Geographical consultations with shamans showed the relationship between imperialism, exploration, and indigenous environmental knowledge.

By Dr. Shane McCorristine

Lecturer in Modern British History

Newcastle University

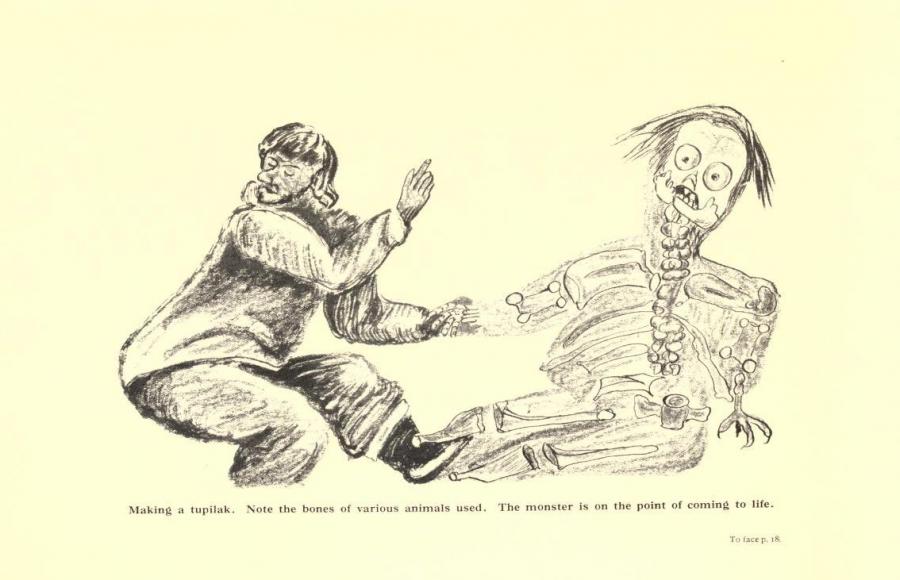

By and large, British Arctic explorers lacked local knowledge of the environments through which they passed and, consequently, sometimes consulted Inuit shamans, whose geographical knowledge was known to be extensive. That these consultations could be made either in the formal atmosphere of the ship with maps and charts or during a shamanic séance in an indigenous hut is significant. Throughout the nineteenth century explorers derided shamanism as a superstition, yet at the same time remained fascinated by the shamanic séance.

For example, during an 1821–23 expedition to seek the Northwest Passage, Lieutenant William H. Hooper described how he asked an Iglulingmiut shaman, Toolemak, to perform “some of the ceremonies of Angetkokism.” Despite Hooper’s scepticism of Toolemak’s “conjurations,” he wanted the shaman to find out if the expedition’s ships could achieve a Northwest Passage. Following some chanting, Toolemak contacted his helping spirit [tuurngaq] (calling upon the British officers “to become his auxiliaries” in the process), who answered that their ships would not be able to reach their destination due to the quantity of ice and would then “return to Kabloona-noona” [white man’s land].

This expedition, commanded by William Edward Parry, was indeed repelled by the ice at Fury and Hecla Strait and then departed the Canadian Arctic. Incidents such as this serve to remind us that Inuit and British cosmologies frequently overlapped, and for both communities the point of these séances was not just to display supernatural powers but to fulfill requests for environmental information. Geographical consultations with shamans, and the increasing appearance of British officers in these visions points to a more complex image of the relationship between imperialism, exploration, and indigenous environmental knowledge. Furthermore this relationship can be linked to broader ambivalent attitudes and cultures of curiosity in western encounters with “the supernatural.”

Originally published by Arcadia: Explorations in Environmental History, 1 (2012), under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.