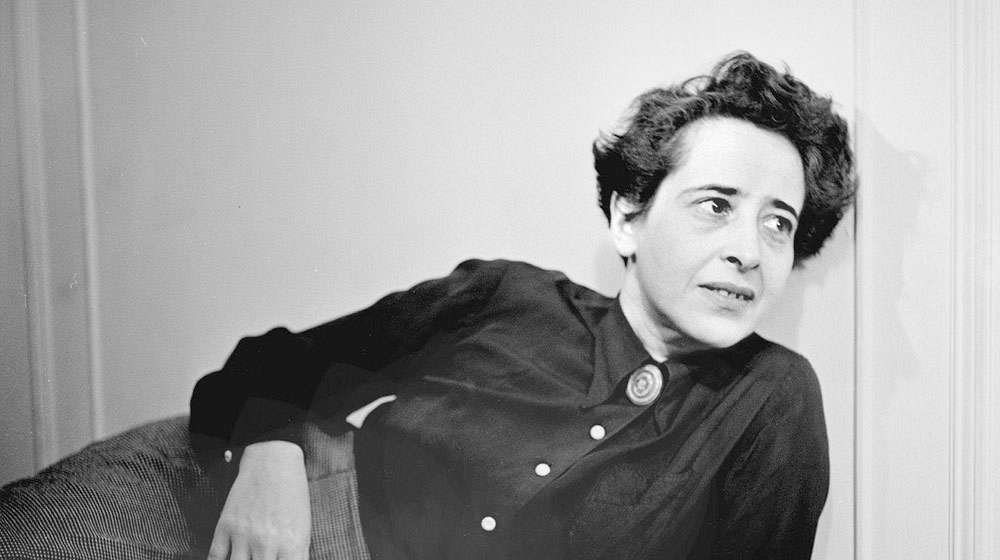

Hannah Arendt in 1944. Portrait by photographer Fred Stein (1909-1967) who emigrated 1933 from Nazi Germany to France and finally to the USA. Fred Stein/Press Association.

Arendt’s fundamental insight was that humans are not born equal; rather, a political construction is needed to create equality of public voice.

By Dr. Ashoka Mody / 07.31.2018

Charles and Marie Robertson Visiting Assistant Professor in International Economic Policy

Princeton University

In 1933, Hannah Arendt, a 27-year-old German Jew, was held by Nazi interrogators. Mysteriously, she was among the few who were released. She left Germany illegally and found her way to Paris. In 1940, as German troops appeared set to occupy France, French authorities placed Arendt and other Germans in internment camps as “enemy aliens.” Arendt escaped that internment. She needed another miracle, which appeared in the form of a chance friendship, through which she obtained a visa for the United States. She then managed to secure passage through Portugal, arriving in New York in 1941.

Arendt’s experience as a Jew in Nazi Germany and her status in the United States as a refugee shaped her political philosophy. As she wrote, “Thought itself arises out of the actuality of incidents, and incidents of living experience must remain its guideposts.” She explained: “incidents and stories behind them contain in a nutshell the full meaning of whatever we have to say.”

Hannah Arendt chose from the incidents and stories in her life to write, among other things, about the Jewish state, the rights of refugees, and the fragility of democracy. She died in 1975. But as the political philosopher Richard Bernstein reminds us in his elegant new book, Why Read Hannah Arendt Now, by Richard Bernstein, (Polity Press), Arendt gives us humane guideposts through some of today’s most difficult political dilemmas. Bernstein, an 86-year-old professor at the New School of Social Research in New York, has been drawn repeatedly to political activism. Few are better placed to explain why we must read Hannah Arendt today.

Arendt championed the cause of the “Jewish pariah.” “The emancipated Jew,” she wrote, “must awake to an awareness of his position. … His fight for freedom is part and parcel of that which all the downtrodden of Europe must wage to achieve national and social liberation.” For this reason, she was alarmed by Zionists who in 1942 visualized a Jewish state that would give minority rights to Arabs even though they formed a majority of the population. She was alarmed by the emerging historical narrative of the superiority of “victorious” causes. She appealed for dialogue. “To hold different opinions and to be aware that other people think differently on the same issue shields us from Godlike certainty which stops all discussion and reduces social relationships to an ant heap.”

Arendt’s own solution appears politically quaint today but reflects her broader philosophy of productive coexistence in a democracy. Rather than two states, she called for a federated state of Jews and Arabs, within which Jewish-Arab councils would manage local communities. The alternative, she warned, was that “The ‘victorious’ Jews would live surrounded by an entirely hostile Arab population, secluded inside ever-threatened borders, absorbed with physical self-defense to a degree that would submerge all other interests and activities.”

Refugees

Even as she was reflecting on a future Jewish state, Arendt was dealing with her own status as a refugee. In her escape to America, she had received help from refugee organizations at crucial moments. Many of her friends were refugees. Thus, Bernstein comments, Arendt “wrote about refugees with insight, wit, irony, and a deep sense of melancholy.” Soon after her arrival in the United States, she wrote the essay “We Refugees.” Its opening sentence carries a disturbing echo into the present: “In the first place, we don’t like to be called ‘refugees.’ We ourselves call each other ‘newcomers’ or ‘immigrants.’”

Today, the concept of “newcomer” does not exist and the entire debate about migration pivots on a stark distinction between “refugee” and “immigrant.” Refugees are, in principle, welcome as long as they are not really economic migrants. Under the UN Refugee Convention, signatory countries accept an obligation to admit those who have a well-founded fear of persecution and, therefore, qualify for asylum. Where once, asylum seekers were routinely granted entry as refugees, today such applicants are increasingly often rejected as economic migrants. This distinction between refugees and migrants has become steadily sharper since around the time of Arendt’s death. Didier Fassin, the anthropologist and sociologist, writes that in his native France, refugees from Chile and Vietnam were welcomed up until the 1970s. But as the postwar economic momentum faded, there was less need for foreign workers to boost the domestic labor force. The potential numbers of refugees and migrants swelled, and the sense that they were an economic and cultural threat grew.

Fassin adds that the moral obligation to refugees has also eroded. All lives do not have the same price, he says. In France, the notorious Calais “Jungle,” housed, at its peak, nearly 10,000 asylum seekers and migrants living in inhumane conditions. Although the Jungle was dismantled in 2016, several hundred, hoping to smuggle themselves onto trains or trucks crossing the channel, have reassembled there and live without proper access to emergency shelter, water, and sanitation. Even more so than in France, asylum seekers who risk their lives to reach Greece and Italy end up in camps plagued by violence, human trafficking, and the criminalization of aid workers.

The world faces a hard problem. The sheer numbers of asylum seekers is large and increasing, and most of them are desperately poor. Such potential refugees buy, in effect, lottery tickets from well-organized smugglers, with the downside risk that they could lose their lives. Moreover, the asylum seekers and migrants are coming from far-flung countries such as Mali, Bangladesh, and Guatemala, places very different from the countries of reception, making integration costly.

Meanwhile, what evidence there is strongly suggests that harsh policies by host country authorities do discourage illegal flows—although they discourage legitimate economic migration as well. Bernstein is therefore right that the refugee question, about which Arendt worried greatly, has strong echoes today. Her principle was that everyone has the “right to have rights.” Unfortunately, with the vast income and cultural differences across which human beings are moving today, this is one of those issues where giving rights to refugees and migrants in advanced nations will not solve the problem. Oxford University’s Paul Collier has passionately called for improving the lot of refugees not only in their home countries but also in the many neighboring countries to which they flee. Arendt surely would have reinforced this call.

Dialogue

A final theme that I take up here is Arendt’s passionate advocacy of public spaces for dialogue. In this, her views were shaped by her narrow escape from totalitarianism. For that reason, perhaps, she was deeply concerned about the fragility of democracy.

In one of her most famous essays, “Truth and Politics,” she opened with a dramatic statement: “Truth and politics are on rather bad terms with each other, and no one, as far as I know, has ever counted truthfulness among the political virtues.” She emphasized that not just the demagogue but even the statesman regards lies as “justifiable tools” of the trade. As a result, “The chances of factual truth surviving the onslaught of power are very slim indeed; not only for a time but, potentially, forever.” She asked, poignantly and rhetorically, “What kind of reality does truth possess if it is powerless in the public realm?”

For Arendt, the antagonism between truth and politics always lies latent in public discourse. If facts “oppose a given group’s profit or pleasure,” it is all too easy to disdain the facts or regard them with “hostility.” Even well-established facts can be dismissed as merely “opinions.” Skilled politicians can exploit “rhetorical” devices to promote their favored opinion and thus garner ever-larger numbers of supporters. “Mass manipulation of fact and opinion” then lead to “rewriting of history” and “image-making,” a phenomenon that the cognitive linguist George Lakoff would call “framing.” In psychologist Irving Janis’s terminology, discourse and decision-making fall under the spell of “groupthink.”

This antagonism between truth and politics, Arendt warned, can degenerate into tyranny. Truth, she explained, is “hated by tyrants.” To oppose the “infuriating stubbornness” – indeed, the “coercive power” – of truth, authoritarian rulers hold on to their power by propagating “plain lies.”

The echoes into the present are all too evident. Lies are justified as plausible opinions, “alternative facts,” by authoritarian populists and by their followers who are in search of saviors to better their lot. Donald Trump’s ascent to the American presidency and his hold on a core group of supporters fits the pattern exactly. In India, Prime Minister Narendra Modi has placed Mahatma Gandhi on a pedestal while his supporters engage in wanton violence against Muslims and other minorities. Modi’s surrogates continue to portray his demonetization initiative – which outlawed bank notes worth 500 rupees or more – as a great success, while all evidence points to severe human and economic distress with little gain in rooting out ill-gotten wealth held in cash.

Because her analysis led her to this inherent conflict between truth and politics, Arendt was deeply suspicious of large nation-states, in which, she feared, authoritarian leaders could manipulate facts to sway large numbers of people. Seeking to “recover the dignity of politics,” Bernstein writes, Arendt was guided by the same vision that led her to advocate “local Arab-Jewish councils organized in a federated state.”

She believed that such dignity had been achieved at “privileged moments” in history, such as during the American and French revolutions, and also during the Budapest uprising in 1956. The Indian freedom movement would have fitted that pattern. Arendt was drawn to such movements because, as Bernstein explains, they fostered “debate, deliberation, contesting, and sharing of opinions.”

Bernstein adds that such fruitful moments are not easy to sustain. Indeed, Thomas Jefferson, one of the authors of the American constitution that Arendt so admired as embodying the spirit of the American Revolution, worried that a constructive “revolutionary spirit” could easily fade. False saviors can also hijack legitimate causes. Nevertheless, with the overwhelming power of nation-states, Arendt’s message of the importance of direct democracy as a counterweight to aloof and self-interest-ridden representative democracy surely deserves close attention.

Arendt’s fundamental insight was that humans are not born equal; rather, a political construction is needed to create equality of public voice. Hence, as Bernstein elaborates, she was led to the notion of “public spaces where individuals can act, deliberate, and be judged by their actions and opinions.” Only then can a political system be based on “rational persuasion” rather than on coercion and violence. The role of “rational persuasion” becomes all the more important when we recognize, as the political theorist Robert Dahl emphasized in his magisterial Preface to Democratic Theory, that often a policy question does not have a “right” technical answer.

European Union

Arendt died in 1975 and so did not witness the steady expansion of the European Union. She would, I believe, have been dismayed, as economic historian Alan Milward was, by the fact that democracy in Europe was “falling through the interstices of the nation-state and the supranation.” With her emphasis on local councils and public spaces, Arendt cautioned against the extension of the “representative state,” where decision makers are further and further removed from the voice of the people. Such distant decision-making accounts, in part, for a phenomenon described by the author Pankaj Mishra: “a severely diminished respect for the political process itself.” The European Union carries the concept of representative state to its extreme, causing extraordinary fuzziness in accountability and responsibility, and hence necessarily breeds citizens’ frustration and anger.

Joachim Gauck, former German president and winner of the Hannah Arendt Prize for Political Thought, was one of those rare European insiders who have bemoaned the loss of democracy in Europe. In a speech in February 2013, with the prolonged eurozone crisis still taking its toll, Gauck said, “In some member states, people are afraid they are the ones footing the bill in this crisis. In others, there is growing fear of facing ever harsher austerity and falling into poverty. For many ordinary people in Europe, the balance between giving and receiving, between debt and liability, responsibility and a place at the table no longer seems fair.” Gauck said pointedly, “the European Union leaves too many people feeling powerless and without a voice.” And he added, “it is still hard to pinpoint what it is that makes us European, what it means to have a European identity.”

Gauck’s speech tried to puncture the image of a Europe with a clear identity and sense of purpose. But few paid attention to his message. The image remains intact. The language evolves but the underlying rhetoric remains unchanged: “an ever-closer union,” “unity in diversity,” or in French president Emmanuel Macron’s latest formulation, “European sovereignty.” Such words acquire a coercive cynicism because they lack any operational content while corrosive differences fester among member states.

Gauck appealed for a common language of human dignity and values rather than technical and administrative centralization to unify Europeans. Such a common language, he said, in Hannah Arendt’s spirit, would need to be fostered in “a European agora, a common forum for discussion to enable us to live together in a democratic order.” Like Arendt’s conception of Arab-Jew councils, Gauck’s vision of a modern agora remains politically quaint. But his prognosis, as was Arendt’s on the future of the Jewish state, remains a warning.

Bernstein ends his beautiful little book by reminding the reader that Hannah Arendt “rejected both reckless optimism and reckless despair.” Arendt’s optimism, Bernstein says, lay in her belief that human beings had “the capacity to act in concert, to initiate, to strive, to make freedom a worldly reality.” But to achieve that freedom, she wrote, it was necessary to begin the urgent task before it “becomes a historical event.”

Originally published by openDemocracy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International licence.