We have to stop confusing outrage with virtue. Anger is not proof of innocence. Participation in a movement does not absolve anyone of scrutiny.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction: The Loudest Voices

There’s a cruel irony in the architecture of public outrage: the louder someone screams about morality, the more invisible their own shadows can become. We live in an age where accusation is theater, and virtue is a performance. And there’s perhaps no clearer stage for this than the chaotic, conspiratorial circus of QAnon, a movement that claims to defend children, yet often functions as a smokescreen for some of the very behavior it denounces.

The premise is seductive in its simplicity: there is a secret cabal of child traffickers, embedded in positions of power, and only a network of “awakened” citizens can stop them. It plays into primal fear, moral panic, and the comforting illusion that if we just believe hard enough, we’ll save the children. But the problem isn’t just that it’s false. The problem is that for certain individuals, the kind who deserve the closest scrutiny, movements like QAnon offer something much more dangerous than delusion: they offer cover.

In a world of suspicion, what better alibi is there than to join the mob calling for justice?

Moral Panic as a Shield

History has no shortage of loud, righteous movements masking quieter, darker agendas. In the 1950s, Senator Joseph McCarthy stoked fears of communist infiltration to elevate his power and crush dissent, all while fabricating most of his claims. The Satanic Panic of the 1980s destroyed lives on the back of false accusations of ritual abuse in daycares. In both cases, hysteria was weaponized, and those who opposed it were branded as sympathizers or traitors.

This isn’t new. What is new is the digital speed at which these panics now spread, and the scale of the communities they create. QAnon didn’t invent projection; it just optimized it for the algorithm.

When we think of predators, we often imagine isolation. A lurking figure in the shadows. But many are far more strategic. They embed themselves in institutions: churches, schools, charities, places where their proximity to innocence becomes a credential. Now, in the digital age, they embed themselves in outrage.

The trick is simple: make yourself look so opposed to something that no one would ever suspect you of it. Weaponize disgust. Perform morality. Join a movement that claims to protect children, then point to it like a badge. I can’t be one of them, they imply. Look how loudly I protest.

And history tells us, over and over, that sometimes, the loudest voices are the ones we should examine most closely.

The Cult of Outrage: QAnon’s Obsession with Child Abuse

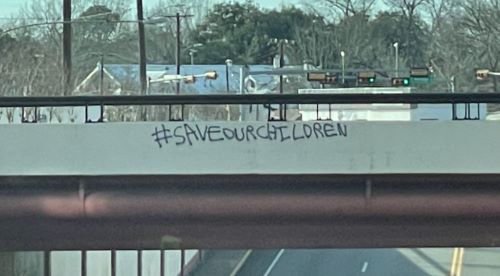

QAnon presents itself as a citizen-driven war against corruption and child exploitation. Its followers post slogans like “Save the Children,” flood social media with stories of underground trafficking rings, and accuse celebrities, politicians, and anyone opposed to the movement of being “part of the cabal.” It hijacks legitimate concern for child welfare and weaponizes it into a paranoid fantasy.

But here’s the truth: QAnon has done more to erode real anti-trafficking work than to support it.

Legitimate organizations on the ground, from Polaris to ECPAT to the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, have had to repeatedly clarify that QAnon’s claims are false, harmful, and disruptive. Resources are diverted. Law enforcement is flooded with conspiracy-driven tips. Real victims are buried under noise.

And behind the fog of all this performative rage are individuals who thrive on it, not to protect children, but to hide from the suspicion they deserve.

The Predator’s Playbook: Loud is Safe

There’s a chilling psychology at play here, and it’s not new. We’ve seen it in religious institutions where abusers hid behind pulpits. We’ve seen it in schools, in nonprofits, even in law enforcement. The predator doesn’t always run; sometimes they join. Sometimes they preach. Sometimes they march.

What QAnon offers is a powerful version of this camouflage. It is a ready-made identity that says: I care more than anyone else. I’m here to expose the evil. I could never be part of it.

But that’s the thing about projection: it’s not just a psychological defense, it’s often a strategic one.

The louder you scream about monsters, the more you convince people that you couldn’t possibly be one.

And when someone is already teetering on the edge of suspicion, maybe a minor accusation, maybe a troubling pattern, there’s no better escape route than joining the ranks of the accusers. It’s not about belief. It’s about misdirection.

The NAMBLA Model: Radical Rebranding of the Predator

This isn’t the first time predatory individuals have attempted to reframe themselves as advocates. In the 1980s and ’90s, the North American Man/Boy Love Association (NAMBLA) tried to position itself not as a haven for pedophiles, but as a misunderstood rights group. They used the language of liberty, justice, and “youth empowerment”, all to justify their abuse.

QAnon, ironically, is often comprised of people who would claim to crucify such organizations. Yet some of the behaviors echo the same playbook, hide behind a cause, use emotionally charged language, flood critics with accusations, and build an identity too publicly virtuous to question.

What better disguise than a self-declared warrior for the children?

The Real Cost: Collateral Damage and Broken Trust

While the movement yells about nonexistent tunnels and elite satanic rings, real children remain in danger, unnoticed, unheard, underserved. Survivors are disbelieved. Advocates are drowned out. Funding is misdirected. And worst of all, the public becomes desensitized.

When everything is a conspiracy, nothing is urgent.

And while that chaos unfolds, those who do harm are quietly watching. Some are even posting right alongside the loudest crusaders. They benefit from the noise. They move through it unseen.

This is the cost of allowing moral panic to replace moral clarity.

Real Faces Behind the Mask: When the Outrage is a Lie

The idea that predators might hide behind a cause like QAnon isn’t just theoretical; it’s proven.

- Matthew Taylor Coleman, a QAnon adherent and Trump supporter, murdered his two young children in 2021 with a spearfishing gun, claiming they had “serpent DNA” and were corrupted by cabal influence. His delusion was directly fueled by QAnon conspiracies, and his actions shattered the idea that those aligned with such movements are automatically protectors.

- Timothy Hale-Cusanelli, a Capitol rioter and vocal supporter of Trump’s MAGA movement, had a long history of racist, misogynistic, and sexually predatory comments. He once bragged about grooming young women and openly fantasized about violence, all while parading as a patriot.

- Andrew Taake, a self-described patriot and vocal QAnon supporter from Texas, was arrested for his violent participation in the January 6 Capitol insurrection. Beyond just attending the riot, Taake was filmed attacking officers with pepper spray and a metal whip. His online persona was filled with MAGA rhetoric and proclamations of moral outrage over “corruption” and “child abuse,” echoing classic QAnon themes. Yet behind that keyboard warrior façade was a man using violence to silence democracy, a predator of a different kind, cloaked in the language of virtue. Taake has been arrested on an outstanding child sex crimes charge. He had previously been charged with online solicitation of a minor stemming from a 2016 incident in which he allegedly sent sexually explicit messages to an undercover law enforcement officer who was posing as a 15-year-old girl.

- Adam Hageman, 26, was arrested in November 2020 after Homeland Security executed a search warrant of his home in Washington, DC. “During the search, he voluntarily unlocked his cell phone and provided access to an image vault containing child pornography to Homeland Security officials, according to a pre-trial detention memo. The vault contained at least 33 videos that appeared to contain sexually explicit depictions of children, according to the memo.” Hageman was sentenced to five-and-a-half years in prison.

- Sean Michael McHugh was convicted in 2010 on a state charge of unlawful sex with a minor, a 14-year-old girl. He was 23 at the time. He attacked officers and said they were “protecting pedophiles” on January 6th.

- Robert Morris, a former Texas megachurch pastor and ardent Trump supporter, faces five counts of lewd or indecent acts with a child.

These are not isolated cases. This list could go on and on to fill volumes, people who are part of movements like QAnon and shout their support for Trump from the rooftops as they rave against child predators, all the while actually being child predators. Over and over, men who proudly wore the MAGA hat and recited QAnon slogans were found to harbor deeply disturbing private lives. The wolves found in QAnon and MAGA a refuge, a cover, a place to hide and appear stridently against the very thing they are.

The horror isn’t just that they existed. It’s that they hid in plain sight, shouting about evil, while committing it. Each time someone reposted #SaveTheChildren or raged about imaginary trafficking tunnels, they layered one more mask over their own intentions.

They were counting on us never questioning the ones who scream the loudest.

Conclusion: Who Guards the Guardians?

We have to stop confusing outrage with virtue. Anger is not proof of innocence. Participation in a movement does not absolve anyone of scrutiny.

The real work of protecting children – the quiet, consistent, sober work – is done by people who don’t need to be watched because they’re too busy watching over others. And that work is under threat from movements like QAnon that turn concern into conspiracy, and weaponize virtue into spectacle.

If I don’t like something, even if I really don’t like it, then I just don’t do it and don’t involved myself with those who do. I don’t spend my days focused on it. I don’t join vast organizations and walk around with a megaphone to declare my allegiance to and with those against it. I just don’t do it. Pretty simple, right?

If we want to know where danger hides, we have to be willing to look behind the loudest masks. And if someone is screaming, “I would never,” we should always, always, ask, “Then why are you so desperate for us to believe it?”

Originally published by Brewminate, 07.28.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.