Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 08.31.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

Illinois was never a slave state, but there were struggles within the state between pro-slavery and anti-slavery forces. Article 6 of the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 stated that slavery would not exist in the states that would be created from that territory. Many officials in Illinois were pro-slavery and prevented free African-Americans from having full citizenship through the Black Codes. Additionally, the Illinois General Assembly took actions that were not sympathetic to the anti-slavery cause. For example, in 1837, a resolution was passed which condemned abolitionist societies. Despite the unwelcome atmosphere, active groups of citizens in Illinois continued to fight against slavery, organized themselves into abolitionist societies, and eventually joined with political parties in opposition to the institution of slavery.

During the 1830s, active societies formed throughout the state in order to combat slavery. Many of the founding members were religiously motivated, and their views on slavery were based on their religious beliefs. Some of the strongest anti-slavery societies formed in the northeastern counties of the state. The Illinois Anti-Slavery Society formed in the year 1837. By 1838, there were thirteen anti-slavery societies in Illinois. That same year, the murder of Elijah Lovejoy, a prominent abolitionist newspaper editor, by a pro-slavery mob in Alton, Illinois proved to be a pivotal moment in the movement. The actions of the “mob” were often influential in helping to win support for the anti-slavery movement. One slave owner stated, “Every drop of Lovejoy’s blood will spring up a full grown abolitionist.”

Abolitionists regularly used newspapers, mass meetings, speeches, and conventions to disseminate their message throughout Illinois. Many conductors on the Underground Railroad were central actors in the movement in Illinois. The Illinois anti-slavery movement joined with the Liberty Party in the 1840s and eventually ran candidates for office. As national politics became more volatile in the 1850s, the Illinois anti-slavery movement responded by resisting the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, responding to politically charged events in Kansas, and continuing to push abolitionist candidates into state and national political arenas. The abolitionists were determined to destroy the institution of slavery through any means available to them.

This collection focuses on the actions taken by abolitionists in Illinois and their reactions to national policies.

Abolitionist Societies: Their Philosophies and Actions

Overview

Throughout the nation, abolitionist societies were forming in the 1830s. In the Old Northwest, despite the fact that slavery had been excluded from the states that formed from the Northwest Territory, there was still a strong current of abolitionism. The abolitionists attacked slavery on moral grounds through an interpretation of natural rights, and on economic grounds. They tried to use persuasive tactics, often written, to convince others of the evils of slavery. Many of these societies grew over time, and some were more effective than others.

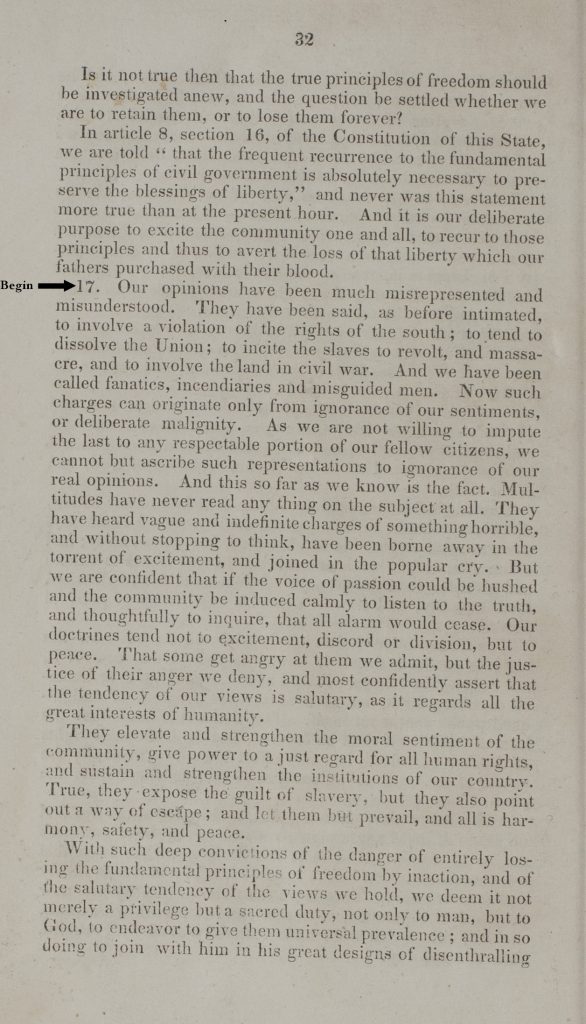

Proceedings of the Illinois Anti-Slavery Convention

The Illinois Anti-Slavery Convention met in Upper Alton from October 26 to 28, 1837, and was open to all people who were interested in attending. Many opponents of the abolitionist movement attended. The beginning of the meeting was wrought with conflicts between the two groups and marked by interference from the opponents to the movement. The meeting was eventually moved to the home of Thaddeus Hurlbut, an ally of the movement, and proceedings continued. The abolitionists laid out their purpose, defined their beliefs, and elaborated on the course that they planned to take.

Alton Trials

Two weeks after the Anti-Slavery Convention in Upper Alton, there was an attack on a printing press at a warehouse in Alton, Illinois. The press was an important vehicle for abolitionist messages, and despite the attack Elijah Lovejoy continued to write strong abolitionist messages despite numerous threats on his life. Lovejoy had moved to Alton from Missouri because he believed that he would meet less resistance for his views in a free state. However, after moving to Illinois, Lovejoy’s printing press was attacked and destroyed three times. His beliefs made him the target of the mob, and on November 7, he was killed as he defended his press with other supporters. This violent incident is not the only example of abolitionist ideas being met with the anger of the mob. The shock of Lovejoy’s murder acted as a catalyst for growth in the movement. The trial proceedings were published because many people wanted to understand the outcome and significance of the attack and its aftermath. The trial also raised important questions about freedom of the press and the dangers of mob rule.

“Slavery the Cause of Hard Times”

Zebina Eastman was an important abolitionist newspaper editor in Illinois. He was the editor of The Genius of Liberty and worked with Benjamin Lundy to edit the paper The Genius of Universal Emancipation. Eventually, he edited Chicago’s Western Citizen, which became essential to the movement in the Old Northwest from 1842 to 1853. The same press that published Western Citizen published The North-Western Liberty Almanac, a collection of abolitionist writings, for the years 1846 and 1847. The Almanac has a wealth of information about topics that range from annual lunar eclipses, changes in postage rates, entries on elementary anti-slavery principles, arguments for emancipation, discussions of natural rights, political commentary on the annexation of Texas, and a discussion of the economic effects of slavery. This entry is entitled, “Slavery the Cause of Hard Times.”

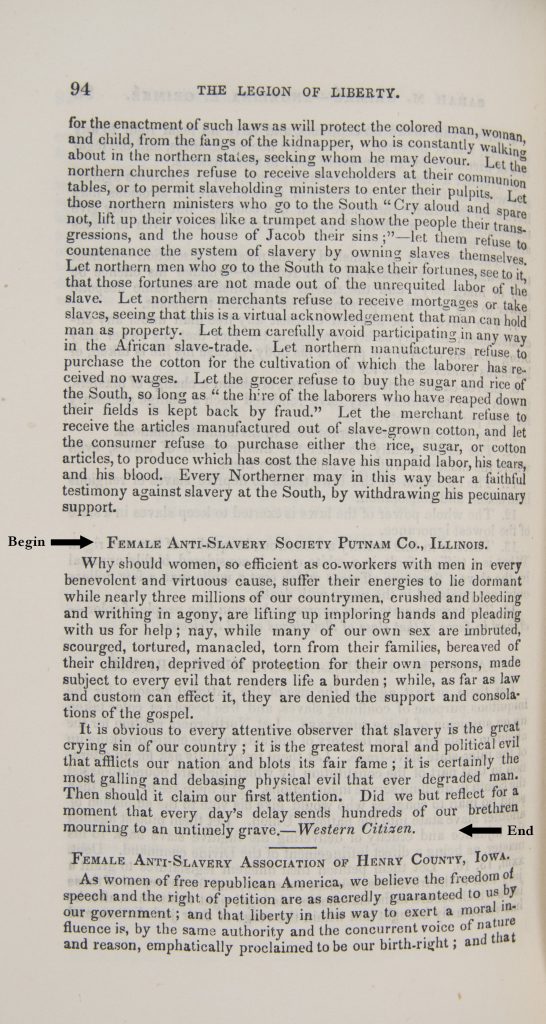

“Female Anti-Slavery Society, Putnum Co., Illinois”

The Legion of Liberty and the Force of Truth was published by the American Anti-Slavery Society in 1857 as a collection of writings from many important leaders throughout history on the issue of slavery, as well as a collection of the published work of abolitionists throughout the country. Many women in Illinois were active in the anti-slavery movement and formed anti-slavery societies in their local communities, including several groups in the Old Northwest. Some of the most central activists advocated for the participation of women, and their participation increased in the 1840s. Female anti-slavery societies were instrumental in garnering support for the Liberty Party in the 1840s. Women circulated petitions, worked to bring an end to the Illinois Black Laws, and supported efforts to assist fugitives through the Underground Railroad.

Abolitionists Respond to the National Political Climate in the 1840s and 1850s

Overview

The work of abolitionist societies eventually began to address national political developments with different tactics aimed at challenging the growth of a slave system. While anti-slavery societies in Illinois had previously addressed slavery through actions such as printing newspapers, writing letters to government officials, circulating petitions, and aiding runaway slaves, the 1840s and1850s were characterized by increased reaction to, and participation in, national politics. Illinois abolitionists moved into a more national role with the formation of the Liberty Party, their publicized reactions to the annexation of new lands and their status as slave or free states, their resistance to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and their election to public offices.

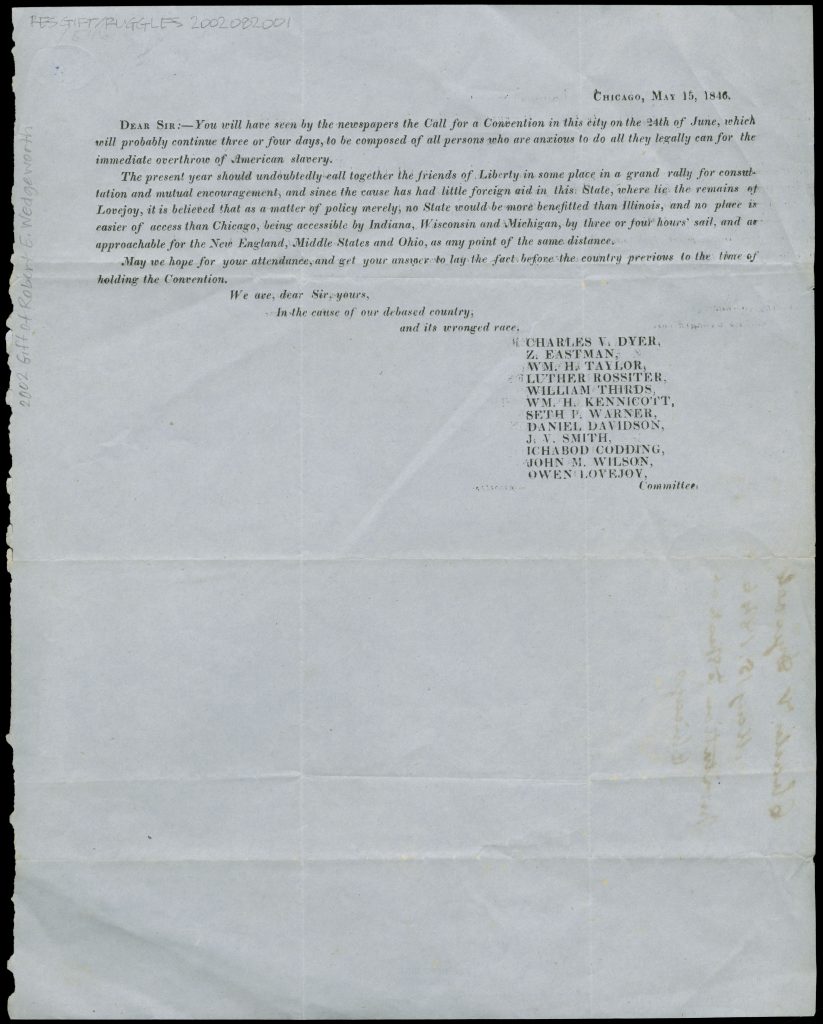

Invitation to attend the North-Western Liberty Convention

The Liberty Party formed in New York in 1840 to advance abolitionist goals through political means. Charles Volney Dyer, a physician, abolitionist, and conductor on the Underground Railroad, established a Chicago chapter of the Anti-Slavery Society to push forward the Liberty Party agenda in Illinois. Support for the Liberty Party increased in Illinois through the efforts of Dyer and Lovejoy, and actions of abolitionist societies became focused on promoting the party’s platform. Dr. Dyer and Owen Lovejoy attended a Liberty Party convention in New York in 1843 and led subsequent party-building efforts in Illinois, eventually combining the indebted Illinois Anti-Slavery Society with the Liberty Party altogether. The Northwestern Liberty Convention in June of 1846, attended by about 6,000 people, was organized in order to report on the status of the efforts of the Liberty Association in Illinois. These efforts included working toward the abolition of slavery, repealing the state’s Black Codes, and electing candidates to office.

The Weekly Chicago Journal and the Fugitive Slave Law

The Weekly Chicago Journal (later published as the Chicago Weekly Journal) covered local and national political developments. When the Compromise of 1850 was passed, including the Fugitive Slave Law, the local community responded with outrage. Chicagoans were brought face-to-face with the institution of slavery as fugitives were pursued in the North in keeping with the requirements of the law. Local newspapers attacked the law and its implications for northerners. Newspaper attacks provoked meetings, and those meetings resulted in organized resistance to the law.

- “Public Meeting” – October 7, 1850″: The African American community in Chicago was active in the anti-slavery movement. In response to the Fugitive Slave Law and its implications for free Blacks in the north, the African American community met at the African Methodist Episcopal Church in order to respond and organize themselves. They vowed to help escaped slaves to get to Canada and formed vigilance committees to guard against slave catchers.

- “The Council and the Slave Law”: October 28, 1850 On October 21, 1850, the Chicago Common Council passed a resolution stating that Chicagoans, including the police, would refuse to cooperate with the requirements of the Fugitive Slave Law. On October 23, Stephen Douglas, an Illinois senator and a supporter of the law, rushed to Chicago to try to quell the resistance. He spoke to the Common Council for three and a half hours in an effort to defend the law and refute the opposition. After his speech, the council voted to repeal the resolution.

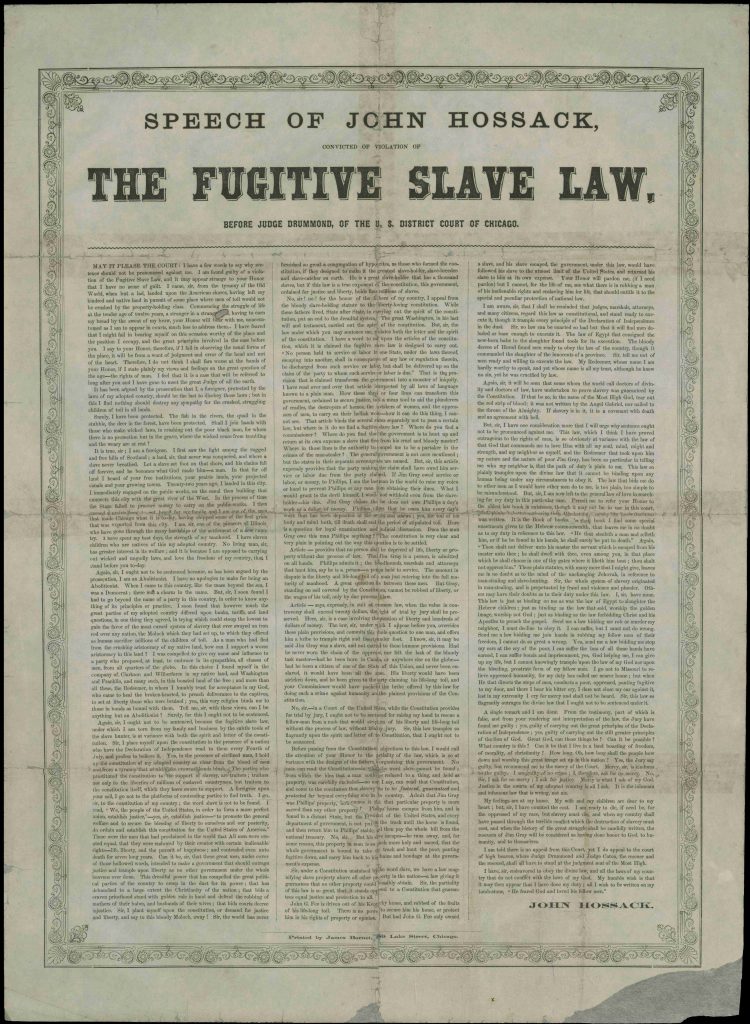

Speech of John Hossack

Efforts to assist fugitive slaves in their attempts to escape slavery, such as the Underground Railroad, increased in Illinois as support for the abolitionist cause grew. Illinois had already made harboring fugitives from slavery a crime in 1843 in the case of Eells v. Illinois. Countless abolitionists, including Dr. Richard Eells, Ichabod Codding, Zebina Eastman, and the Putnam County Female Anti-Slavery society assisted fugitives by giving them shelter, providing them with food and clothing, and helping them to find connections to other “conductors” on the route to freedom. One such “conductor” was John Hossack, an immigrant from Scotland. He had helped Jim Grey, a fugitive, escape from a courtroom in 1859. Hossack was ultimately convicted and sentenced, and gave this speech at his sentencing.

Constitution and By-Laws of the Illinois Woman’s Kansas Aid and Liberty Association

Another national political issue that led to a local response by Illinois abolitionists was the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 and the subsequent conflict that emerged in Kansas. Stephen Douglas had been instrumental in the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, which opened western lands to the possibility of slavery’s expansion by nullifying the Missouri Compromise. In his arguments to Congress in support of the law, he referred to the remarks that he had made in Chicago in 1850 in defense of the Fugitive Slave Law. Many abolitionists, newspaper editors, and others were vehemently opposed to the law and the results of the law, which resulted in a conflict known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The Illinois Woman’s Kansas Aid and Liberty Association was organized in 1856, the same year that the Republican Party was organized, to express their opposition to the conflicts occurring in Kansas and their desire to help the people of Kansas.

The Barbarism of Slavery

Illinois abolitionists had been attempting to insert themselves in local and national politics since the 1840s, and their cause was invigorated as national political developments seemed to continue to bolster the institution of slavery. Owen Lovejoy, like his brother Elijah, was a minister who became a strong advocate for the case against slavery. It was common knowledge that he was active in the Underground Railroad. He became frustrated with national political developments, eventually running for public office himself. He was elected to the state legislature in 1854. Lovejoy had been active in support of the Liberty Party and the Free Soil Party, and he was instrumental in the foundation of the Republican Party in Illinois. Beginning in 1856, he served four terms as a member of the House of Representatives as a Radical Republican. In response to Congressional Democrats’ pro-slavery arguments from the beginning of the session in late 1859, he asked for an hour on the agenda for April 5, 1860. After delivering this speech, he wrote to his wife, stating, “I preached the gospel pure and simple. It is the common topic of conversation this morning. They threaten to bring in a resolution to expel me but I think they will not be fools enough for that. It seems like old times to be in a storm.”

Selected Sources

- Tom Campbell. Fighting Slavery in Chicago: Abolitionists, the Law of Slavery, and Lincoln. Chicago: Ampersand, Inc., 2009.

- Helen Cavanagh. Antislavery Sentiment and Politics in the Northwest, 1844-60. Chicago, 1940.

- Stacey Robertson. Hearts Beating for Liberty: Women Abolitionists in the Old Northwest. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2010.

- Norman Dwight Harris. The History of Negro Servitude in Illinois. Chicago: A.C. McClurg and Co., 1904.

- Reinhard O. Johnson. The Liberty Party, 1840-1848: Antislavery Third-Party Politics in the United States. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

- Edward Magdol. Owen Lovejoy: Abolitionist in Congress. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1967.

- Joseph C. and Owen Lovejoy. Memoir of the Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy; who was Murdered in Defence of the Liberty of the Press, at Alton, Illinois, Nov. 7, 1837. New York: J.S. Taylor, 1838.

- Charles Mann. “The Chicago Common Council and the Fugitive slave law of 1850. An address read before the Chicago Historical Society at a special meeting held January 29, 1903.” Chicago, 1903.

- Harriet Martineau. The Martyr Age of the United States. Boston: Weeks, Jordan & Co., 1839.

- Willliam F. Moore Jane Ann Moore. Collaborators for Emancipation. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2014.

- ———. His Brother’s Blood: Speeches and Writings 1838-1864. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004.

- Owen Muelder. The Underground Railroad in Western Illinois. Jefferson: McFarland and Co., 2008.

- Carol Pirtle. Escape Betwixt Two Suns: A True Tale of the Underground Railroad in Illinois. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2000.

By Cristen Chapman

National Society of Daughters of the American Revolution, Chicago Chapter 2015

Newberry Teacher Fellow