another, engendered a particularly rich and surprising form of Ceylonese nationalism. For scholars of Victorian studies, this discourse offers evidence of the striking ways in which Victorian forms of political and religious dissidence evolved and transformed as they were dispersed globally, remade by colonized subjects, and turned against the very empire from which they emanated.

Appendix

Notes

- I wish to thank Anna Maria Jones, Kathy Psomiades, and the anonymous readers at BRANCH for their invaluable feedback on this essay. This research was made possible by a Research Support Grant from the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

- According to James Crouch, the Society was “inaugurated on 22 April 1905 at Musaeus College, Colombo” (61).

- Along with its emphasis on Ceylonese craft, the society also encouraged the study of Pali and Sanskrit literature as well as Sinhalese and Tamil literature and the protection of ancient buildings and works of art. While the Society under Coomaraswamy’s direction focused primarily on arts and culture, when Donald Obeysekare became president on May 2, 1908, he announced in his presidential address that the revival of traditional medicine in Ceylon would be his focus. See Abeyrathne 35. In his discussion of the Ceylon National Review, Michael Powell argues that the Ceylon Social Reform Society was “no revolutionary group” and “viewed with caution political reform that moved beyond the capacity of the nation to absorb change” (267). However, I would argue that, though the very name of the society certainly stresses a reform-based approach to political change, Coomaraswamy’s critique of existing conditions in Ceylon should be understood as a form of resistance to British imperialism. Nevertheless, it should also be acknowledged that, as Dohra Ahmad has argued, in works such as Art and Swadeshi (1912), Coomaraswamy articulated a form of anticolonial thinking that privileged cultural freedom over “its political counterpart” (83).

- Similar copy concerning the periodical’s mission and contents followed the table of contents in each issue of the Ceylon National Review. The inaugural issue also announced that the periodical would be published at intervals of about six months at a price of Rs 1.25 (or 60 cents for members of the society) locally and 2/- in England. The Ceylon National Review’s actual publication schedule was somewhat irregular. Issues appeared in January 1906, July 1906, January 1907, July 1907, February 1908, May 1908, August 1908, June 1909, March 1910, and January 1911. In 1908, the local price was reduced to Rs 1.00. Coomaraswamy insisted, while speaking in Jaffna in 1906, that it was crucial for the periodical to “secure a large circulation” (qtd. in Singam, “Ananda Coomaraswamy in Ceylon” 81). The Ceylon National Review did not, however, disclose its circulation numbers in its pages.

- “Ceylon” was the British name for the nation currently referred to as “Sri Lanka.” The name was derived from its Portuguese name, “Ceylao.” In 1972, a new republican constitution renamed the nation Sri Lanka. The mission of the Ceylon National Review was embedded within and responded to a specific set of historical conditions that are tied up with British colonization of the island, and the members of the Ceylon Social Reform Society were theorizing resistance to colonialism more than sixty years before the modern nation of Sri Lanka had been established. In this essay, because I am focusing on a historical moment that predates independence and the renaming of the nation and in order to foreground the Ceylon National Review’s situation within that moment, I will refer to the country as “Ceylon” rather than “Sri Lanka.”

- According to James Crouch, Coomaraswamy had visited Ceylon prior to his appointment as director of the Mineralogical Survey of Ceylon. See Crouch 54.

- For a discussion of Coomaraswamy’s influence on British modernism, see Chapter Two, “An Indian Temple on the Strand: Charles Holden, Ananda Coomarasway, and London’s First Modernist Sculptures,” in Rupert Arrowsmith’s Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde.

- Coomaraswamy returned to England in early 1907. Notes from the May 2, 1908 annual meeting of the Ceylon Social Reform Society, printed in the August 1908 issue of the Ceylon National Review, indicate that he wrote to the society from England encouraging them to elect a new president who resided locally.

- For an overview of recent work on the concept of “subaltern cosmopolitanism,” see Minhao Zeng’s “Subaltern Cosmopolitanism: Concept and Approaches.”

- Spencer notes that “the problem of the social variety” in Ceylon was dealt with by engaging in a process of racial categorization: “The result was that by the end of the nineteenth century a large number of distinct ‘races’ were recognized by the authorities in colonial Sri Lanka” (27).

- See Antiff 128.

- As Robin Jones argues, in privileging the arts and crafts of Kandy, Coomaraswamy reinscribes “a romanticized notion of that region’s resistance to colonial rule and the troubling hybridization evident in much of the material culture of the coastal regions of the island” (384). (Kandy was the last region to fall to the British.) Jones argues, drawing on the work of architectural historian Swati Chattopadhyay, that the British administration in Ceylon favored “authentic” Kandyan art because it did not exhibit the disconcerting signs of hybridity and extended colonial contact on display in the crafts of the Low Country or coastal belt. Such hybridity could be troubling to British audiences, according to Chattopadhyay, “not just [because] it implied a changing native culture but that it also indicated the impossibility of generating a sovereign British existence untouched by native culture” (qtd. in Jones 387). Jones traces the British taste for “authentic” Ceylonese, or Kandyan, art in the nineteenth century both on the island, as tourists on Asiatic “Grand Tours” visited the Kandyan Art Association, and at events in England, such as the “India and Ceylon Exhibition” in London in 1896, and argues that the process of preserving traditional Kandyan crafts should be understood as problematic “because it was largely the British who were engaged in the preservation and documentation of local architectural and craft traditions” (400). Coomaraswamy’s work should, however, I would argue, be understood as operating in a disparate manner due to his critical relationship to British colonialism.

- “Useful Work versus Useless Toil” was published as a Socialist League pamphlet in 1885 and republished in Signs of Change in 1888, where this passage appeared on p. 164.

- This passage appeared on p. 127 of the 1892 edition of Crane’s The Claims of Decorative Art.

- This passage is drawn from Morris’s “How We Live and How We Might Live,” which was published in the Commonweal in 1887 in two installments. This passage appeared on p. 178 of the first installment.

- The essay first appeared in Algaia in 1893. The passages cited here did not appear in the original version of the essay, and all citations refer to the revised essay published in the Ceylon National Review in 1907.

- While Coomaraswamy’s tone here is Wildean, Wilde himself did not share his reverence for vegetarianism. He did, however, as Leela Gandhi argues, note the extent to which the practice was often bound up with broader forms of “noncomformist” and radical political thinking during the period (Gandhi 76). In a November 12, 1887 letter to Violet Fane in response to her proposal to write an essay on the topic for Woman’s World, Wilde wrote, “It is strange that the most violent republicans I know are all vegetarians: brussels sprouts seem to make people bloodthirsty, and those who live on lentils and artichokes are always calling for the gore of the aristocracy and for the severed heads of kings” (qtd. in Gandhi 77).

- It is worth noting that the privileging of vegetarianism in the pages of the Ceylon National Review implicitly links Ceylonese identity to a set of practices that is more in line with Buddhist and Hindu faiths than with Christianity or Islam. This is a reflection of the periodical’s tendency to focus primarily on the Sinhalese and Tamil populations of Ceylon. While the periodical framed its project around the concept of unification, in its focus on Sinhalese and Tamil culture, it could also be seen as subtly marginalizing certain populations on the island, including Dutch Burghers and Muslims. However, as Michael Powell notes, the selection of vice presidents for the Ceylon Social Reform Society, which included James Pieris, a Christian; Abdul Rahiman, a Muslim; and Gate Mudaliyar E. R. Gooneratne, a Buddhist, does reflect an attempt to engage in a “careful [balancing] of . . . interests” on the part of the Society (267).

- Though the treatment of Theosophy within the pages of the Ceylon National Review was favorable, as Joy Dixon notes, “the accounts theosophists provided of Asian religions were much criticized, both by scholars and by orthodox Hindus and Buddhists” (4). Coomaraswamy entered into debate with critics of Theosophy’s integration of multiple religious traditions, who questioned Theosohy’s right to “support Buddhism in Ceylon, Hinduism in India and Christianity in Europe and America,” in the pages of the Ceylon Observer (“The Theosophical Society” 371-72). Coomaraswamy insisted that Theosophists simply recognized that “it is absurd to claim that any one religion embodies the whole truth,” but the editor responded to his contribution by arguing that the Theosophists were dishonest and posed as primarily Buddhist or Hindu depending on their location in order to more effectively extract financial contributions from the people of India and Ceylon (372). Dixon argues that “the inequalities of power that structured exchanges in the colonial context mark theosophy’s syncretizing impulse as a distinctively colonial one. Theosophists claimed to uncover the esoteric truths of traditions from beneath their exoteric accretions, to rescue a form of knowledge that had fallen into degraded forms in India. Theosophy was therefore a kind of middle-brow orientalism (in Edward Said’s sense), which reinscribed divisions between eastern mysticism and western science” (11). While the members of the Ceylon Social Reform Society were receptive to Theosophy, approval of Theosophy certainly was not unanimous in early twentieth-century Ceylon, and critics of the faith often expressed suspicion of Theosophy’s Orientalist tendencies.

Works Cited

- Abeyrathne, Rathnayake. “The Role Played by the Ceylon Reformed Society and the Oriental Medical Science Fund in the Revival of Traditional Medicine in Ceylon/Sri Lanka.” Social Affairs: A Journal for the Social Sciences, vol. 1, no. 2, 2015, pp. 33-46.

- Ahmad, Dohra. Landscapes of Hope: Anti-Colonial Utopianism in America. Oxford UP, 2009.

- Antiff, Allan. Anarchist Modernism: Art, Politics, and the First American Avant-Garde. U of Chicago P, 2001.

- Aravamudan, Srinivas. Guru English: South Asian Religion in a Cosmopolitan Language. Princeton UP, 2006.

- Arrowsmith, Rupert. Modernism and the Museum: Asian, African, and Pacific Art and the London Avant-Garde. Oxford UP, 2011.

- Besant, Annie. “National Reform: A Plea for a Return to the Simpler Eastern Life.” Ceylon National Review, no. 5, February 1908, pp. 97-110.

- Bevir, Mark. “Theosophy as a Political Movement.” Gurus and Their Followers: New Religious Reform Movements in Colonial India, edited by Antony R. H. Copley, Oxford UP, 2000, pp. 159-79.

- Boehmner, Elleke. Empire, the National, and the Postcolonial, 1890-1920. Oxford UP, 2002.

- “Ceylon Social Reform Society: Manifesto.” Ceylon National Review, no. 1, January 1906, pp. ii-iii.

- Coomaraswamy, Ananda. The Aims of Indian Art. Broad Campden: Essex House Press, 1908.

- —–. “The Anglicisation of the East.” Ceylon National Review, no. 2, July 1906, pp. 181-95.

- —–. The Deeper Meaning of the Struggle. Essex House Press, 1907.

- —–. “Kandyan Art: What It Meant and How It Ended.” Ceylon National Review, no. 1, January 1906, pp. 1-12.

- —–. Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. Essex House Press, 1908.

- —–. Review of Swami Vivekananda, a Collection of His Speeches and Writings, by Swami Vivekananda, Ceylon National Review, no. 3, January 1907, pp. 380-81.

- —–. Review of The Meat Fetish: Two Essays on Vegetarianism, by Ernest Crosby and Elisee Reclus. Ceylon National Review, no. 1, January 1906, 106-07.

- —–. “The Theosophical Society.” Ceylon Observer, March 2, 1906, pp. 371-72.

- —–. “Vegetarianism in Ceylon.” Ceylon National Review, no. 5, February 1908, 125-31.

- Crane, Walter. The Claims of Decorative Art. Lawrence and Bullen, 1892.

- Crouch, James. “Ananda Coomaraswamy in Ceylon: A Bibliography.” Ceylon Journal of Social and Historical Studies, vol. 3, no. 2, 1973, pp. 54-56.

- Dixon, Joy. Divine Feminine: Theosophy and Feminism in England. Johns Hopkins UP, 2001.

- Frost, Mark Ravinder. “Cosmopolitan Fragments from a Splintered Isle: ‘Ceylonese’ Nationalism in Late-Colonial Sri Lanka.” Ethnicities, Diasporas and “Grounded”

- Cosmopolitanisms in Asia, Asia Research Institute, 2004.

- Gandhi, Leela. Affective Communities: Anticolonial Thought, Fin-de-Siècle Radicalism, and the Politics of Friendship. Duke UP, 2006.

- Holiday, Henry. “The Artistic Aspect of Dress.” Aglaia, no. 1, July 1893, pp. 13-30.

- —–. “The Artistic Aspect of Dress.” Ceylon National Review, no. 3, January 1907, 285-96.

- Jones, Robin. “British Interventions in the Traditional Crafts of Ceylon (Sri Lanka), c. 1850-1930.” The Journal of Modern Craft, vol. 1, issue 3, 2008, pp. 383-404.

- “The Late Colonel H. S. Olcott.” Ceylon National Review, no. 4, July 1907, 73-74.

- Lipsey, Roger. Coomaraswamy: His Life and Work, Volume III. Princeton UP, 1977.

- Lutchmansingh, Larry. “Ananda Coomaraswamy and William Morris.” Journal of William Morris Studies, vol. 9, no. 1, 1980, pp. 35-42.

- Morris, William. “How We Live and How We Might Live.” Commonweal, vol. 3, no. 73, June 4, 1887, pp. 177-78.

- —–. Signs of Change: Seven Lectures Delivered on Various Occasions. Reeves and Turner, 1888.

- Powell, Michael. Cultural and Religious Themes in the Life of F. L. Woodward. Dissertation, University of Tasmania, 1999.

- Review of Netra Mangalya by Ananda Coomaraswamy. Ceylon National Review, no. 6, May 1908, p. 241.

- Singam, S. Durai Raja. “Ananda Coomaraswamy in Ceylon.” Ananda Coomaraswamy—The Bridge Builder: A Study of a Scholar-Colossus, edited by S. Durai Raja Singam, Khee Meng, 1977, pp. 1-94.

- —-. “Why a Biography? Coomaraswamy on Coomaraswamy.” Ananda Coomaraswamy—The Bridge Builder: A Study of a Scholar-Colossus, edited by S. Durai Raja Singam, Khee Meng, 1977, pp. 1-24.

- Sivasundaram, Sujit. Islanded: Britain, Sri Lanka, and the Bounds of an Indian Ocean Colony. U of Chicago P, 2013.

- Spencer, Jonathan. Sri Lanka: History and the Roots of the Conflict. Routledge, 1990.

- “What Shall I Eat.” Ceylon National Review, no. 6, May 1908, pp. 236-37.

- Zeng, Minhao. “Subaltern Cosmopolitanism: Concept and Approaches.” The Sociological Review, vol. 62, no. 1, 2014, pp. 137-48.

Originally published by BRANCH Collective (September 2018) under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported license.