Reconstruction’s influence of and effects upon religion, education, industry, and taxation.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Organized Religion

Freedmen were very active in forming their own churches, mostly Baptist or Methodist, and giving their ministers both moral and political leadership roles. In a process of self-segregation, practically all blacks left white churches so that few racially integrated congregations remained (apart from some Catholic churches in Louisiana). They started many new black Baptist churches and soon, new black state associations.

Four main groups competed with each other across the South to form new Methodist churches composed of freedmen. They were the African Methodist Episcopal Church; the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, both independent black denominations founded in Philadelphia and New York, respectively; the Colored Methodist Episcopal Church (which was sponsored by the white Methodist Episcopal Church, South) and the well-funded Methodist Episcopal Church (Northern white Methodists). The Methodist Church had split before the war due to disagreements about slavery.[1][2] By 1871 the Northern Methodists had 88,000 black members in the South, and had opened numerous schools for them.[3]

Blacks in the South made up a core element of the Republican Party. Their ministers had powerful political roles that were distinctive since they did not depend on white support, in contrast to teachers, politicians, businessmen, and tenant farmers.[4] Acting on the principle as stated by Charles H. Pearce, an AME minister in Florida: “A man in this State cannot do his whole duty as a minister except he looks out for the political interests of his people,” more than 100 black ministers were elected to state legislatures during Reconstruction, as well as several to Congress and one, Hiram Revels, to the U.S. Senate.[5]

In a highly controversial action during the war, the Northern Methodists used the Army to seize control of Methodist churches in large cities, over the vehement protests of the Southern Methodists. Historian Ralph Morrow reports:

A War Department order of November, 1863, applicable to the Southwestern states of the Confederacy, authorized the Northern Methodists to occupy “all houses of worship belonging to the Methodist Episcopal Church South in which a loyal minister, appointed by a loyal bishop of said church, does not officiate”.[6][7][8]

Across the North most evangelical denominations, especially the Methodists, Congregationalists and Presbyterians, as well as the Quakers, strongly supported Radical policies. The focus on social problems paved the way for the Social Gospel movement. Matthew Simpson, a Methodist bishop, played a leading role in mobilizing the Northern Methodists for the cause. His biographer calls him the “High Priest of the Radical Republicans”.[9] The Methodist Ministers Association of Boston, meeting two weeks after Lincoln’s assassination, called for a hard line against the Confederate leadership:

Resolved, That no terms should be made with traitors, no compromise with rebels … That we hold the National authority bound by the most solemn obligation to God and man to bring all the civil and military leaders of the rebellion to trial by due course of law, and when they are clearly convicted, to execute them.[10][11]

The denominations all sent missionaries, teachers and activists to the South to help the freedmen. Only the Methodists made many converts, however.[12] Activists sponsored by Northern Methodist Church played a major role in the Freedmen’s Bureau, notably in such key educational roles as the Bureau’s state superintendent or assistant superintendent of education for Virginia, Florida, Alabama, and South Carolina.[13]

Many Americans interpreted great events in religious terms. Historian Wilson Fallin contrasts the interpretation of Civil War and Reconstruction in white versus black Baptist sermons in Alabama. White Baptists expressed the view that:

God had chastised them and given them a special mission – to maintain orthodoxy, strict biblicism, personal piety, and traditional race relations. Slavery, they insisted, had not been sinful. Rather, emancipation was a historical tragedy and the end of Reconstruction was a clear sign of God’s favor.

In sharp contrast, Black Baptists interpreted the Civil War, emancipation and Reconstruction as:

God’s gift of freedom. They appreciated opportunities to exercise their independence, to worship in their own way, to affirm their worth and dignity, and to proclaim the fatherhood of God and the brotherhood of man. Most of all, they could form their own churches, associations, and conventions. These institutions offered self-help and racial uplift, and provided places where the gospel of liberation could be proclaimed. As a result, black preachers continued to insist that God would protect and help him; God would be their rock in a stormy land.[14]

Public Schools

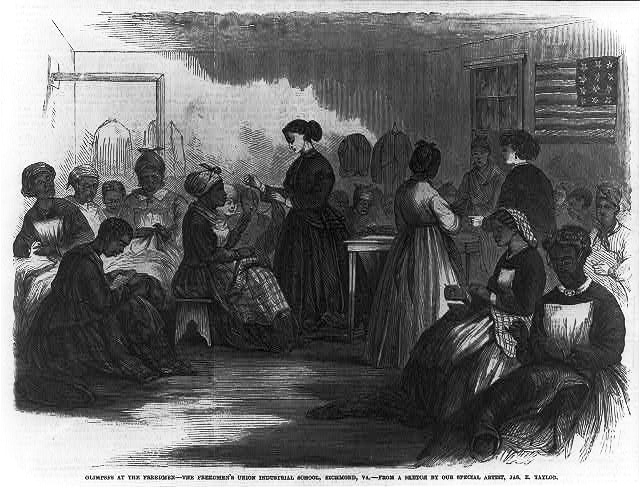

Historian James D. Anderson argues that the freed slaves were the first Southerners “to campaign for universal, state-supported public education”.[15] Blacks in the Republican coalition played a critical role in establishing the principle in state constitutions for the first time during congressional Reconstruction. Some slaves had learned to read from white playmates or colleagues before formal education was allowed by law; African Americans started “native schools” before the end of the war; Sabbath schools were another widespread means that freedmen developed to teach literacy.[16] When they gained suffrage, black politicians took this commitment to public education to state constitutional conventions.

The Republicans created a system of public schools, which were segregated by race everywhere except New Orleans. Generally, elementary and a few secondary schools were built in most cities, and occasionally in the countryside, but the South had few cities.[17][18]

The rural areas faced many difficulties opening and maintaining public schools. In the country, the public school was often a one-room affair that attracted about half the younger children. The teachers were poorly paid, and their pay was often in arrears.[19] Conservatives contended the rural schools were too expensive and unnecessary for a region where the vast majority of people were cotton or tobacco farmers. They had no vision of a better future for their residents. One historian found that the schools were less effective than they might have been because “poverty, the inability of the states to collect taxes, and inefficiency and corruption in many places prevented successful operation of the schools.”[20] After Reconstruction ended and the whites disfranchised the blacks and imposed Jim Crow, they consistently underfunded black institutions, including the schools.

After the war, northern missionaries founded numerous private academies and colleges for freedmen across the South. In addition, every state founded state colleges for freedmen, such as Alcorn State University in Mississippi. The normal schools and state colleges produced generations of teachers who were integral to the education of African-American children under the segregated system. By the end of the century, the majority of African Americans were literate.

In the late 19th century, the federal government established land grant legislation to provide funding for higher education across the United States. Learning that blacks were excluded from land grant colleges in the South, in 1890 the federal government insisted that southern states establish black state institutions as land grant colleges to provide for black higher education, in order to continue to receive funds for their already established white schools. Some states classified their black state colleges as land grant institutions. Former Congressman John Roy Lynch wrote, “there are very many liberal, fair-minded and influential Democrats in the State [Mississippi] who are strongly in favor of having the State provide for the liberal education of both races.”[21][22]

Railroad Subsidies and Payoffs

Every Southern state subsidized railroads, which modernizers believed could haul the South out of isolation and poverty. Millions of dollars in bonds and subsidies were fraudulently pocketed. One ring in North Carolina spent $200,000 in bribing the legislature and obtained millions in state money for its railroads. Instead of building new track, however, it used the funds to speculate in bonds, reward friends with extravagant fees, and enjoy lavish trips to Europe.[23] Taxes were quadrupled across the South to pay off the railroad bonds and the school costs.

There were complaints among taxpayers because taxes had historically been low, as the planter elite was not committed to public infrastructure or public education. Taxes historically had been much lower in the South than in the North, reflecting the lack of government investment by the communities.[24] Nevertheless, thousands of miles of lines were built as the Southern system expanded from 11,000 miles (17,700 km) in 1870 to 29,000 miles (46,700 km) in 1890. The lines were owned and directed overwhelmingly by Northerners. Railroads helped create a mechanically skilled group of craftsmen and broke the isolation of much of the region. Passengers were few, however, and apart from hauling the cotton crop when it was harvested, there was little freight traffic.[25] As Franklin explains, “numerous railroads fed at the public trough by bribing legislators … and through the use and misuse of state funds.” The effect, according to one businessman, “was to drive capital from the State, paralyze industry, and demoralize labor”.[26]

Taxation during Reconstruction

Reconstruction changed the means of taxation in the South. In the U.S. from the earliest days until today, a major source of state revenue was the property tax. In the South, wealthy landowners were allowed to self-assess the value of their own land. These fraudulent assessments were almost valueless, and pre-war property tax collections were lacking due to property value misrepresentation. State revenues came from fees and from sales taxes on slave auctions.[27] Some states assessed property owners by a combination of land value and a capitation tax, a tax on each worker employed. This tax was often assessed in a way to discourage a free labor market, where a slave was assessed at 75 cents, while a free white was assessed at a dollar or more, and a free African American at $3 or more. Some revenue also came from poll taxes. These taxes were more than poor people could pay, with the designed and inevitable consequence that they did not vote.

During Reconstruction, the state legislature mobilized to provide for public need more than had previous governments: establishing public schools and investing in infrastructure, as well as charitable institutions such as hospitals and asylums. The needed to increase taxes which were abnormally low. The planters had provided privately for their own needs. There was some fraudulent spending in the postwar years; a collapse in state credit because of huge deficits, forced the states to increase property tax rates. In places, the rate went up to ten times higher—despite the poverty of the region. The planters had not invested in infrastructure and much had been destroyed during the war. In part, the new tax system was designed to force owners of large plantations with huge tracts of uncultivated land either to sell or to have it confiscated for failure to pay taxes.[28] The taxes would serve as a market-based system for redistributing the land to the landless freedmen and white poor. Mississippi, for instance, was mostly frontier, with 90% of the bottomlands in the interior undeveloped.

The following table shows property tax rates for South Carolina and Mississippi. Note that many local town and county assessments effectively doubled the tax rates reported in the table. These taxes were still levied upon the landowners’ own sworn testimony as to the value of their land, which remained the dubious and exploitable system used by wealthy landholders in the South well into the 20th century.

Called upon to pay taxes on their property, essentially for the first time, angry plantation owners revolted. The conservatives shifted their focus away from race to taxes.[29] Former Congressman John R. Lynch, a black Republican leader from Mississippi, later wrote,

The argument made by the taxpayers, however, was plausible and it may be conceded that, upon the whole, they were about right; for no doubt it would have been much easier upon the taxpayers to have increased at that time the interest-bearing debt of the State than to have increased the tax rate. The latter course, however, had been adopted and could not then be changed unless of course they wanted to change them.[30]

Appendix

Notes

- Daniel W. Stowell (1998). Rebuilding Zion: The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863–1877. Oxford UP. pp. 83–84.

- Clarence Earl Walker, A Rock in a Weary Land: The African Methodist Episcopal Church During the Civil War and Reconstruction (1982)

- William W. Sweet, “The Methodist Episcopal Church and Reconstruction,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1914) 7#3 pp. 147–165 JSTOR 40194198 at p. 157

- Donald Lee Grant (1993). The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia. U. of Georgia Press. p. 264.

- Foner, Reconstruction, (1988) p 93

- Ralph E. Morrow, “Northern Methodism in the South during Reconstruction,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1954) 41#2 pp. 197–218, quote on p 202 JSTOR 1895802

- Ralph E. Morrow, Northern Methodism and Reconstruction (1956)

- Stowell, Rebuilding Zion: The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863–1877, pp 30–31

- Robert D. Clark, The Life of Matthew Simpson (1956) pp 245–67

- Fredrick A. Norwood, ed., Sourcebook of American Methodism (1982), p. 323

- William W. Sweet, “The Methodist Episcopal Church and Reconstruction,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1914) 7#3 pp. 147–165, quote on p 161 JSTOR 40194198

- Victor B. Howard, Religion and the Radical Republican Movement, 1860–1870 (1990) pp 212–13

- Morrow (1954) p 205

- Wilson Fallin Jr., Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama (2007), pp 52–53

- Anderson, James D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. U of North Carolina Press. p. 4.

- Anderson 1988, pp. 6–15.

- Tyack and Lowe. “The constitutional moment: Reconstruction and Black education in the South.” (1986):

- William Preston Vaughn, Schools for All: The Blacks and Public Education in the South, 1865—1877(University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- Foner 365–8

- Franklin 139

- Lynch 1913.

- B. D. Mayberry, A Century of Agriculture in the 1890 Land Grant Institutions and Tuskegee University, 1890–1990 (1992).

- Foner 387.

- Franklin pp 141–48; Summers 1984

- Stover 1955.

- Franklin pp. 147–8.

- Foner 375.

- Foner 376.

- Foner 415–16

Bibliography

- Anderson, James D. (1988). The Education of Blacks in the South, 1860–1935. U of North Carolina Press.

- Clark, Robert D., The Life of Matthew Simpson (1956).

- Fallin, Wilson Jr., Uplifting the People: Three Centuries of Black Baptists in Alabama (2007).

- Foner, Eric (2014). “Introduction to the 2014 Anniversary Edition”. Reconstruction Updated Edition: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-18.

- Franklin, John Hope. Reconstruction after the Civil War (1961), 280 pages.

- Grant, Donald Lee (1993). The Way It Was in the South: The Black Experience in Georgia. U. of Georgia Press.

- Howard, Victor B., Religion and the Radical Republican Movement, 1860–1870 (1990).

- Mayberry, B. D., A Century of Agriculture in the 1890 Land Grant Institutions and Tuskegee University, 1890–1990 (1992).

- Morrow, Ralph E., “Northern Methodism in the South during Reconstruction,” Mississippi Valley Historical Review (1954).

- Norwood, Fredrick A., ed., Sourcebook of American Methodism (1982).

- Sweet, William W., “The Methodist Episcopal Church and Reconstruction,” Journal of the Illinois State Historical Society (1914).

- Stowell, Daniel W. Rebuilding Zion: The Religious Reconstruction of the South, 1863–1877.

- Vaughn, William Preston, Schools for All: The Blacks and Public Education in the South, 1865—1877 (University Press of Kentucky, 2015).

- Walker, Clarence Earl, A Rock in a Weary Land: The African Methodist Episcopal Church During the Civil War and Reconstruction (1982).

Originally published by Wikipedia, 01.30.2019, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.