The overcrowded vessel’s crossing took more than two harrowing months.

By Craig Lambert

Deputy Editor

Harvard Magazine

In 1620, the Mayflower plowed across the Atlantic through headwinds and ocean currents at an incredibly slow two miles per hour. The overcrowded vessel’s crossing took more than two harrowing months. On the way, its 102 passengers witnessed an astonishing scene. During a fierce storm, an indentured servant named John Howland had come topside for fresh air when the ship rolled violently, casting him into the raging sea. He sank well beneath the waves. Such a fate almost certainly meant death by drowning. Yet, somehow, Howland had managed to grab a halyard on his way overboard, and desperately clung to it long enough for the crew to haul him back to safety.

Howland not only made it to America and worked off his indenture, but married a pretty young woman in the new colony named Elizabeth Tilley. They produced ten children, who begat 88 grandchildren, from whom an estimated two million Americans descended over the next four centuries. These included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Joseph Smith, Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Humphrey Bogart, Chevy Chase, and both Presidents Bush.

Howland’s story suggests the seminal power of the handful of Pilgrims who landed in Plymouth, near Cape Cod, in the late fall of 1620. Every culture invents creation myths to answer the questions, Where did we come from, What got us here? Such myths mingle tall tales with, at times, a seasoning of fact.

For American culture, the story of the Pilgrims, including their “first Thanksgiving” feast with the local Native Americans, has become the ruling creation narrative, celebrated each November along with turkey, pumpkin pie, and football games. The Pilgrims and Plymouth Rock have eclipsed the earlier 1607 English settlement at Jamestown, Virginia, as the place where America was born.

A new documentary, The Pilgrims, written and directed by Ric Burns and made with the help of a production grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities, airs on PBS’s American Experience this November 24 and again on Thanksgiving night. Its retelling of the Pilgrims’ adventure and ordeal sheds new light on why their story became the creation myth that we, as a people, adopted. It draws on the unique, nearly lost history, Of Plymouth Plantation, written by William Bradford, the new colony’s governor for more than 30 years, whom the late actor Roger Rees portrays from a script derived from Bradford’s book.

Filmmaker Burns interviews several scholars, who show how the reality of the Pilgrim experience diverged in several ways from images embedded in the public imagination. For example, “the story of the Pilgrims’ Thanksgiving has Native Americans welcoming them with open arms,” says Kathleen Donegan, a Berkeley English professor interviewed in The Pilgrims whose book Seasons of Misery: Catastrophe and Colonial Settlement in Early America was a source for the film. “It has been translated into this multicultural festival. But just as the Pilgrims don’t represent all English colonists, the Wampanoags, who feasted with them, don’t represent all Native Americans. The Pilgrims’ relations with the Narragansetts, or the Pequots, were completely different.”

Clearly, the story of a “multicultural festival” happening in newborn America resonates with the national ideology of inclusiveness. The Pilgrims did embody elements that took root in American culture, and this helps explain why, in retrospect, we call them our founders. The forces that shaped their lives also remain in place today. In that sense they are almost modern characters: Replace their wide-brimmed hats, doublets, and petticoats with baseball caps, T-shirts, and jeans, and they might easily blend into a homeschooling support group or a Tea Party rally.

The image of intergroup harmony and tolerance is naturally appealing to an immigrant country like America. Many imagine that the Pilgrims left the Old World behind to worship as they pleased and start a new country imbued with religious freedom, an ideal later codified in the First Amendment. Nothing could be further from the truth.

“A big misconception is that they were for religious freedom and liberty,” says Donegan. “Actually, the Pilgrims saw the world as a wilderness, in which the one right way of practice toward God might cultivate a garden—and you needed a hedge around that garden to protect it from the wilderness. They were terrified of contamination. The Pilgrims were not for freedom of religion. Quite the opposite: They had very specific ideas about how to worship God, and were intolerant of deviations.” Historian Pauline Croft of the Royal Holloway University of London declares in the film, “One might say, if you wanted to be critical, they’re religious nutters who won’t settle for anything except the most literal reading of the Bible. They want to transform a nation-state into something that resembles what they take to be a Godly kingdom.”

Purists, by definition, are extremists, and it’s no accident that many in England dubbed those who wanted to reform the Church of England “Puritans,” which “was always a derisive term,” Donegan explains. “The Mayflower pilgrims were the most extreme kind of reformers. They called themselves Saints, but were also known as Separatists, for their desire to separate themselves completely from the established church. They were extremely hot Puritans who saw the Church of England as hopelessly corrupt and felt they had to leave it to get back to a pure and honest church.” Separatists viewed the church’s hierarchy—and its holidays, rituals, vestments, and prayers—as obstacles interposed between people and God. In truth, “they were on a journey towards purity,” historian Susan Hardman Moore of the University of Edinburgh says in the film. “That’s what they sought; that’s what took them out of England.” The Separatists’ devotion to Scripture as the untrammelled source of faith resembles that of today’s religious fundamentalists, who venerate the literal word of God as found in the Bible.

Ironically, the most popular translation of that Bible, the King James version, came to be under a monarch who, in a sense, drove the Pilgrims from England. It was one thing to disagree with the church hierarchy, but the political problem was that the head of the Church of England was also the reigning king. And James I, who came to power in England in 1603, was a strong believer in unity when it came to his church; he had no patience with religious rebels or heterodox churches. “Anyone who separates from the church is not just separating from the church, but they’re separating from royal authority,” explains Michael Braddick, a historian at the University of Sheffield, in the film. “And that’s potentially very dangerous.”

You could be fined 20 pounds—equivalent to $9,000 today—for not attending services at the official church. Those who persisted faced imprisonment. After the Act Against the Puritans of 1593, Queen Elizabeth added banishment. “I think, with James, the next step could have been death for these people,” historical novelist Sue Allan asserts in the film. “He was newly to the throne—not popular. He wasn’t going to have any dissenters. So I really think that these folk were risking everything.”

With the handwriting on the wall, in 1608, the future Pilgrims exiled themselves to Amsterdam, where the Dutch had greater tolerance for radical Protestants. Soon they decamped southward for Leiden, a textile center where they formed a little English-speaking immigrant community and worshiped God as they pleased, unmolested. But adults and children alike, who’d been farmers in England, now toiled from dawn to dusk, six or seven days a week, weaving cloth in the textile factories. Even with such hardships, the Pilgrims later regarded their Leiden years as a type of “glory days,” whose difficulties were nothing compared with the ordeals they faced in America.

By 1617, the Separatists were getting anxious to move again. “Their biggest concern after a decade in this foreign land was that their children were becoming Dutch,” Nathaniel Philbrick, the author of Mayflower, another source for The Pilgrims, explains in the film. “They were still very proud of their English heritage. They were also fearful that the Spanish were about to attack again.” Indeed, a conflict was building between Spain’s Catholic king and European Protestant powers, which would soon embroil the continent in the Thirty Years’ War. Radical Protestants viewed this as a battle between the forces of good (Protestantism) and evil (Roman Catholicism), little short of Armageddon. “Everything seemed to be on the edge of complete meltdown,” Philbrick says. “And so they decided it’s time to pull the ripcord once again. Even if it meant leaving everything they had known all their lives.”

Many in the Leiden group made the wrenching decision to leave all behind—even children, in some cases—and try for a new start across the ocean. They determined to settle near the mouth of the Hudson River, not far from present-day New York City. A London broker, Thomas Weston, approached them in early 1620 and said he’d arrange financing for a passage to the New World. His investors hoped the voyagers would harvest profitable resources like beaver pelts from the virgin territory. The commercial motives behind the Mayflower voyage receive fairly short shrift in most textbooks, but they may well be another aspect of the Pilgrims’ enterprise that dovetails with American society, given that the United States has become the most successful capitalist economy on earth.

The right time to sail would have been early spring, giving the voyagers time to sow crops and build shelters during warm weather. But, by June, Weston had not raised the money and announced that his backers were getting cold feet: They were insisting that dozens of non-Separatist outsiders go with them. This was, of course, appalling to the cultic Separatists, who divided their own from these others by the categories saints and strangers. Yet they had no resources, and no choice.

The Mayflower’s manifest made an unlikely expeditionary force. Fewer than fifty were adult men, many of mature years, while at least thirty were children and nearly twenty women, three of them pregnant. They did not sail from Plymouth harbor until the disastrously late date of September 6, assuring that they would arrive in America after the growing season and at the onset of winter. Two had died by the time the crew sighted Cape Cod—two hundered miles off course, with no reliable charts—on November 9.

Predictably, there had been friction between the saints and strangers. Nonetheless, before disembarking on November 11, 41 of the adult men signed a simple agreement, hardly more than a sentence long, to band together into a “civil body politic” with the power to enact laws. This document, known as the Mayflower Compact, became a touchstone, years later, for the Plymouth Colony’s Book of Laws, which affirmed that, in a time of crisis, a monarch’s authority could be set aside, but the consent of the governed could never be. A seminal document, indeed.

Right from the start, the death rate was awful. Mortality had been enormous at the Jamestown colony, where by 1620 nearly 8,000 people had arrived, although the settlement was struggling to keep its population above a thousand. Bradford’s history recalled the Pilgrims’ anticipation of “a hideous and desolate wilderness, full of wild beasts and wild men.” Ferrying in supplies from the ship meant wading through ice-cold water, at one point with sleet glazing their bodies with ice. The first winter, people died from dysentery, pneumonia, tuberculosis, scurvy, and exposure, at rates as high as two or three per day. “It pleased God to visit us then with death daily,” Bradford wrote.

The living were hardly able to bury the dead, let alone care for the sick. By spring, half of them had perished, and “by all rights, they all should have died, given how ill prepared they were,” says Philbrick. Yet they survived, and the Pilgrims’ story is as much one of survival as of origins. They were also inventive enough, as Donegan notes, to prop up sick men against trees outside the settlement, with muskets beside them, as decoys to look like sentinels to the Indians.

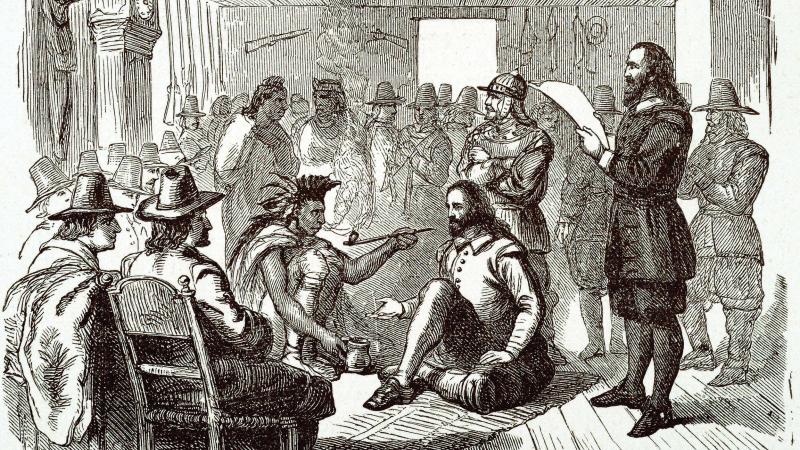

Early on, the settlers repelled an attack by Native American warriors—muskets against arrows, in a skirmish that presaged the continent’s future. Yet, in March, a lone Indian warrior named Samoset appeared and greeted the settlers, improbably, in English. Soon, the Pilgrims formed an alliance with the Wampanoags and their chief, Massasoit. Only a few years before, the tribe had lost 50 to 90 percent of its population to an epidemic borne by European coastal fisherman. Devastated by death, both groups were vulnerable to attack or domination by Indian tribes. They needed each other.

With spring, under the careful guidance of a Wampanoag friend, Tisquantum, the settlers planted corn, squash, and beans, with herring for fertilizer. They began building more houses, fishing for cod and bass, and trading with the Native Americans. By October they had erected seven crude houses and four common buildings. And, as autumn came, the Pilgrims gathered to in a “special manner rejoice together after we had gathered the fruit of our labors,” wrote one of their number, Edward Winslow. Bradford made no mention of it.

That was the first Thanksgiving. There is no record of an invitation to the Wampanoags, but Massasoit appeared at the feast with ninety men. They stayed for three days, and went out and bagged five deer to add venison to the menu. They played games together. This was the humble affair that, centuries later, President Abraham Lincoln made an official American holiday, perhaps the most beloved one of all.

“We love the story of Thanksgiving because it’s about alliance and abundance,” Donegan says in the film. “But part of the reason that they were grateful was that they had been in such misery; that they had lost so many people—on both sides. So, in some way, that day of thanksgiving is also coming out of mourning; it’s also coming out of grief. And this abundance that is a relief from that loss. But we don’t think about the loss—we think about the abundance.”

“It’s a very humble story of people who don’t have much, who suffer, and who have a communitarian ideal,” she adds. “It’s a very interesting narrative for a superpower nation. There is something sacred about humble beginnings. A country that has grown so rapidly, so violently, so prodigiously, needs a story of small, humble beginnings.”

Originally published to the public domain by Humanities, the Magazine of the NEH 36:6 (November/December 2015).