Racial profiling constituted a fact of life for African Americans as long as there have been organized police forces in the U.S.

By David A. Harris, J.D.

Sally Ann Semenko Endowed Chair

Professor of Law

University of Pittsburgh Law School

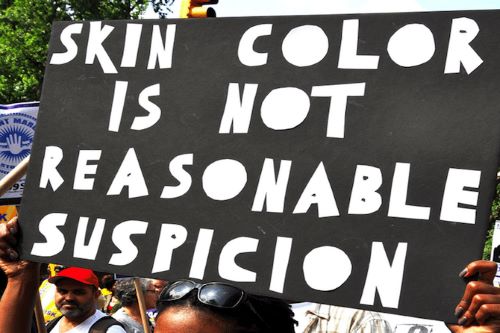

Looking back from the distance of two decades, we know that this did not happen. Racial profiling did not end with the Bush administration; in fact, it intensified, even while it changed shape and took on new targets. But the tactic remained the same: using racial or ethnic appearance as an indicator of suspicion, followed by law enforcement engagement.

It is important to acknowledge that many American police departments have made efforts to address racial profiling. They have recognized the reality of the practice and used their own internal rules, regulations, and policies to prohibit it. They have also incorporated those policies into training. Some smaller number of departments have also committed to collecting data on all traffic stops, stops and frisks, and other routine police practices. But the unfortunate reality is that racial profiling remains with us.

Where does this practice stand now? What evidence exists on how it works to achieve crime-fighting and public safety goals? And what effects does the practice have in the communities supposedly served by aggressive forms of policing? We do not lack ways to confront and root out this tactic and the damage it does; what we need now—what we have always needed—remains the political will to challenge and change what law enforcement does on a basic level. We knew in 2000, and we know now, that racial profiling does not make us safer. In fact, it may make us less safe, as it misses its intended targets, blinds law enforcement, and serves as salt in the wounds that keep police departments and communities of color at odds and apart from each other.

A Definition, and a Little History

Understanding racial profiling requires a good working definition. Though some prefer other names for the tactic—for example, biased policing or bias-based policing—racial profiling remains the most common term. For purposes of this discussion, I define racial profiling as the law enforcement practice of using race, ethnicity, national origin, or religious appearance as one factor, among others, when police decide which people are suspicious enough to warrant police stops, questioning, frisks, searches, and other routine police practices. Notice that this definition does not require that racial or ethnic appearance acts as the sole factor motivating what an officer does; such a narrow conception would define racial profiling out of existence because few if any law enforcement encounters occur based on a single factor. Note also that using a reasonably detailed description that includes the race of a suspect who has been observed is not racial profiling. If a witness describes the person seen running from the convenience store that just experienced a robbery as male, black, five foot ten inches tall, 20 to 24 years old, wearing a green sweatshirt and black Nike sneakers, and having a mustache and a goatee, a police bulletin using this description does not constitute racial profiling. Rather, it constitutes good police work. Race, in the context of a reasonably detailed description, is a better descriptor than any clothing worn or facial hair; a suspect can change both of those with ease. Racial appearance, in contrast, does not change, and sticks in the mind.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT THE AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION