Majorities predict a weaker economy, a growing income divide, a degraded environment, and a broken political system.

By Kim Parker, Rich Morin, and Juliana Menasce Horowitz

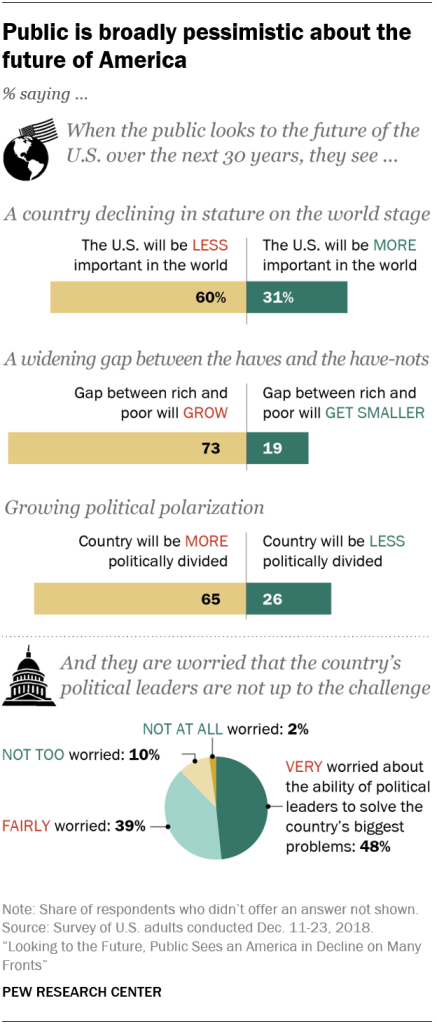

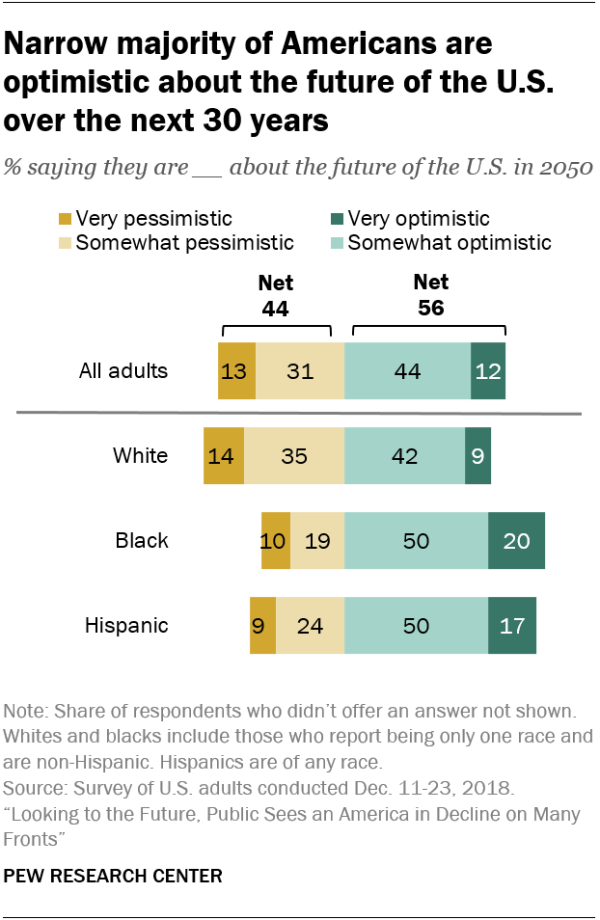

When Americans peer 30 years into the future, they see a country in decline economically, politically and on the world stage. While a narrow majority of the public (56%) say they are at least somewhat optimistic about America’s future, hope gives way to doubt when the focus turns to specific issues.

A new Pew Research Center survey focused on what Americans think the United States will be like in 2050 finds that majorities of Americans foresee a country with a burgeoning national debt, a wider gap between the rich and the poor and a workforce threatened by automation.

Majorities predict that the economy will be weaker, health care will be less affordable, the condition of the environment will be worse and older Americans will have a harder time making ends meet than they do now. Also predicted: a terrorist attack as bad as or worse than 9/11 sometime over the next 30 years.

These grim predictions mirror, in part, the public’s sour mood about the current state of the country. The share of Americans who are dissatisfied with the way things are going in the country – seven-in-ten in January of 2019 – is higher now than at any time in the past year.

The view of the U.S. in 2050 that the public sees in its crystal ball includes major changes in the country’s political leadership. Nearly nine-in-ten predict that a woman will be elected president, and roughly two-thirds (65%) say the same about a Hispanic person. And, on a decidedly optimistic note, more than half expect a cure for Alzheimer’s disease by 2050.

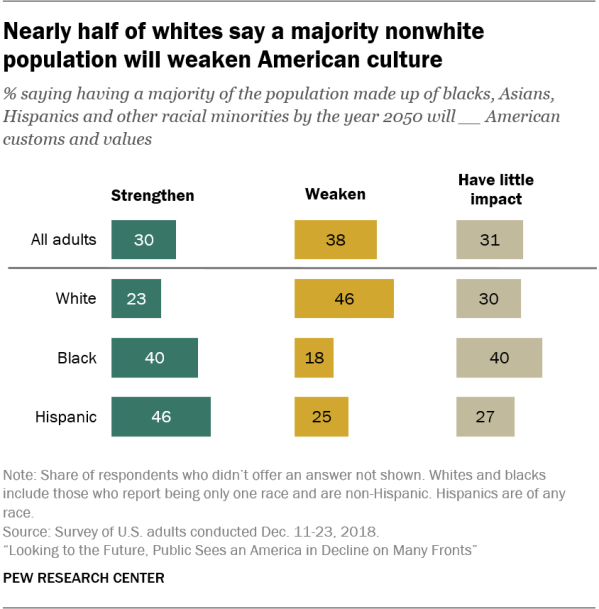

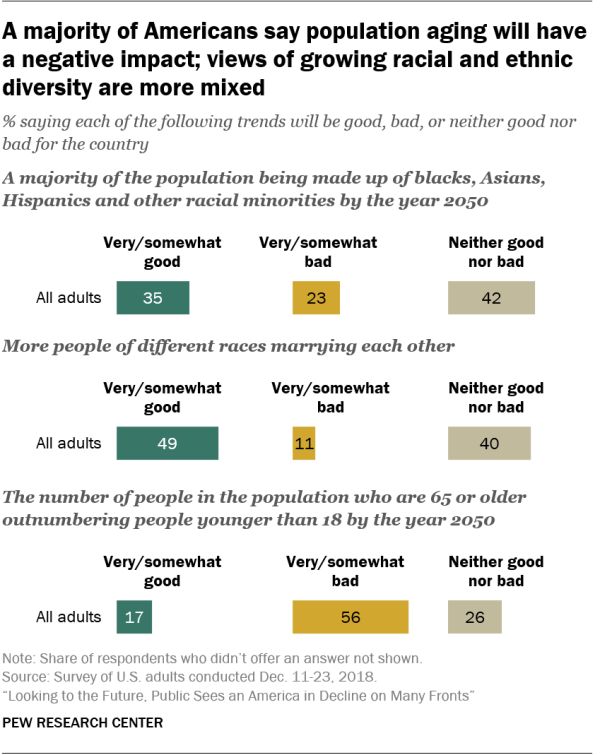

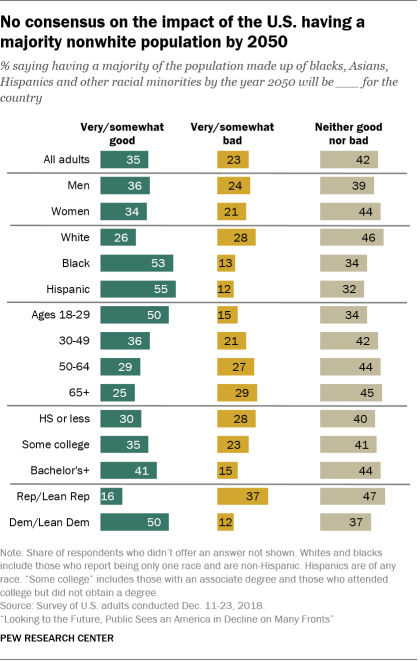

The public also has a somewhat more positive view – or at least a more benign one – of some current demographic trends that will shape the country’s future. The U.S. Census Bureau predicts that, by 2050, blacks, Hispanics, Asians and other minorities will constitute a majority of the population. About four-in-ten Americans (42%) say this shift will be neither good nor bad for the country while 35% believe a majority-minority population will be a good thing, and 23% say it will be bad.

These views differ significantly by race and ethnicity. Whites are about twice as likely as blacks or Hispanics to view this change negatively (28% of whites vs. 13% of blacks and 12% of Hispanics). And, when asked about the consequences of an increasingly diverse America, nearly half of whites (46%) but only a quarter of Hispanics and 18% of blacks say a majority-minority country would weaken American customs and values.

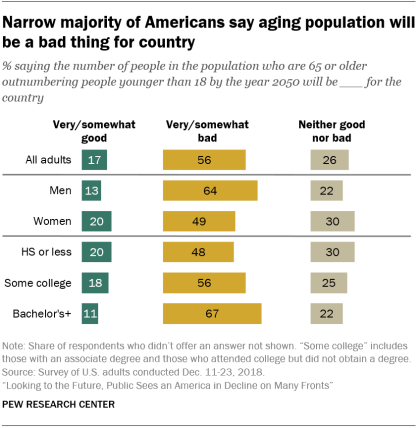

The public views another projected change in the demographic contours of America more ominously. By 2050, people ages 65 and older are predicted to outnumber those younger than 18, a change that a 56% majority of all adults say will be bad for the country.

In the face of these problems and threats, the majority of Americans have little confidence that the federal government and their elected officials are up to meeting the major challenges that lie ahead. More than eight-in-ten say they are worried about the way the government in Washington works, including 49% who are very worried. A similar share worries about the ability of political leaders to solve the nation’s biggest problems, with 48% saying they are very worried about this. And, when asked what impact the federal government will have on finding solutions to the country’s future problems, more say Washington will have a negative impact than a positive one (55% vs. 44%).

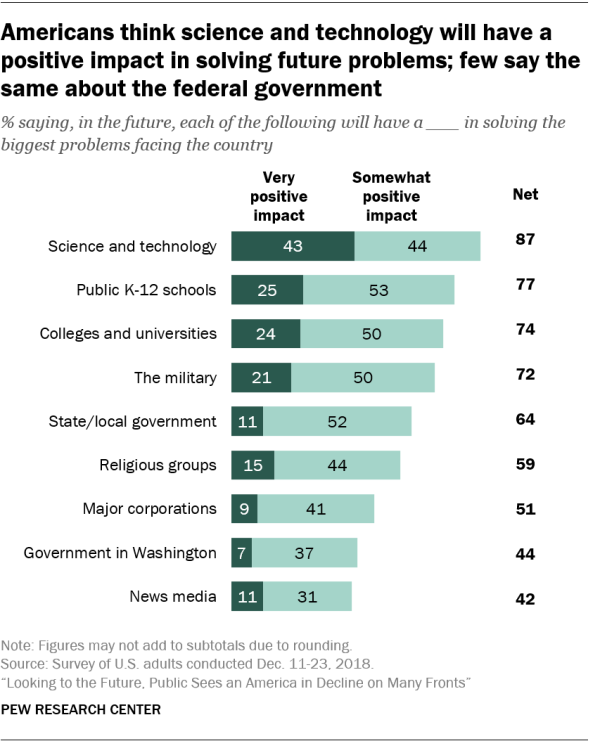

Instead, large majorities of Americans look to science and technology as well as to the education system to solve future problems: 87% say science and technology will have a very or somewhat positive impact in solving the nation’s problems, and roughly three-quarters say the same about public K-12 schools (77%) and colleges and universities (74%). Even so, roughly three-quarters (77%) worry about the ability of public schools to provide a quality education to tomorrow’s students, and more expect the quality of these schools to get worse, not better, by 2050. And only about a third (34%) of the country rates increased spending on scientific research as a top policy priority.

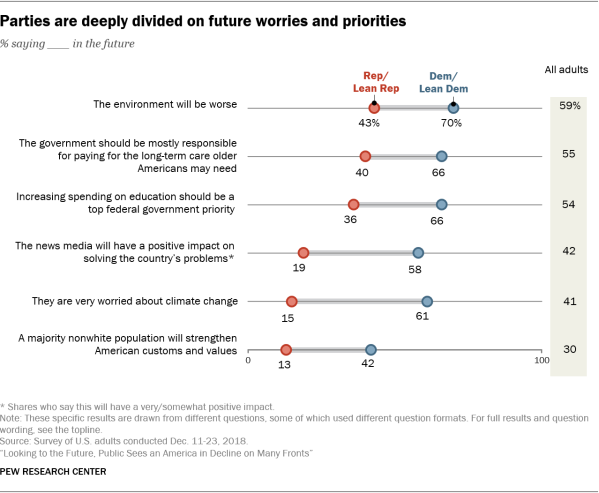

Underlying many of these and other findings are deep divisions along the traditional fault lines of American life, including race, age and education. However, among the more striking differences found in this survey are those between Republicans and Democrats. Taken together, the size and frequency of these differences underscore the extent to which partisan polarization underpins not just the current political climate but views of the future as well.

Across a range of issues, the difference between partisans is not merely apparent, but conspicuously large. Despite shared concern about the future quality of the nation’s public schools, about two-thirds of Democrats and those who lean Democratic (66%), but only 36% of Republicans and Republican leaners, rate increased spending on education as a top federal government priority. About six-in-ten Democrats (58%) but only 19% of Republicans say the news media will have a positive impact on solving the country’s future problems. About four-in-ten Democrats (42%) say a majority-nonwhite population will strengthen American customs and values, a view expressed by only 13% of Republicans. Similarly, about six-in-ten Democrats (61%) but just a third of Republicans consider the growth of interracial marriage to be a good thing for society. Partisan gaps on future priorities reflect similar gaps in current policy priorities. Recent research has shown that Republicans and Democrats have moved farther apart in recent decades in their views on what the top priorities for Congress and the president should be.

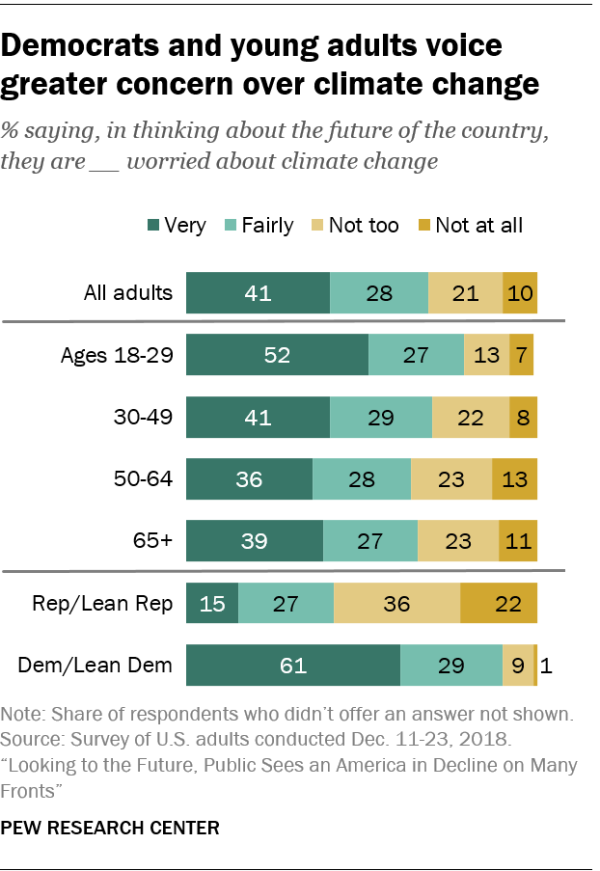

Partisan differences are particularly large on issues related to the environment. About six-in-ten Democrats (61%) but only 15% of Republicans say they are very worried about climate change. An even larger share of Democrats (70%) predict the condition of the environment will get worse in the next 30 years, while 43% of Republicans agree.

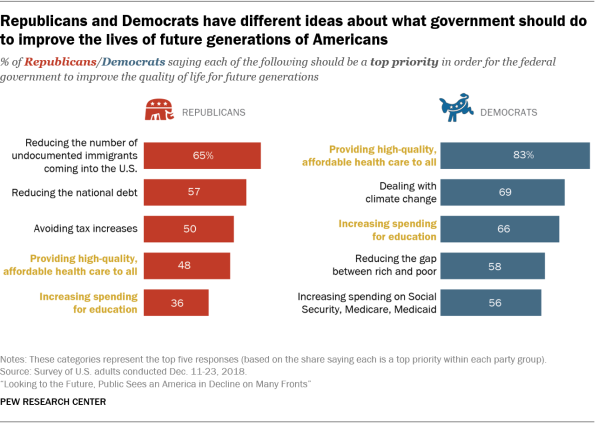

Even their top priorities for the future are, in many instances, strikingly different. Among all adults, health care and increased spending on education topped the list of policies that the public believes the federal government should enact to improve the quality of life for future generations. Yet the top-three Republican priorities – reducing the number of undocumented immigrants, cutting the national debt and avoiding tax increases – don’t even appear among the Democrats’ highest five priorities.

Conversely, three of the five Democratic priorities – dealing with climate change, reducing the gap between rich and poor, and increasing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid – are absent from the GOP’s top-five list. Providing high-quality health care and increasing spending on education are top priorities for each party, though larger shares of Democrats than Republicans rank these issues as top priorities.

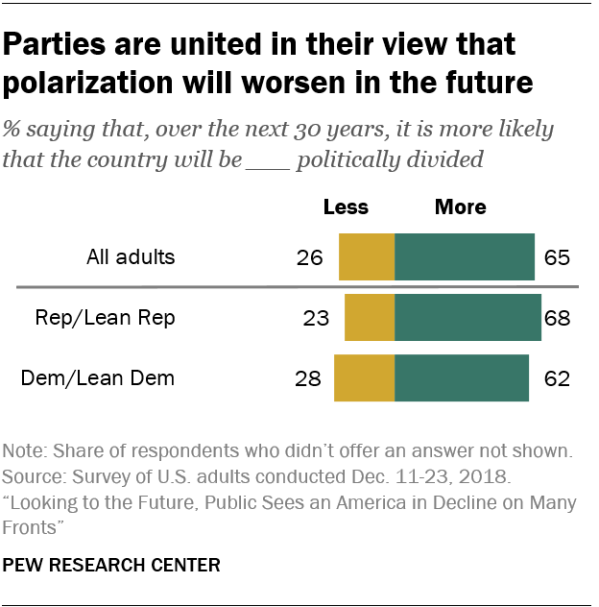

It is perhaps fitting that, while the two parties hold similar views on a number of issues, one area of agreement stands out: Majorities of both parties agree that the country will be more politically divided in 2050 than it is today.

The nationally representative survey of 2,524 adults was conducted online Dec. 11-23, 2018, using Pew Research Center’s American Trends Panel.1 Among the other key findings:

Majorities of Americans predict a tougher time financially for older adults in 2050

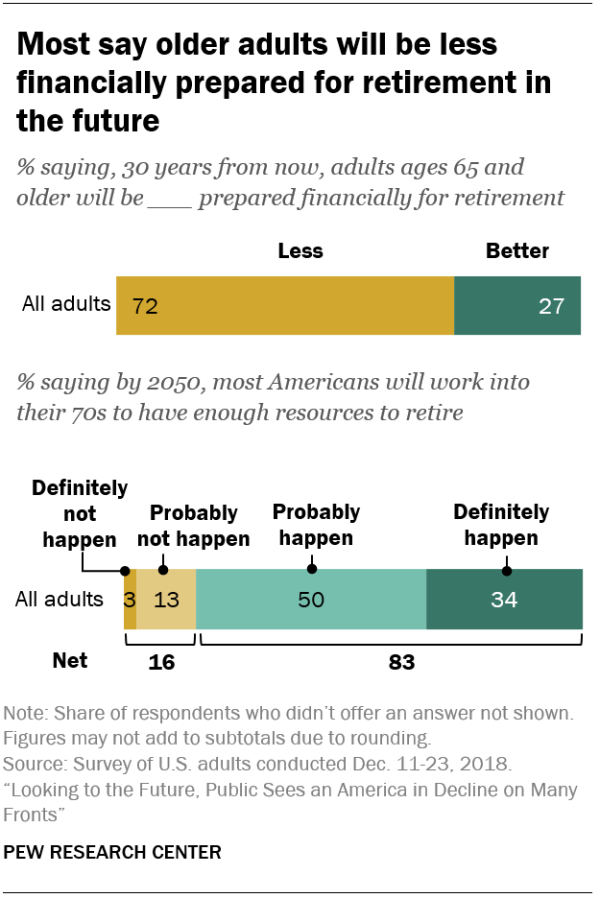

About seven-in-ten Americans (72%) expect older adults will be less prepared financially for retirement in 2050 than they are today. An even larger share (83%) predict that most people will have to work into their 70s in order to afford to retire. And the public’s forecast for the future of the Social Security system is decidedly grim.

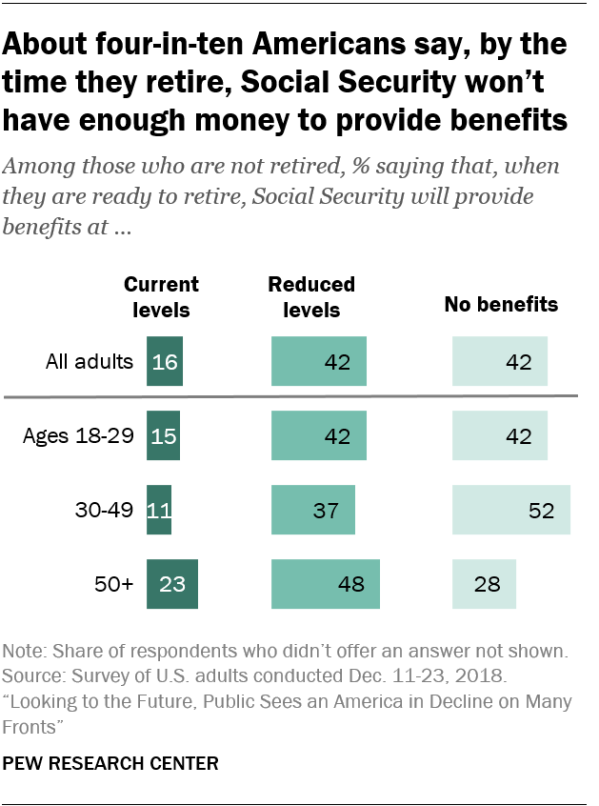

Among those who are not yet retired, 42% expect to receive no Social Security benefits when they leave the workforce, and another 42% anticipate that benefits will be reduced from what they are today.

Adults younger than 50 are particularly doubtful that Social Security will be there when they leave the workforce: 48% expect to receive no Social Security benefits when they retire. By contrast, 28% of those who are 50 or older are similarly pessimistic. But even among this older group, only about a quarter (23%) expect to receive Social Security benefits at current levels. These findings reflect a long-standing skepticism – particularly among young adults – about the long-term solvency of the Social Security system.

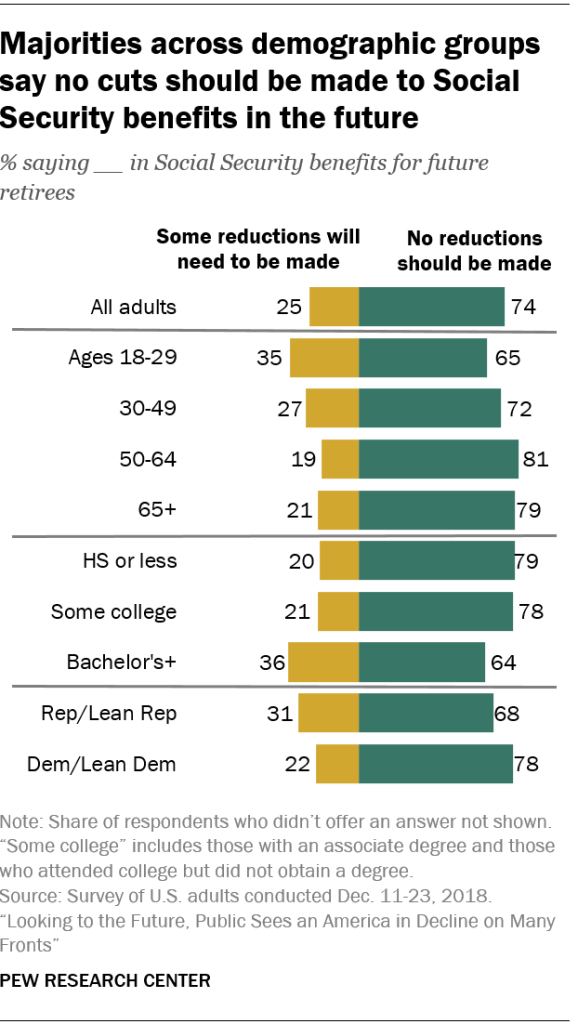

Even as they doubt the long-term financial viability of the Social Security system, most Americans reject reducing benefits. Only a quarter believe that some reductions in benefits for future retirees will need to be made to shore up the system’s finances, while about three times as many say benefits should not be reduced in any way.

Few Americans predict a better standard of living for families in 2050

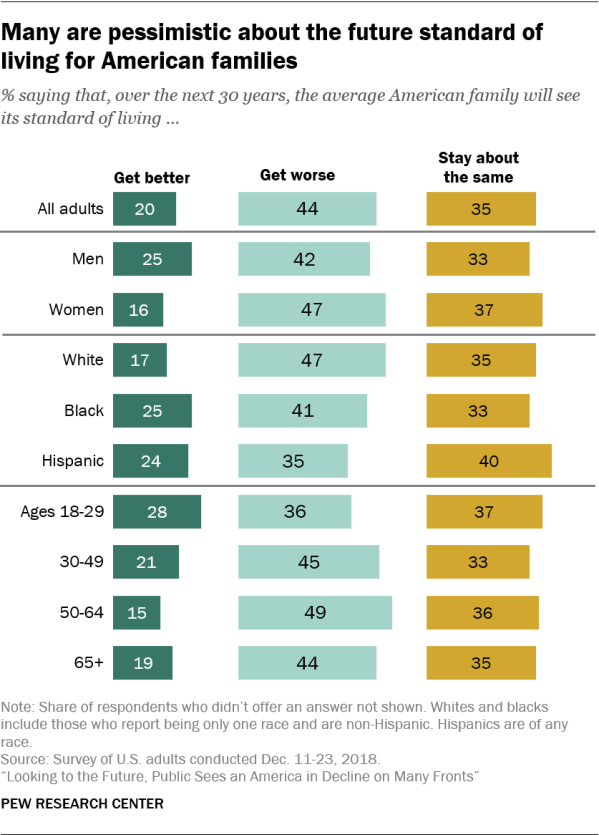

More than four-in-ten Americans (44%) predict that the average family’s standard of living will get worse rather than better over the next 30 years. That’s roughly double the share (20%) who expect families to fare better financially in the future than they do today; 35% predict no real change.

When it comes to prospects for children, half of the public says children will have a worse standard of living in 30 years than they do today, while 42% predict that they will be better off. Men are more likely than women to say children’s standard of living will be higher in 30 years than it is today (47% vs. 36%), while those who do not have children in the home are somewhat more pessimistic about this than those who do (52% vs. 44% say children will have a worse standard of living).

Large majority says health care for all would benefit future generations

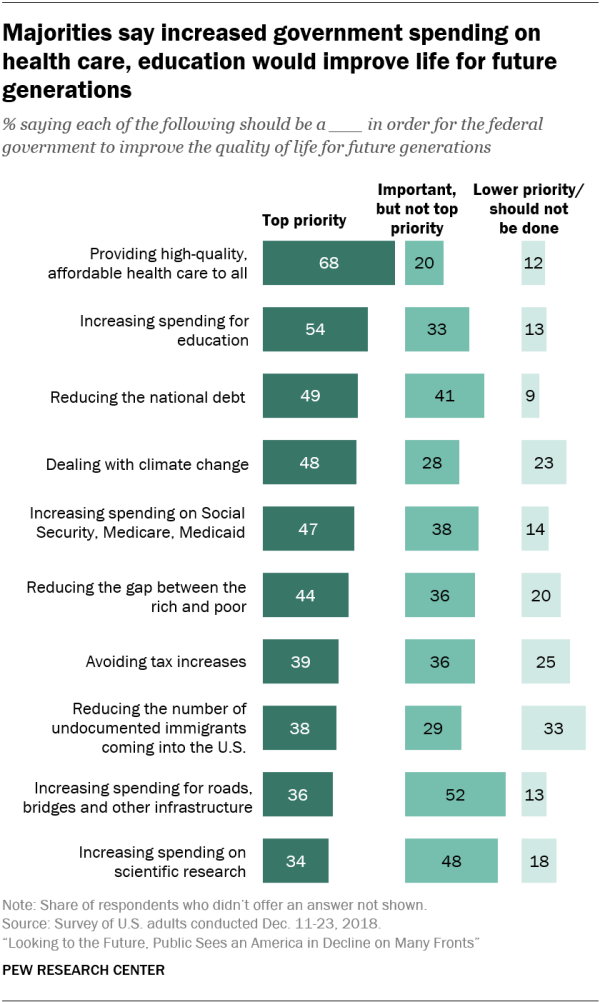

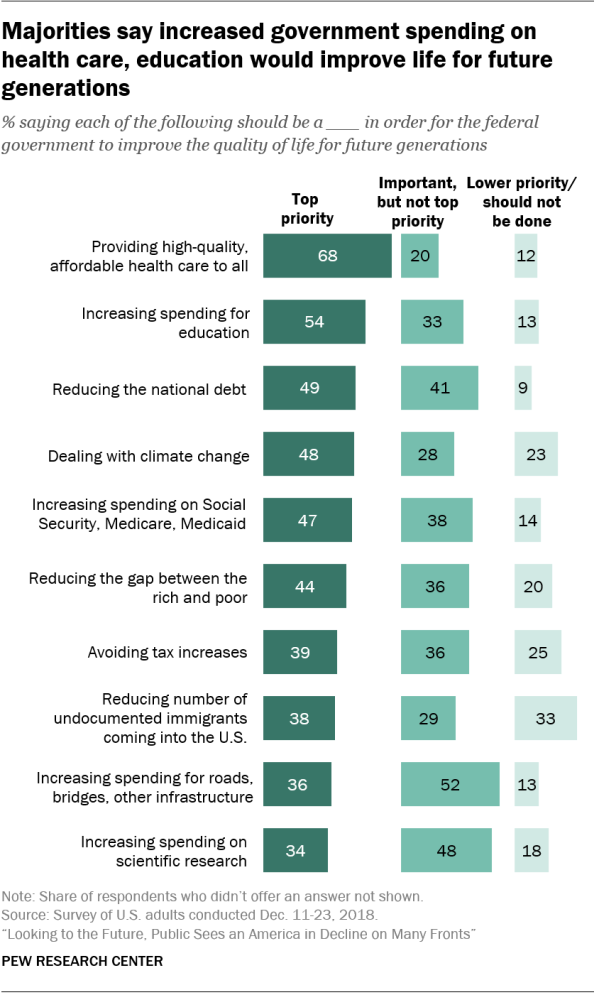

When asked what the federal government should do to improve the quality of life for future generations, providing high-quality, affordable health care to all Americans stands out as the most popular policy prescription. Roughly two-thirds (68%) say this should be a top priority for government in the future.

Increased spending on education is somewhat less popular; 54% say more money for schools should be a top federal government priority in order to improve life for future generations. Slightly fewer say the same about reducing the national debt or dealing with climate change (49% and 48%, respectively, say each should be a top priority). A larger share of Republicans than Democrats prioritize cutting the debt, while just the opposite is true for climate change.

Increasing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid is viewed as a top priority by 47% of adults, and reducing the gap between rich and poor is seen as such by 44%. Falling further down the list are avoiding tax increases, reducing the number of undocumented immigrants coming into the U.S., increasing spending on infrastructure and more money for scientific research.

Minorities are more optimistic than whites about the country’s future

Overall, 56% of all adults say they are either very optimistic (12%) or somewhat optimistic (44%) about the U.S. in 2050. But more than four-in-ten (44%) see the country’s future more darkly, including 13% who say they are very pessimistic and 31% who are somewhat pessimistic about America in 30 years.

Black and Hispanic adults are among the most optimistic about the country’s future. Seven-in-ten blacks and two-thirds of Hispanics feel hopeful about America’s future. In contrast, about half of all whites (51%) are as confident. High school graduates and those with less education also are somewhat more positive about the country’s prospects than are college graduates (60% vs. 53%).

Unlike the wide partisan differences seen elsewhere in this survey, Democrats and Republicans are about equally optimistic when it comes to these broad predictions about America’s future.

The racial pattern switches when Americans are asked about the future of race relations over the next 30 years. Slightly more than half of all whites (54%) but 43% of blacks and 45% of Hispanics say relations will get better. Overall, the country is divided on the future of race relations: About half (51%) say they will improve, while 40% predict they will get worse.

Most Americans worry about the country’s moral values; half say religion will become less important

Roughly four-in-ten Americans (43%) say they are very worried about the nation’s morals, while another 34% are fairly worried. For Republicans, the country’s moral health is a major concern: Roughly half (49%) say, when they think about the country’s future, they are very worried about the moral values of Americans. Only about a third of Democrats (36%) are equally worried. Women are more concerned about the country’s morals than men (46% vs. 38%), while older Americans are more worried than those younger than 50 (49% vs. 37%).

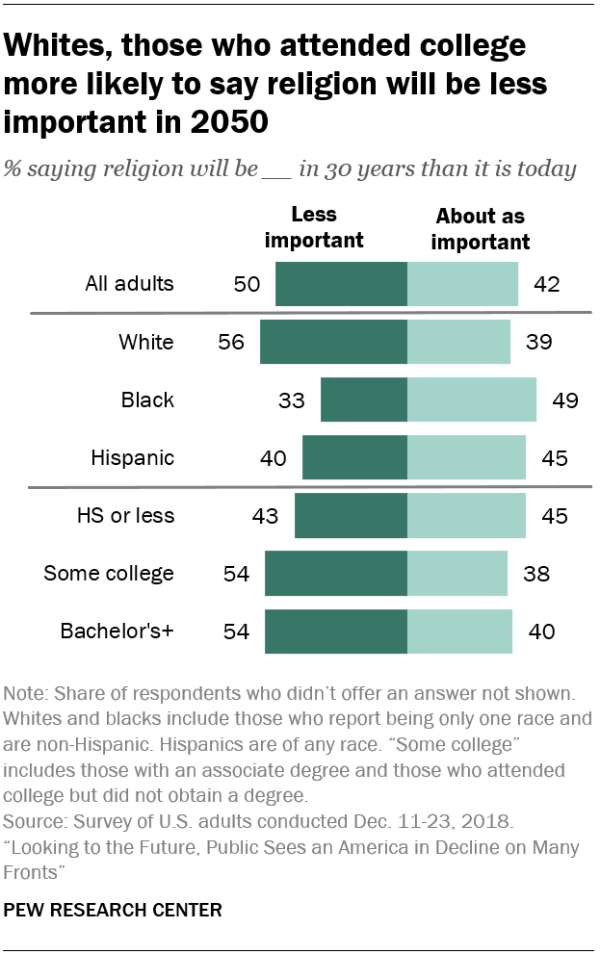

The public is divided over whether religion will become less important over the next 30 years than it is now. Half say religion will lose importance, while 42% say it will remain unchanged (respondents were not given the option of saying religion will be more important).

A majority of whites (56%) but only a third of blacks and four-in-ten Hispanics say the importance of religion will decline over the next 30 years. Adults with more formal education are more likely to see religion in eclipse than those with less: 54% of all college graduates but 43% of those with a high school degree or less education predict the declining importance of religion.

Among religious groups, roughly equal shares of white evangelicals (52%), white mainline Protestants (51%) and white Catholics (54%) say religion will be less important in the future – a view held by a similar share (59%) of those who are atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular.

Older adults, those with less education more negative about the impact of automation

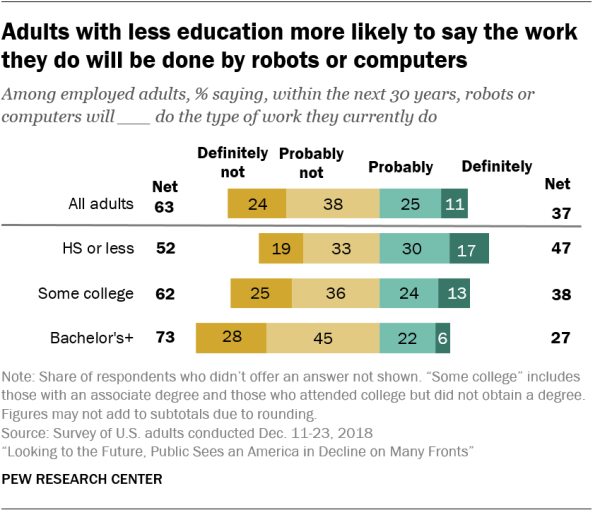

While only 37% of all currently employed Americans personally see automation as a direct threat to their current occupation, less well-educated workers are likelier than those with more formal schooling to say the type of work they do will be done by robots or computers in the future. About half (47%) of those with a high school diploma or less education say this change will occur compared with 38% of those with some college experience and 27% of those with a bachelor’s or advanced degree.

Most Americans agree that the workplaces of the future will be heavily automated. About eight-in-ten (82%) predict that robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans – a possibility that many adults with less education view with suspicion, if not outright dread. Among those who say robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans, about eight-in-ten of those with a high school diploma or less education say this would be a bad thing for the country (39% say it would be very bad; 39% say it would be somewhat bad). Those with a bachelor’s degree or more education are less fearful: Roughly six-in-ten say an automated workplace would be very (13%) or somewhat bad (45%).

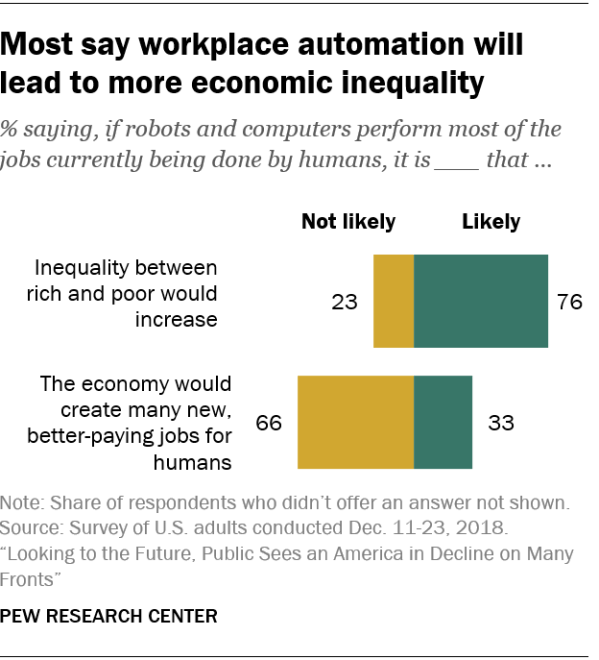

Regardless of educational background, most Americans predict that automation in the workplace will increase inequality between the rich and the poor and will not result in new, better-paying jobs.

Who will pay – and who should pay – for long-term eldercare in the future?

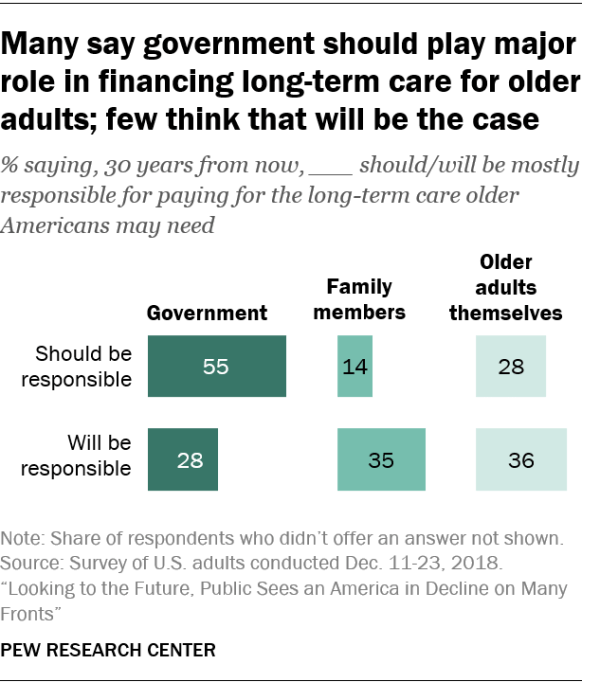

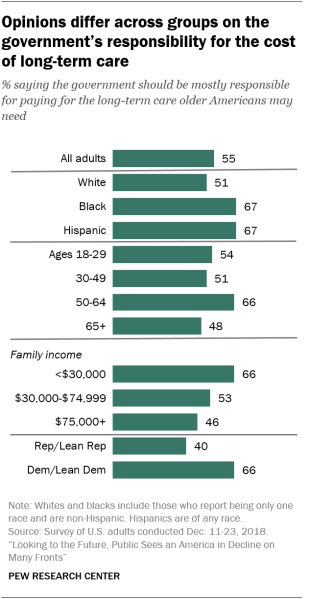

A slim majority of Americans (55%) say that government should be mostly responsible for paying for long-term care for older adults who need assistance in the future. But when asked who will be responsible for paying for this care in the future, only about half that share (28%) say the financial burden will fall on the government. Instead, about seven-in-ten predict that family members (35%) or older adults themselves (36%) will bear these costs.

Similar shares of most key demographic groups agree about who will pay the bills for long-term care in the future. But these groups often differ about who should be primarily responsible for the costs of this care. Two-thirds of blacks and Hispanics (67%) say government should be mostly responsible for paying for long-term care for older adults, while about half of whites (51%) agree. Similarly, two-thirds of adults ages 50 to 64 say government should be mostly responsible for this care compared with about half of all other age groups, including those 65 and older. In addition, two-thirds of Americans with family incomes under $30,000 look to government to cover the cost, compared with about half of those with higher incomes.

Democrats see a bigger role than Republicans for the government in paying for long-term elder care (66% vs. 40%). On the other hand, Republicans are about twice as likely as Democrats to believe older adults themselves should be primarily responsible for paying for their care (40% vs. 21%). Relatively few Democrats (11%) or Republicans (18%) say the responsibility should fall mainly to family members.

Predictions about the future of marriage, divorce and childbearing differ by race

Overall, about half of adults (53%) say that, by 2050, people will be less likely to get married than they are today. Very few (7%) predict that people will be more likely to marry in the future, and 39% say things will stay about the same. Whites and Hispanics are much more likely than blacks to predict lower marriage rates in the future – 56% of whites and 53% of Hispanics say people will be less likely to marry compared with 34% of blacks. Blacks are the only group in which a majority say marriage rates will stay the same or increase. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, blacks are significantly less likely than whites or Hispanics to be married. Among those ages 18 and older, 31% of blacks were married in 2017 compared with 46% of Hispanics and 54% of whites.2

Predictions about the future of divorce reveal a somewhat different pattern. More than six-in-ten whites (64%) but half of blacks and 42% of Hispanics expect people will be about as likely to get divorced in 2050 as they are today. In this regard, Hispanics are more pessimistic than whites about the future state of marriage: 37% predict that people will be more likely to divorce in the future, compared with 27% of whites and 30% of blacks.

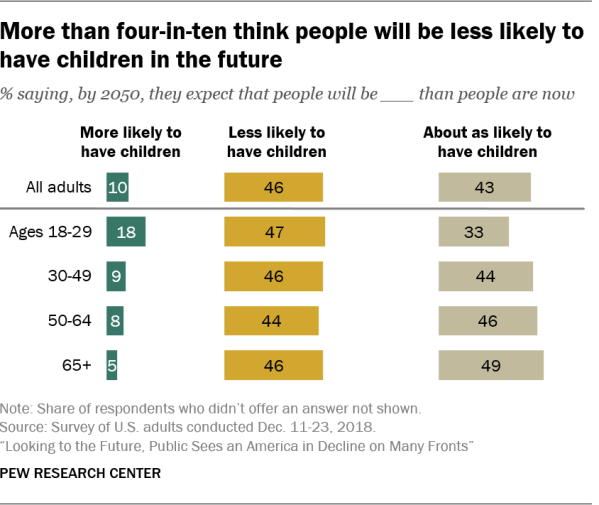

More than four-in-ten Americans (46%) expect that, by 2050, people will be less likely to have children than they are now. A similar share (43%) think people will be about as likely to have children, while just one-in-ten expect people to be more likely to have children in the future. Young adults are more likely than older Americans to say this is the case. Even so, only 18% of those ages 18 to 29 say they expect that people in 2050 will be more likely to have children, compared with 9% of adults 30 to 49 and 7% of those ages 50 and older.

America in 2050

Americans are narrowly hopeful about the future of the United States over the next 30 years but more pessimistic when the focus turns to specific issues, including this country’s place in the world, the cost of health care and the strength of the U.S. economy.

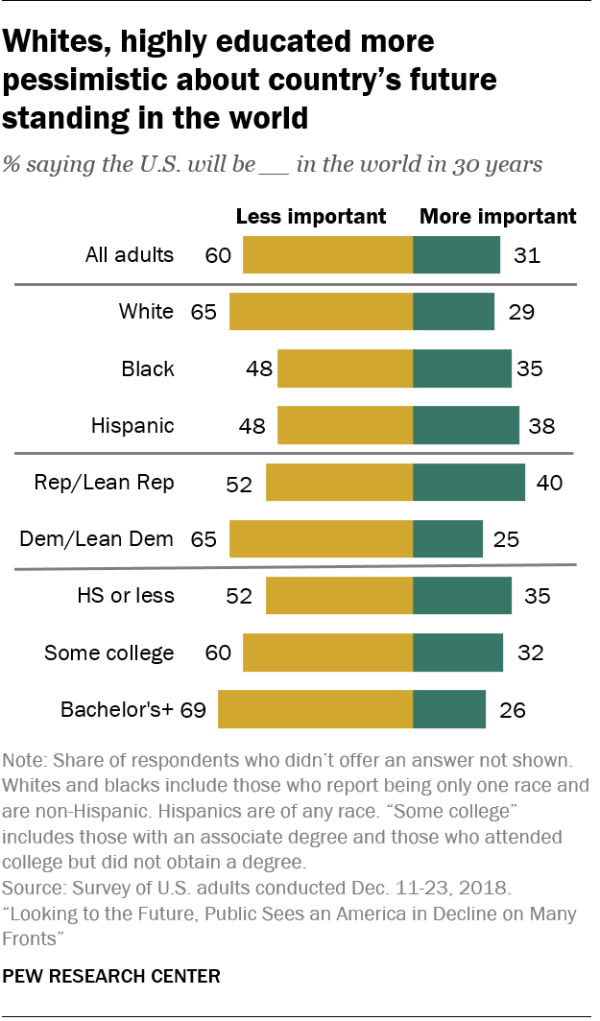

Overall, six-in-ten adults predict that that the U.S. will be less important in the world in 2050. While most key demographic groups share this view, it is more widely held by whites and those with more education. About two-thirds of whites (65%) forecast a diminished role in the world for the U.S. in 30 years, a view shared by 48% of blacks and Hispanics. Roughly seven-in-ten adults with a bachelor’s or higher degree (69%) see a lesser role internationally for America. By contrast, six-in-ten of those with some college education (but no bachelor’s degree) and 52% of those with less education are as pessimistic about the country’s future world stature.

The current partisan political debate over the country’s proper role in the world is mirrored in these results. About two-thirds of Democrats and independents who lean Democratic (65%), but closer to half of Republicans and Republican leaners (52%), think America will be a diminished force in the world in 2050. These differences are even greater among partisans at opposite ends of the ideological scale: 72% of self-described liberal Democrats but 49% of conservative Republicans say the U.S. will be less important internationally in 30 years.

As they see the importance of the U.S. in the world receding, many Americans expect the influence of China will grow. About half of all adults (53%) expect that China definitely or probably will overtake the United States as the world’s main superpower in the next 30 years. As with U.S. standing in the world, large party differences emerge on this question. About six-in-ten Democrats (59%) but just under half of Republicans (46%) predict that China will supplant the U.S. as the world’s main superpower.

The public predicts another 9/11 – or worse – by 2050

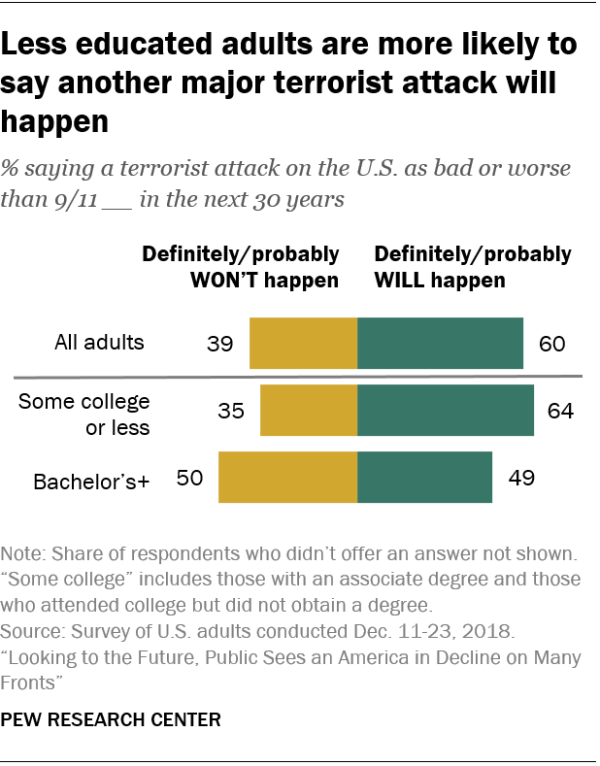

For an overwhelming majority of Americans, the 9/11 terrorist attacks stand as the most important historic event in their lifetimes. As Americans look ahead to 2050, six-in-ten say that a terrorist attack on the U.S. as bad or worse than 9/11 will definitely (12%) or probably (48%) happen.

This troublesome prediction is widely expressed by most major demographic groups. Roughly equal proportions of whites (61%), blacks (56%) and Hispanics (59%) say such a terrorist attack is likely sometime in the next 30 years, and so do 57% of men and 62% of women. While Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say such an attack will definitely or probably happen, majorities in each group express this view (63% of Republicans and 57% of Democrats).

At the same time, some demographic differences do emerge. Those with some college or less education are more likely than college graduates to expect another 9/11 (64% vs. 49%) by 2050. And Americans who are 50 or older are more likely than younger adults to say this will happen.

Narrow majority sees a weaker economy in 2050

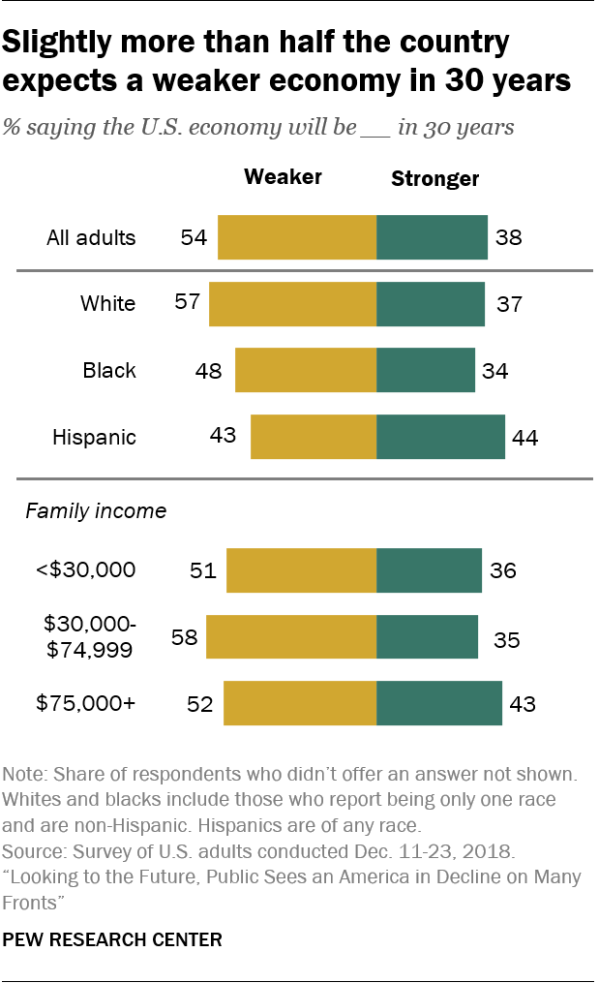

Just over half of the public (54%) predicts that the U.S. economy in 30 years will be weaker than it is today, while 38% say it will be stronger. Similarly, larger shares of most key demographic groups forecast a less robust rather than a more vigorous economy in 2050.

Whites are somewhat more pessimistic than blacks or Hispanics about the future financial health of the country: 57% of whites compared with 48% of blacks and 43% of Hispanics predict a weaker economy in 30 years.

Roughly half or more of every income group predict a weaker economy in the next 30 years. However, Americans in higher-earning families are somewhat more likely than lower-earners to say the economy will be better in 2050 than it is today. About four-in-ten adults (43%) with family incomes of $75,000 or higher say the economy will be stronger, a view shared by 35% of those earning less.

The partisan divides on views about the future of the economy are substantial. Roughly six-in-ten Democrats (58%) predict a weaker economy in 2050, while a third say it will be stronger. By contrast, Republicans are divided: 49% forecast a worsening economy, but 45% expect economic conditions to improve over the next 30 years.

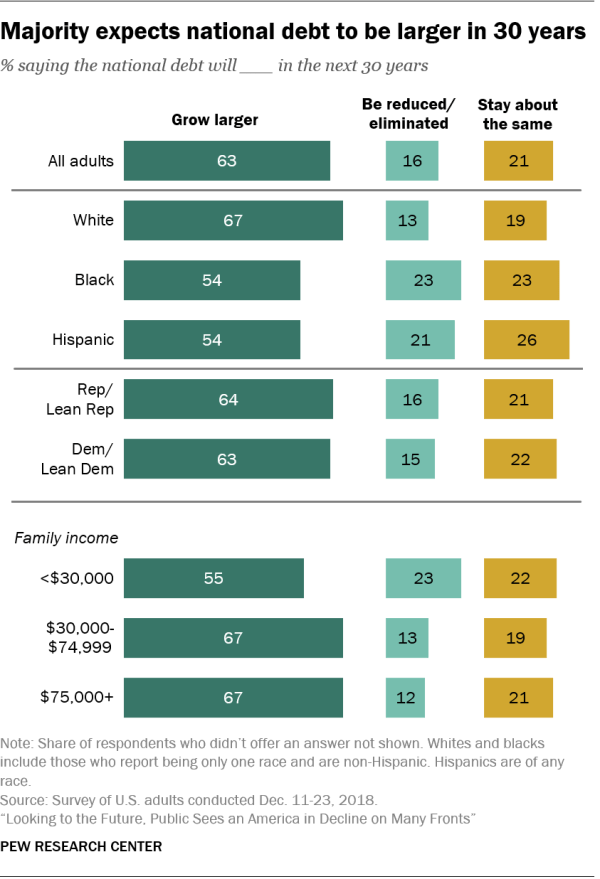

The public is also pessimistic about the future course of the national debt. About six-in-ten (63%) say the national debt – the total amount of money the federal government has borrowed – will increase, while just 16% predict it will be reduced or eliminated. Two-in-ten (21%) say it will stay relatively unchanged from what it is today.

These predictions of a growing government debt are consistent with recent history. According to the Congressional Budget Office, the federal debt held by the public is projected to reach 78% of the U.S. gross domestic product in 2019 – up from 34% in 2000.

Similar to projections about the overall economy, virtually every key demographic group is more likely to predict that government debt will grow larger than to predict it will shrink. Higher- and middle-income adults are more likely than those with lower incomes to expect the debt to rise: 67% of Americans with family incomes of $30,000 or more say the debt will grow larger by 2050, compared with 55% of those with incomes under $30,000. Whites also are more likely than blacks or Hispanics to say the national debt will rise (67% vs. 54% for both blacks and Hispanics). At the same time, virtually identical shares of Republicans (64%) and Democrats (63%) forecast a growing national debt.

Among the other looming threats to the U.S. economy: a major worldwide energy crisis, which two-thirds of the public say will definitely (21%) or probably (46%) occur in the next 30 years. While substantial majorities of every major demographic group predict a global power emergency, Hispanics and lower-income adults are particularly likely to see this occurring. About three-quarters of Hispanics (76%) and adults with family incomes of less than $30,000 (73%) expect a major energy crisis in the next 30 years. By contrast, 64% of whites and 60% of those with household incomes of $75,000 or more share this pessimistic view.

Differences on this question between political partisans are particularly large. About three-quarters (76%) of Democrats but 55% of Republicans expect a serious global energy crisis in the next 30 years.

Public predicts growing income inequality and an expanding lower class

About three-quarters of all Americans (73%) expect the gap between the rich and the poor to grow over the next 30 years, a view shared by large majorities across major demographic and political groups.

Differences between some groups do emerge, but only the size of the majorities differ and not the underlying belief that income inequality will grow. About three-quarters of whites (77%) but smaller majorities of blacks (62%) and Hispanics (64%) expect income inequality to increase by 2050. Similarly, about three-quarters of those who attended or graduated from college (77%) say the gap between the rich and the poor will increase, a view shared by two-thirds of those with a high school diploma or less education. Roughly equal shares of Republicans and Democrats expect income inequality to grow (71% and 75%, respectively).

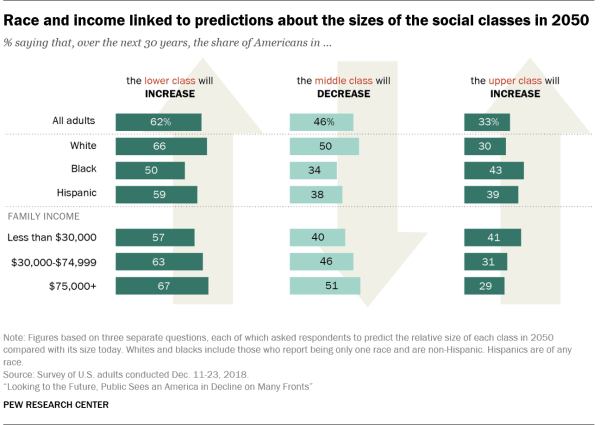

The growing rich-poor gap is not the only cloud the public sees on the economic horizon. About six-in-ten Americans (62%) say the share of people in the lower class will increase by 2050. At the same time, just under half (46%) predict that the relative size of the middle class will shrink, while 28% say it will grow larger, and about the same share (26%) say it will not change.

Americans are less certain about future changes in the share of Americans in the upper class. The predominant expectation is that the upper class will remain about the same relative size that it is today, a view held by 44% of the public. A larger share predicts that the proportion of Americans in the upper class will increase than say it will get smaller (33% vs. 22%).

Race and family income are closely associated with these views. Whites are significantly more likely than blacks to predict that the relative size of the lower class will increase (66% vs. 50%) and that the middle class will shrink (50% vs. 34%). Whites are less likely than blacks to say the upper class will grow (30% vs. 43%). Hispanics’ views on the future of the lower class are similar to those of whites and blacks, but in their perceptions of the future relative size of the middle and upper classes, Hispanics are closer to blacks (38% say the middle class will get smaller; 39% predict the upper class will increase).

Regardless of their income category, majorities of Americans predict that the size of the lower class will increase as a share of the total population. But those closer to the top of the income ladder are somewhat more likely to forecast a growing lower class than those who are closer to the bottom. Two-thirds (67%) of Americans with annual family incomes of $75,000 or more say the lower class will grow, a view shared by 57% of those with incomes of $30,000 or less. Higher-earners also are more likely than those with less family income to say the relative size of the middle class will shrink (51% vs. 40%). At the same time, Americans with a family income of $75,000 or more are less likely than those with annual family incomes under $30,000 to expect a larger share of Americans to be in the upper class in 2050 (29% vs. 41%).

Partisan differences on these questions are relatively modest. Democrats are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say that the share of Americans in the lower class will grow (65% vs. 59%) and the middle class will shrink (50% vs. 42%). About a third of both parties predict that the relative size of the upper class will increase.

Divided views on the future of race relations but some hopeful signs

The public is uncertain whether the troubled state of race relations today will still be a feature of American life in 2050. About half (51%) say race relations will improve over the next 30 years, but 40% predict that they will get worse.

Unlike the large differences that mark views of blacks and whites on many race-related questions, the racial divide on this question is narrower. A slight majority of whites (54%) predict that race relations will improve in the next 30 years, while 39% say they will worsen. Blacks split down the middle: 43% predict better relations between the races and the same percentage predict they will be worse. Hispanics also split roughly equally, with 45% expecting improved relations and 42% saying they will get worse.

Optimism about the future of race relations is closely related to educational attainment. Six-in-ten adults with a bachelor’s or higher degree predict that race relations will improve. By contrast, 47% of those with less education are hopeful about the future of race relations.

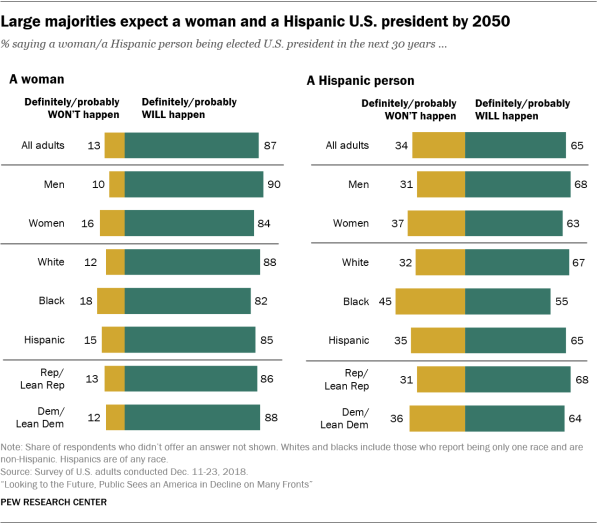

Other findings suggest the public thinks barriers that have blocked some groups from leadership positions in politics may ease in the future. Nearly nine-in-ten (87%) predict that a woman will be elected U.S. president by 2050 (30% say this will definitely happen; 56% say it probably will). And roughly two-thirds (65%) expect that a Hispanic person will lead the country sometime in the next 30 years (13% definitely; 53% probably).

Expectations of a female president are broadly shared. Eight-in-ten or more men and women, whites, blacks and Hispanics, and Republicans and Democrats predict there will be a woman in the White House by 2050. Roughly two-thirds of whites (67%) and Hispanics (65%) and 55% of blacks say that a Hispanic person will be president; Hispanics (23%) are more likely than whites (11%) or blacks (7%) to say this will definitely happen.

Few Americans predict a higher standard of living for families, older adults or children in 2050

When Americans predict what the economic circumstances of the average family will be in 2050, they do so with more trepidation than hope. More than four-in-ten (44%) predict that the average family’s standard of living will get worse over the next 30 years, roughly double the share who expect that families will live better in 2050 than they do today. About a third (35%) predict no real change.

Women are somewhat more likely than men to think the average family’s standard of living will erode over the next 30 years. Some 47% of women are pessimistic about the economic future of families, while only 16% are optimistic. By contrast, 42% of men expect the typical family’s standard of living to be worse, while a quarter say it will improve.

While comparatively few Americans predict a better standard of living for families, minorities are somewhat more likely than whites to be optimistic. About a quarter of blacks (25%) and Hispanics (24%) say the average family’s standard of living will be higher in 2050 than it is today, compared with 17% of whites. And while nearly half of all whites predict things will get worse for families, only about a third of Hispanics (35%) are as pessimistic.

When younger adults look ahead to 2050, they are more likely than their older counterparts to see a brighter future for America’s families. About three-in-ten (28%) of adults ages 18 to 29 but 19% of those age 30 and older say the average family’s standard of living will get better over the next three decades. Still, about a third (36%) of 18- to 29-year-olds predict harder times ahead for families compared with 46% of those ages 30 and older.

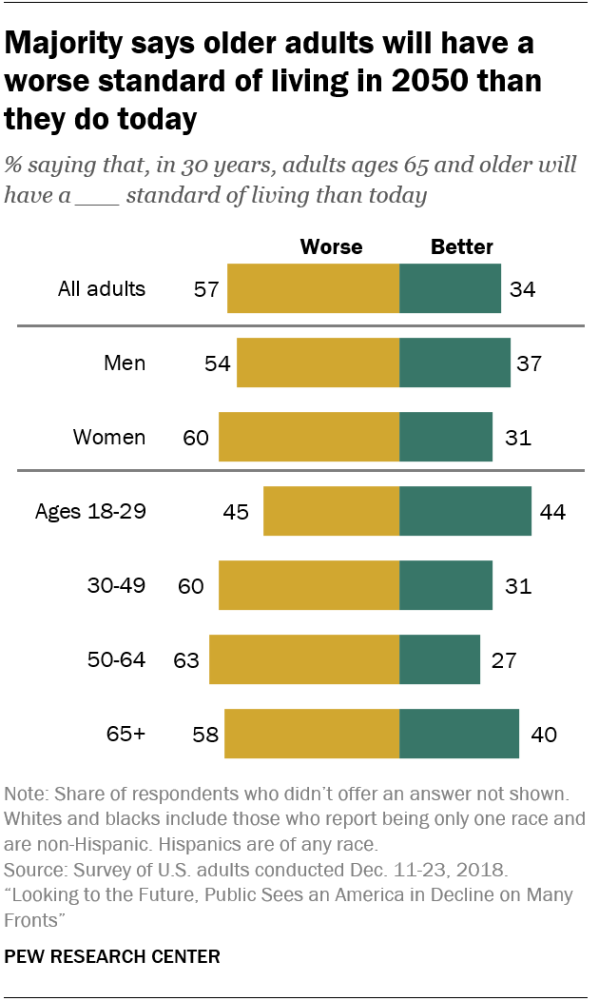

The public also is broadly pessimistic about the economic fortunes of older Americans during the next 30 years. A 57% majority says adults ages 65 and older will have a worse standard of living in 2050 than today. The public is somewhat less negative about the economic prospects of children; half say children will have a worse standard of living in 30 years than they do today, while 42% predict that their standard of living will improve.

When it comes to the future economic prospects of older adults, young adults and those ages 65 and older are more upbeat than their middle-aged counterparts: 44% of those ages 18 to 29 and 40% of those 65 and older say older adults will have a better standard of living 30 years from now, compared with 31% of those ages 30 to 49 and 27% of those 50 to 64.

The public does see at least one bright spot ahead for older Americans. About six-in-ten (59%) expect that a cure for Alzheimer’s disease will definitely or probably be found by 2050. Adults ages 65 and older are among the most optimistic about this: 70% expect an Alzheimer’s cure in the next 30 years. By contrast, about half (53%) of those younger than age 30 predict such a breakthrough.

However, the public is broadly pessimistic about the trajectory of health care costs over the next 30 years. Nearly six-in-ten (58%) predict health care will be less affordable in 2050 than it is today, a view shared across most demographic groups.

Worries, Priorities, and Potential Problem-Solvers

When Americans look to the future, they see threats on multiple fronts. Majorities are at least somewhat worried about moral values, climate change, the state of our public schools and the soundness of our economic system. The public views providing quality, affordable health care to all Americans, increasing spending for education and reducing the national debt as some of the top policy priorities for the future. And, while these and other issues might benefit from government action, the public has little confidence in government’s ability to effectively address these issues. Instead, Americans look to science and technology as potential problem-solvers for the challenges the country will face.

There are deep divisions between Republicans and Democrats over which issues should take priority in the future and what role government should play. The parties are more united in their concern over the functionality of government.

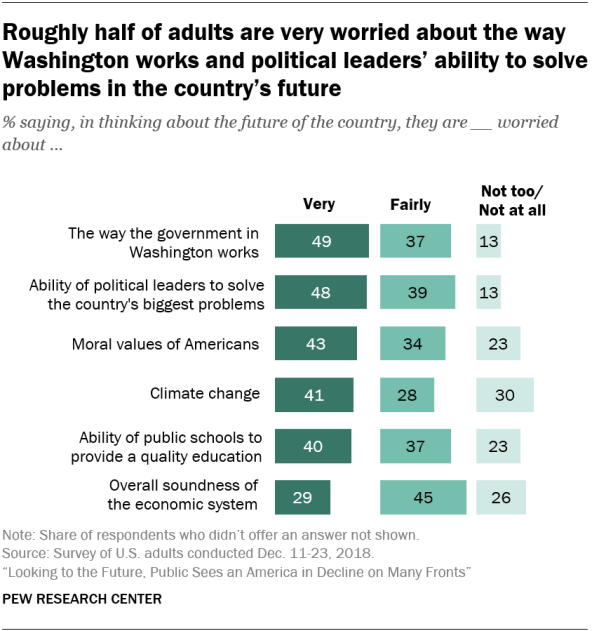

Overall, about half of all adults (49%) say, in thinking about the future of the country, they are very worried about the way the government in Washington works, and a similar share (48%) say they’re very worried about the ability of political leaders to solve the country’s biggest problems.

Public worry about the functionality of government is more widespread – and consistently held – than concern over moral values, climate change, the county’s public schools or the economic system. While Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are somewhat more likely than Republicans and Republican leaners to be very worried about the way the government in Washington works, a large share of those who identify with or lean to the GOP are also very worried about this, too (53% of Democrats vs. 45% of Republicans). Democrats are also more concerned than Republicans about the ability of political leaders to solve the country’s problems: 54% of Democrats and 40% of Republicans are very worried about this.

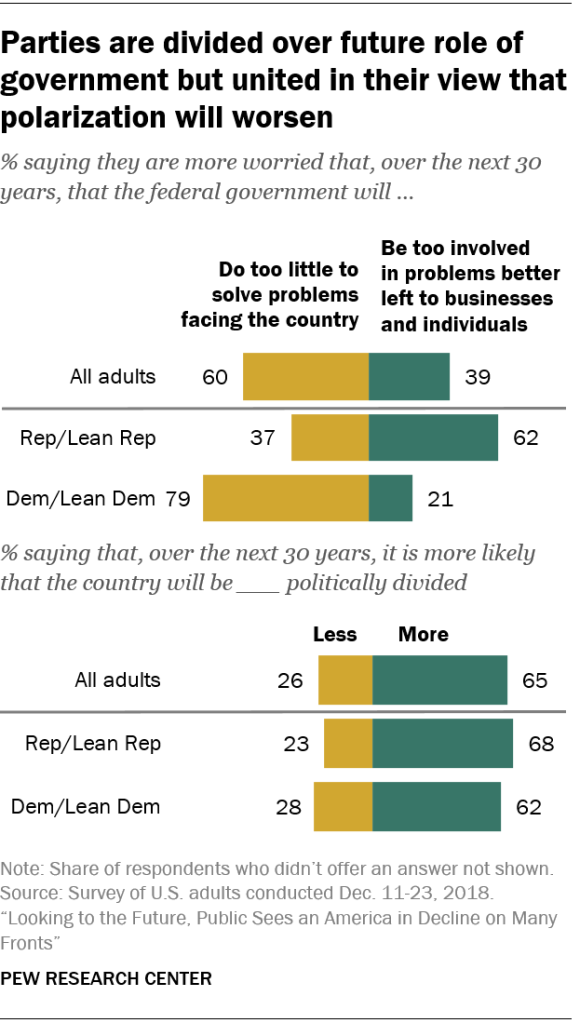

While some Americans are concerned about government overreach in the future, most say they worry the government won’t do enough to address the country’s problems. Six-in-ten say they worry more that, over the next 30 years, the federal government will do too little to solve the problems facing the country, while 39% say they worry the government will be too involved in problems that should be left to businesses and individuals.

These views are strongly linked to partisanship. Among Democrats, 79% say they are more worried that the government will do too little to solve problems, while 21% say they worry that the government will be too involved in solving problems. By contrast, a majority of Republicans (62%) say they worry about government doing too much rather than too little (37%).

Not only does the public worry about the government’s ability to solve national problems, most Americans think the partisan polarization that characterizes today’s politics will worsen in the future. Roughly two-thirds (65%) of all adults predict that, in 2050, the country will be morepolitically divided than it is now, while only about a quarter (26%) say it will be less polarized. This is the majority sentiment across most major demographic groups and across parties – 68% of Republicans and 62% of Democrats say the country will be more politically divided in the future.

The belief that the country will be more politically divided is strongly linked with worry about the government’s ability to solve the nation’s problems. Among those who say the country will be more divided in 30 years, 54% say they are very worried about the ability of political leaders to solve the country’s biggest problems. Those who see less political division are less worried about politicians’ ability to get things done: 37% of those who say the country will be less politically divided in the future also say they are very worried about political leaders taking on important national problems.

Looking to the future, about four-in-ten Americans are very worried about moral values, climate change and the nation’s public schools

Roughly four-in-ten Americans (43%) say they are very worried about the moral values of Americans in the future. Similar shares are very worried about climate change (41%) and about the ability of public schools to provide a quality education (40%). Concern about moral values and climate change is strongly linked to partisanship, while worry over the state of public schools cuts across party lines.

For Republicans, morality is a top-tier concern. Roughly half (49%) say, when they think about the country’s future, they are very worried about the moral values of Americans. Democrats (36%) are less likely to be very worried about this. Women are more concerned about the country’s morals than men (46% vs. 38%), and there is a significant age gap as well: Among adults ages 50 and older, about half (49%) say they are very worried, compared with 37% of those younger than 50.

Across major religious groups, white Evangelical Protestants are the most worried about the country’s moral values: 59% say they are very worried compared with 43% of white mainline Protestants, 44% of black Protestants and 43% of white, non-Hispanic Catholics. Adults who say they are atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular are significantly less worried about this (33% very worried).

When it comes to the future of religion in the U.S., the public is divided over whether religion will become less important over the next 30 years (50% say it will) or whether it will remain about as important as it is now (42% say this). Roughly equal shares of white Evangelicals (52%), white mainline Protestants (51%), white Catholics (54%) and those who are atheist, agnostic or nothing in particular (59%) say religion will be less important in the future. There’s no correlation between a belief that religion will be less important in the future and being very worried about the country’s moral values.

The level of concern over climate change is similar to that of moral values, but this concern is concentrated among a much different constituency. Young adults are more likely than their older counterparts to say they are very worried about this. Among those ages 18 to 29, 52% are very worried; this compares with 41% of those ages 30 to 49 and 37% of those ages 50 and older. The partisan gap is even wider: Democrats are about four times as likely as Republicans to say they are very worried about climate change (61% vs. 15%).

Thinking more generally about the overall condition of the environment in the future, a majority of Americans are pessimistic. About six-in-ten (59%) say the condition of the environment will be worse than it is now by the year 2050, 16% say it will be better and 25% say it will stay about the same. Again, Democrats and Republicans have very different views: 70% of Democrats say the environment will be worse by 2050, while only 43% of Republicans say the same.

The public’s pessimism and sense of worry about the future extends to their outlook on the state of the nation’s public schools. Four-in-ten Americans say they are very worried about the ability of public schools to provide a quality education in the future, and an additional 37% say they are fairly worried. Concern about public education cuts across major demographic groups and across party lines. Roughly equal shares of Democrats (38%) and Republicans (41%) say they are very worried about the ability of public schools in the future to provide a good education.

Similarly, only about four-in-ten Americans (38%) say the public education system will improve over the next 30 years, while 52% say it will get worse. Young adults are somewhat more optimistic than their older counterparts about the future of public schools: Among those ages 18 to 29, about half (48%) expect the education system will improve, while only 36% among older age groups say the same.

Fewer Americans are anxious about the overall soundness of the country’s economic system. Roughly three-in-ten adults (29%) say they are very worried about this, and 45% are fairly worried. Adults from lower-income households express more concern than those in middle- and upper-income households: 34% of those with an annual family income of less than $30,000 say they are very worried about this compared with 27% of those earning $30,000-$74,999 and 22% of those earning more than $75,000. In addition, Democrats are more worried about the future of the economic system than Republicans – 32% vs. 21%, respectively, are very worried.

Most say providing health care for all would improve the lives of future generations

When Americans think about what the federal government could do to improve the quality of life for future generations, their top priorities tend to involve more government spending, although many also place a high premium on reducing the national debt. About two-thirds (68%) of adults say providing high-quality, affordable health care to all Americans should be a top priority for the federal government to improve the lives of future generations. A slight majority (54%) ranks increased spending for education as a top priority, and nearly as many (47%) say the same about increased spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. At the same time, 49% say reducing the national debt should be a top government priority.

Democrats and Republicans have much different visions of what government should do to improve the lives of future generations. For Democrats, the federal government’s top priorities should be providing high-quality, affordable health care to all Americans (83% say this should be a top priority), dealing with climate change (69%), increasing spending for education (66%), reducing the gap between the rich and the poor (58%) and increasing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid (56%).

For Republicans, the most important steps government should take to improve the lives of future generations include reducing the number of undocumented immigrants coming into the U.S. (65% say this should be a top priority), reducing the national debt (57%) and avoiding tax increases (50%). Many Republicans also prioritize providing health care to all Americans (48%) and increasing spending for education (36%) over other issues but by much smaller shares than Democrats.

Modest support for increasing government spending on infrastructure, scientific research and military

Overall, the public is less supportive of increasing government spending in other areas. About a third of adults (36%) say increasing spending for roads, bridges and other infrastructure should be a top priority for government in the future. A similar share (34%) say increasing spending on scientific research should be a top priority. And roughly one-in-four (23%) say increasing military spending should be a top priority.

Democrats are more likely than Republicans to say infrastructure spending and investments in scientific research should be top government priorities. Just the opposite is true for military spending. Republicans are more than twice as likely as Democrats to say increasing military spending should be a top priority in the future (36% vs. 13%). By contrast, Democrats are more likely to say reducing military spending should be a top priority; 36% of Democrats say this vs. 8% of Republicans.

There is relatively little public support for reducing government spending in other areas to improve the quality of life for future generations. Only one-in-five adults say reducing spending on Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid should be a top government priority in the future, and 14% say reducing spending on roads, bridges and other infrastructure should be a top priority.

When it comes to immigration, 17% of adults say allowing moreimmigrants into the U.S. who come here legally should be a top priority for the federal government. Democrats are more likely to prioritize this than Republicans (22% vs. 10%).

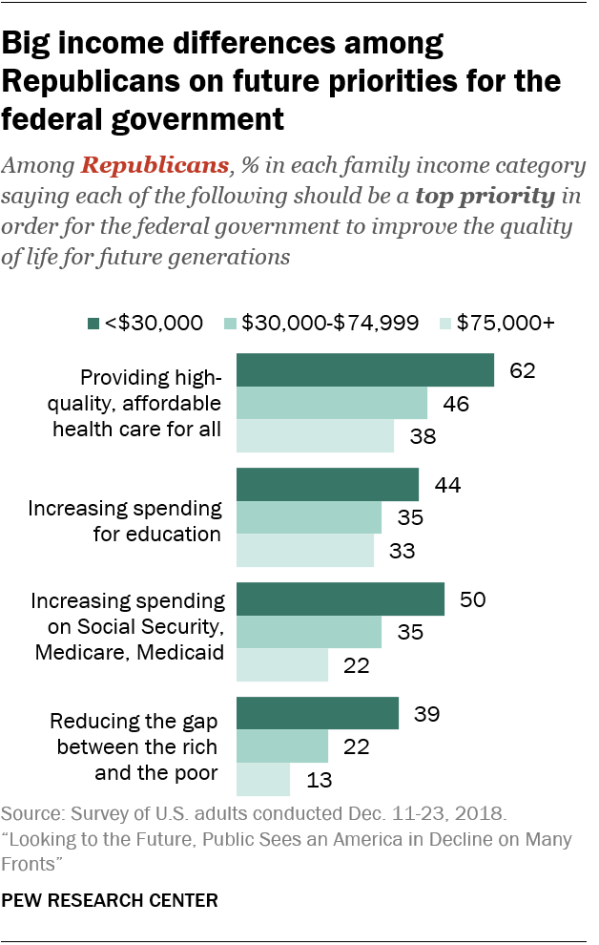

In addition to the partisan gaps, there are significant differences in priorities across income groups. Lower-income adults are much more likely than their middle- and higher-income counterparts to say providing health care to all Americans, increasing spending on education and entitlement programs and reducing the gap between rich and poor should be top government priorities.

These gaps are driven in large part by differences among Republicans. For example, among Republicans with an annual family income of less than $30,000, 62% say providing affordable health care to all Americans should be a top priority in order to improve the quality of life for future generations. Among Republicans with incomes between $30,000 and $74,999, 46% say affordable health care should be a top priority, and, among those with incomes of $75,000 or higher, 38% say the same. The pattern is similar on views about spending on education and entitlement programs and reducing the gap between the rich and the poor.

Public sees future promise in science and technology, few have faith in government’s ability to solve problems

Although most Americans don’t place a high priority on increased spending on scientific research, many see science and technology as a force for positive change in the future. When asked what kind of impact a range of institutions – including federal, state and local governments – will have on solving the biggest problems facing the country in the future, the public views science and technology as potentially having a greater impact than the others.

About four-in-ten adults (43%) say science and technology will have a very positive impact in the future on solving the nation’s problems. An additional 44% say science and technology will have a somewhat positive impact. Democrats have more faith than Republicans in science and technology’s ability to help solve problems: 52% of Democrats but 31% of Republicans say these institutions will have a very positive impact in the future. In addition, those with a bachelor’s degree or more education have a more positive view of science and technology than do those with less education (50% and 39%, respectively, say these will have a very positive impact).

In contrast with the faith Americans have in the potential for science and technology, they have very little confidence in government’s ability to tackle the country’s biggest problems. Only 7% say they think the government in Washington will have a very positive impact on solving the nation’s problems in the future; 37% say the federal government will have a somewhat positive impact. More than half say government will have either a somewhat negative impact (36%) or a very negative impact (19%).

The public has more confidence in state and local government: 11% say these entities will have a very positive impact in terms of solving the country’s problems, and 52% say they will have a somewhat positive impact.

Democrats and Republicans are generally in agreement about the impact the federal government will have in the future. Only 5% of Republicans and 8% of Democrats think the government will have a very positive impact. On balance, Republicans and Democrats are more likely to say the government in Washington will have a negative impact in terms of addressing the country’s biggest problems in the future than they are to say it will have a positive impact. Both parties have a more positive view of the potential impact of state and local governments.

Public views educational institutions having a positive impact in the future, news media having a negative impact

One-in-four Americans say they think, in the future, public K-12 schools will have a very positive impact in solving the biggest problems facing the country; an additional 53% say public schools will have a somewhat positive impact. Assessments of colleges and universities are similar: 24% say they will have a very positive impact and 50% say somewhat positive.

There are large party gaps in views about the potential impact of educational institutions, particularly when it comes to higher education. Some 87% of Democrats say colleges and universities will have a positive impact (either very or somewhat) in terms of helping to solve the country’s problems; only 56% of Republicans say the same. This echoes earlier findings showing a partisan gap in views about whether the higher education system is generally going in the right or wrong direction. Democrats are also more likely than Republicans to say public K-12 schools will have a positive impact on the country’s future (86% vs. 66%).

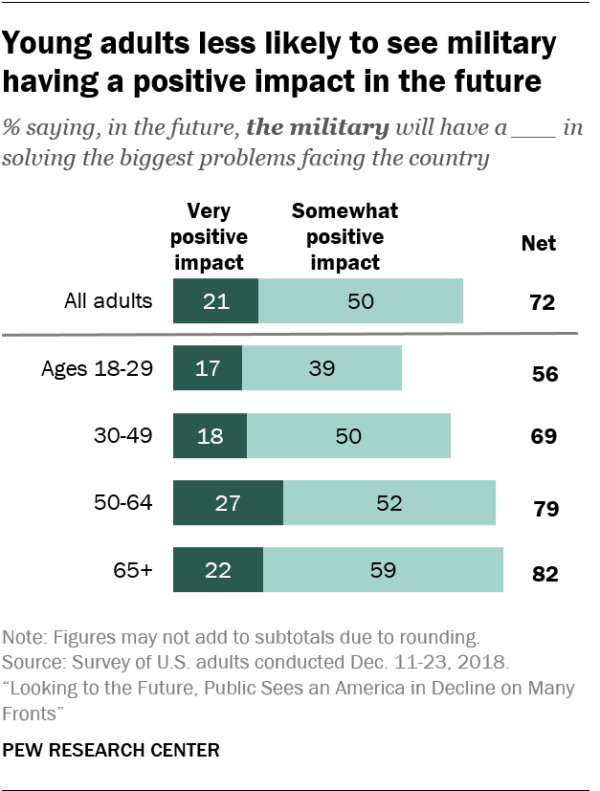

About one-in-five Americans (21%) say the military will have a very positive impact in solving big problems the future, and an additional 50% say it will have a somewhat positive impact. Republicans are twice as likely as Democrats to see the military having a very positive impact (30% vs. 15%). There’s a significant age gap as well, with younger adults expressing less confidence in the military than their older counterparts. While 56% of adults ages 18 to 29 say the military will have either a very or somewhat positive impact in the future, in terms of helping address the country’s biggest problems, 69% of those ages 30 to 49 predict that the military will have a positive impact, and the share rises to roughly eight-in-ten among adults 50 and older.

On balance, the public sees religious groups as having a more positive than negative impact on finding solutions to national problems in the future, but relatively few (15%) think these groups will have a very positive impact. Not surprisingly, adults with a high level of religious commitment are much more likely than those who are less committed to religion to say that religious groups will have a positive impact in the future.3

The public is divided over the impact major corporations will have in solving future problems. About half (51%) say corporations will have a positive impact (9% very positive, 41% somewhat positive), and 48% say they will have a negative impact (16% very negative, 32% somewhat negative). The balance of opinion on this is different among Republicans and Democrats. A majority of Republicans (61%) say corporations will have a positive impact, while 37% say they will have a negative impact. Democrats lean in the opposite direction: 57% say the impact of corporations in the future will be negative, 42% say positive.

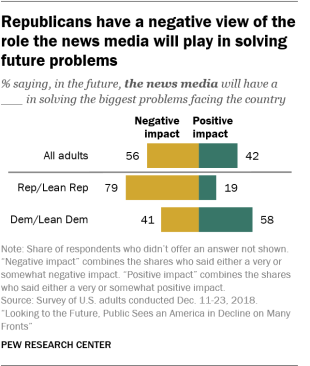

The public predicts the future impact of the news media will be more negative than positive (56% vs. 42%). There’s a wide party gap on this issue: Republicans overwhelmingly say the news media will have a negative impact in terms of solving the nation’s problems in the future – 79% say this, including 45% who say the media will have a very negative impact. Among Democrats, 58% say the media will have a positive impact in the future, while 41% say the impact will be negative.

Previous research has shown that the partisan gap in views on the current impact of some institutions has widened in recent years, particularly colleges and universities and the news media.

Views of Demographic Changes

As the U.S. population becomes more racially and ethnically diverse, Americans have mixed views about how the country might change when blacks, Hispanics, Asians and other minorities make up a majority of the population. While more say this change will be good for the country than say it will be bad, the predominant view is that it will be neither.

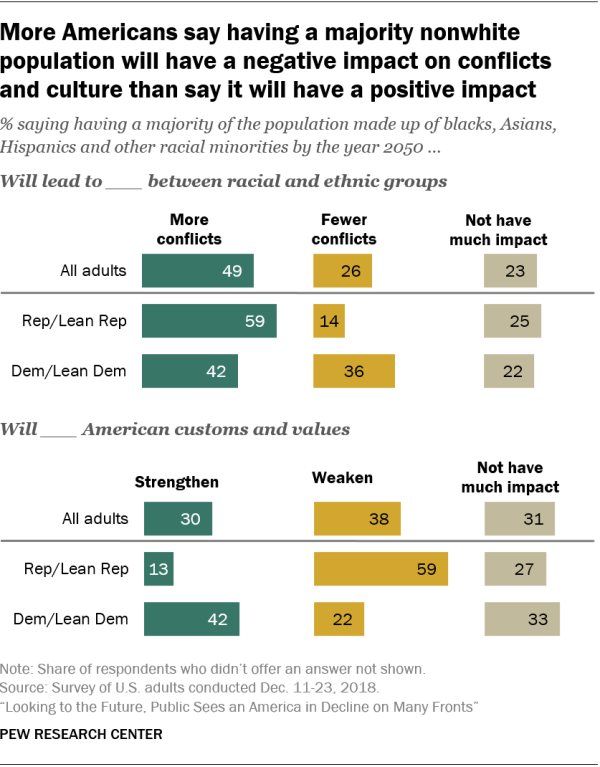

At the same time, when asked about projections by the U.S. Census Bureau that a majority of the U.S. population will be nonwhite by the year 2050, about half of Americans say this shift will lead to more conflicts between racial and ethnic groups. And about four-in-ten predict that a majority nonwhite population will weaken American customs and values, larger than the shares who say it will strengthen them (30%) or will not have much of an impact (31%).

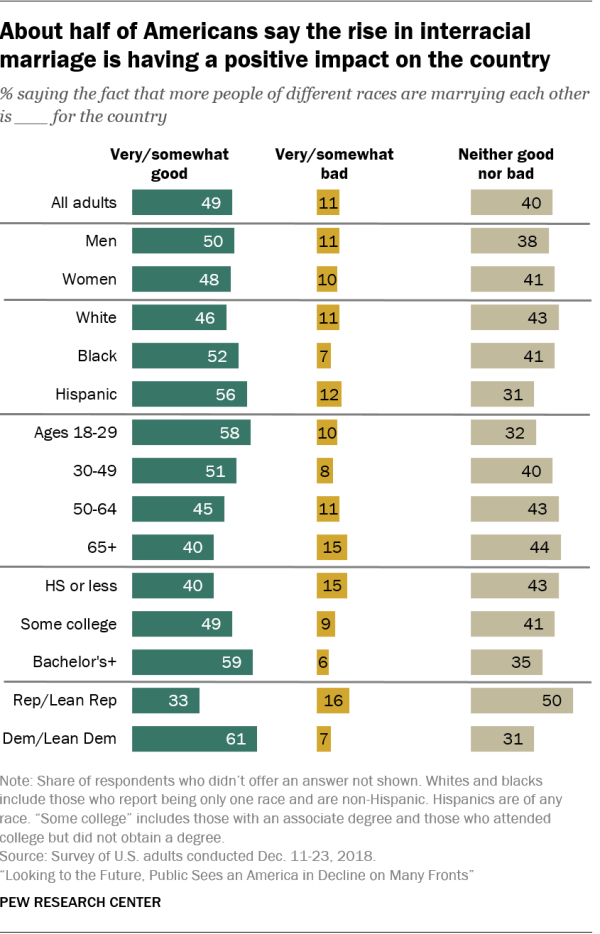

Opinions about the growth in interracial marriage are, on balance, positive or neutral. About half say more people of different races marrying each other than in the past is a somewhat or very good thing for the country, while about one-in-ten say it’s a somewhat or very bad thing, and four-in-ten see this as neither good nor bad. On this question, as well as the questions about the impact of having a majority nonwhite population, Democrats and those who lean Democratic express far more positive views than Republicans and Republican leaners.

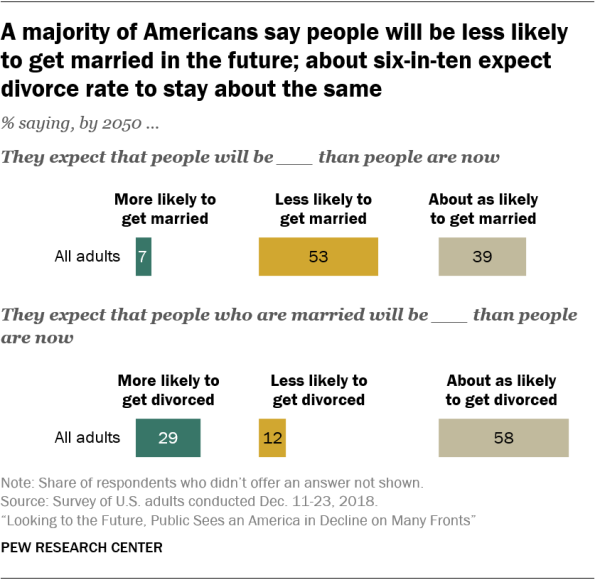

The survey also asked about trends related to marriage and divorce. About half of Americans (53%) predict that in 30 years people will be less likely to get married than they are now; just 7% say people will be more likely to get married, and 39% say people will be about as likely to marry. About six-in-ten expect the divorce rate to remain about the same, but 29% say people who are married will be more likely to get divorced than people are now; 12% say married people will be less likely to divorce.

Americans have a more negative view of another demographic trend: the aging of the U.S. population. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, by the year 2050, people who are 65 and older will outnumber those younger than 18, and 56% of Americans say this will have a negative impact on the country.

Americans are divided on the overall impact of having a majority nonwhite population

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, blacks, Asians, Hispanics and other racial minorities will make up a majority of the population by the year 2050. When asked about the impact this change will have on the country, about a third of adults say this will be either very (17%) or somewhat (18%) good, about a quarter say it will be very (15%) or somewhat (8%) bad, and 42% say this change will be neither good nor bad.

Nonwhites are about twice as likely as whites to say having a majority nonwhite population will be good for the country: 51% of all nonwhite adults – including 53% of blacks and 55% of Hispanics – say this, compared with 26% of whites. About three-in-ten whites (28%) say this change will be bad for the country, while 46% say it will be neither good nor bad.

Views also differ by age. Young adults are more likely than their older counterparts to say a shift toward a majority nonwhite population will benefit the country: 50% of adults younger than 30 hold this view, compared with 36% of those ages 30 to 49, 29% of those 50 to 64, and a quarter of adults ages 65 and older. These differences reflect, in part, the fact that the younger group is more racially and ethnically diverse than the older groups. Age differences in views of this projected demographic change are more modest among whites.

Views about the impact of having a majority nonwhite population also vary considerably by party. Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, half say this change will have a positive impact on the country, while 37% say it will be neither positive nor negative, and just 12% say it will have a negative impact. By contrast, a larger share of Republicans and Republican leaners say this will be bad for the country (37%) than say it will be good (16%), while 47% say it will be neither good nor bad. These partisan differences hold up even after accounting for respondents’ race and ethnicity.

About half of Americans say having a majority nonwhite population will lead to more racial and ethnic conflicts

While most Americans say a majority nonwhite population will have a positive or neutral impact on the country, more say this shift will lead to more conflicts between racial and ethnic groups (49%) than say it will lead to fewer conflicts (26%). And more say this will weaken American customs and values (38%) than say it will strengthen them (30%).

Consistent with their more negative assessments of the overall impact of this demographic change, whites are more likely than nonwhites to say having a majority nonwhite population will lead to more racial and ethnic conflicts (53% vs. 43%) and that it will weaken American customs and values (46% vs. 24%).

Among Republicans, about six-in-ten say having a majority nonwhite population will lead to more conflicts between racial and ethnic groups and that it will weaken American customs and values (59% say each will happen). Democrats are more divided in these assessments. About four-in-ten Democrats (42%) say this will lead to more racial and ethnic conflicts, 36% say it will lead to fewer conflicts and 22% say it won’t have much of an impact. And while 42% of Democrats say having a majority nonwhite population will strengthen American customs and values, sizable shares say it will weaken them (22%) or not have much of an impact (33%).

Many see the rise in interracial marriages as a good thing

About half of Americans say it’s either a very (30%) or somewhat (19%) good thing that a larger share of people of different races are marrying each other than in the past; about one-in-ten (11%) say this is a bad thing, and four-in-ten say it’s neither good nor bad. Views on this question don’t vary considerably across racial and ethnic groups.

A majority of adults younger than 30 (58%) see the increase in interracial marriages positively. Among the older groups, 51% of those ages 30 to 49, 45% of those ages 50 to 64, and 40% of those 65 and older agree. About four-in-ten in each of the three groups say this is neither good nor bad, while relatively few see it as a bad thing.

Views also vary by educational attainment and party identification. Nearly two-thirds of adults with a postgraduate degree (65%) say the rise in interracial marriage is a good thing for the country, compared with 55% of those with a bachelor’s degree, 49% of those with some college education and 40% of adults with a high school diploma or less education.

Among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents, about six-in-ten (61%) say it’s a good thing that more people of different races are marrying each other, and this is particularly the case among those who describe their political views as liberal. About three-quarters of liberal Democrats (73%) say this is a good thing, compared with 51% of their moderate or conservative counterparts. Just 7% of all Democrats and Democratic leaners consider the rise in interracial marriage to be a bad thing, and 31% say it’s neither good nor bad.

Republicans and Republican-leaning independents are less likely than Democrats to see the increase in interracial marriages in a positive way: 33% say this is a somewhat or very good thing, while 16% see this as a somewhat or very bad thing, and half say it’s neither good nor bad. There are no significant differences in the views of Republicans who consider themselves conservative and those who say they are moderate or liberal.

More than half of Americans expect marriage to be less common by 2050

Despite a longer-term downward trend, the share of U.S. adults who are married has been relatively stable in recent years. But about half of Americans expect that to change, with 53% saying that people will be less likely to get married in 2050 than they are now. Just 7% say people will be more likely to get married, while 39% expect no significant change.

For the most part, views on the future of marriage don’t vary much across demographic groups, but higher shares of those who are currently married (57%) than those who are not married (48%) expect marriage to be less common by 2050. And while 56% of whites and 53% of Hispanics expect that people will be less likely to get married in 2050 than they are now, just about a third of black adults (34%) say the same.

For the most part, Americans expect the divorce rate to stay largely unchanged: 58% think married couples will be about as likely to get divorced by 2050 as they are now. But a sizable share (29%) think people who are married will be more likely to get divorced in another 30 years; 12% think divorce will be less common by then. Married and unmarried people have similar views on the future of divorce.

Many think people will be less likely to have children

More than four-in-ten Americans (46%) expect that, by 2050, people will be less likely to have children than they are now. A similar share (43%) think people will be about as likely to have children, while just one-in-ten expect people to be more likely to have children in the future.

While a minority across all age groups expect that people in 2050 will be more likely to have children, young adults are more likely than older Americans to say this is the case. About one-in-five adults younger than 30 (18%) say they expect that people in 2050 will be more likely to have children, compared with 9% of adults 30 to 49, 8% of adults 50 to 64 and 5% of those 65 and older.

A majority of Americans say population aging will have a negative impact

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that, by 2050, the number of people who are 65 and older will outnumber those younger than 18. A majority of the public (56%) say this transformation will be a somewhat or very bad thing for the country, 17% say it will be good and 26% say it will be neither good nor bad.

Adults with more education are more likely than those with less formal schooling to see population aging negatively. About two-thirds of those with a bachelor’s degree or more education (67%) say this will have an adverse impact on the country, compared with 56% of those with some college and 48% of high school graduates and those with less education.

Views about the impact of population aging also vary considerably by gender. Men are far more likely than women to say this change will be bad for the country (64% vs. 49%), while 20% of women – vs. 13% of men – say this trend will have a positive impact. Views don’t vary considerably by age, race and ethnicity, or party identification.

Retirement, Social Security, and Long-Term Care

Looking to the future, Americans are pessimistic about the financial health of older Americans. Most say that, 30 years from now, those ages 65 and older will be less prepared for retirement than their counterparts today. And, among those who have not yet retired, a large majority (83%) doubt that Social Security will provide benefits at current levels when they eventually retire. About as many predict that most people will have to work into their 70s in order to afford to retire.

The public has little confidence that the government, rather than family members or older adults themselves, will take responsibility for financing the care older adults may need. While 55% say the government should play this role in the future, only 28% say the government will be responsible for this.

There is widespread skepticism about the future solvency of the Social Security system. Among those who are not retired, about four-in-ten (42%) doubt they will receive any Social Security benefits when they leave the workforce, while an additional 42% say benefits will be provided but at a reduced level.

These views differ significantly by age. Roughly half of Americans (48%) who are younger than 50 expect to receive no Social Security benefits when they retire. By contrast, about three-in-ten (28%) of those who are 50 or older are similarly pessimistic. But, even among this older group, relatively few (23%) expect to receive Social Security benefits at current levels.

Democrats and Republicans are united in their skepticism about the future of Social Security. Among those who are not retired, identical shares from each party (42%) say they don’t expect to receive benefits when they stop working.

Amid doubts about the soundness of the Social Security system, most Americans reject the idea of reducing benefits for future retirees. When asked to think about the long-term future of Social Security, only 25% say some reductions in benefits for future retirees will need to be made, while 74% say benefits should not be reduced in any way.

Views on this differ somewhat by age, with younger adults more likely to say that some cuts in future benefits will be necessary. Among those ages 18 to 29, about a third (35%) hold this view compared with 27% of those ages 30 to 49 and 20% of those ages 50 and older. Views also differ by educational attainment: While roughly a third of those with a bachelor’s degree or more education (36%) say benefits will have to be reduced for future retirees, only about one-in-five (21%) of those with less education agree.

Democrats and Republicans differ modestly on the need to cut Social Security benefits. Republicans are more likely than Democrats to say reductions in future benefits are inevitable (31% vs. 22%). Still, majorities across nearly all demographic and political groups say Social Security benefits should not be reduced in any way.

Most say Americans will work into their 70s in the future in order to have the resources to retire

Thinking more broadly about what the future will look like for older adults, most Americans say adults ages 65 and older will be less prepared financially for retirement 30 years from now than today’s older adults are. Fully 72% express this view, while only 27% say older adults will be better prepared for retirement in the future.

Blacks and Hispanics are somewhat more optimistic about this than whites, and those without a bachelor’s degree are somewhat more upbeat than those with more education. Even so, the predominant view across all major demographic groups is that adults ages 65 and older will be less prepared for retirement 30 years from now compared with those who are that age today.

Consistent with these concerns, a large majority of adults think that, in 30 years, most Americans will work into their 70s in order to have enough resources to retire. About a third of adults (34%) say this will definitely happen, and an additional 50% say this will probably happen. Relatively few think adults will probably not have to work longer to retire (13%), while 3% say they definitely won’t.

Most demographic groups generally agree that people in the future will have to work longer to be financially secure enough to retire. Young adults ages 18 to 29 are somewhat less likely than their older counterparts to say this will definitely happen (25% vs. 36% of those ages 30 and older), but large majorities across all age groups say it is at least probable.

Most say cost of long-term care for older adults will fall to families, individuals

With a growing number of older adults and increased life expectancy, questions about who will care for those who can’t care for themselves and who will bear the cost of that care loom large. There’s a disconnect between who the public thinks should be responsible for paying for the care of older adults may need and who the public thinks will end up being responsible.

A narrow majority of Americans (55%) say that, 30 years from now, government should be mostly responsible for paying for the long-term care older adults may need. About three-in-ten (28%) say older adults themselves should be responsible for bearing these costs; 14% say family members should be responsible.

But, when asked who will likely be most responsible in the future for paying for this care, a majority of Americans say the burden will mainly fall on older adults themselves (36%) or their families (35%). A somewhat smaller share (28%) say government will be mostly responsible for paying for the long-term care older adults may need in the future.

Key demographic groups differ about who should pay for long-term care, but there is more agreement over who will be responsible.

Two-thirds of blacks and Hispanics say government should be mostly responsible for paying for long-term care, while about half of whites (51%) say the same. Adults ages 50 to 64 – those approaching retirement age – are more likely than other age groups to say government should be mostly responsible for this (66% of 50- to 64-year-olds say this compared with about half of all other age groups, including those 65 and older).

Lower-income adults are also more likely to say government should have the primary responsibility for this – 66% among those with annual family incomes below $30,000 hold this view, compared with about half of those with higher incomes.

Not surprisingly, Republicans and Democrats have different views about who should pay for long-term care. Republicans are evenly divided over whether government (40%) or older adults themselves (40%) should be mostly responsible for paying for the long-term care older adults may need. An additional 18% of Republicans say family members should be responsible for this. Democrats see a much bigger role for government than for individuals or families. Two-thirds of Democrats say government should be primarily responsible for this, while 21% say the responsibility should fall to individuals themselves, and 11% point to family members.

When it comes to who will be most responsible for shouldering the cost of long-term care for older adults in the future, Democrats and Republicans do not differ significantly in their views. Whites (41%) are more likely than blacks (27%) and Hispanics (20%) to say older adults themselves will be the ones to pay for this care. Higher-income adults (43% among those in families with incomes of $75,000 or more) are more likely than those with lower incomes (33%) to say the same.

The Future of Work in the Automated Workplace

The American workplace is changing rapidly, as technology and automation transform the nature of work. Even with the economy at or near full employment, the public is skeptical that the future will bring more job security, and they are wary about the long-term impact of technological innovation on workers.

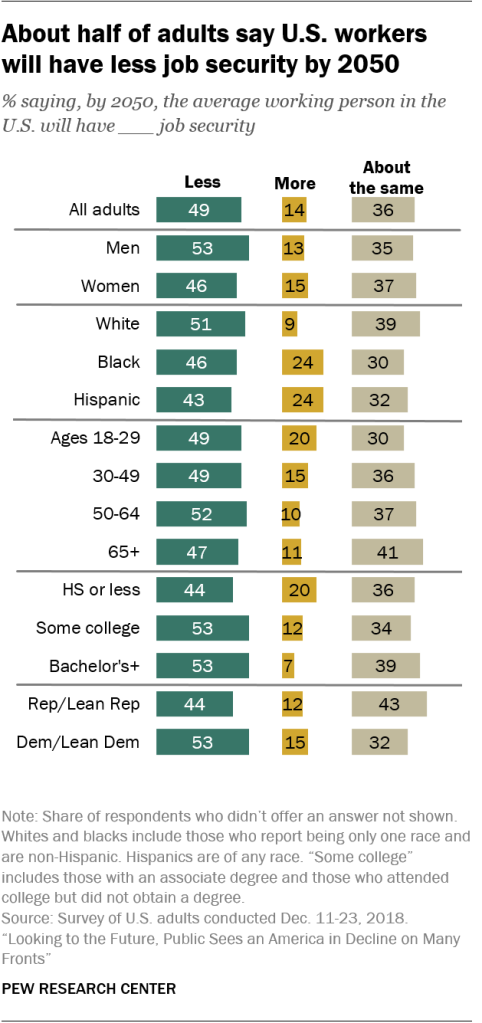

Only 14% of adults say, by the year 2050, the average working person in the U.S. will have more job security. About half (49%) say workers will have less job security, and 36% say jobs will be about as secure as they are now. Men are somewhat more pessimistic than women about future job security, and those who attended or graduated from college have a more negative outlook than those who did not continue their education beyond high school. In addition, Democrats are more likely than Republicans to predict that workers will have less job security in the future.

While pluralities across racial and ethnic groups anticipate less job security in the future, blacks and Hispanics are about twice as likely as whites to say workers will have more job security (24% of blacks and Hispanics say this compared with 9% of whites).

When asked more specifically about employee benefits in the future, public views again skew negative. Roughly one-in-five adults (22%) say, by 2050, the average working person in the U.S. will have better employee benefits than they do now. About twice that share (41%) say benefits will be worse than they are now, and 36% say they will be about the same.

Views on benefits follow similar patterns to those on job security. Men are more pessimistic than women and Democrats more downbeat than Republicans. And, again, blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to say things will be better in the future.

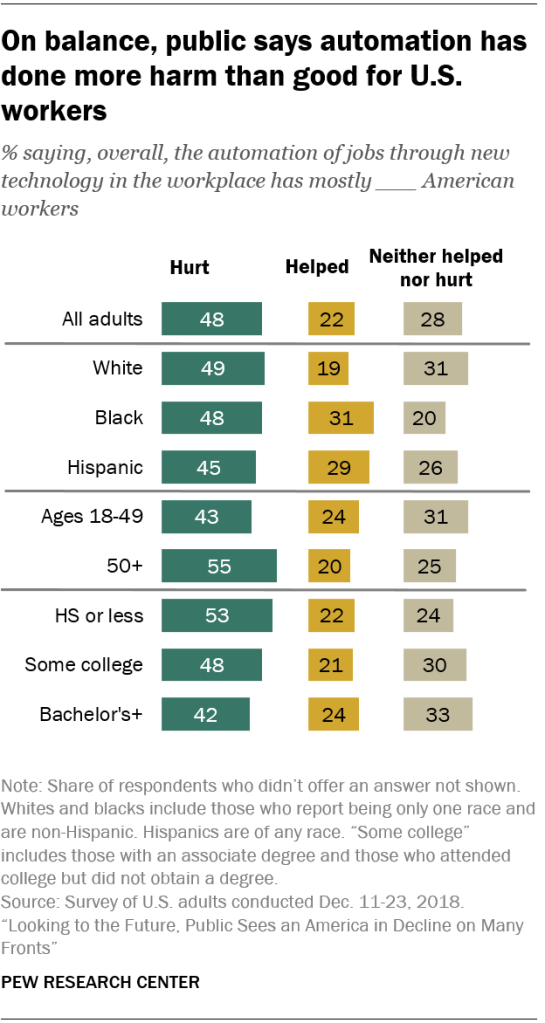

Public doesn’t see much value in automation for workers or society

Relatively few adults see an upside for workers from automation and new workplace technologies. Roughly half (48%) say these advances have mostly hurt American workers, while only 22% say they have generally helped. About three-in-ten (28%) say automation through new technology has neither helped nor hurt.

There is a notable age gap in opinions on these changes in the workplace. Adults 50 and older are more likely than their younger counterparts to say that automation has mostly hurt workers (55% vs. 43%, respectively). In addition, those with a high school degree or less education are more likely than those who attended college to see negative repercussions from new workplace technologies, while blacks and Hispanics are more likely than whites to say these changes have helped workers.

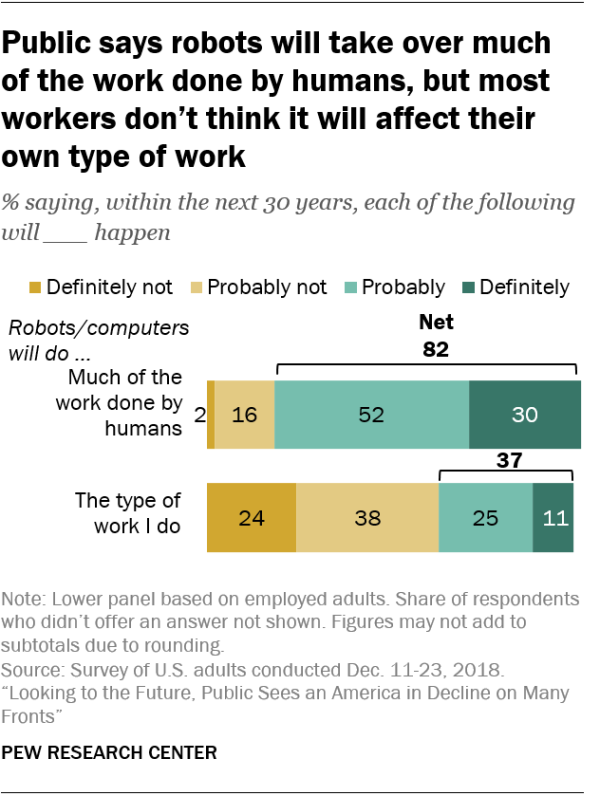

Looking forward, most Americans think automation will reshape the workplace – but not necessarily for the better. A large majority say, 30 years from now, robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans, with 30% saying this will definitely happen and 52% saying it will probably happen.

Among those who say robots and computers will do much of the work currently done by humans in the future, most think this will be a bad thing for the country – 40% say this will be somewhat bad thing and 29% say it will be a very bad thing.

In spite of these negative predictions, most workers do not believe that the type of work theycurrently do will be done by robots or computers in the future: 24% say this will definitely not happen, and 38% say it probably won’t. Still, a quarter of workers say this probably will happen, and 11% say it definitely will.

Workers with no college experience are among those most likely to say the kind of work they do will be done by robots or computers in the next 30 years: 47% of those with a high school diploma or less education say this will happen compared with 38% of those with some college experience and 27% of those with a bachelor’s or higher degree.

Lower-income workers also are more likely to say their current work will be done by robots or computers: 52% of those with an annual family income of less than $30,000 say this will happen in the future, compared with 37% of those with family incomes between $30,000 and $74,999 and 26% among those with incomes of $75,000 or higher.

Americans have a negative view of the broader impact that automation will have on society. Roughly three-quarters of adults (76%) say inequality between the rich and the poor will increase if robots and computers perform most of the jobs currently being done by humans.

This sentiment is widely held across most demographic groups. Democrats (82%) are somewhat more likely than Republicans to say that inequality will increase. But, even among Republicans, 72% say this change is likely.

The public is also skeptical that more good jobs will be created if robots and computers play a bigger role in the workplace. About two-thirds of adults (66%) doubt that the economy will generate many new, better paying jobs if robots and computers mostly replace human labor, twice the share that say better jobs will follow widespread implementation of these technologies.

Higher-income adults and those with a bachelor’s degree or more education are somewhat more optimistic that new technology will create better jobs. But, even among these groups, majorities say greater automation in the workplace isn’t likely to lead to an improved job picture in 30 years.

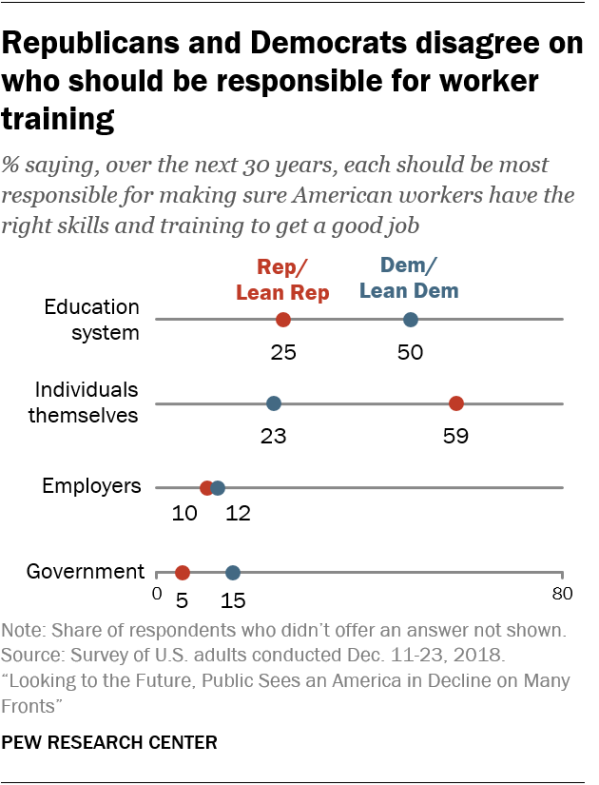

Few say government or employers are primarily responsible for providing workers with skills and training

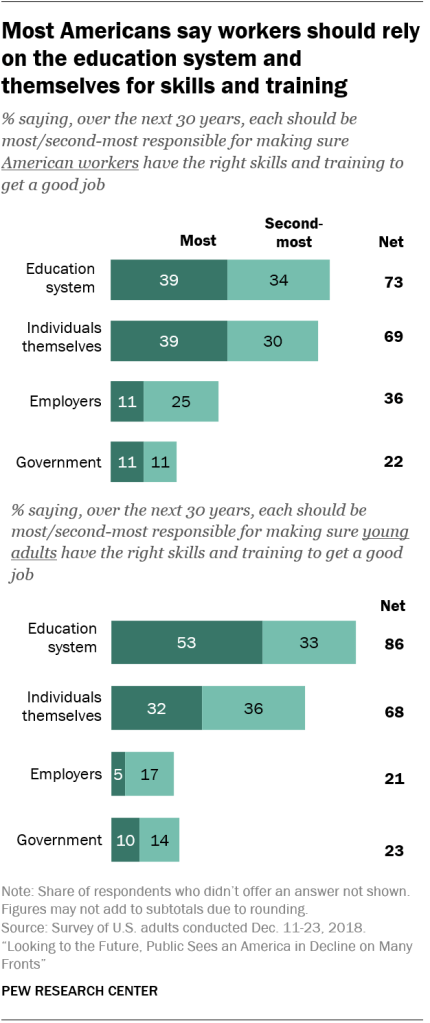

Previous research has shown that the vast majority of American workers believe it will be important – if not essential – for them to get training and develop new skills throughout their work life in order to keep up with changes in the workplace. Most adults say the primary responsibility for providing workers with the necessary skills and training resides with the education system and individuals themselves rather than with government or employers.

When asked who should be most responsible, over the next 30 years, for making sure American workers have the right skills and training to get a good job, about four-in-ten adults (39%) point to the education system. An additional 34% say the education system should be second-most responsible. Similar shares say individuals themselves bear the primary (39%) or secondary (30%) responsibility for ensuring that workers have the necessary training to get a good job.

By comparison, the public is much less likely to say employers or government should play this role. Only 11% of adults say employers should be most responsible for ensuring workers have the right skills and training, and the same share say government should be most responsible. Some 25% and 11%, respectively, say employers and government should have secondary responsibility in this area.

The public sees education playing an even bigger role when it comes to ensuring young adults have the skills and training they need to get a good job. Roughly half (53%) say the education system should be most responsible for providing young people with the necessary tools to succeed in the labor force, while 32% say it should be up to young adults themselves. Overall, more than eight-in-ten adults look to the education system to play a primary or secondary role in preparing young people for the workforce. About seven-in-ten say the onus should be on individuals themselves.