Americans who consume partisan media tend to express less accurate beliefs about a host of politically charged topics.

By Dr. R. Kelly Garrett

Professor and Director, School of Communication

The Ohio State University

By Dr. Jacob A. Long

Assistant Professor of Communication

University of South Carolina

By Dr. Min Seon Jeong

Visiting Assistant Professor of Communication

Pepperdine Seaver College

Abstract

This article provides evidence that affective polarization is an important mechanism linking conservative media use to political misperceptions. Partisan media’s potential to polarize is well documented, and there are numerous ways in which hostility toward political opponents might promote the endorsement of inaccurate beliefs. We test this mediated model using data collected via nationally representative surveys conducted during two recent U.S. presidential elections. Fixed effects regression models using three-wave panel data collected in 2012 provide evidence that conservative media exposure contributes to more polarized feelings toward major-party presidential candidates, and this growing favorability gap is associated with misperceptions critical of the Democrats. Further, these effects are more pronounced among Republicans than among Democrats. Cross-sectional analyses using data collected in 2016 provide additional evidence of the mediated relationship. The theoretical and real-world significance of these results are discussed.

Introduction

Americans who consume partisan media tend to express less accurate beliefs about a host of politically charged topics—from climate change to the birthplace of President Obama—than those who rely on less partisan sources (e.g., Feldman, Myers, Hmielowski, & Leiserowitz, 2014; PublicMind Poll, 2012). Online or off, politically slanted sources lead individuals to endorse falsehoods favoring the party with which the outlets are commonly associated. Although differences in the accuracy or amount of information provided by partisan outlets may help to explain this pattern (e.g., Feldman, Maibach, Roser-Renouf, & Leiserowitz, 2012), other explanations are necessary. Americans’ news diets, while not perfectly balanced, are far from insular (Bakshy, Messing, & Adamic, 2015; Flaxman, Goel, & Rao, 2016; Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2011), making widespread isolation from accurate information implausible. Furthermore, online partisan news exposure shapes beliefs even when consumers are familiar with evidence reported by less biased sources (Garrett, Weeks, & Neo, 2016).

We suggest that affective polarization plays a critical role in this process. Partisan media exposure promotes positive feelings toward members of the political ingroup and negative feelings toward the outgroup (Lelkes, Sood, & Iyengar, 2017; Levendusky, 2013), and we argue that these polarized emotions can help to explain inaccurate beliefs. As individuals grow increasingly hostile to those with whom they disagree, they become more likely to endorse misperceptions consistent with their own political worldview. Holding accurate beliefs about important issues is key to effective decision making. Individuals’ ability to accumulate accurate evidence—and to use this evidence to arrive at well-informed beliefs—is a critical step in forming candidate preferences, evaluating policy options, and choosing how to act (Delli Carpini & Keeter, 1996). When individuals ignore or misinterpret relevant evidence, arriving at beliefs that are compatible with their worldview but which are inconsistent with (most) empirical evidence and (most) expert interpretations, decision making is more likely to be flawed (Kuklinski, Quirk, Jerit, Schwieder, & Rich, 2000).1 In a democracy, the ability to weigh the facts and arrive at informed decisions is fundamental to society’s wellbeing. Lacking this ability, citizens are bound to make choices leading to preventable harm.

Although numerous studies have examined the antecedents of affective polarization, studies of its consequences are less common. If we are correct about this mechanism for explaining Americans’ political misperceptions, this would represent a socially significant harm of affective polarization. Scholars have already noted that the increasing animosity Americans feel towards those with whom they disagree makes compromise and joint problem solving more difficult (Iyengar & Westwood, 2014). The threat described here could exacerbate this problem. Even if individuals are willing to consider compromises in order to solve important social problems, they may not be able to agree about which problems require addressing or which solutions will work.

We used representative survey data collected in the 2012 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections to test whether affective polarization mediates the relationship between partisan media use and misperceptions. Fixed effects regression models, using three-wave panel data from 2012, afforded a robust test of our causal claims, while two waves of data from 2016 provided the opportunity for a partial replication with a different sample and improved operationalizations of key variables. We turn next to the theoretical foundations of our predictions.

Partisan Media and Misperceptions

There is ample evidence that news media shape people’s understandings of political reality. News exposure is a key component of political learning, tending to promote awareness and understanding (Elenbaas, de Vreese, Schuck, & Boomgaarden, 2014; Eveland, 2001). These benefits do not necessarily accumulate uniformly: individuals’ political biases color how they interpret events in the news (Jerit & Barabas, 2012; Lenz, 2009). Partisan media, however, are unique: use of partisan news outlets has been shown to systematically promote misperceptions that are consistent with the interests of the associated party. For instance, those who get their news from Fox News are more skeptical of climate change science, regardless of their political predispositions (Feldman, 2011). Similarly, the more individuals rely on liberal outlets, the more likely they are to endorse falsehoods about a Republican candidate (Garrett et al., 2016). The relationship between partisan media exposure and endorsing factually inaccurate statements has been shown repeatedly (e.g., Meirick, 2013; PublicMind Poll, 2012).

Online news plays a defining role in the contemporary news environment. The Internet affords individuals more control over their information exposure, and more opportunity to seek out politically extreme content (Stroud, 2011). At the same time, gatekeepers have less influence over what is published and shared, thanks to the falling costs of publication and of producing visually appealing content (Katz, 1998). It has long been speculated that such an environment would foster misperceptions (Ayres, 1999; Sunstein, 2009).

Many of these concerns were realized when, during the 2016 election, news stories with no basis in political reality were shared extensively via social media (Silverman, 2016; also see Guess, Nagler, & Tucker, 2019). The rise of so-called “fake news” represents the most obvious way that politically biased news coverage can lead individuals to endorse falsehoods. News organizations can also promote misperceptions by distorting available evidence. The more individuals rely on sources that misrepresent the facts, the more likely they are to internalize this information (Eveland & Cooper, 2013), and the more believable it will seem (DiFonzo, Beckstead, Stupak, & Walders, 2016; also see Zajonc, 1968).

Although the selective presentation of facts may help to explain the influence that partisan outlets have on audience beliefs, it is unlikely to be the sole, or even primary, explanation. Most Americans’ online news diets are diverse, and include a considerable amount of attitude-inconsistent information (Bakshy et al., 2015; Flaxman et al., 2016; Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2011), so even if an outlet misrepresents the evidence, its users are likely to encounter claims to the contrary elsewhere. Furthermore, exposure to partisan media has an influence on beliefs that goes beyond what individuals know about relevant evidence, promoting the endorsement of ideas contradicted by this evidence (Garrett et al., 2016). Thus, media misrepresentations are only a part of the story.

Affective Polarization as Mediator

We argue that affective polarization is an important mediator linking partisan media exposure and misperceptions. Iyengar, Sood, and Lelkes (2012) proposed affective polarization as an alternative to polarization based on one’s political position. Partisans’ feelings toward their political opponents have grown increasingly negative over the past several decades, and Iyengar and colleagues (2012) demonstrated that this is not easily explained by differences in policy preferences; instead, they argue that media campaigns are largely to blame. Online and off, conservative news media are well known for their use of ad hominem attacks on Democratic politicians and their scathing criticisms of liberal policy positions (Jamieson & Cappella, 2008). Partisan media outlets on both sides have been described as engaging in outrage discourse: promoting hostility and disdain for those on the other side (Sobieraj & Berry, 2011). The more individuals rely on partisan outlets, the greater their dislike of the outgroup vis-a-vis the ingroup (Hmielowski, Beam, & Hutchens, 2015; Lelkes et al., 2017; Levendusky, 2013). Affective polarization could promote the endorsement of falsehoods about candidates from an opposed party by altering both message processing and the incentives shaping self-expression.

There are several reasons to expect that more polarized feelings toward political groups alters the processing of information about candidates. First, although attitudes have both affective and cognitive components (Crites, Fabrigar, & Petty, 1994; Haddock, Zanna, & Esses, 1993), affect is typically more accessible (Verplanken, Hofstee, & Janssen, 1998). There is growing evidence that affective responses influence all political judgements, and some scholars argue that political reasoning is, in reality, the post hoc rationalization of emotional responses (Lodge & Taber, 2013; and see Redlawsk, 2002). In this view, unconsciously triggered affective reactions associated with the subject of a (false) claim color the cognitions that come to mind when the claim is considered. The more polarized partisans’ affective responses toward opposing candidates are, the more influence these feelings are likely to have on information evaluations. Hostility, anger, and distrust toward a candidate and his or her allies will make individuals more receptive to claims that reflect poorly on the candidate.

Affect influences the processing of political information in other ways, too. Anger, in particular, promotes partisan bias, making individuals uniquely susceptible to ingroup-affirming misinformation (Weeks, 2015). More generally, emotional responses facilitate illogical processing, especially when the feelings are attributed to the target (Pham, 2007). To the extent that affective polarization is associated with anger or hostility directed at the opposition, partisans may be more willing to accept unsupported or poorly reasoned criticisms of opponents.

Affective biases can be amplified by group dynamics. The earliest work on affective polarization drew on social identity theory, arguing that exposure to political campaigns heightens partisan identity salience, thereby promoting inter-group prejudice (Iyengar et al., 2012). When coupled with deindividuation, which is commonplace online, social identity salience also contributes to increased compliance with social norms, and a greater willingness to endorse negative stereotyping of the outgroup (Reicher, Spears, & Postmes, 1995), both of which could promote misperceptions. Finally, there is evidence that individuals sometimes endorse falsehoods strategically, either as a form of party cheerleading (Bullock, Gerber, Hill, & Huber, 2015; Prior, Sood, & Khanna, 2015) or as a means of social-identity protection (Kahan, 2013). Affective polarization is likely to encourage both these behaviors: the more unfavorable the attitude toward the outgroup, the more the individual will want to promote the ingroup, and to reinforce his or her position within it. In sum, we predicted that:

H1: Partisan online media will indirectly promote misperceptions about outlet-opposed political candidates via affective polarization.

Further, we expected that the indirect effects of partisan media use on misperceptions would be moderated by party affiliation. To the extent that partisan media are engaging in tribal politics—building up their ingroup while denigrating the outgroup—audiences that share an outlet’s political orientation—who belong to the ingroup—are more likely to be polarized by its messages. For instance, Republicans are more likely to be swayed than Democrats by the negative characterizations of Democratic candidates commonly presented on conservative outlets.

H2: The indirect effect of partisan media use on misperceptions will be stronger when the user’s party affiliation matches the outlet’s political orientation.

The extant literature did not, however, lead us to a strong conclusion about the influence of partisan media use on those who identify as Independents. Choosing not to affiliate with either of the two major U.S. political parties could mean that Independents are less swayed by messages meant to rally major-party supporters. Alternatively, it could be that the attitudes and beliefs of members of the major parties are more firmly entrenched, which would suggest that Independents are more prone to media influences. Given this uncertainty, we posed a question:

RQ1: How does the indirect effect of partisan media use on misperceptions among Independents compare to its indirect effect among those who share the outlets’ political orientation?

Methods

We used panel data collected in two recent U.S. presidential elections to test our predictions. The first test used a three-wave panel design. Analyzed with fixed effects regression models, these data provided complete protection against the influence of stable, unmeasured, individual differences, increasing our confidence in the causal model proposed. The second test only used two waves of data—a limitation—but it also introduced improved measures of affective polarization and media use, and it focused on misperceptions that were more comparable across the two major parties than those used in the first study. Replication across two elections with different candidates, different misperceptions, and improved measures of key predictors, is an important aspect of this work.

Data

The surveys were administered during the 2012 and 2016 U.S. presidential elections by the GfK Group. The company’s KnowledgePanel was a probability-based online panel that was recruited with address-based sampling that was designed to be representative of the U.S. population (GfK Group, 2016). The company provided non-Internet households with netbooks and Internet service. Selected panelists were invited to participate in surveys via email, and were rewarded with participation points that could be redeemed for a variety of prizes. To improve cooperation rates in Waves 2 and 3, participants were offered additional incentives worth approximately $5. The datasets also include weights computed using the latest supplement of the current population survey.

In 2012, the baseline survey was conducted from 14 July to 7 August 2012, with 1004 respondents, followed by Wave 2, conducted from 7 September to 3 October, with 782 returning participants, and Wave 3, conducted from 8–20 November, with 652 respondents (83.4% retention from Wave 2, 64.9% from baseline). In 2016, the baseline survey was conducted from 29 July to 11 August, with 949 respondents, followed by Wave 2, conducted from 14–22 September, with 763 returning participants, and Wave 3 from 9–14 November, with 625 respondents (82% retention from Wave 2, 66% from baseline).

Respondents’ demographics indicated representativeness and diversity in regards to age (2012: M = 49.68, SD = 16.39; 2016: M = 49.59, SD = 17.73), gender (female 2012/2016: 52.3/52.2%), education (2012/2016: 34.2/33.6% Bachelor’s degree or higher; 90.3/91.3% high school or higher), income (2012/2016: median: $60,000–74,999), race (2012/2016: 77.0/75.2% White, 7.7/7.2% Black, 8.7/10.6% Hispanic, and 6.6/7.0% Others), political party affiliation (2012/2016: 46.1/41.1% Democrat or Democrat-leaning, 20.4/2.2% Independent, 33.5/38.7% Republican or Republican-leaning), and ideology (2012/2016: 30.4/29.0% liberal, 33.0/33.7% moderate, 36.7/37.3% conservative).

Analytic Approach

We analyzed the 2012 data using fixed effects regression models, which assessed within-respondent changes over the course of the election. This approach is widely recognized as a powerful tool for analyzing panel data (Allison, 2009; Halaby, 2004).2 A core strength of fixed effects modeling is its robustness to confounding. Each respondent is compared to himself or herself in other waves, meaning that there is no risk that observed effects are the product of stable individual characteristics. We estimated these fixed effects models using ordinary least squares regression (OLS) on the person–mean centered variables (see Allison, 2009) with cluster-robust standard error calculations using the individual and wave as clusters (Thompson, 2011), calculated via the sandwich R package (Berger, Graham, & Zeileis, 2017; Zeileis, 2004). We tested mediation models via the mediation package for R (Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele, & Imai, 2014), using quasi-Bayesian confidence intervals (King, Tomz, & Wittenberg, 2000) based on 10,000 simulations. In 2016, the binary outcome was only measured in the final wave, leading us to use a conventional logit regression with predictors that were measured in Wave 2, along with controls, to account for individual differences. We again used the mediation package to estimate indirect effects.

In all regression models that have misperceptions as the outcome, we included an interaction term between the predictor (partisan media) and mediator (affective polarization). Although this interaction was not substantively interesting, omitting the term could have biased results in unpredictable ways (Imai, Keele, & Tingley, 2010; Judd & Kenny, 1981). We used hot-deck imputation via the simputation R package (van der Loo, 2017), which was designed to replace a missing value “with the value of a similar ‘donor’ in the dataset that matches the ‘donee’ in researcher-determined categories” (Myers, 2011, p. 303). The deck variables we used were income, education, and gender. Finally, we did not use sample weights in these analyses. The statistical test described by Pfeffermann and Sverchkov (1999) indicated the sampling weights were ignorable (i.e., not influential) in our analyses at an alpha threshold of .05. This test was implemented in the jtools R package (Long, 2019).

2012 U.S. Presidential Election Survey Measures

Political Misperception

Political misperception was measured by asking respondents to assess whether they thought each of several statements about the two candidates—Democrat Barack Obama and Republican Mitt Romney—was true or false (see Supporting Information Appendix A for wording of all questions used in these studies). The measure combined respondents’ beliefs about four issues for each candidate on topics related their religious beliefs and their political positions.3 Details about the statement selection process are included in Supporting Information Appendix B. Belief was measured in two stages. First, respondents indicated whether they had previously encountered information supporting or challenging the claim, and then they were asked whether they believed it.

Beliefs were recoded so that higher scores correspond to greater inaccuracy, from definitely false (1) to definitely true (5). As our theoretical interests centered on beliefs individuals held based on previously encountered information, we excluded those who were not familiar with the falsehood from these analyses (Wave 1: Obama M = 2.66 SD = 1.27, n who heard before = 594, Romney M = 3.40, SD = .95, n = 328; Wave 2: Obama M = 2.58, SD = 1.22, n = 601, Romney M = 3.21, SD = .98, n = 417; Wave 3: Obama: M = 2.57, SD = 1.24, n = 608, Romney M = 2.96, SD = 1.06, n = 450).4

Online Partisan Media

Respondents were asked a series of questions about the frequency with which they used partisan online news outlets to get information about the presidential candidates or the campaign during the prior month on a five-point scale from “never” (1) to “every day or almost every day” (5). Several types of outlets were listed, each of which was presented with examples drawn from prior scholarship (e.g., Gentzkow & Shapiro, 2011). An index of liberal media use combined responses to items asking about the use of major national news sites that were “frequently characterized as favoring liberal positions or Democratic candidates” and of politically liberal online news organizations or blogs (Wave 1: M = 1.57, SD = .91; Wave 2: M = 1.54, SD = .88; Wave 3: M = 1.58, SD = .92). The conservative media use index was based on a comparable pair of items (Wave 1: M = 1.48, SD = .84; Wave 2: M = 1.45, SD = .83; Wave 3: M = 1.50, SD = .87). Although we considered these to be indices rather than scales, the two items each had .55 and .54 correlations between one another, respectively, which corresponds to a Cronbach’s alpha of about .70.

Affective Polarization

Following Iyengar et al.’s (2012) operationalization, we measured affective polarization using favorability ratings of in- and out-party members. Specifically, respondents were asked to rate their feelings towards each candidate from 0 to 10, with higher values denoting greater favorability. A difference measure was constructed by subtracting individuals’ rating of Obama from their rating of Romney (−10 = very favorable to Obama, 0 = neutral, 10 = very favorable to Romney; Wave 1: M = −.77, SD = 6.22; Wave 2: M = −.93, SD = 6.62; Wave 3: M = −.81, SD = 6.85). Respondents who said they had not heard of either of the two candidates were dropped from the models.

Party Affiliation

Respondents were asked to indicate their party affiliation. Response options were (1) strong Democrat, (2) not very strong Democrat, (3) Independent, lean toward Democrat, (4) Independent (close to neither party), (5) Independent, lean toward Republican, (6) not very strong Republican, (7) strong Republican, or (8) something else. We constructed dummy variables representing Republicans, which were coded high when response options 5 through 7 were selected, and Independents, which were coded high when response options 4 or 8 were selected.

Control Variables

Fixed effects models effectively control for any stable between-respondent differences. However, we did include controls for two dynamic factors: general political knowledge (range = 0–4, M = 2.43, SD = 1.32), and panel wave, which allowed us to control for over-time trends in belief accuracy. Our decision to treat political knowledge as a time-varying factor in our analyses stemmed from the fact that it is commonly considered to be an outcome of news exposure. Because general political knowledge tends to be stable over time, we also ran the models without controlling for this factor. Results were substantively unchanged throughout (see Supporting Information Appendix E).

2016 U.S. Presidential Election Survey Measures

Political Misperceptions

The 2016 survey included a question about respondents’ candidate beliefs in Wave 3 that was ideally suited to this study. A month before the election, the U.S. intelligence community issued a statement indicating that Russia was behind cyberattacks targeting e-mail accounts associated with the Democratic National Committee and Clinton campaign officials. The statement did not, however, say anything about the Trump campaign colluding with Russia in these efforts. Indeed, it would be several years before the investigation into this question was complete. A key benefit of this issue is that it formed the basis for a pair of symmetrical misperceptions. Conclusive evidence that the Trump campaign had colluded with Russia would benefit Democrats, while exoneration would benefit Republicans. Hence, each side had both opportunity and motivation to hold a misperception about the issue. The item tapping these beliefs was embedded in a block of political knowledge questions. Following Prior et al. (2015), the survey encouraged respondents to answer as accurately as possible. The question asked respondents to describe the conclusions of the investigation into Russian hacking as confirming coordination between Russian intelligence and the Trump campaign, confirming that there was no coordination, or lacking conclusive evidence on this question (the correct response). We then constructed two dummy variables: guilty of collusion (12%) and cleared of collusion (21%).

Online Partisan Media

The 2016 survey took a different approach to measuring partisan media use, building on recent methodological advances (Dilliplane, Goldman, & Mutz, 2013). Respondents who indicated that they had gone online for news in the past month were asked to indicate which websites or mobile apps they had used at least once during this period. The list from which they chose included both partisan and non-partisan outlets. A total of 81 sites were displayed in random order across a series of eight screens (including 20 liberal and 20 conservative sites; see Supporting Information Appendix C for the complete list and details about the site selection). Online news use was computed as the number of liberal (M = .90, SD = 1.70) and conservative (M = .79, SD = 1.67) sites a respondent indicated using in Wave 2.

Affective Polarization

We employed the differences between favorability ratings of (a) the two major-party candidates and (b) their supporters in the 2016 U.S. presidential election as key measures of affective polarization. The former has been more widely used, and was what we tested in 2012, but the latter is arguably more consistent with the conceptualization of affective polarization, because it tapped Americans’ attitudes toward other Americans, not toward political candidates (Iyengar et al., 2012). Respondents were asked to indicate their feelings toward each candidate—and, separately, the candidates’ supporters—from 0 (very unfavorable) to 100 (very favorable). A candidate polarization measure was constructed by subtracting each individual’s rating of Clinton from that of Trump, yielding favorability scores ranging from −100 (very favorable to Clinton) to 100 (Wave 2: M = −2.25, SD = 62.96). Supporter polarization was constructed similarly (Wave 2: M = −4.87, SD = 57.53). We averaged these two scores to create the Wave 2 affective polarization measure (Wave 2: M = −3.56, SD = 58.82, alpha = .95).

Control Variables

Control variables included demographics (age, gender, education, income, race), political ideology (range = 1–7, M = 4.09, SD = 1.57), political knowledge (range = 0–3, M = 1.23, SD = .74), political interest (range = 1–4, M = 2.32, SD = 1.01), and following election news (range = 1–4, M = 2.95, SD = .91).

Results

2012 Data

We tested our theoretical model using the 2012 panel in several stages (n = 1563; 521 respondents for each of three waves; see Supporting Information Appendix Table D1 for zero-order correlations). We first discuss the fixed effects model with affective polarization as the outcome, then the fixed effects model with misperceptions about Obama as the outcome, and finally formal mediation analyses building on both models. We then repeat discussion of these analyses with Romney misperceptions.

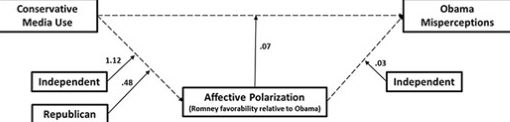

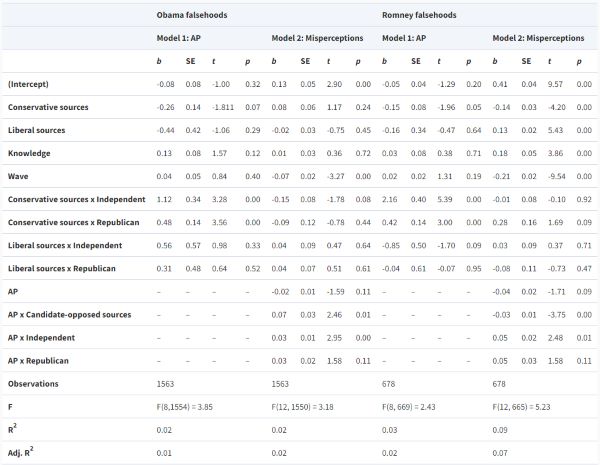

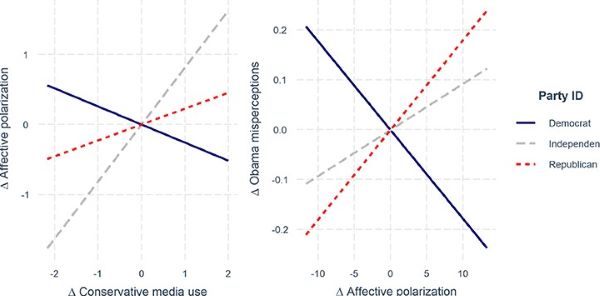

In the first stage, we predicted that increased exposure to conservative media would be associated with increased affective polarization, and that this effect would be strongest among Republican audience members. The results are consistent with these expectations (see Figure 1; Table 1, Obama Model 1). Fixed effects regression offered no evidence that Democrats’ affective polarization changed with conservative media use; however, increases in conservative media use were linked to increases in affective polarization among both Republicans and Independents. Coefficients on the interaction terms with Republicans (B = .48, p < .0001) and Independents (B = 1.12, p < .0001) were significantly larger than zero. Plotting the estimated marginal means between changes in conservative media use and changes in affective polarization helped illustrate these results (see Figure 2, left panel). Regarding the research question, we observed the largest effect among Independents, although the difference in slopes between Republicans and Independents was not precisely estimated (p = .06).

In the second stage of our analysis, we examined the path from affective polarization to Obama misperceptions. Here, we predicted that increases in affective polarization would be associated with increases in misperceptions about Obama, especially among Republicans. Results appeared broadly consistent with these predictions, but were statistically equivocal (Figure 1; Table 1, Obama Model 2). The estimated effect of changes in (pro-Romney) affective polarization was positive for Republicans (simple slope B = .02) and Independents (B = .01), but was negative for Democrats (B = −.02). The effect was significantly more positive for Independents than Democrats (p = .003), and comparing the explained variance of the model with and without the interaction further suggested that the consequences of affective polarization depend on party identity (p = .03). In other words, although the estimated effects of polarization for members of each party were not distinguishable from zero, there were significant differences between parties. Again, a plot of the predicted relationship illustrates the results (Figure 2, right panel). Regarding the research question, we saw no evidence of a difference in the magnitude of affective polarization’s effect among Republicans, compared to Independents.

In the last stage of the Obama misperception analysis, we tested whether affective polarization mediated partisan media’s influence on misperceptions. One cannot use p values of regression terms in the constituent regression models to judge the presence or absence of a mediation effect (e.g., Hayes, 2017); a separate test of mediation is required. Results indicate that there was an estimated overall indirect effect of .009 (95% CI .004–.016; p = .006), providing this article’s strongest evidence for H1. This estimated effect described the change in Obama misperceptions expected for a one-unit change in conservative media use that is mediated by changes in affective polarization. Evaluating this relationship separately for each party affiliation, we observed that the indirect effect was .012 for Republicans (95% CI .003–.021; p = .007). This indirect effect was significantly larger, with a difference of .036 (95% CI .012–.067; p = .006), than the (non-significant) indirect effect among Democrats (−.004, 95% CI −.020 to .006; p = .425). The indirect effect among Independents was also positive, estimated at .040, though variability for the coefficient was considerably higher than for other affiliations (95% CI .006–.075; p = .027). Thus, H2 was supported.

Turning to the research question, we observed that the indirect effect for Independents was greater than the effect for Democrats, with a mean difference of .085 (95% CI .028–.144; p = .003), but that evidence of a difference between Independents and Republicans was negligible, with a mean difference of .052 (95% CI −.004 to .109; p = .068).

Next, we repeated these three analytic stages for Romney misperception, starting with the influence of partisan media use on affective polarization. As claims about Romney had a much lower profile than those about Obama, the sample size was less than half what it was in the prior models (n = 678; 226 respondents in each of three waves). Nevertheless, the pattern of results when predicting affective polarization was the same: conservative media use had a larger effect on Republicans (B = 2.16; p < .001) and Independents (B = .42; p < .001) than Democrats (Table 1, Romney Model 1; Supporting Information Figure S1). Our focus in these models, however, was on liberal source use, which we expected to reduce pro-Romney affective polarization. Our model provided no evidence for an effect of liberal sources on affective polarization (B = −.16, p = .64) and effects did not appear to vary by partisanship, as indicated by testing differences in explained variance of the model with and without the interaction term (p = .25). Testing the path from affective polarization to Romney misperceptions yielded no substantively significant coefficients (Table 1, Romney Model 2; Supporting Information Figure S1). Finally, there was no evidence that the total indirect effect of liberal media use is different than zero (95% CI −.019 to .036; p = .65). Thus, neither hypothesis was supported when modeling the influence of liberal media use on misperceptions about the Republican candidate.5

Replication Using 2016 Data

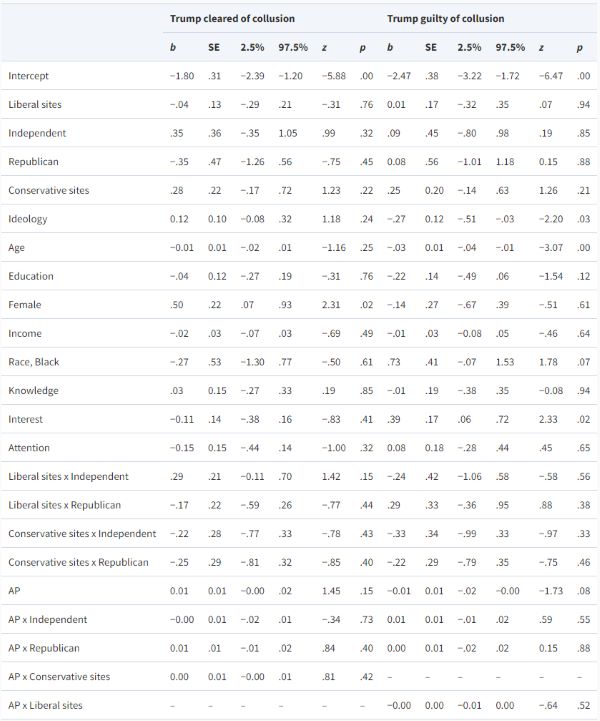

We replicated these results using two waves of data collected during the 2016 election (n = 624; see Supporting Information Table D2 for zero-order correlations). As the target misperception was only measured in the final wave, we could not use fixed effects models. Instead, we used logistic regression-based mediation tests that included several control variables. There were two models: one each for estimating the probability of holding each inaccurate belief. The outcome was measured in Wave 3, and was predicted by Wave 2 media use, as mediated by Wave 2 affective polarization (see Table 2 for coefficients for both models; see Supporting Information Appendix F for model fit statistics).

As with the 2012 results, we found support for our claim that affective polarization mediates the relationship between partisan media use and misperceptions (H1). There was an effect of conservative media use on the belief that Trump had been cleared of collusion—a misperception favored by Republicans—which was mediated by affective polarization (indirect effect = .010, 95% CI .003–.019; p = .007). According to this model, adding one conservative source to an individual’s media diet led to about a 1% greater likelihood of belief in the falsehood. We did not, however, find evidence that the effect varied by party (H2), as the difference between the indirect effects for Republicans and Democrats was non-significant (95% CI −.027 to .018; p = .82). The evidence that liberal media use promoted the belief that Trump was guilty of collusion via affective polarization was unconvincing (indirect effect = .004, 95% CI .001–.009; p = .10), and the difference between the indirect effects for Democrats and for Republicans was non-significant (95% CI −.015 to .013; p = .65).

Discussion

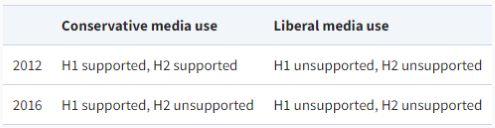

Although not definitive, data collected over the course of two U.S. presidential elections offer evidence that the increase in candidate misperceptions commonly associated with exposure to conservative media use are due, in part, to growing affective polarization. Results are summarized in Table 3. Three-wave panel data collected in 2012 provide evidence consistent with the causal model we proposed, showing that a growing gap in candidate favorability linked conservative media consumption to misperceptions about the Democratic candidate (H1). The data also suggest that this relationship was contingent on the individual’s party affiliation when considering the influence of conservative media (H2). The design and analyses for our 2012 data provide our best evidence for these claims, because key measures were repeated over time and because the analytic methods used were robust to confounding from individual differences. The statistical evidence was strongest in the 2012 data as well. In a Bayesian framework, the p values obtained (.006 for H1, .005 for H2) suggest the data are about 12 times more compatible with the obtained results than a null result, and this figure can be as high as 25 under reasonable assumptions (see Held & Ott, 2018). Data collected in 2016 suggest that the mediated relationship linking conservative media use to misperceptions benefiting Republicans was robust to changes in electoral context and measurement strategy.

There was little evidence of a corresponding effect for liberal media use on misperceptions benefiting Democrats, though we hesitate to make much of this non-finding. We cannot be sure whether these differences were an artifact of the misperceptions studied here, were due to differences in partisan media on the left and the right, or reflect a more fundamental difference in how individuals with different political orientations responded to their information environment (e.g., Jost, 2017; but see Ditto et al., 2019). Whereas falsehoods about Obama were uniformly attractive to members of the opposing party, several of the false claims about Romney were more likely to be damaging among members of his own party. For example, the claim that Romney did not consider himself a Christian was more likely to erode support among evangelical Christian conservatives than among liberals. Furthermore, as previously noted, false statements about Romney had a much lower profile than those about Obama.6 By the end of the 2012 election, 9 in 10 respondents (90%) had encountered the false claim that Barack Obama was a Muslim; in contrast, the most widely heard falsehood about Mitt Romney (that he had signed a law providing taxpayer-funded abortions while serving as governor of Massachusetts: a claim that Republicans were more likely to find objectionable than Democrats) was familiar to just under half (47%) of the sample. As a consequence, tests of misperceptions about Romney relied on considerably smaller numbers of respondents, which meant that the tests had less power for detecting statistically significant differences.

Issue comparability and sample size were less problematic with the 2016 data. Both misperceptions focused on a single issue, and the sample sizes were the same in both analyses, which may be why the results for liberal and conservative media use were more similar, albeit considerably weaker statistically. Still, neither panel was designed to assess why liberal and conservative media use had different effects. This question merits further research. The recent rise of political falsehoods appealing to liberals (Beauchamp, 2017; Levin, 2017) provides a valuable opportunity to study factors that may contribute to their circulation and acceptance.

The results concerning the consequences of conservative media use are likely unsurprising to many readers: that partisan media exposure promotes affective polarization is well documented (e.g., Lelkes et al., 2017; Levendusky, 2013), and there are numerous reasons to expect that increasingly negative feelings toward a political outgroup would encourage individuals to believe politically expedient falsehoods. Although the effect sizes were small, as is often the case when studying media, the relationships were consistently mediated by affective polarization. Further, we only considered a handful of falsehoods; if these patterns apply to the full range of inaccurate claims in circulation today, the cumulative effects could be substantial. To the extent that media shape belief expressions, these data are consistent with the assertion that promoting political animosity is a key part of how they do so. The implications are striking: partisan media do not have to advance falsehoods explicitly in order to promote their endorsement. Encouraging hostility toward political opponents has the same effect, while allowing outlets to avoid the reputational harms that come from sharing inaccurate information. Documenting this dynamic in a real-world setting highlights its importance, suggests opportunities for keeping misperceptions in check, and sets the stage for future research.

This study has important limitations. First, since these analyses were based on self-reported data, it is likely that respondents overstated their news consumption (Prior, 2009). More troublingly, it is possible that the strength of social identity could have biased measures of exposure, affective polarization, and, potentially, even belief. This is a serious threat to the interpretation of the results offered here. However, we believe that the measures used provide a reasonable test of our theoretical predictions. The site-listing approach used in 2016 has been shown to have acceptable validity and reliability (Dilliplane et al., 2013), and though imperfect, it represents the current standard in survey research. Furthermore, we note that the 2012 and 2016 data sets yielded consistent results, despite relying on different measurement approaches. In our view, consistency across varied measurement approaches, different contexts, and distinct samples strengthens our argument.

Second, since the 2016 candidate belief was only measured in the third wave, we had to rely on analyses using only two waves of data when examining these factors. The consistency between the cross-sectional and longitudinal analyses increases confidence in the robustness of our results, but this is a relatively weak replication. An experimental design and studies using large-scale observational data are obvious next steps. Finally, we note that future work should examine more systematically the measurement issues related to assessing affective polarization. The measures used here were modeled on foundational work in this area (Iyengar et al., 2012), but they have limitations. Candidate favorability is an imperfect proxy for hostility toward members of an opposed party, and though favorability toward candidate supporters has better face validity, there has been no work validating it. Additional scholarship addressing the conceptualization and measurement of affective polarization would be valuable (e.g., see Druckman & Levendusky, 2019).

A third concern stems from a growing debate in the field over when mediation analysis can be meaningfully employed to identify causal mechanisms. Imai and colleagues demonstrated that mediation testing is premised on an assumption of sequential ignorability (Imai, Keele, Tingley, & Yamamoto, 2011). That is, for a mediation analysis to provide robust evidence of a process, there can be no omitted variable bias for either the path from primary predictor to mediator nor the path from the mediator to the outcome. Conventional randomized experiments can rule out confounding for the effect of the predictor on the mediator, but they do not rule out confounding of the mediator-outcome relationship. Even running separate experiments for each relationship cannot completely satisfy the assumption. The fixed effects approach employed here helps, by virtue of controlling for all stable characteristics, but it is at least possible that changes in other time-varying factors besides partisan media use could have influenced both affective polarization and falsehood endorsement. Like any assumption, plausibility should be assessed here based on prior research results and the theoretical argument underlying the hypothesized process.

Given these limitations, it would be a mistake to treat this issue as settled. The patterns observed here are consistent with what we believe is a compelling theoretical argument, but other explanations of these results are conceivable. At the same time, though, we believe that these results provide a useful, if tentative, step forward. In helping to explain how conservative media exposure promotes misperceptions, this work underscores the harmful consequences of affective polarization. Not only does the growing hostility felt by partisans on both sides of the aisle toward their political opponents make compromise less likely, it also appears to make partisans more likely to accept falsehoods critical of the political outgroup. This poses a significant challenge to American democracy. Americans’ hostility toward their political opponents is at an all-time high (Iyengar et al., 2012), and there is some evidence that, thanks to partisan cable and online news, it is growing faster than ever (Hmielowski et al., 2015; Lelkes et al., 2017). If this hostility translates into a willingness to believe anything that members of your party tell you, regardless of empirical evidence or claims made by those not belonging to the ingroup, then the U.S. political situation is dire. Navigating political differences requires an ability to arrive, with political opponents, at a common set of empirical truths around which solutions, including compromises, can be built.

If there is a positive take on these results, it is that it may be possible to offset partisan media’s harmful influence if we can find other ways of reducing the affective polarization that accompanies exposure to such outlets. Perhaps the technological capabilities that have facilitated the emergence of polarization-inducing partisan media can also be channeled in ways that promote tolerance, if not fondness, for those who hold views that differ from our own.

See footnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by the Journal of Communication 69:5 (10.14.2019, 490-512) to the public domain.