How many colors in your language’s rainbow? / Shutterstock

By Dr. Claire Bowern / 11.16.2016

Associate Professor of Linguistics

Yale University

It is striking that English color words come from many sources. Some of the more exotic ones, like “vermilion” and “chartreuse,” were borrowed from French, and are named after the color of a particular item (a type of mercury and a liquor, respectively). But even our words “black” and “white” didn’t originate as color terms. “Black” comes from a word meaning “burnt,” and “white” comes from a word meaning “shining.”

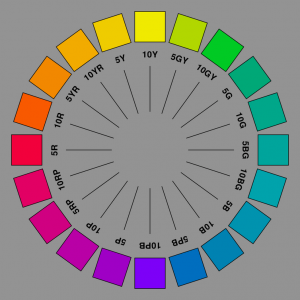

Color words vary a lot across the world. Most languages have between two and 11 basic color words. English, for example, has the full set of eight basic colors: black, white, red, green, yellow, blue, pink, gray, brown, orange and purple. In a 1999 survey by linguists Paul Kay and Luisa Maffi, languages were roughly equally distributed between the basic color categories that they tracked.

In languages with fewer terms than this – such as the Alaskan language Yup’ik with its five terms – the range of a word expands. For example, for languages without a separate word for “orange,” hues that we’d call “orange” in English might be named by the same color that English speakers would call “red” or “yellow.” We can think of these terms as a system that together cover the visible spectrum, but where individual terms are centered on various parts of that spectrum.

Illustration of a color system with 20 hues. Thenoizz

Does that mean that speakers of languages with fewer words for colors see less color? No, just as English speakers can see the difference between the “blue” of the sky and the “blue” of an M&M. Moreover, if language words limited our perception of color, words wouldn’t be able to change; speakers would not be able to add new distinctions.

My colleague Hannah Haynie and I were interested in how color terms might change over time, and in particular, in how color terms might change as a system. That is, do the words change independently, or does change in one word trigger a change in others? In our research, recently published in the journal PNAS, we used a computer modeling technique more common in biology than linguistics to investigate typical patterns and rates of color term change. Contrary to previous assumptions, what we found suggests that color words aren’t unique in how they evolve in language.

Questioning common conceptions on colors

Previous work (such as by anthropological linguists Brent Berlin and Paul Kay) has suggested that the order in which new color terms are added to a language is largely fixed. Speakers begin with two terms – one covering “black” and dark hues, the other covering “white” and light hues. There are plenty of languages with only two color terms, but in all cases, one of the color terms is centered on “black” and the other on “white.”

When a language has three terms, the third is one is almost always centered on hues that English speakers would call “red.” There are no languages with three color terms where the named colors are centered on black, white and light green, for example. If a language has four color terms, they will be black, white, red and either yellow or green. In the next stage, both yellow and green are present, while the next color terms to be added are blue and brown (in that order). Cognitive scientists and linguists such as Terry Regier have argued that these particular parts of the color spectrum are most noticeable for people.

Berlin and Kay also hypothesized that language speakers don’t lose color terms. For example, once a language has a distinction between “red-like” hues (such as blood) and “yellow-like” ones (such as bananas), they wouldn’t collapse the distinction and go back to calling them all by the same color name again.

This would make color words quite different from other areas of language change, where words come and go. For example, words can change their meaning when they are used metaphorically, but over time the metaphoric meaning becomes basic. They can broaden or narrow their meanings; for example, English “starve” used to mean “die” (generally), not “die of hunger,” as it primarily means now. “Starve” has also acquired metaphorical meanings.

That there’s something unique about the stability of color concepts is an assumption we wanted to investigate. We were also interested in patterns of color naming and where color terms come from. And we wanted to look at the rates of change – that is, if color terms are added, do speakers tend to add lots of them? Or are the additions more independent, with color terms added one at a time?

Everyone sees them all, but languages divide them into different color terms. / Shutterstock

Modeling how a language tree grew

We tested these ideas using color words in Australian Aboriginal languages. We worked with Australian languages (rather than European or other languages) for several reasons. Color demarcations vary in Indo-European, but the number of colors in each language is pretty similar; the ranges differ but the number of colors don’t vary very much. Russian has two terms that cover the hues that English speakers call “blue,” but Indo-European languages have many terms.

In contrast, Australian languages are a lot more variable, ranging from systems like Darkinyung’s, with just two terms (mining for “black” and barag for “white”), to languages like Kaytetye, where there are at least eight colors, or Bidyara with six. That variation gave us more points of data. Also, there are simply a lot of languages in Australia: Of the more than 400 spoken at the time of European settlement, we had color data for 189 languages of the Pama-Nyungan family, from the Chirila database of Australian languages.

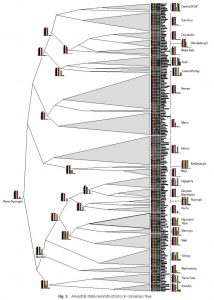

In order to answer these questions, we used techniques originally developed in biology. Phylogenetic methods use computers to study the remote past. In brief, we use probability theory, combined with a family tree of languages, to make a model of what the history of the color words might have been.

First, we construct a tree that shows how languages are related to one another. The contemporary Pama-Nyungan languages are all descended from a single ancestor language. Over 6,000 years, Proto-Pama-Nyungan split into different dialects, and those dialects turned into different languages: about 300 of them at the time of the European settlement of Australia. Linguists usually show those splits on a family tree diagram.

Family tree of Australian languages with their color terms and reconstructions of color systems for major subgroups. Haynie and Bowern (2016): Figure 3

Then, we build a model for that tree of how different features (in this case, color terms) are gained or lost, and how quickly those features might change. This is a complicated problem; we estimate likely reconstructions, evaluate that model for how well it fits our hypotheses, tweak the model parameters a bit to produce a different set of results, score that model, and so on. We repeat this many times (millions of times, usually) and then take a random sample of our estimates. This method is due originally to evolutionary biologists Mark Pagel and Andrew Meade.

Estimates that are very consistent (like reconstructing terms for “black,” “white” and “red”) are highly likely to be good reconstructions. Other forms were consistently reconstructed as absent (for instance, “blue” from many parts of the tree). A third set of forms were more variable, such as “yellow” and “green” in some parts of the tree; in that case, we have some evidence they were present, but it’s unclear.

Our results supported some of the previous findings, but questioned others. In general, our findings backed up Berlin and Kay’s ideas about the sequential adding of terms, in the order they proposed. For the most part, our color data showed that Australian languages also show the patterns of color term naming that have been proposed elsewhere in the world; if there are three named colors, they will be black, white and red (not, for example, black, white and purple). But we show that it is most likely that Australian languages have lost color terms, as well as gained them. This contradicts 40 years of assumptions of how color terms change – and makes color words look a lot more like other words.

We also looked at where the color words themselves came from. Some were old in the family, and seemed to go back as color terms. Others relate to the environment (like tyimpa for “black” in Yandruwandha, which is related to a word which means “ashes” in other languages) or to other color words (compare Yolŋu miku for “red,” which also sometimes means simply “colored”). So Australian languages show similar sources of color terms to languages elsewhere in the world: color words change when people draw analogies with items in their environment.

Our research shows the potential for using language change to study areas of science that have previously been more closely examined by fields such as psychology. Psychologists and psycholinguists have described how constraints from our vision systems lead to particular areas of the color spectrum being named. We show that these constraints apply to color loss as well as gain. Just as it’s a lot easier to see a chameleon when it moves, language change makes it possible to see how words are working.