Clues found in 1.77-million-year-old teeth.

By Alexa Robles Gil

Science Journalist

Unlike other mammals, humans experience an extended childhood. Human children continue to grow and be reliant on their parents for a much longer time, compared to other species. Although different theories surround the reason for this long-lasting life stage, one of the more popular ones suggests it’s due to the development of bigger brains. Now, clues to the origins of our long childhood have been found in 1.77-million-year-old teeth.

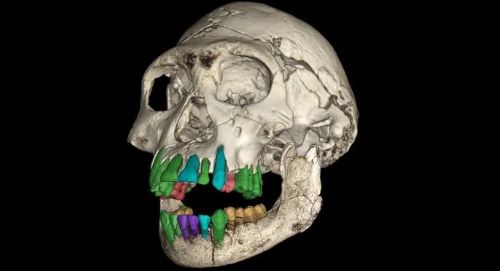

In a new study published in Nature, researchers analyzed the growth of the teeth of a prehistoric youth who lived in what is now Dmanisi, Georgia. They found that the fossil teeth of the 11-year-old individual, belonging to our genus, Homo, experienced delayed development like those of modern human children during the first several years of life. Then, they took on more great ape-like growth.

If we compared the length of human childhood to that of other primates, “a great ape would probably barely have time to go to kindergarten, and then it’s already an adult,” says lead author Christoph Zollikofer, a paleoanthropologist at the University of Zurich, to Popular Science’s Laura Baisas. Humans, on the other hand, spend a massive amount of time “growing up in a very complex social environment.”

A key question in paleoanthropology is determining when this pattern of slow development first emerged in our genus, Alessia Nava, a bioarchaeologist at the Sapienza University of Rome who was not part of the study, says to Science’s Ann Gibbons.

“Now, we have an important hint,” she adds.

To dig into this mystery, the researchers measured growth lines in the prehistoric youth’s molars. These growth lines in teeth are similar to a tree’s rings. Like a tree adds a layer of material to its trunk each year, teeth accumulate layers of dentin that offer a glimpse into the development of the individual.

“You can cut the tooth and see the growth rings and see how it grew. It can be like a movie of how the tooth developed from birth to death,” Zollikofer tells Popular Science.

Past research had focused on fossil teeth of individuals up to 4 years old, says paleoanthropologist Kevin Kuykendall at the University of Sheffield in England who was not involved in the study, to Science News’ Bruce Bower. This is the first “fairly complete” reconstruction of the dental development in an ancient hominid, he tells the outlet.

The newly examined teeth were found in 2001, and they were well-preserved enough that the team was able to take X-ray images of their growth lines. Through this imaging, the researchers studied how the different teeth formed and developed over the youth’s lifetime.

They compared the teeth’s growth to those of modern humans and other great apes, such as chimpanzees. The findings fell somewhere in between: The youth’s dentition followed a slow, human-like growth until about 4 years of age, per the paper, then caught up to chimpanzee-like growth around age 8. The youth would have reached dental maturity at around 12 to 13.5 years old.

For Debbie Guatelli-Steinberg, a paleoanthropologist at Ohio State University, “the big takeaway is that we start seeing this slowdown before a major increase in brain size,” she tells Science. The “very exciting” findings suggest Homo species may have developed long childhoods to spend more time learning social behavior, before brain development intensified.

Still, Kuykendall points out to Science News that it’s hard to draw definitive conclusions. Rather than being linked to social learning or brain size, slow dental development in early Homo individuals might have been shaped by which foods were available or the age at weaning.

Although the new study offers hints into the evolution of the extended period of growth in humans, “many puzzles remain,” writes Guatelli-Steinberg in Nature’s News and Views. Studying chemical signatures in fossil tooth enamel, for example, could shed more light on the origins of humans’ prolonged childhood.

Originally published by Smithsonian Magazine, 11.15.2024, reprinted with permission under a Creative Commons license for educational, non-commercial purposes.