The origins of the theory are rooted in the medieval idea that God had bestowed earthly power to the king, just has He had given spiritual power and authority to the church, centering on the pope.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Divine Right of Kings is a political and religious doctrine of royal absolutism. It asserts that a monarch is subject to no earthly authority, deriving his right to rule directly from the will of God. The king is thus not subject to the will of his people, the aristocracy, or any other estate of the realm, including the church. The doctrine implies that any attempt to depose the king or to restrict his powers runs contrary to the will of God and may constitute treason.

The origins of the theory are rooted in the medieval idea that God had bestowed earthly power to the king, just has He had given spiritual power and authority to the church, centering on the pope. With the rise of nation-states and the Protestant Reformation however, the theory of Divine Right justified the king’s absolute authority in both political and spiritual matters. The theory came to the fore in England under the reign of King James I (1603–25). King Louis XIV of France (1643–1715), though Catholic, strongly promoted the theory as well.

The theory of Divine Right was abandoned in England during the Glorious Revolution of 1688–89. The American and French revolutions of the late eighteenth century further weakened the theory’s appeal, and by the early twentieth century, it had been virtually abandoned.

Background

A concept of Divine Right is also found in ancient and non-Christian cultures including Aryan and Egyptian traditions. In non-European religions, the king was often seen as a kind of god and so became an unchallengeable despot.

The Jewish tradition limited the authority of the Israelite kings with reference to the Mosaic law and the oversight of the prophets, who often challenged the kings and sometimes even supported rival claimants to the throne in God’s name. The ancient Roman Catholic tradition dealt with the issue of royal absolutism with the doctrine of the “Two Swords,” promulgated by Pope Gelasius I (late fifth century). Gelasius held that both the royal and priestly powers were bestowed by God, but that the pope’s power was ultimately more important:

There are two powers, august Emperor, by which this world is chiefly ruled, namely, the sacred authority of the priests and the royal power… You are also aware, dear son, that while you are permitted honorably to rule over humankind, yet in things divine you bow your head humbly before the leaders of the clergy and await from their hands the means of your salvation.

Thomas Aquinas allowed for the overthrow of a king (and even regicide) when the king was a usurper and thus no true king; but he forbade, as did the Church, the overthrow by his subjects of any legitimate king. The only human power capable of deposing the king was the pope. Toward the end of the Middle Ages philosophers such as Nicholas of Cusa and Francisco Suarez propounded similar theories. The Church was the final guarantor that Christian kings would follow the laws and constitutional traditions of their ancestors and the laws of God and of justice.

During the Renaissance, national powers asserted increasing independence from the papacy, and the Protestant Reformation further exacerbated the need of kings to justify their authority apart from the pope’s blessing, as well as to assert their right to rule the churches in their own realms. The advent of Protestantism also removed the counterbalancing power of the Roman church and returned the royal power to a potential position of absolute power.

Divine Right in England

What distinguished the English idea of Divine Right from the Roman Catholic tradition was that in the latter, the monarch is always subject to the following powers, which are regarded as superior to the monarch:

- The Old Testament, in which the authority of kings was limited with reference to the Law of Moses and could be rightly challenged and sometimes overthrown by the prophets speaking in the name of God

- The New Testament in which the first obedience is to God and no earthly king, but also in which the first “pope,” Saint Peter, commands that all Christians shall honor the Roman Emperor (1 Peter 2:13-17) even though, at that time, he was still a pagan.

- The necessary endorsement by the popes and the Church of the line of emperors beginning with the Constantine I and Theodosius I, later the Eastern Roman emperors, and finally the Western Roman emperor, Charlemagne.

The English clergy, having rejected the pope and Roman Catholicism, were left only with the supreme power of the king who, they taught, could not be gainsaid or judged by anyone. Since there was no longer the counter-veiling power of the papacy and since the Church of England was a creature of the state and had become subservient to it, this meant that there was nothing to regulate the powers of the king, who had become an absolute power. In theory, divine law, natural law, and customary and constitutional law still held sway over the king. However, absent a superior spiritual power, such concepts could not be enforced, since the king could not be tried by any of his own courts, nor did the influence of the pope hold any sway by this point.

The scriptural basis of the Divine Right of Kings comes partly from Romans 13:1-2, which states: “Let every soul be subject unto the higher powers. For there is no power but of God: The powers that be are ordained of God. Whosoever therefore resisteth the power, resisteth the ordinance of God: and they that resist shall receive to themselves damnation.”

n the English-speaking world, the theory of Divine Right is largely associated with the early Stuart reigns in Britain and the theology of clergy who held their tenure at the pleasure of James I, Charles I, and Charles II. One of the first English texts supporting the Divine Right of Kings was written in 1597-98 by James I himself before his accession to the English throne. Basilikon Doron, a manual on the duties of a king, was written by James I to edify his four year old son, Henry Frederick, Prince of Wales, affirming that a good king “acknowledgeth himself ordained for his people, having received from God a burden of government, whereof he must be countable.”

The conception of royal ordination by God brought with it largely unspoken parallels with the Anglican and Catholic priesthood, but the overriding metaphor in James’ handbook was that of a father’s relation to his children. “Just as no misconduct on the part of a father can free his children from obedience to the fifth commandment (to honor one’s father and mother), so no misgovernment on the part of a King can release his subjects from their allegiance.” James also had printed his Defense of the Right of Kings in the face of English theories of inalienable popular and clerical rights.

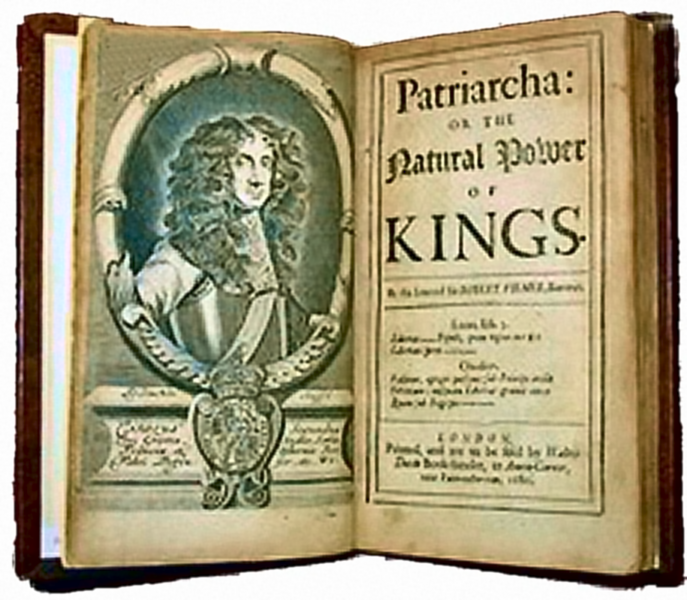

In the mid-seventeenth century, Sir Robert Filmer propounded the idea that the king was, in effect, the head of the state in the same sense that a father is the head of his family. In this theory Adam was the first king and Charles I stood in the position of Adam in England, with absolute authority to rule. John Locke (1632–1704) effectively challenged this theory in his First Treatise of Civil Government (1689), propounding the idea of a social contract between the ruler and his subject and affirming the principle that the people had the right to challenge unjust royal power. Locke’s ideas, including the principle of God-given rights of life, liberty and property, became seminal in the Glorious Revolution and its aftermath, and especially in the American Revolution of 1776.

Divine Right in France

In France, the chief theorist of Divine Right was Jacques-Bénigne Bossuet (1627–1704), bishop of Meaux and court preacher to Louis XIV. Like Filmer, Bossuet argued that kings received their power directly from God. Just as a father’s authority is absolute in a family, so is the king’s in the state. Bossuet asserted that “God establishes kings as his ministers, and reigns through them over the people.” He also stated that “the prince must be obeyed on principle, as a matter of religion and of conscience.” Those who argued otherwise were agents of evil opposed to the will of God.

Louis XIV agreed strongly with these aspects of Bousseut’s views, which conformed with his own ideal of himself as an absolute ruler: the so-called “Sun King.” He did not, however, always follow Bousseut’s preaching regarding Christian conduct and morality.

Bossuet, who as a bishop also owed obedience to the pope, found himself caught by his own doctrine in a paradox in 1682, when Louis insisted on his clergy making an anti-papal declaration. Bossuet was tasked to draft the document, and attempted to make it as moderate as he could. The pope, however, declared it null and void, and Bousseut died before he could publish his defense of his views in Defensio Cleri Gallicani.

French Enlightenment thinkers such as Montesquieu challenged Divine Right with the doctrine of the separation of powers, arguing that government is best conducted when the executive branch is checked and balanced by an independent legislature and judiciary. The theory of Divine Right in France was finally overthrown during the French Revolution.

After the American Revolution and the French Revolution, royal absolutism and the theory of Divine Right still lingered in some quarters, but it would only be a matter of time until the Divine Right was relegated to history.

References

- Butler, John A. James I and Divine Right. Tokyo: Renaissance Institute, Sophia University, 1999. OCLC 41418652.

- Daly, James. Sir Robert Filmer and English Political Thought. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1979.

- Figgis, John Neville. The Divine Right of Kings. Gloucester, Mass: P. Smith, 1970.

- Reynolds, Ernest Edwin. Bossuet. Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday, 1963.

- Schiel, Katy. Monarchy: A Primary Source Analysis. New York: Rosen Pub. Group, 2005.

- Wedgwood, C. V. The King’s Peace, 1637-1641. New York: Macmillan, 1955.

Originally published by New World Encyclopedia, 10.17.2008, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.