Toxic polarization is deepening in the United States.

By Dr. Alex Hinton

Distinguished Professor of Anthropology

Director, Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights

Chair on Genocide Prevention, UNESCO

Rutgers University

Introduction

“So, what is one thing that you want Wisconsinites to know or do around the upcoming election?” the moderator asks.

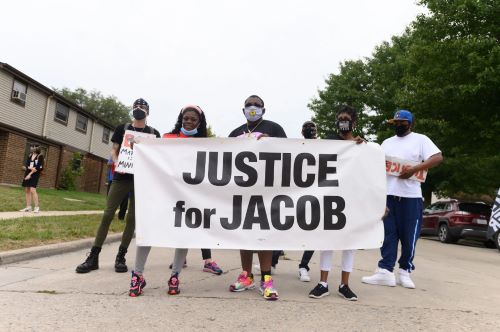

I’m in a conference room in a Civil War museum in Kenosha, Wisconsin, attending a keynote panel about preventing violence in the lead-up to the U.S. election in November. In 2020, Kenosha became a hotspot for civil unrest when a white police officer shot and paralyzed Jacob Blake, a Black man. During the protests that erupted in the days that followed, Kyle Rittenhouse, a white 17-year-old, shot three people, killing two.

Four years later, the city’s residents are still reckoning with this violence and the underlying divisions that led to it. Beyond Kenosha, nearly half the U.S. believes the country is on the brink of disaster, with democracy under attack and civil war likely. Politicians and pundits stoke the partisan flames, dividing the U.S. into deeper hues of red and blue. With the 2024 election looming, and the memory of the January 6, 2021, capitol insurrection still fresh, many warn the situation could get worse.

But if there are lessons to be learned about how to decrease the polarization in America and promote civil dialogue, it is in spaces like this panel. The moderator is Lisa Inks, a senior director at Urban Rural Action (UR Action for short), a grassroots organization working to prevent targeted violence in communities like Kenosha. UR Action’s mission is building bridges across political, ideological, religious, generational, racial, and geographic divides.

This panel is part of a UR Action public event on July 28, 2024, called “Wisconsinites Uniting for a Safe Election Season.” It is attended by UR Action program participants—called “Uniters”—other members of the community, and local media. One speaker discusses the danger of social isolation, loneliness, and being stuck in informational and social media “bubbles.” The next describes the heightened threats against election officials and queer and immigrant communities. An activist encourages the audience to build networks and “get out of those silos.” A lawyer notes the legal channels that protect election officials and voters.

Throughout the panel, I notice Inks’ colleague Joe Bubman nodding along as he leans against the back wall. Bubman is the founder and executive director of UR Action. Bubman and Inks met while working for Mercy Corps, a humanitarian aid agency that operates in conflict sites around the globe. In 2016, they had a hallway conversation about how toxic polarization in the U.S. resembled the fragile situations in the places Mercy Corps operated. They wondered if the depolarization methods they were using could be applied in the U.S.

Bubman decided to find out. He established UR Action, joining other international conflict resolution actors who followed this path. In contrast to larger cross-partisan organizations like Braver Angels, Bubman decided to focus on smaller, more diverse cohorts—like the Uniters—who would work together on joint community action projects for longer periods of time.

As Inks put it, “We go deep, and they go wide.”

As an anthropologist of violence and peace, I’ve found myself on a similar path of turning my focus to the U.S. For years, I researched and wrote about conflict around the world. But in 2016, I became increasingly concerned with the intensifying political unrest I witnessed at home—a topic I explored in a recent book, It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US.

Now I’m examining how to prevent political violence—and how methods of peacebuilding used around the world could help pave the way.

By the end of the day I spent with UR Action’s staff and participants, I had three key takeaways. The first came from a children’s game.

Beware of Us-Them Thinking

“Lock eyes with someone,” Michael Holden instructs the audience of 50. “We’re going to play Rock, Paper, Scissors—Kenosha style.”

The audience laughs.

“That means we end with ‘go,’” he adds. “If you say ‘shoot,’ you’re disqualified since we’re here to prevent violence.”

Holden, an educator, serves as the Kenosha-Racine County coordinator of UR Action’s Uniting to Prevent Targeted Violence in Southeast Wisconsin program, which everyone calls “UPTV.” The Department of Homeland Security–funded program includes 28 Uniters from cities, suburbs, and farms across five counties in southeast Wisconsin, most pink and red (Kenosha, Racine, Walworth, and Waukesha) and one deep urban blue (Milwaukee).

The Uniters, who hold views across the political spectrum, have committed themselves to helping prevent future acts of targeted violence. They do so by learning to “dialogue across difference” and by working together on community projects that address root causes. They will present these projects later today.

But now it’s time to play.

“Go find a partner,” Holden tells us. “After you win, the person you defeat will become your biggest cheerleader. We want you loud!”

Chants of “Rock, Paper, Scissors, go!” begin.

I lose in the second round and stand behind my victor. She loses the next round. We both stand behind the person who defeated her. Larger and larger groups form until there are two winners standing.

They face off for a best-of-three, each backed by a cheering entourage.

“One of the things we just saw,” Holden says to the group afterward, turning serious, “is how this turned into us versus them.”

I think to myself how quickly—and with little thought—we’d done so by following instructions from an authority figure.

A first lesson learned: Remain vigilant against us-them thinking—and the pundits and leaders who fan the flames of division.

Remember the ABCs of Constructive Dialogue

“Read this sentence and tell me how many ‘Fs’ you see,” says Bubman in a breakout session that follows next. A slide reads,

THOSE OF US WHO FOCUS ON ISSUES OF FAIRNESS TOO OFTEN AFFECT AGREEMENT BY GIVING IN INSTEAD OF FIRST USING OUR POWERS OF PERSUASION TO AFFECT A FAIR OUTCOME THAT FULLY SATISFIES ALL OF OUR LEGITIMATE INTERESTS.

I race through, get five. Not confident, I count again—seven. Reading again, the number jumps to 10.

Bubman canvases the room. I finish last. The answer is 16.

A quick lesson learned: Watch your assumptions. Two people can “read” the same situation—even a single sentence—in starkly different ways.

Bubman hands each of us a laminated plastic card titled, “The ABCs of Constructive Dialogue.” The three letters occupy the points of a triangle.

The A at the top refers to asking. An explanatory box explains, “ASK to understand their perspective.” B means to “BREAK down our view so they understand our reasoning.” C stands for “CHECK our understanding of their perspective.”

The ABCs—influenced by research-based mediation techniques developed by the Harvard Negotiation Project—require active listening. “LISTEN—Attentively to words, tone, and body language + with an open and curious mind,” reads the card.

“What I’d like you to do now,” Bubman instructs, “is to write down a question you’d like to ask someone else in this room that relates to political division.” Each member of our group of three takes on the role of either speaker, active listener, or coach, who gives feedback.

I’m assigned active listener. “What are the primary drivers of political division?” I ask. “And which ones are now amplified?”

The speaker pauses, then replies, “Being stuck in different information silos. Like NPR and Fox News.”

“How are they different?” I follow up.

Afterward, the coach says I should have “checked” the speaker’s perspective more by summarizing what she was saying and asking if my understanding was correct.

An ABCs lesson learned: Constructive dialogue is hard. To do it effectively, you have to listen deeply, unpack the other person’s perspective through open-ended questions and checking, and push aside the desire to prove you are right.

Shake a Hand and Break Bread

UR Action’s emphasis on trust building across divides is based on “contact theory,” which holds that intergroup conflict diminishes when members participate in social interactions, especially in situations where they cooperate and share common goals. Contact theory informs much work within global conflict prevention organizations, including that of Mercy Corps, where Bubman and Inks learned and observed the efficacy of peacebuilding techniques they now use at UR Action.

Along these lines, UR Action brings diverse groups like the Uniters into sustained contact. As participants collaborate, they build relationships, mutual respect, and trust.

They do so, in part, by mixing hard work with fun, including through games like Rock, Paper, Scissors. Earlier in the summer, UR Action had held a kick-off meeting in Kenosha that brought Uniters together for bingo and chocolate truffle tasting.

During the event I attended, each Uniter county group in the UTPV-Wisconsin program presented on a project they’re designing in collaboration with a local partner. They explained how their projects would improve mental health services and address a lack of social cohesion in their communities, which they see as root causes of targeted violence.

This work provides a final lesson learned: Depolarization is enhanced by trust building and contact—which help people get out of their bubbles, dialogue across difference, and break down the reductive us-them distinctions that undergird division.

Given that the U.S. confronts toxic polarization and the threat of violence—not just in the 2024 election cycle but far beyond—such lessons are urgent. UR-Action’s Uniters demonstrate that, even at such perilous moments, it remains possible to lower the political temperature and to dialogue across the red-blue divide.

Originally published by SAPIENS, 10.17.2024, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.