Originally published by Newberry Digital Collections for the Classroom, 09.26.2017, Newberry Library, republished with permission for educational, non-commercial purposes.

Introduction

The English Reformation was part of a European-wide phenomenon to reform the church which began in 1517 when legend has it that the German monk and theologian Martin Luther nailed 95 theses (propositions for discussion) to the door of the castle church at Wittenberg to be debated publicly. Chief among these was the church doctrine on indulgences. Indulgences were grants of a remission of punishment for sins committed. In the later Middle Ages indulgences became connected to the doctrine of purgatory, an in-between place in the afterlife where the souls of those who died in state of venial sin could be purged by the prayers and good works of the living. Luther’s objection to the doctrine was based on his reading of the letters of St Paul from which he concluded that no performance of rituals nor acts of piety could guarantee salvation and that no intermediary authority, priest, bishop, or pope of the church could stand between a human being and God.

Like reformers before him, Luther hoped to reform the church from within. His dispute, however, grew into a challenge to the church’s authority to determine legitimate interpretations of scripture and rituals of worship. Sola fide (“by faith alone”) and sola scriptura (“by scripture alone”) became the watchwords of Lutheran reform that salvation was based on faith and Biblical authority was the only standard for determining correct doctrine. By the early 1520s, Luther and his supporters had broken with the papal authorities, Luther was excommunicated, and German principalities had become embroiled in the conflict. By the middle of the sixteenth century, this protest, “Protestantism,” had three main doctrinal centers: the Lutherans in Germany; Zwinglians in Switzerland; and Calvinists in Geneva. Although the reformers were divided on many specific issues, they shared three common points of view: the removal of the papacy and the religious system he oversaw, an emphasis on a Bible-centered theology and spirituality, and the need for laity to be able to read Sacred Scriptures in the vernacular.

The Reformation in England was not removed from these events on the continent. Until the mid-twentieth century, the narrative of England’s Protestant nationalist triumph answered very neatly the question of how England became Protestant. Historians have since moved away from thinking in terms of the Reformation as a single, linear process that was inevitable. Most historians now accept that there was a “begrudging conformity” in public in England throughout the sixteenth century, as church legislation swung from the long reign of Henry VIII and his break with Rome, to Edward VI’s and Mary I’s relatively short reigns and their swings from radical Protestantism to Catholic restoration respectively. The Reformation as it unfolded in England can be understood as a tension between continuity and change.

What is a Protestant? What is a Catholic? Royal legislation made for quick changes in religious practice, but belief and acceptance of those changes occurred much more slowly. Compulsion and compliance by law by either a Protestant or Catholic prince did not equal assent or conversion by the population. As Protestant identity developed over time, so too Catholic identity was transformed. Historians have argued that practicality describes the response of most people toward the reformation. What was most practical for people to do—conform to the new ways or resist them? Not all Protestants nor all Catholics became martyrs for their faith. Everywhere there are elements of a lingering continuity with what had come before. The passage of time was in many ways as significant as the legislation mandated from on high.

All European rulers and states of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries used terror and torture as a tool of authority. Though Mary I is known in history and popular culture as “bloody Mary” for her execution of 284 Protestant martyrs, her father, brother and sister did not shy away from starving, beheading, hanging in chains, drawing and quartering their enemies, and burning heretics. Did the brutality of religious wars on the continent in the sixteenth century and in England in the seventeenth century lead to calls for religious toleration and a pluralistic society later in the seventeenth and eighteenth century? Some historians argue that a new attitude took root and people eventually came to live with the notion that universality and religious unity was not possible. Not that people became tolerant per se, but that they became tolerant of the fact that there would always be differences. In the sixteenth century religion and conformity to religion was a matter of public concern. By the eighteenth century, religion as a matter of private concern had taken root. The Protestant Reformation questioned and eventually uprooted the idea of a united Christendom and a universal church under the authority of the papacy that had been maintained by the western Church throughout the middle ages. The loss of unity splintered Christianity. In England, the break with Rome created a state church that was not independent of royal control. However, the state church splintered and could not maintain a unified religious identity, nor did it become part of a wider community of “international protestantism.”

Spirituality and Popular Piety in the English Church c. 1500

The English church at the end of the Middle Ages has been characterized as both vital and vulnerable. While there is a long-standing tradition of popular anti-clericalism in medieval England, glimpsed in literary works such as Langland’s Piers Ploughman and Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales, historians generally concur that there was a sense of satisfaction with the institutional church in the early sixteenth century.

The church in England was vast and it pervaded all aspects of life. As in other parts of medieval Europe, English life revolved around the church calendar and the liturgical seasons of preparation and feast: Advent, Christmas, and Epiphany; Lent, Easter, and Pentecost. Formal worship was centered on Sunday’s Mass and Eucharist, but daily prayer and rituals were knit tightly into the fabric of society. An individual’s life was marked out by church sacraments and rituals—baptism, communion, marriage, and death.

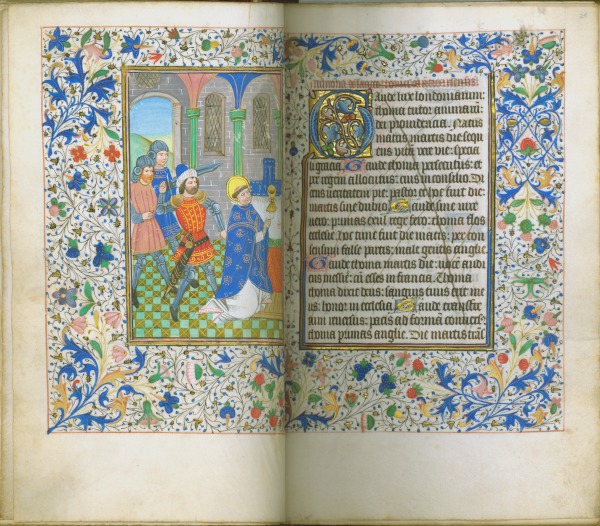

St Thomas of Canterbury was perhaps the most popular English saint in the later middle ages. His shrine and the pilgrimage to it were immortalized in Geoffrey Chaucer’s The Canterbury Tales. Thomas Becket (1118-1170) had been the archbishop of Canterbury under Henry II (1133-1189) in the twelfth century. According to the “Lyfe of St. Thomas” in Caxton’s 1509 “englyshed” edition of Jacques Voragine’s Golden Legend (c. 1260), Thomas had blocked the king’s actions in a series of contests over royal control of the English Church, and the jurisdiction of royal and ecclesiastical courts. Thomas used the papacy to thwart Henry’s slights to church prerogative and traditional rights. After one episode, Henry uttered words in anger against Becket in the company of his knights that led them to murder the archbishop on the altar of Canterbury cathedral.

Henry did public penance for the anger that prompted the killing. One of acts of penance was to establish an order of Carthusian monks to England. In 1215, his son, King John, in a failed contest with the nobles and churchmen of England signed the Magna Carta whose first article declares the liberty of the church of England.

In general historians agree that the majority of English men and women were content with the spirituality, piety, church apparatus and structure. Contentment, however, did not mean people were uncritical. Popular anti-clericalism that existed throughout the middle ages concerned resentment over tithes and the wealth of the church in general, but there was no widespread violence in England against its clergy.

Why Reform the Church? Henry VIII and the “First” English Reformation

The English Reformation did not come about because a mass of the population was dissatisfied with the church. At the outbreak of Luther’s challenge to the church in 1517, Henry VIII did not embrace Luther’s reform. In 1521, Henry VIII was granted the title “Defender of the Faith” by Pope Leo X for his Defense of the Seven Sacraments against Martin Luther’s continued attacks on the church’s theology and governance structures.

England’s Reformation was set in motion by Tudor dynastic problems. In the 1520s, Henry VIII had no legitimate male heir. Two sons born to him by his wife, Catherine of Aragon, did not survive infancy. Their only surviving child was a daughter, Mary, born in 1516. The Tudors were a new monarchy that emerged out of the chaos of the War of the Roses in the late fifteenth century. Dynastic stability and securing the throne, were central concerns to any kingship. Although medieval England had had powerful royal women, the purview of governance according to ancient and medieval philosophers and theologians belonged to men. For Henry VIII, security of the kingdom was not a theoretical problem, but a serious threat. Henry was not alone in his fear that the Lutheran challenge to the church could result in social, religious, and political disruption leading to violence in England as it had in Germany. Henry’s succession crisis, referred to then and now as the “King’s Great Matter,” became the catalyst for England’s break with the Church.

In 1527, Henry began his petitions to the pope for an annulment of his marriage to Catherine so he could marry a younger woman, Anne Boleyn, in the hope that she would give him the male heir that Catherine could not. By 1529, Henry’s impatience for a papal annulment grew as Rome delayed the king’s petition. Between 1527 and 1541 three important actions moved England toward a national church: the Submission of the Clergy (1532); the Act of Supremacy (1534) which ended papal jurisdiction in England; and the destruction of the monasteries in England which uprooted centuries of monastic culture. By 1535 Henry had created an absolutist monarchy and oversaw a national church. Yet Henry never committed England to Luther’s theological positions and upheld the episcopal church structure and many Catholic theological doctrines.

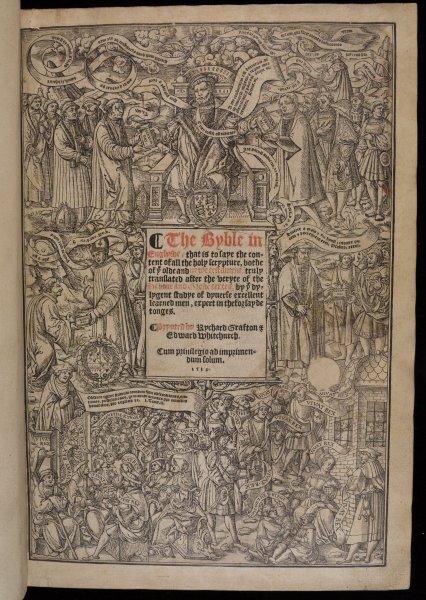

One reformist goal to which Henry did subscribe was to authorize the translation and publication of a bible in English. Until the printing press of the mid-fifteenth century, bibles in the Middle Ages were handwritten often on animal skin parchment (vellum) which was difficult and expensive to produce. Henry’s Great Bible of 1539 and 1540 became the royal authorized editions. The title page image from the Great Bible shows the dissemination of the book to the grateful people of England. Henry commanded that the book be placed prominently in all English churches. Yet not long after this, Henry enacted legislation to restrict its reading. In May 1543, The Act for the Advancement of True Religion forbade the reading of the Bible in English by “women, artificers, apprentices, journeymen, serving-men of the rank of yeoman and under, husbandmen (peasant) and laborers.”

Henry’s was not the last version of the bible in English. By the late sixteenth century new versions had appeared including an authorized Catholic translation, the Douay-Rheims translation of the New Testament (1582). This work, along with other translations, would be used to create what one historian calls the emblem of the English Reformation: the King James Bible of 1611.

Thomas More: A Man for All Seasons or a Man of His Time?

Many authors over four centuries have hoped to capture the true Thomas More and his place in England’s Reformation. The binary of More the humanist and More the persecutor of heretics stymies us. It might be less problematic if we consider the context in which both Mores existed. More was part of an international humanist circle. More, like other humanists, satirized society, politics, the church and its clergy and monks even as he remained steadfast in his commitment to the traditional view of salvation from Christ through the Church, the legitimacy of Christian unity under the pope, and that “outside the Church there is no salvation.”

More’s Utopia and other humanist writings predated the challenge of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses (1517). But the world that More inhabited, that allowed him to produce the Utopia, had changed by the 1520s. In 1521 Pope Leo X excommunicated Luther. Henry VIII authorized his Chancellor and Archbishop Thomas Wolsey to begin a campaign to prevent the Lutheran heresy from spreading in England. In 1524-25 Germany erupted into violence. Henry and Wolsey feared that England would succumb to violence as Germany had. Thomas More was enlisted to counter Lutheran pamphlets in English and engaged in raiding publishers’ warehouses that imported books from Europe. This is the context for More’s turn from the tolerance he wrote of in 1516 in Utopia to the suppression of dissent and heresy that he took seriously.

The Power of Image and Word: Constructing Religious Identity in the English Reformations 1547-1570

Henry VIII’s reforms in the 1530s and 1540s had undercut long-standing religious practices and doctrines such as pilgrimage and the cult of the saints, but it was not entirely divorced from all aspects of the traditional church. Henry viewed the results of his reforms as setting the true church back on course.

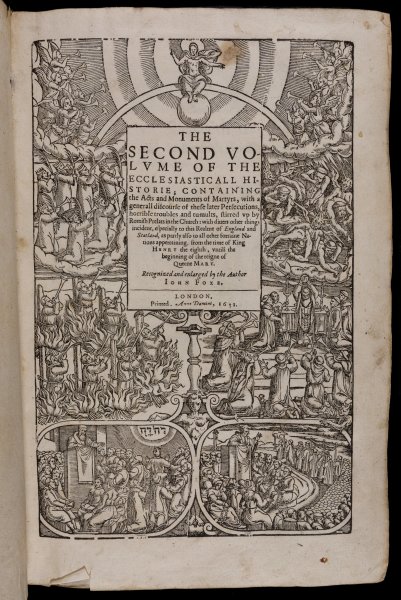

Recent scholarship on the English Reformation has been focused on how the mass of the population who were neither radical reformers nor radical dissenters were turned either toward support for reform or support for the traditional religion. Two ways in which religious identity in the English Reformations was shaped was in the construction of national histories along confessional lines, and in revisions to such texts as the Prymer and Prayerbooks. Printing was not a new technology in the 1540s, but England had far fewer publishing houses than continental Europe. It was one of the most important tools of the Reformation era, as printing helped stimulate a “wider public discussion of evangelical issues” and reinforce religious ideas.

Henry’s legislation in the 1530s and 1540s had overturned 1000 years of Christian practice in less than a 15 year period. The lack of clarity over the new doctrines and rituals caused public confusion. To explain, defend, and especially to denounce resistance to changes in the reform of the English church, Henry’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, utilized the printed word and image to promote and propagandize.

Catholics challenged the Lutherans with the question: “where was your Church before Luther?” The question implied the antiquity of the Roman church tradition against the parvenu status of Protestantism and the origins of Christianity. If England owed its Christianity to missionizing efforts of the papacy, how could they break with Rome? When and how was England converted to Christianity? More importantly, Catholic histories in the sixteenth century argued that the spiritual identity of England predated its political identity.

The four documents here illustrate how English reformers were engaged with the broader religious debates on the continent and built on traditional images to put forth and convince their audiences to a new point of view. They are examples of the use of history and prayer books and show the fine line between propaganda and education.

Emblems of the English Reformations

Alexandra Walsham notes that Catholicism and anti-Catholicism, Protestantism and anti-Protestantism are linked bodies of opinion and practice that “exerted powerful reciprocal influence upon each other.” To understand the internal history of Catholics and Protestants in England one cannot exclude the lateral connections the churches, congregations, and sects had with each other. She describes certain devotional and symbolic objects of the English Protestant and Catholic Reformations that become emblems of faith and religious identity by the late sixteenth-century.

Three important emblems of the English Protestant Reformation are confirmed by several generations of use: the Book of Common Prayer; the Bible in English, and the English hymnal. Although aspects of the Church of England will be challenged by dissenting voices of Puritanism, the Bible, the Book of Common Prayer and the English hymnal will unify the faithful and sustain Protestant religious identity in England into the twentieth century.

For Catholics in England in the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Pope Pius V’s excommunication of Elizabeth in 1570 made a difficult situation worse. In the document, the pope released English Catholics from obedience to Elizabeth whom he declared a heretic. This triggered further proscriptions on Catholics in England and made them a persecuted minority. Walsham points out that the need to practice the faith in secret, to avoid the authorities, and to cope with exclusion from public life paradoxically acted as a catalyst for Catholic religious identity-building. The private Catholic home became a substitute for the ecclesiastical buildings taken over by the Protestants. Reliance on the sacraments (which were outlawed) gave way to the use of “sacramentals,” blessed objects, medallions, scapulars, crucifixes, but especially the rosary. The rosary became an emblem of Catholicism, “the unlearned man’s book,” solitary piety defying institutional control. All these consecrated objects were portable and could be used without the mediation of a priest. They became symbols of a persistent resistance to Protestantism.

Selected Sources

- The Beginnings of English Protestantism. Eds. Peter Marshall and Alec Ryrie. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

- Duffy, Eamon. Reformation Divided: Catholics, Protestants, and the Conversion of England. London, Oxford, New York, New Delhi, Sydney: Bloomsbury Press, 2017.

- Gunther, Karl. Reformation Unbound: Protestant Visions of Reform in England 1529-1559. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2014.

- MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Thomas Cranmer: A Life. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996.

- Heal, Felicity. “Appropriating History: Catholic and Protestant Polemic and the National Past.” Huntingdon Library Quarterly, v. 68, no. 1-2 (March, 2005), 109-132.

- Highley, Christopher. Catholics Writing the Nation in Early Modern Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008.

- Hyatt Mayor, A. “Queen Elizabeth’s Prayers,” The Metropolitan Museum Art Bulletin, N.S. v. 1, no. 8 (April, 1943), 327-242.

- King, John N. Tudor Royal Iconography: Literature and Art in an Age of Religious Crisis. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1989.

- Parish, Helen. Monks, Miracles and Magic: Reformation Representations of the Medieval Church. New York: Routledge, 2005.

- Pettegree, Andrew. “Illustrating the Book: a Protestant Dilemma,” in John Foxe and His World. Eds. Christopher Highley and John N. King. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002, 133-44

- Quantin, Jean-Louis. The Church of England and Christian Antiquity. The Construction of Confessional Identity in the 17th Century. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

- Shagan, Ethan. Popular Politics and the English Reformation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- Walsham, Alexandra. Catholic Reformation in Protestant Britain. Farnham, UK & Burlington, VT: Ashgate Press, 2015.

By Dr. Ann E. Kuzdale

Professor of History

Chicago State University