Amalric’s mystical and eschatological vision was both a challenge and a warning.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

Amalric of Bena (also spelled Amaury, Amauric, or Amalricus) was a French theologian and philosopher active in the late 12th and early 13th centuries. Though little is known of his personal life, his ideas left an enduring and controversial mark on the history of medieval thought. Often lumped together with the “heretics” of his time, Amalric is best remembered as the intellectual progenitor of the Amalricians, a sect that emerged in the early 13th century and was condemned by the Church as dangerously pantheistic. His work intersected with major philosophical and theological currents, including Neoplatonism, Augustinianism, and the nascent Scholasticism that characterized medieval universities. In many ways, Amalric stands as a liminal figure—both shaped by the intellectual traditions of his time and pushing against their boundaries in ways that anticipated the spiritual radicalism of later centuries.

Background and Intellectual Context

Amalric of Bena emerged as a thinker during a pivotal period in the intellectual history of medieval Europe, when the foundations of Scholasticism were being firmly established and the University of Paris was solidifying its role as a leading center of theological and philosophical inquiry. Born in Bennes near Chartres, likely around the mid-12th century, Amalric was shaped by the Chartres school of philosophy, a center known for its interest in Platonic and Neoplatonic thought as interpreted through Christian doctrine. This intellectual environment emphasized the harmony between faith and reason, drawing heavily on Augustine, Boethius, and later the rediscovered texts of Aristotle and the Neoplatonists. Amalric entered the University of Paris during its formative years, probably studying under or alongside leading scholars such as Peter Lombard, whose Sentences was becoming the foundational theological textbook of the era. His career as a master of arts placed him in the heart of theological development at a time when theological speculation was becoming increasingly systematized and institutionalized.1

The intellectual backdrop of Amalric’s thought was deeply indebted to Neoplatonism, especially as mediated through John Scotus Eriugena’s Periphyseon, a 9th-century treatise that proposed a dialectical and metaphysical unity between God and creation. Eriugena’s speculative theology argued that all things proceed from God and return to God, suggesting a cyclical, almost pantheistic vision of the cosmos. Amalric seems to have adopted and radicalized this vision, advancing a metaphysical position that did not merely locate God in all things but posited that all things are God.2 This distinction is subtle but radical: it collapses the ontological boundaries that define traditional Christian metaphysics and renders the doctrine of creation ex nihilo problematic. By embracing a theology of immanence, Amalric placed himself at odds with the dualistic framework of Augustinian orthodoxy, which stressed the transcendence and separateness of the Creator from creation. His metaphysical monism would eventually provoke ecclesiastical alarm, but it was not without precedent in earlier Christian mysticism.

Amalric’s era also witnessed the early phases of the Aristotelian revival, though he seems to have remained more firmly within the Platonic-Augustinian current. Through the 12th century, Aristotelian logic and metaphysics—transmitted via Arabic commentaries—were increasingly shaping theological debate. Thinkers like Adelard of Bath, William of Conches, and later Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas would integrate Aristotelian categories into Christian doctrine. Yet this process was gradual and contested, and many theologians still leaned heavily on the spiritual metaphysics of Augustine and Pseudo-Dionysius.3 Amalric’s rejection of a rigid Creator/creation distinction and his emphasis on divine immanence place him closer to the speculative Neoplatonism of Eriugena and Joachim of Fiore than to the more rationalistic Aristotelianism that would dominate later Scholasticism. This made Amalric a transitional figure—one who, rather than conforming to the rising norms of academic theology, hearkened back to older models of mystical speculation even as he studied within the most prestigious university of his day.

The spiritual climate of the late 12th century was marked by growing dissatisfaction with institutionalized religion and a renewed interest in direct, mystical experience of the divine. This was the age of charismatic reformers and apocalyptic visionaries, including Joachim of Fiore, whose idea of three historical “ages” (of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit) provided a model for understanding divine history as a progressive revelation.4 Amalric may have been influenced by this vision, developing a theological framework that saw traditional Church structures as temporary and ultimately to be transcended in favor of a more interior, spiritual knowledge of God. His teachings reportedly emphasized the coming of a new age in which human beings, fully united with God, would no longer require the mediation of priests or sacraments. This eschatological impulse placed him in proximity with later mystical and spiritualist movements, such as the Brethren of the Free Spirit and even, arguably, aspects of Protestant thought. Though Amalric himself left no substantial corpus, the movement that grew around his ideas—the Amalricians—testified to the widespread appeal of these ideas among both clerics and laypersons disenchanted with ecclesiastical orthodoxy.

Amalric of Bena must be understood within the context of the complex interplay between mystical theology, philosophical monism, and institutional authority in the High Middle Ages. His intellectual formation at Paris and his affinity for Neoplatonic and Augustinian thought positioned him at a moment of transition, as Scholasticism began to dominate theology with its logical precision and Aristotelian categories. Amalric’s speculative vision, far from being a mere deviation or heresy, reveals the undercurrents of theological creativity that persisted alongside the tightening dogmatic structures of the medieval Church. His ideas would prove too radical for the Parisian establishment, and his posthumous condemnation—along with the burning of his followers—was a sign of the increasing boundaries being drawn around theological speculation.5 Nonetheless, the questions Amalric raised about divine immanence, the nature of history, and the limits of ecclesiastical authority would remain potent long after his death.

Core Doctrines: Pantheism and the Unity of God and Creation

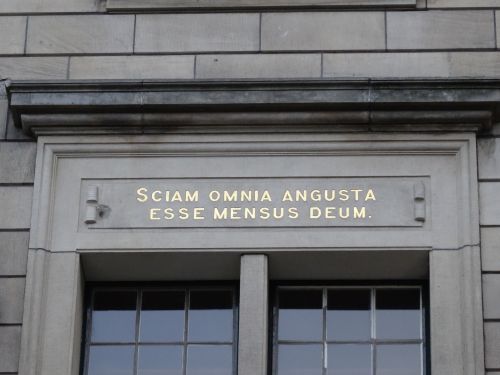

The central and most controversial tenet of Amalric of Bena’s theology was his assertion that “all that is, is God” (omnia esse Deum), a statement that struck at the very core of Christian metaphysical orthodoxy. While medieval Christian theology universally maintained a clear ontological distinction between the Creator and creation, Amalric’s view effectively collapsed that dualism, advocating instead a radical pantheism in which God and creation were not merely united in purpose or presence but were ontologically identical.6 This teaching marks a stark deviation from the Augustinian and Thomistic traditions, which insisted on God’s absolute transcendence. Instead, Amalric’s doctrine suggested a metaphysical monism, wherein all beings participate not just in the essence of God, but are God. While drawing on Neoplatonic ideas of emanation, he seemingly removed the hierarchy of being that distinguished between the divine source and its temporal manifestations.7 In doing so, Amalric eliminated any meaningful distinction between sacred and profane, heaven and earth, Creator and creature—asserting a universal divinity that inherently pervades all existence.

This pantheistic view was informed by and radicalized certain strands of Christian Neoplatonism, particularly those found in the works of John Scotus Eriugena. Eriugena’s Periphyseon had laid the groundwork for seeing all of nature as a theophany—a divine manifestation—and spoke of all things returning to God. Amalric pushed this further, erasing any transitional stages or ontological gradations and instead asserting that God does not exist apart from creation.8 This belief led him to interpret scripture allegorically and spiritually rather than literally or historically. For example, the Incarnation of Christ was not, in his framework, a unique and unrepeatable event in time, but rather a symbol of the divine presence within all people. This democratization of the divine radically undermined the exclusive mediating role of the Church and its sacraments. Amalric’s teaching thus laid the foundation for an egalitarian mysticism that, in effect, rendered ecclesiastical hierarchy and sacramental systems redundant, a position deeply troubling to the institutional Church.

Linked to his pantheism was Amalric’s trinitarian historicism, which proposed that the divine revelation had unfolded in three progressive stages: the Age of the Father, corresponding to the Old Testament and the Law; the Age of the Son, marked by the Incarnation and the establishment of the Church; and finally, the imminent Age of the Holy Spirit, in which human beings would live in direct union with God without the mediation of clerical structures.9 This notion closely resembles the teachings of Joachim of Fiore, although Amalric’s doctrine was arguably more mystical and less apocalyptic. The Age of the Holy Spirit was to be characterized by perfect spiritual liberty and an internalized experience of divinity, with no need for sacraments, scripture, or Church institutions. This eschatological view, while not explicitly revolutionary, carried dangerous implications: if divine fullness could be accessed individually and immediately, then the authority of the Church was not only unnecessary but potentially obstructive. This idea attracted followers among Parisian clerics and laity alike, leading to the formation of a sect known as the Amalricians, who developed and radicalized his views.

One of the most extreme doctrinal outcomes of Amalric’s theology was the assertion—likely by his followers, if not directly by Amalric himself—that a person who abides in love cannot sin, because they are already one with God.10 This belief stems logically from the premise that God is all and that those who realize this union are beyond moral or legal constraint. If one is ontologically identical with the divine, then human actions—however they appear to external judgment—are already harmonized with divine will. Such a claim echoes later mystical antinomianism, such as that found among the Brethren of the Free Spirit, where the elect are seen as beyond good and evil. It also undermines the entire penitential system upon which medieval ecclesiology was built. The Amalricians were accused of asserting that heaven and hell were not external realities but rather internal states of consciousness—ignorance being the only true damnation.11 While Amalric may not have personally advanced all these claims, his core doctrine of universal divinity opened the door to such conclusions.

Amalric’s teachings can be viewed as both a spiritual philosophy and a mystical anthropology. His pantheism was not a denial of the divine but an intensification of divine immanence—a theology of union that anticipated later Christian mystics such as Meister Eckhart. Yet it also transgressed the boundaries of acceptable speculation in an age increasingly marked by institutional control of doctrine. His teachings were condemned in 1204 by a council in Paris and posthumously anathematized. His bones were exhumed and reburied in unconsecrated ground, and his followers were interrogated, imprisoned, or executed.12 Despite these measures, Amalric’s ideas continued to resonate in later currents of Western mysticism, spiritual egalitarianism, and esoteric Christianity. His core doctrine—that the divine is not merely present in creation but identical with it—remains one of the most audacious and challenging theological visions of the medieval world.

Ecclesiastical Condemnation and the Amalricians

The teachings of Amalric of Bena, particularly his doctrine that “all things are God,” did not go unnoticed by the ecclesiastical authorities of his time. Though Amalric was a respected teacher during his lifetime, his ideas increasingly drew suspicion, especially as his students and followers began disseminating more radical interpretations. The turning point came around 1204 when Amalric’s doctrines were brought to the attention of the University of Paris and Church leaders. A commission of theologians investigated his teachings and concluded that they were heretical, primarily for their pantheistic implications and denial of the ontological distinction between Creator and creation.13 Although Amalric had already died—likely around 1204—his condemnation was not posthumous alone. The Church, in an unprecedented move, ordered the exhumation of his body from consecrated ground, symbolically denying him Christian burial rights. This action underscored the gravity with which the Church viewed his teachings and its determination to protect doctrinal boundaries during a period of increasing institutional consolidation.

In 1209, five years after Amalric’s death, the Fourth Lateran Council—convened by Pope Innocent III—officially anathematized his teachings. This council, one of the most important in medieval history, was deeply concerned with ecclesiastical discipline and the suppression of heresy. Amalric’s doctrines were declared heretical, and a series of harsh measures were enacted against his disciples, collectively known as the Amalricians.14 These individuals, many of whom were former students or intellectual sympathizers, had developed a sectarian movement that combined Amalric’s pantheism with eschatological and mystical ideas. The Amalricians believed that God was identical with the universe and that the Age of the Holy Spirit had arrived, in which the Church, scripture, and sacraments were no longer necessary. Their rejection of ecclesiastical authority and moral laws, coupled with their assertion that all things were divine, placed them well beyond the acceptable spectrum of medieval theological speculation.

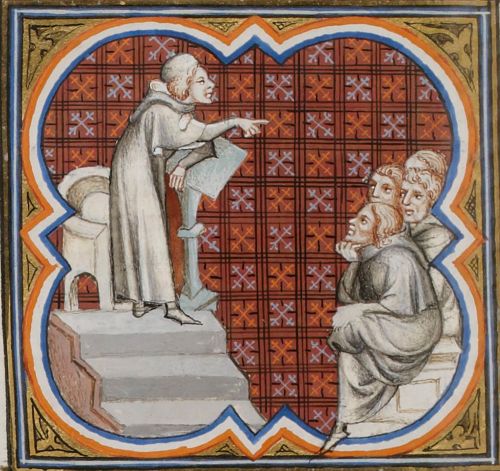

The response to the Amalricians was swift and severe. A group of them was arrested in Paris in 1210, and after interrogation and trial, ten members were condemned to death by burning. This was one of the earliest executions for heresy in medieval France, marking a pivotal moment in the history of ecclesiastical repression.15 Others were imprisoned or compelled to recant publicly. The University of Paris, still an emerging institution, found itself complicit in the persecution, as many of the accused had been connected to its teaching body. This was also one of the earliest examples of cooperation between academic theology and inquisitorial power, foreshadowing later medieval inquisitions. The incident demonstrates how Amalric’s speculative theology had evolved into a heterodox movement that was perceived not only as religiously dangerous but socially destabilizing. The fear that lay behind this suppression was not merely doctrinal deviation but the potential for widespread dissent and the undermining of ecclesiastical hierarchy.

Contemporary accounts of the Amalricians—largely written by hostile Church authorities—paint them as morally and doctrinally deviant, and it is difficult to distinguish Amalric’s authentic teachings from the later elaborations of his followers. Some sources allege that the Amalricians practiced antinomian behavior, including sexual libertinism, and denied the reality of sin for those united with God.16 While such claims may reflect polemical exaggeration, they also illustrate how Amalric’s theological pantheism lent itself to radical interpretations. The identification of God with all things could easily be construed—or misconstrued—as license for moral relativism and ecclesiastical rebellion. The response to Amalric and his followers was not just about the preservation of orthodoxy, but about maintaining the social and theological framework upon which medieval Christendom depended. The Amalrician crisis thus served as a catalyst for the Church to sharpen its mechanisms for identifying and suppressing dissent.

Despite the suppression, Amalric’s ideas continued to influence underground mystical and heterodox movements for generations. The Amalricians would later be cited as precursors to the Brethren of the Free Spirit, the Beghards, and even certain strains of Renaissance pantheism.17 The Church’s severe reaction illustrates both the boldness of Amalric’s vision and the threat it posed to the institutional order. His vision of a world suffused with divinity, in which ecclesiastical mediation was rendered obsolete, resonated with those who sought a more immediate and personal experience of God. Though Amalric himself may not have intended to found a sect or incite rebellion, his philosophical legacy could not be confined within the dogmatic structures of medieval orthodoxy. In condemning him, the Church both affirmed its authority and inadvertently acknowledged the enduring power of his radical theology.

Influence and Legacy

Although Amalric of Bena was condemned by the Church and posthumously discredited, the intellectual afterlife of his ideas proved remarkably resilient. His pantheistic vision, though suppressed during his lifetime and shortly after, found echoes in various mystical, esoteric, and even philosophical currents throughout the later Middle Ages and beyond. The radical assertion that God is identical with all being—omnia esse Deum—reverberated most clearly in the heterodox mystical movement known as the Brethren of the Free Spirit, which emerged in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries.18 The Free Spirit movement similarly proclaimed the divinization of the individual and the irrelevance of Church mediation, offering spiritual liberty that bordered on anarchism. Though direct transmission from Amalric to the Free Spirit groups is difficult to document, contemporary inquisitors and chroniclers often linked the two, attesting to a perceived ideological continuity. This perception suggests that Amalric’s theological innovations had entered the subterranean bloodstream of Western heterodoxy.

Amalric’s influence can also be discerned in the works of Meister Eckhart, the fourteenth-century Dominican mystic whose sermons and treatises sometimes bear an uncanny resemblance to Amalrician themes. Eckhart’s doctrine of the birth of God in the soul, and his assertion that in the ground of the soul there is no distinction between God and man, tread a fine line between orthodox mysticism and metaphysical pantheism.19 While Eckhart did not espouse Amalric’s systematic theology, and remained formally within the Church, the affinity in their language and metaphysical daring suggests that Amalric’s ideas continued to influence speculative thinkers, even in more moderate and nuanced forms. Moreover, Eckhart’s own posthumous condemnation in 1329 by Pope John XXII, for reasons related to the radical implications of his theology, demonstrates that the tensions Amalric exposed—between divine transcendence and immanence, between institutional authority and mystical experience—remained unresolved within the Christian intellectual tradition.

Beyond the mystical and heterodox traditions, Amalric’s legacy can be traced into the early modern period, particularly among Renaissance philosophers who began to revisit and reframe pantheism in philosophical rather than theological terms. The most prominent figure in this regard is Giordano Bruno, whose doctrine of an infinite, living cosmos suffused with divinity bears striking similarities to Amalric’s views.20 Bruno was familiar with medieval mystical currents and was likely aware, directly or indirectly, of Amalric’s controversial theology. Like Amalric, Bruno rejected a God who was spatially or ontologically distinct from creation, preferring a vision of divinity as an immanent presence within the universe. While Bruno couched his ideas in the language of cosmology and natural philosophy, his fate—burned at the stake in 1600—mirrored that of Amalric’s disciples, underscoring the enduring threat posed by pantheistic and non-dualist thinking to ecclesiastical orthodoxy.

Amalric’s reputation experienced a degree of rehabilitation in the context of modern philosophy, particularly during the Enlightenment. Thinkers such as Spinoza advanced a philosophical pantheism that echoed Amalric’s fusion of God and nature, although now presented in rationalist and geometric terms.21 Enlightenment historians, increasingly critical of the Church’s authoritarianism, began to reinterpret Amalric not as a heretic but as a tragic forerunner of modern religious liberty and metaphysical speculation. In some circles, he came to be seen as a proto-humanist, advocating a form of immanence that prefigured the dissolution of clerical authority. Nineteenth-century historians of ideas—especially in German Idealism—further explored his teachings as part of a broader tradition of speculative mysticism, linking him to the dialectical development of consciousness and spirit. Thus, the very ideas for which Amalric was once exhumed and condemned came to be appreciated as part of the evolution of Western thought.

In contemporary scholarship, Amalric of Bena has been re-evaluated as a significant, though controversial, figure in the intellectual history of the medieval world. Scholars such as Bernard McGinn and Matthias Riedl have emphasized not only the boldness of his theological vision but also his importance in mapping the boundaries of acceptable Christian thought. Amalric serves as a reminder that medieval theology was not a monolithic edifice but a dynamic and contested field, in which metaphysical innovation could coexist—however precariously—with institutional orthodoxy.22 His doctrines, while ultimately condemned, opened critical questions about the nature of God, the structure of the universe, and the possibility of human-divine union. The enduring fascination with his ideas—whether in mysticism, heresy, philosophy, or esotericism—testifies to the lasting impact of a thinker who dared to envision a cosmos wholly filled with God.

Conclusion

Amalric of Bena remains a marginal but fascinating figure in medieval intellectual history. Condemned by his contemporaries and largely erased from the canon, he nevertheless represents a significant moment in the dialectic between orthodoxy and heterodoxy, reason and mysticism, Church authority and individual inspiration.

Though the accuracy of the reports about his teachings must be taken with caution—since they often come from hostile sources—Amalric appears to have sought a synthesis of philosophy and theology that broke through the boundaries of established dogma. His pantheism was not born of irreverence, but of a profound desire to understand and experience the divine as radically present in all things.

In an era increasingly characterized by institutional rigidity and theological precision, Amalric’s mystical and eschatological vision was both a challenge and a warning: that the quest for divine truth could not be contained within dogma alone. Whether seen as a heretic, a prophet, or a philosopher, Amalric of Bena deserves recognition as one of the more daring thinkers of the Middle Ages—one whose thought, like so many condemned as heresy, reminds us of the tensions that lie at the heart of religious tradition.

Appendix

Endnotes

- M.-D. Chenu, Nature, Man and Society in the Twelfth Century, trans. Jerome Taylor and Lester K. Little (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968), 50–53.

- Guy G. Stroumsa, Hidden Wisdom: Esoteric Traditions and the Roots of Christian Mysticism (Leiden: Brill, 1996), 101–104.

- David Knowles, The Evolution of Medieval Thought (London: Longman, 1962), 110–113.

- Bernard McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism: Men and Women in the New Mysticism 1200–1350 (New York: Crossroad, 1998), 32–34.

- R. I. Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250 (Oxford: Blackwell, 1987), 155–158.

- McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, 31-33.

- Stroumsa, Hidden Wisdom, 106-109.

- Knowles, The Evolution of Medieval Thought, 117-120.

- Matthias Riedl, “A Heresy of the Holy Spirit: Amalric of Bena, Joachim of Fiore, and the Amalricians,” Church History 76, no. 2 (2007): 273–275.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 159-161.

- McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, 34.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 162.

- Knowles, The Evolution of Medieval Thought, 121-124.

- McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, 35.

- Moore, The Formation of a Persecuting Society, 163.

- Stroumsa, Hidden Wisdom, 111-113.

- Riedl, “A Heresy of the Holy Spirit”, 277-280.

- McGinn, The Flowering of Mysticism, 40-42.

- Richard Woods, Eckhart’s Way: The Mystical Theology of Meister Eckhart (New York: Paulist Press, 1986), 77–80.

- Hilary Gatti, Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 98–102.

- Frederick C. Beiser, The Sovereignty of Reason: The Defense of Rationality in the Early English Enlightenment (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 141–144.

- Riedl, “A Heresy of the Holy Spirit”, 281-283

Bibliography

- Beiser, Frederick C. The Sovereignty of Reason: The Defense of Rationality in the Early English Enlightenment. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996.

- Chenu, M.-D. Nature, Man and Society in the Twelfth Century. Translated by Jerome Taylor and Lester K. Little. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1968.

- Gatti, Hilary. Giordano Bruno and Renaissance Science. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999.

- Knowles, David. The Evolution of Medieval Thought. London: Longman, 1962.

- McGinn, Bernard. The Flowering of Mysticism: Men and Women in the New Mysticism 1200–1350. New York: Crossroad, 1998.

- Moore, R. I. The Formation of a Persecuting Society: Authority and Deviance in Western Europe, 950–1250. Oxford: Blackwell, 1987.

- Riedl, Matthias. “A Heresy of the Holy Spirit: Amalric of Bena, Joachim of Fiore, and the Amalricians.” Church History 76, no. 2 (2007): 269–294.

- Stroumsa, Guy G. Hidden Wisdom: Esoteric Traditions and the Roots of Christian Mysticism. Leiden: Brill, 1996.

- Woods, Richard. Eckhart’s Way: The Mystical Theology of Meister Eckhart. New York: Paulist Press, 1986.

Originally published by Brewminate, 05.27.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.