Readily available lessons from the past point to how Trumpism can be defeated in the present.

By Dr. Dennis Tourish

Professor of Leadership and Organisation Studies

University of Sussex

Abstract

Donald Trump and the movement that he represents pose grave dangers for democracy in America, and throughout the world. I argue that it is now appropriate to describe Trumpism as a form of fascism. The events of January 6th, 2021, when an attempted insurrection sought to prevent the certification of Joe Biden as President, and the agenda that Trump and his supporters are developing for a proposed second term, are viewed as turning points that have transformed Trumpism from populism into an increasingly open form of fascism. I therefore analyse Trump’s rise to power, before discussing the nature of fascism in-depth and considering how Trumpism measures up to the criteria commonly identified as characterising fascism. It also means recognising that without the person of Donald Trump at the helm the MAGA movement will remain a potent threat for the foreseeable future. But it can be defeated. Thus, I identify some of the factors that enabled fascist movements to take state power in the 1920s and 1930s. Its victories were not inevitable then and are not inevitable now. Readily available lessons from the past point to how Trumpism can be defeated in the present.

Introduction

On August 1st 2023 Donald Trump was served with a 45 page indictment on four charges relating to his attempts to overturn the 2020 Presidential election.1 Despite this, or indeed even because of it, he remains at the time of writing the front runner to secure the Republican nomination for the 2024 presidential election. A second Trump term is possible, during which he could, if convicted, pardon himself and return in glory to the White House.2 Like much else about Trump’s political career, this situation is unprecedented. In this paper, I seek to understand what his movement represents. In particular, I consider whether it is appropriate to still regard it as an example of ‘populism,’ or whether a transition towards open fascism has occurred.

This discussion of terminology is not trivial. In order to counteract Trumpism, the threat that it represents must be understood. A threat of this magnitude requires a movement mobilised behind a wide-ranging response. Accordingly, I will discuss the nature of fascism and populism. Resisting the urge to propose an ‘essentialist’ definition, in which some static characteristics are held to be vital for the full phenomenon to be present, I argue that populism and fascism are intertwined. There is always the potential for populism to become fully fledged fascism, and fascist forces have consistently played a significant role in populist movements, including Trumpism.

Insofar as it has traits that distinguish it from right wing populism, fascism is associated with overt and brutal force, the banning of opposition, and the establishment of a one-party state. Populism exploits people’s fears at what are often genuine concerns. Fascism takes this further, to become a violent form of organised despair. I argue that a transition from populism towards fascism within the Republican Party is now at an advanced stage. In particular, the January 6th 2021 attempted insurrection is viewed as a defining movement, when Trumpism assumed an overt fascist position.

In addition, Trump and his aides are planning an agenda for a second term which involves the further gerrymandering of electoral boundaries, a purging of the American civil service to sack anyone who isn’t completely loyal to Trump’s agenda, and the removal of those viewed as unsuitable from electoral rolls. The intention is to instal a semi-permanent Republican presidency dominated by increasingly right-wing extremists. If Trump falls by the wayside, other mini-Trumps would be found to advance his agenda. Instead of what Fukuyama (1992) called ‘the end of history,’ in which the norms of liberal democracy have become an uncontested good throughout the globe, history has been reborn with a vengeance.

I also argue that fascism must be viewed as a process rather than a static phenomenon or a one-off event. A new Trump administration might not be openly fascist from the outset. For example, it could seek to make opposition parties ineffective rather than illegal (e.g. by purging electoral rolls of likely Democrat voters). But a fascist direction of travel would be increasingly evident.

This paper concludes by discussing what can be done to avoid these outcomes. The vengeful, racist and hate filled narratives of Trumpism can only be defeated by narratives that offer better ideas. I argue in favour of what Hodgson (2015, 2021) has described as a reinvigoration of ‘liberal solidarity.’ This involves recognising the harm inflicted on society by neoliberalism, and proposes a comprehensive reimagining of the economy and politics to promote overall wellbeing. But I begin by seeking to explain:

The Rise of Trumpism

Overview

When Trump secured the Republican nomination to run for President in 2016 it was a surprise to many, including perhaps himself. The shock was all the greater when he won the subsequent election. Guthey (2016: 669) aptly expressed it as follows: ‘Trump’s pathology is so astonishingly in-your-face and so unseemly; his addiction to media attention and “winning” so craven; his failures, bankruptcies, and improprieties so well documented, it just seems impossible to many observers that anyone could view him as a plausible candidate for president.’ In addition to his ‘pathology’ it has also long been clear that, intellectually, Trump towers far below most figures in US politics. Adopting Joseph Heller’s description of Major Major in Catch 22, it can be said that some men are born mediocre, some men achieve mediocrity, and some men have mediocrity thrust upon them. With Donald Trump, it has been all three.3 Trump’s skillset is that of a carnival huckster, who finds himself thrust unexpectedly onto the international stage. His subsequent ascent to the summit of US political power represents the triumph of mediocrity. From this pinnacle, he has been able to serve what Laclau (2005a, 2005b) describes as a ‘homogenizing function,’ mobilising an outraged mob behind the revered name of the leader. His ascension surely demolishes the illusion that those who achieve leadership positions must be endowed with talents beyond the norm. How, then to account, for his astonishing political success? I identify five major factors below:

Media Celebrity and the Myth of Trump as a Successful Businessman

Much of Trump’s support was derived from the credibility born from his role as a media celebrity. He presented the ‘reality’ TV show The Apprentice, in one form or another, from 2004 until 2015. There was precious little reality in it. Due to multiple failed investments, Trump’s finances were in freefall until the show came along. It required him to play the part of a successful businessman. This performance earned him an estimated $427.4 million that he then mostly squandered on a new generation of business duds.4 It is somehow fitting that a political career relying on fraud, lies and flimflam has been built on the foundational myth of Donald Trump as a successful businessman.

The Role of Economic Context and Neoliberalism

There is also the important matter of the economic context in which he emerged into the political arena. Nazism owed much of its popularity to the disasters of hyper-inflation in 1923 and the Great Depression in 1929. People became crazed by poverty and uncertainty. Without these stimulants, it is unlikely that Hitler would have triumphed (Gellately, 2020). The situation in the US today is far less severe, but it is nevertheless true that ‘Since 1989, the quality of life for the white working class with no college education had been declining according to almost every measure’ (Walter, 2022: 149). Turchin (2023) shows how, adjusted for inflation, the purchasing power of US workers has declined significantly over the past 30 years, while the wealth of a few has grown stratospherically. People are angry and afraid for a reason. In that sense, statistics for wealth on a global scale (much quoted by Steven Pinker (2018), in his book Enlightenment Now), and which show an overall reduction in world poverty, are misleading. Poverty may have reduced in Africa, India and China, but in key countries like the US the situation is much more complex. Thus, Goethals (2018: 513) has argued that:

‘The populism of Donald Trump and his supporters can be viewed as rooted in feelings of relative deprivation, whereby people feel that they are getting less than they deserve in exchanges with other groups, and perceptions of unfair procedures, whereby elites are seen to allocate outcomes in an unethical, biased, and/or disrespectful manner.’

There are few cries more raucous, and familiar, than ‘It’s not fair.’ Applebaum (2020) argues that when people feel they have lost out in society, compared to their rivals or peers, they are more likely to revolt against the perceived tyranny, inequities and injustices of ‘the system.’ Studies show that the less prosperous people feel themselves to be, then the more likely it is that they will be attracted to authoritarianism and populism (Norris and Inglehart, 2019). Economic calamity enables populist and fascist leaders to promote a narrative of crisis, and to arouse fears that they then promise to ease. Spector (2019) has argued that Trump made a claim of crisis – ‘American carnage’ – to support his ambition to be taken as the one person who could solve that carnage. It appears that many were only too willing to be convinced.5

In my view, addressing this necessitates an engagement with the legacy of neoliberalism. Put briefly, this has elevated shareholder value as the ultimate and indeed often only purpose of corporate activity. Neoliberalism has been described as ‘the ideology of perfect and undistorted competition’ (Stiegler, 2015: 124) that strives to ‘economise every sphere and human endeavour’ (Brown, 2018: 62). The consequences have been severe. I offer here just one example – that of General Electric. Under Jack Welch it cut hundreds of thousands of jobs and moved them offshore to boost profits and shareholder value. Whole communities were devastated. Welch’s successor, Jeff Immelt, who served as GE’s CEO from 2001 to 2017, blandly reflected on all this as follows: ‘We lived in the world’s biggest markets. If we could do things more productively by moving work offshore, why not? As capitalists, we thought this was our right; we didn’t think much about the consequences’ (Immelt, 2021: 177). Laid off workers certainly thought of the consequences, and the anger and desperation of many of them found paradoxical expression in support of a self-proclaimed billionaire whose inaugural presidential address promised retribution and renewal:

‘For too long, a small group in our nation’s Capital has reaped the rewards of government while the people have borne the cost. Washington flourished – but the people did not share in its wealth. Politicians prospered – but the jobs left, and the factories closed. The establishment protected itself, but not the citizens of our country. Their victories have not been your victories; their triumphs have not been your triumphs; and while they celebrated in our nation’s capital, there was little to celebrate for struggling families all across our land… We are transferring power from Washington, DC and giving it back to you, the American people… The forgotten men and women of our country will be forgotten no longer.’6

Of course, Trumpism has deep roots in Republican Party history. Much of it resembles McCarthyism in the 1950s, Barry Goldwater’s 1964 rhetoric that defended what he called ‘extremism in defense of liberty,’ Richard Nixon’s Southern strategy in the late 1960s (which involved appealing to white voters through racist dog whistles that often became bullhorns), and Ronald Reagan’s influential attacks on the very idea of government. (Reagan famously used his 1981 inaugural address to declare that ‘Government isn’t the solution to the problem: government is the problem’). But the economic context discussed above is crucial to the current revitalisation of such thinking. Trump himself is both a cause and symptom of the MAGA movement. He has the demagogue’s age-old ability to identify scapegoats who could be blamed for all manner of problems, and a limited vocabulary which needs only to howl with contagious rage. What he lacks in eloquence he makes up for with malign invective. In 2016 and since, it requires no great ability to know what scapegoats would resonate with an already radicalised Republican constituency, and even less to road test a handful of memorable slogans (e.g., MAGA) through endless rallies that would further fuel the fires of fury.

Trump as Ethnic Entrepreneur

But the rise of Trumpism isn’t just about economics. In considering fascism past or present we need to resist the allure of monocausal explanations. Laqueur (1996) points out, for example, that other countries besides Germany were severely impacted by the Great Depression of 1929, some more so, but their fascist movements remained insignificant. What else drove the rise of Trumpism in the United States?

Barrack Obama’s Presidency saw a black man in the White House for the first time in history. This inflamed racist feelings on the Republican right, which argued that he was an illegitimate president and not really American. Levitsky and Ziblatt’s (2018: 159) cite the Tea Party activist and radio host Laurie Roth as follows: ‘This was not a shift to the Left like Jimmy Carter or Bill Clinton. This is a worldview clash. We are seeing a worldview clash in our White House. A man who is a closet secular-type Muslim, but he’s still a Muslim. We are seeing a man who is a Socialist Communist in the White House, pretending to be an American.’

This is politics as deranged fantasy. Experts on civil wars have coined the term ‘ethnic entrepreneurs,’ to describe those who exploit racial tensions for their own interests (Walter, 2022). Trump has become precisely such an individual. In doing so, he was able to draw from a deep well of racism in America. Thus, he championed the absurd idea that Obama hadn’t been born in America, thereby disqualifying him from the Presidency. When his birth certificate was released in 2011, proving otherwise, Trump argued that it was a forgery. Consider also his infamous description of Mexican immigrants coming to the United States:

‘When Mexico sends its people, they’re not sending their best. They’re not sending you. They’re not sending you. They’re sending people that have lots of problems and they are bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.’7

This statement was delivered in June 2015, during his announcement that he was running for President, and evidently did him no harm at all. It is an outstanding example of what Korestelina (2017) calls ‘identity insults,’ used to demonise designated outgroups while assuring the ingroup, his supporters, of their superiority. The racist intent is unmistakeable. Harcourt (2018) argues forcefully:

‘Trump knows exactly what he is doing – as he does when he disparages “globalists” or Soros, mocks “political correctness,” or uses demeaning and dehumanizing expressions such as “infest,” “animals,” “rapists,” and “shithole” countries to describe immigrants and African nations. These are deliberate fodder for his white nationalist base.’

Not coincidentally, militia movements have grown significantly in the years since Obama’s election. A report published in 2020 by The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project 2020, (ACLED) identified at least 80 militia groups in the US, overwhelmingly right wing. White supremacism has penetrated the Republican Party from top to bottom. In Anderson’s (2022: 904) words, ‘Shockingly, Trumpism can be seen as further to the right even when one compares it not to main-stream conservatives but to far-right parties in Europe.’ Marche (2022) concluded that: ‘The white supremacists in the United States are not a marginal force; they are inside its institutions.’

It is revealing that such movements have been deeply influenced by William Pierce’s novel The Turner Diaries. The novel describes a post-apocalyptic America in which society has been purified through a race war. One chilling passage illuminates this bloodthirsty vision and the nature of the final solution it envisages. The diary’s putative chronicler describes walking the streets to see bodies hanging from every lamppost, sometimes ‘four at every intersection.’ He describes seeing a woman dangling from a tree and wearing a placard on which is scrawled ‘I defiled my race.’ Among those influenced by this text was Timothy McVeigh, one of the two architects of the Oklahoma bombing in 1995 in which 168 people were killed. Nineteen of these were children. The intent was to provoke a race war in America, and indeed initial speculation assumed that the bombing was the work of Islamic terrorists (Tourish and Wohlforth, 2000; Wilentz, 2023). When arrested, McVeigh had photocopied portions of The Turner Diaries in his possession. It continues to circulate among militia movements and white supremacists to this day.

The resultant mindsets lead Turchin (2023: 211) to issue the alarming warning that ‘the Republicans are making a transition to becoming a true revolutionary party.’ This is unprecedented. It poses a far greater risk to democracy and stability than possibly any other period in modern American history. Goethals (2021: 248) put it in these terms: ‘There is still such a thing as a moderate Republican, but the breed is nearly extinct. The party is headed further and further to the right. As it does, its anti-democratic tendencies will become more prominent.’

We are now in a world of dangerous firsts. Walter (2022: 146), a world expert on civil wars, points out that ‘No Republican President in the past 50 years had ever pursued such an openly racist platform, or championed white, evangelical Americans at the expense of everyone else.’ Snyder (2018: 274) lists other firsts:

‘Trump was the first presidential candidate to say that he would reject the vote tally if he did not win the election, the first in more than a hundred years to urge his followers to physically beat his opponent, the first to suggest (twice) that his opponent should be murdered, the first to suggest as a major campaign theme that his opponent should be imprisoned, and the first to communicate internet memes from fascists. As president, he expressed his admiration for dictators around the world.’

Media Fragmentation, Echo Chambers, and the Hunger for Charismatic Leadership

Trump’s ascendancy can also be partly explained by media fragmentation. Klein (2020) cited a revealing study in 2014. It found that those who were consistent liberals accessed a wide a variety of media sources, ranging from centre right to the left. But those who identified as consistent conservatives relied overwhelmingly on a small handful of highly ideological media outlets, such as Fox News, Breitbart, The Sean Hannity Show and The Rush Limbaugh Show. 47% had Fox News as their preferred source. Social media, an echo chamber par excellence, amplifies this effect.

The sense of absolute conviction that is then developed, combined with intense identification with a leader (a puzzle to many who have been baffled by the hold that Trump has over his followers) is strongly reminiscent of organizations that are generally defined as cults (Hassan, 2019). In line with this, Chace (2021: 365) described Trump’s leadership in the run up to the 2020 election as ‘darkly charismatic, authoritarian, and cultish.’ Mason (2021: 44) cites a 1930s historian, Lucie Varga, on the similarities between fascist identification and religious conversion, which certainly seems to describe the cultic dynamics within much of the MAGA movement:

‘a group of people in dynamic despair, for whom life in the old framework, according to the old scale of values, has lost all meaning. At the bottom of the despair and solitude lies the illusion of a golden age and the nostalgia of a paradise lost. (Then come) the first meetings, the key to a discovered world: the gift of yourself, giving oneself over to the new doctrines which prepare those persuaded to reject any other logic, symbol, myth or holy book.’

I argue that this owes little to any imagined charisma on Trump’s part, but a great deal to the social situations in which his followers find themselves – a social media echo chamber, membership of an exciting and revolutionary movement, and the possession of simple answers (MAGA) to complex problems. Followers and leaders collude in the social construction of a charismatic persona that is vital for ‘Strongmen’ leaders of all types (Eatwell, 2018). It is a self-reinforcing cycle, since people enthralled by populist leaders grow hungrier for charismatic leadership and ever more dependent on the revered leader (Metz and Plesz, 2023).

Trump Rallies and the Power of In-Group Identification

Lastly, despite the importance of social media, particularly Trump’s use of Twitter, mass events remain critical. Drawing on the ideas of Freud and Lebon, Goethals (2021: 242) discusses

‘the relief from restraint that people experience in crowds (and) the lifting of inhibitions and the expression of often ugly passions resulting from feelings of anonymity and power that one feels in a crowd. People feel intensely bonded both to each other and to the leader. The group’s common identification with the leader welds them to each other and enables the leader to take them nearly anywhere he wants them to go.’

Trump rallies are joyful celebrations of fraternity and certainty. They insulate participants from external criticisms or doubt (French, 2023). Supporting this, Reicher and Haslam (2017: 45) offer the following illuminating analysis of a Trump rally:

‘A rally would start long before Trump’s arrival. Indeed, the long wait for the leader was part and parcel of the performance. This staged delay affected the self-perception of the audience members (“If I am prepared to wait this long, this event and this leader must be important to me”). It affected the ways audience members saw one another (“If others are prepared to wait this long, this event and the leader must be important to them”). And it thereby set up a norm of devotion in the crowd and a sense of shared identity among crowd members (“We are joined together in our devotion to this movement”).’

It is also worth noting Arendt’s (1951) point, in her influential book The Origins of Totalitarianism, that loyalty to an individual great leader is a key characteristic of totalitarian movements – both communist and fascist. The devotion of the MAGA movement to Trump certainly exceeds anything found in normal politics. As he himself famously declared during his first Presidential run: ‘I could stand in the middle of Fifth Avenue and shoot somebody, and I wouldn’t lose any voters.’8 Blind faith of this kind may be helpful to authoritarian leaders and would be dictators, but it is clearly incompatible with rational thought. There is no better illustration of this than:

The Centrality of Conspiracy Theories to Trumpism

Arendt (1951: 474) wrote that ‘The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (i.e., the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (i.e., the standards of thought) no longer exists.’ People become entitled to their own set of ‘alternative facts.’ A given theory explains everything, to the complete satisfaction of those who have become its ecstatic converts.

Conspiracy theories perform precisely this role, and it is therefore unsurprising that they have always been a central feature of fascist movements (Uscinski, 2019). They create what Gabriel (2016, 2021) describes as distinctive ‘narrative ecologies,’ in which leaders target scapegoats held to be responsible for society’s problems and pose as the only force capable of overcoming them. Notoriously, the Nazis made extensive use of The Protocols of The Elders of Zion, a forgery probably written around 1902 and drawn from several sources, which purported to detail a Jewish plot to take over the world. Writing in Mein Kampf, Hitler dismissed claims that the Protocols were forged as ‘the best proof that they are authentic … the important thing is that with positively terrifying certainty they reveal the nature and activity of the Jewish people and expose their inner contexts as well as their ultimate final aims.’9 It is typical of conspiracy theories that the absence of evidence, or the presence of counter evidence, is taken as further proof that the conspiracy is real. It has simply become adept at concealing its existence. The result is what Robins and Post (1997: 37) describe as a paranoid style of politics, whose participants:

‘believe that a vast and subtle conspiracy exists to destroy their entire way of life. What is notable about the paranoid’s view of history is not that he believes conspiracies exist and are important – after all, they do exist and may be important – but that he sees conspiracy as the motivating force in history and the essential organizing principle in all politics. Characteristically, the conspiracy is described as already powerful and growing rapidly. Time is short. Absolute and irreversible victory of the conspiratorial group is near. The few people who recognize the danger must expose and fight the conspirators. The conflict cannot be compromised or mediated. It is a fight to the death. The conspirators are absolutely evil, and so, as the opponents of this evil power, members of the paranoid groups see themselves as the force for good. Indeed, they acquire in their own eyes the role of the defenders of all that is good. The struggle is cast in Manichaean terms as between good and evil.’

One of the best-known conspiracy theories within the MAGA movement is QAnon, which claims that Barrack Obama is a Muslim sleeper agent, and that Hillary Clinton is part of a Satanic global paedophile sex trafficking ring which ritualistically murders children (Rothschild, 2021). As part of ‘the Deep State,’ so the story goes, this ring has been running the US for years and has been involved in countless attempts to assassinate Donald Trump, who alone can defeat it. Trump, in turn, has reposted QAnon messages on social media, signalling at least some endorsement of its insane and evidence free claims.10 Two supporters of the theory, Marjorie Taylor Greene and Lauren Boebert, serve in Congress. Many of those who participated in the January 6th insurrection wore QAnon insignia – tee-shirts, flags and signs with Q slogans (Mogelson (2022).

What is known as ‘The Great Replacement Theory’ has also gained wide popularity within the MAGA movement. This argues that ‘white European populations are being deliberately replaced at an ethnic and cultural level through migration and the growth of minority communities’ (Davey and Ebner, 2019: 7). The theory has been promoted on Fox News by Tucker Carlson, who argued that Democrats were seeking to ‘replace the current electorate’ with ‘more obedient voters from the Third World.’ There have been lethal consequences. In August 2017, a ‘Unite the Right’ rally was held in Charlottesville. Marchers chanted ‘You will not replace us!’, and then ‘Jews will not replace us!’ (Neiwert, 2023: 26). A right-wing activist rammed his car into counter protesters. One person died and 19 others were injured. Mass killings at least partly inspired by the theory have taken place in Christchurch, New Zealand; Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; and El Paso, Texas. Neiwert (2023) reports the results of a 2022 survey of 1500 people which found that 70% of Republican voters believed in the theory.

Even more believe in the greatest conspiracy theory of them all – that the 2020 election was stolen from Trump by the Democrats. This would have required ‘a gigantic conspiracy involving thousands of people, none of whom seems to have blabbed to their families, friends, neighbours or media about what they had done’ (Tourish, 2023: 350). Booted out by innumerable courts, and lacking even a scintilla of evidence in its favour, the theory thrives in the twilight zone of paranoid conspiracy. At this stage, few of its adherents would be surprised if Trump announced that he has in fact won every Presidential election since 1789, only to be thwarted by ballot rigging Democrats.

Yet there is also something particularly alarming here. Muirhead and Rosenblum (2019: 3) draw attention to the following distinctive characteristic of conspiracy theories within the MAGA movement:

‘There is no punctilious demand for proofs, no exhausting amassing of evidence, no dots revealed to form a pattern, no close examination of the operators plotting in the shadows. The new conspiracism dispenses with the burden of explanation. Instead, we have innuendo and verbal gesture: “A lot of people are saying…” Or we have bare assertion: “Rigged! – a one-word exclamation that evokes fantastic schemes, sinister motives and the awesome capacity to mobilize three million illegal voters to support Hillary Clinton for president. This is conspiracy theory without the theory.’

It is startling to reflect that neither Trump nor any of his acolytes have produced the slightest shred of evidence in support of their Big Lie about the 2020 election. As things stand, there is more evidence in favour of alien life on Mars than there is that the election was rigged. But all this poses the following question:

What Is Fascism Anyway?

Overview

Often, ‘fascist’ has been little more than a word of abuse for multiple things that we dislike. This has been true throughout its history. George Orwell noted in 1946 that ‘The word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies “something not desirable.”’ He went on to ridicule those who used this vagueness to argue that ‘Since you don’t know what Fascism is, how can you struggle against Fascism?’

The term has its origins in Italy, where Mussolini used the word ‘fascismo’ after World War 1, to describe those gathered around him. It has been subsequently applied to Nazi Germany, and Franco’s rule in Spain, although each of these regimes had distinctive characteristics. For example, fascist propaganda in Spain emphasised Catholicism to a far greater extent than other European fascist movements and sought to embed Catholic ideology in all manner of institutions (Payne, 1999). For that matter, Italian fascism displayed limited signs of anti-Semitism until it had been in power for 16 years, while Mussolini himself at one point had a Jewish mistress (Paxton, 2004). In Germany, meanwhile, genocidal insanity became Government policy. The Nazi regime was also much more totalitarian than its Italian counterpart, vicious as that was (Eatwell, 2017). What bound these disparate movements together, and how can we identify fascism in the 21st century?

There is no one agreed definition of fascism (Griffin, 1991). However, scholars generally cohere around a number of distinguishing traits. In particular, Paxton (2004: 209–210) identifies what he describes as nine ‘mobilising passions’ of fascism. These are:

• ‘A sense of overwhelming crisis beyond the reach of any traditional solutions;

• The primacy of the group, toward which one has duties superior to every right, whether individual or universal, and the subordination of the individual to it;

• The belief that one’s group is a victim, a sentiment that justifies any action, without legal or moral limits, against its enemies, both internal and external;

• Dread of the group’s decline under the corrosive effects of individualistic liberalism, class conflict, and alien influences;

• The need for closer integration of a purer community, by consent if possible, or by exclusionary violence if necessary;

• The need for authority by natural chiefs (always male), culminating in a national chieftain who alone is capable of incarnating the group’s historical destiny;

• The superiority of the leader’s instincts over abstract and universal reason;

• The beauty of violence and efficacy of will, when they are devoted to the group’s success;

• The right of the chosen people to dominate others without restraint from any kind of human or divine law, right being decided by the sole criterion of the group’s prowess within a Darwinian struggle.’

Fascist movements are usually helmed by a supreme leader, said to ‘intuitively’ understand the people and its historic destiny (Prowe, 1994). These leaders habitually pose as champions of the people, opposed to a corrupt elite. The leader promises to do away with this elite, and unite the nation around a crusade against hated enemies and behind a project of national renewal (Eatwell, 2017). This requires a narrative of chaos and an intense effort to persuade by arousing fear of the present and hatred of outgroups. Much of this seems very like an indictment of Trump’s role in American politics over recent years.

At the ideological core of fascism is a form of paranoid and narcissistic nationalism (Stanley, 2018; Finchelstein, 2022). Groups are defined in terms of the nation, with the often overt suggestion that this particular nation (Germany/Italy/America) is superior to all others. But its superiority is endangered by various internal outgroups (e.g., Jews, ethnic minorities, liberals) who are said to be imperilling the unity and vitality of the nation. They are traitors, who should be deprived of normal civic rights, and in extremis denied the right to life. This is not normal democratic politics, where rivals compete fiercely with each other but don’t see electoral defeat as presaging the end of the world as we know it. Democratic parties rely on the electoral process to change outcomes that they don’t like.

Exploiting grievances, real or imaginary, fascism in my view can be regarded as a form of organised despair. Emotion takes precedence over thought (Langman and Lundsknow, 2022). As such, ‘the role programs and doctrine play in (fascism) is… fundamentally unlike the role they play in conservatism, liberalism, and socialism. Fascism does not rest explicitly upon an elaborated philosophical system, but rather upon popular feelings about master races, their unjust lot, and their rightful predominance over inferior peoples’ (Paxton, 2004: 16). Whites are pitted against blacks; Americans against Mexicans; Gentiles against Jews; and, Christians against Muslims, all deemed to pose an existential threat.

Fascism actually has a long and inglorious history in the United States (Rosenfeld and Ward, 2023). It is not an alien tradition, inconceivable within its borders. The infamous Father Coughlin urged support for Mussolini and Hitler because of their opposition to Communism. His radio broadcasts during the 1930s had audiences in the tens of millions. Coughlin argued that Jewish bankers were behind the Russian Revolution, and his magazine serialised publication of The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. In the early 1920s, the car manufacturer Henry Ford endorsed them in a four-volume series entitled The International Jew: The World’s Problem.

Such propaganda had a considerable impact. Polls conducted in the late 1930s suggested that ‘at least 50% of Americans had a ‘low opinion’ of the Jews’ (Gordon, 2023: 160). 54% thought at least some of the Nazi oppression was the Jews’ own fault, while in 1939 10% agreed that they should be ‘humanely’ deported. These sentiments took on a physical form. In February 1939 the German American Bund organised a rally in Madison Square Garden, New York, that attracted 20,000 people (Kramer, 2019).11 The venue was draped with both American flags and swastikas. Many attendees wore Nazi armbands, and the aisles were patrolled by men dressed as stormtroopers. At frequent intervals, the audience enthusiastically displayed the Nazi salute.

Fascism Rebranded as Populism

The defeats of fascism in World War Two, and the exposure of Nazi barbarism in the Holocaust, necessitated a rebrand. Fascism in this century was never likely to assume an identical form to that of Germany, Spain or Italy in the 1930s (Todorov et al., 2003). As the great Italian novelist Umberto Eco wrote in 1995: ‘It would be so much easier, for us, if there appeared on the world scene somebody saying, “I want to reopen Auschwitz, I want the Black Shirts to parade again in the Italian squares.” Life is not that simple.’ Fascism is a highly protean phenomenon, and as Eco went on to point out, this means that it ‘can come back under the most innocent of disguises.’ Neiwert (2023: 13) concluded that ‘an American form of fascism would manifest itself in its own distinct way: swaddled in red, white, and blue bunting, demanding fidelity to “Christian” principles, and pronouncing its innately seditious politics as “patriotism.”’ Fascism can exist without jackboots, blackshirts and a toothbrush moustache. But for all the permutations fascist inclined movements have gone through in the post war period, leading to the adoption of such labels as ‘populism,’ ‘neofascism’ and even ‘fascism light,’ they overwhelmingly retain an affinity for the racist, nationalistic, totalitarian and violent archetypes of their pre-war incarnations (Copsey, 2018). Fascism may have changed its colours from time to time, and identified new enemies as the need arose. What it has never done is disappear. Thus, while populism has varied historical antecedents, and has taken both left- and right-wing forms, it has since the mid-twentieth century ‘been a far more potent force on the right’ (Lowndes, 2017: 233). It this incarnation, and its roots in fascism, with which I am concerned.

In line with this, Finchelstein (2017: xxiv) differentiates between populism and fascism as follows:

‘By 1945, populism had come to represent a continuation of fascism but also a renunciation of some of its defining dictatorial dimensions. Fascism put forward a violent totalitarian order that led to radical forms of political violence and genocide. In contrast, and as a result of the defeat of fascism, populism attempted to reform and retune the fascist legacy to a democratic key. After the war, populism was an outcome of the civilizational effect of fascism.’

This views populism as fascism light – a decaffeinated version of the original, the search for respectability compels the at least nominal acceptance of democratic norms and the pursuit of power through elections rather than putsches. Nevertheless, Levitsky and Ziblatt’s (2018: 22) influential study of How Democracies Die notes that populist leaders:

‘… tend to deny the legitimacy of established parties, denouncing them as undemocratic and even unpatriotic. They tell voters that the existing system is not really a democracy but instead has been hijacked, corrupted or rigged by the elite. And they promise to bury that elite and return power to “the people.”’

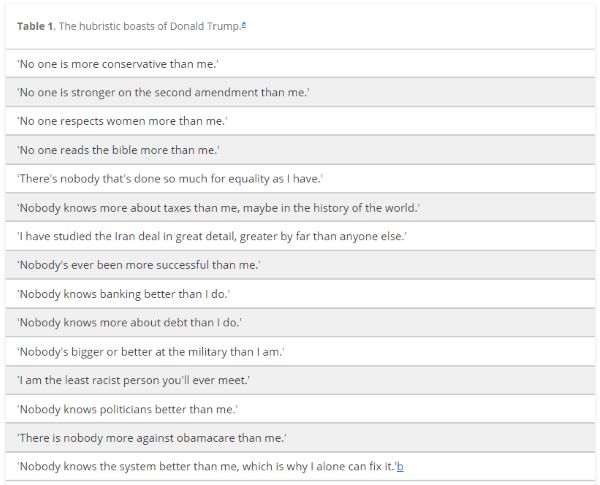

Like fascism, populism is generally associated with a particular leader, projected as a Strongman (literally – almost all populist leaders in the world today are men) who is uniquely qualified to heal society’s wounds (Mudde, 2004; Moffitt, 2016; Ben-Ghiat, 2020). This is one of its outstanding points of similarity with fascism (Eatwell, 2017), and is characteristic of Trump’s own pronouncements He often depicts himself as a ‘superhero’ (Schneiker, 2020). Table 1 lists just some of his boasts which show case this mentality.

Despite these statements, and in comments that defy parody, he has said: ‘I do actually have much more humility than a lot of people would think,’12 while also asserting that he was ‘a very stable genius.’13

It is important to recognise that the dividing line between populism and fascism has always been fluid. Finchelstein (2017: 93) identifies a key difference as follows: ‘Unlike fascism, populism does not fully marginalise the “enemies of the people” from the political process. Rather, its leaders and followers want to defeat their candidates with formal democratic procedures. Elections and not elimination are key sources of legitimacy in populism.’ But Finchelstein (2017: 186) goes on to offer a caveat: ‘The moment that the populist leader ignores democratic procedures, populism betrays its renunciation of dictatorship and becomes one… When the leader does not acknowledge the possibility of stepping aside when faced with conditional limits, populism is unravelling and, in a sense, stops being populist.’ More bluntly: it becomes fascism. Fascism became populism after 1945, and populism can once again become fascism in our century. We therefore need to ask:

Is Trumpism Fascism?

Overview

The well-known UK journalist, Paul Mason, published an influential book in 2021 entitled How to Stop Fascism. In it, he writes: ‘Let’s state what should be obvious: Trump is not a fascist’ (p 39). He based this assessment on Trump’s record as President, where by and large democratic norms prevailed. But he also acknowledged that ‘both Trump himself, and his movement, are a work in progress’ (p. 40). The eminent historian Richard Evans reached a similar conclusion in 2021, mainly on the basis that Trump showed no desire to fight wars against foreign powers, unlike fascism in the past.14 I argue here that these conclusions have been overtaken by events. Holding first place in the case for the prosecution is, of course, the events of January 6th, 2021, when a mob inspired by Trump attempted to stop the certification of Biden’s win in the preceding election. In second place are the plans that have been declared for a Trump second term, should it come to pass. Trump and his party have now decisively rejected democracy, and are seeking to ensure that the only elections which will be held in the future are those that they are guaranteed to win.

The Significance of January 6th

It is difficult to overstate the importance of this date. It was the culmination of multiple attempts by Trump and his team to overturn the election. Trump apparently considered using the Insurrection Act, which would have meant declaring a state of national emergency and authorising the military to seize voting machines and ballot boxes. Part of the pretext was to be concern that China had gained control over the electoral process (Mogelson, 2022). But, more importantly, it rested on the presumption that antifascists (dubbed Antifa) would turn out on force on January 6th, thereby enabling Trump to depict them as the real insurrectionists. When they stayed away, the plot fell apart, with only one bizarre coda, naturally amplified on Fox News. This was the suggestion that those who invaded the Capitol were really Antifa activists, seeking to discredit the MAGA movement.

On the day itself, 180 police officers were wounded. One lost an eye. Another was stabbed with a metal fence stake. Protesters chanted such peaceful slogans as ‘Hang Mike Pence’; ‘Kill the traitors’; ‘Hang the traitors’; ‘Get those fucking cocksucking commies out’; ‘Victory or death.’ One protester was shot dead, and four others died in stampedes or of heart attacks and strokes. A policeman attacked by the mob died and two others later committed suicide.

It was unprecedented for a defeated candidate to encourage such violence or refuse to participate in a peaceful transfer of power. Neiwert (2023) suggests that the long delay in the National Guard showing up to protect members of Congress rested on the hope by Trump that enough people would be killed to prevent the certification process. Mogelson (2022: 6) goes further still. He argues that ‘the insurrection’s attempt was to overthrow democracy itself and replace it with an authoritarian autocracy. The intended outcome was to install Trump as the nation’s permanent president for life: a dictator in the mold of Russia’s Vladimir Putin, Hungary’s Vickor Orban, or Turkey’s Recep Tayip Erdogan.’ At one point during these events Trump tweeted ‘Mike Pence didn’t have the courage to do what should have been done to protect our country and our Constitution.’ O’Toole (2023) argues, I think convincingly, that this was at the very least ‘implicitly providing a mandate for murder.’

A refusal to accept legitimate election results, and the incitement of violence against political opponents, are of course classic ingredients of fascism. It moved Robert Paxton (2021), a leading expert on fascism, to declare that: ‘Trump’s incitement of the invasion of the Capitol on January 6, 2021 removes my objection to the fascist label. His open encouragement of civic violence to overturn an election crosses a red line. The label now seems not just acceptable but necessary.’ Trumpism is only prepared to accept election results that are in its favour. Trump himself is no longer alone in this. When Kari Lake lost her campaign for the governorship of Arizona in 2022, she immediately claimed that the election had been rigged.15 At the time of writing, she is among the leading contenders to be named by Trump as his running mate, should be secure the Republican Party nomination for 2024.16 These developments have led Ben-Ghiat (2023: 400), a leading expert on authoritarian leaders, to conclude that ‘Trump can be called a fascist because he differed from any previous American president in having the explicit goal of destroying democracy at home, disengaging America from democratic international networks, and allying with the autocrats he admires, like Putin.’ When we look ahead, this verdict only gathers strength.

Plans for a Second Term

A Trump second term, if it comes to pass, will be better prepared, and more autocratic, than his first. Plans are afoot to bring agencies such as the Federal Communications Commission – responsible for enforcing rules on television and internet companies – under direct presidential control. Employment protections from career civil servants would be removed, opening the way to the dismissal of all those from intelligence agencies, the State Department and defence bureaucracies deemed insufficiently loyal to Trump (Swan et al., 2023). The Economist reports that expressing any doubts about what happened on January 6th will be grounds for dismissal.17 Culture wars would proliferate. Trump has promised to create a presidential commission that would promote a ‘patriotic’ curriculum in schools that would, among other things, eliminate scholarship on systematic racism (Arnsdorf and Stein, 2023).

Linked to this, more attempts are being made to promote what is known as voter suppression. Some state Republican officials

‘have rewritten statutes to seize partisan control of decisions about which ballots to count and which to discard, which results to certify and which to reject. They are driving out or stripping power from election officials who refused to go along with the plot last November, aiming to replace them with exponents of the Big Lie. They are fine-tuning a legal argument that purports to allow state legislators to override the choice of the voters’ (Gellman, 2022).

As one example, an elected Republican in Arizona has proposed that the state legislature should have the power to overturn the results of presidential elections (Klass, 2023). The Brennan Centre for Justice reported in 2021 that over 425 bills had been passed aiming to restrict voting in 49 states. These include placing limits on mail-in voting, tougher voter ID laws, and the purging of voter rolls. Black voters, long subject to voting restrictions and suspected of being more likely to vote Democrat, are especially susceptible (Chen et al., 2020; Nieman, 2020).

Gerrymandering is also becoming more common – that is, the manipulation of electoral boundaries to favour a minority over the majority. For example, Nashville had a single Democrat representing it in Congress. However, the electoral map was redrawn before the 2022 elections to split it into three districts. Each went on to elect a Republican (Applebaum, 2023). Essentially, the MAGA movement is planning to sack the electorate, and replace it with one more to its liking. If there is any ‘Great Replacement’ underway it is this. Gellman (2022) outlined the implications of these developments as follows:

‘Technically, the next attempt to overthrow a national election may not qualify as a coup. It will rely on subversion more than violence, although each will have its place. If the plot succeeds, the ballots cast by American voters will not decide the presidency in 2024. Thousands of votes will be thrown away, or millions, to produce the required effect. The winner will be declared the loser. The loser will be certified president-elect.’

Future Transitions of Power, and the Possibility of Civil War

What are the implications for future transitions of power, should Trump indeed win a second term? Heather Cox Robinson, a history professor at Boston College, has no doubts: ‘The signs are all there that he would not leave voluntarily… After all, he did his best to stay in office in 2021, sparking an insurrection to do it, and he has vowed to use the power of the presidency more forcefully in a possible second term.’18 I see no reason to disagree. This danger goes beyond Trump. Even if he himself is no longer around (his one virtue is that he is mortal), it seems probable that those who have branded themselves with his image would still follow the trail that he has pioneered. America would be on its way to becoming what experts call an ‘anocracy’ – that is, neither fully democratic nor fully authoritarian, but somewhere between the two. It is in such spaces that civil wars most often develop (Walter, 2022).

As the party moves ever more to the right, some Republicans are indeed now openly advocating a civil war. A survey conducted in 2021 found 56% of Republicans agreeing with the view that ‘the traditional American way of life is disappearing so fast that we may have to use force to save it’ (cited in Levtsky and Ziblatt, 2023: 120). People such as Steve Bannon, a former key aide to Trump, have been more than willing to exploit this mood. Consider his words during a speech to thousands of MAGA activists in December 2022:

‘Are we at war?” he demanded to know at the outset.

After a feeble “Yes” from the audience, he repeated: “No! I wanna hear it! Are we at war?” “Yes!!!” the audience shouted.

“Are you prepared to take this to its ultimate conclusion and destroy the Deep State?” he demanded. “Yes!!!!” they replied. “Root and branch?”

“Yeahhh!!!”

“This is what they fear,” Bannon continued. “They fear not just an electorate that is informed, but an electorate that says, “No longer are we just going to sit there and take it!”

‘You are an awakened army!” he bellowed. The crowd cheered’ (Neiwert, 2023: 447).

Such a war needn’t take the conventional form of standing armies on a battlefield. Rather, it would be protracted, episodic and intermittently violent in nature – perhaps more akin to the nearly 30 years of violence that disfigured Northern Ireland up until the Good Friday Agreement of 1998 (Walter, 2022). For example, the ready availability of guns in America enables what has been called ‘lone wolf terrorism,’ whereby isolated individuals who have been radicalised online or in social groups go on to commit mass shootings and bombings (Hamm and Spaaij, 2017). There may yet be many who are willing to follow the example of Timothy McVeigh.

I also argue that fascism must be viewed as process rather than a static phenomenon or a one-off event. A new Trump administration might not begin as a fully-fledged fascist regime, although this is a possibility.19 Blown hither and thither by events, including the possibility of mass opposition, any pretence of respect for the norms of democracy would likely have a lifespan shorter than that of a fruit fly. Even if opposition parties are not formally banned, at least initially, voter suppression and the ever more blatant gerrymandering of electoral boundaries would seek to ensure that they become ineffective. If this proves insufficient the Great Replacement Theory surely provides a convenient rationale for openly restricting the franchise to those who can be deemed ‘True Americans.’ Dissenters would be branded as ‘traitors,’ eventually leading to restrictions on freedom of speech and demands that those derided as traitors be put on trial. Chants of ‘lock her up’ at Trump rallies when Hillary Clinton stood against him in 2016 offer a foretaste of how this might develop. However, none of this is inevitable. Which leads to the million-dollar question:

How Can Trumpism Be Defeated?

Overview

My starting point is to warn against a sense of inevitability when viewing fascism’s past, or fatalism when considering its future. Kershaw (1998: 424–425) argued as follows in his biography of Hitler: ‘There was no inevitability about Hitler’s accession to power… Democracy was surrendered without a fight.’ In words that could be written for today, he noted that ‘A few took (Hitler) at his word, and thought he was dangerous. But far, far more, from Right to Left of the political spectrum – conservatives, liberals, socialists, communists – underrated his intentions and unscrupulous power instincts at the same time as they scorned his abilities’ (Kershaw, 1998: 424). Thus did his opponents become the invincible architects of their own defeat. We should learn from their mistakes. When Hitler was appointed chancellor, his conservative predecessor Franz von Papen reacted to the suggestion that he was now at Hitler’s mercy by saying ‘You are mistaken. We’ve hired him’ (Kershaw, 1998: 421). Many others also imagined that Hitler was a biddable beast who could be restrained at the end of a leash. Too late did it become clear that the Nazis had other ideas. Likewise, Mussolini’s lethal intentions weren’t fully appreciated by his opponents until after he had seized power and many of them were in jail (Sassoon, 2007).

Even worse was the position of the social democratic party and the German Communist Party, both with millions of members. The Social Democrats in Italy and Germany endorsed austerity policies that helped turn the misery of their supporters into despair. They also remained committed to parliamentary activity, when the theatre of action had moved to the streets, and failed to see that their right-wing opponents, such as von Papen, were increasingly facilitating rather than resisting the rise of fascism (Mason, 2021). But if this was problematical then the position of the Communists was certifiably insane.

From the early 1920s, the Communist International (Comintern) developed the theory that its main enemy wasn’t fascism but social democracy. This was because, by promoting reformist illusions in capitalism, it was the chief obstacle to socialist revolution (Beetham, 2019). The leaders of social democratic parties were labelled ‘social fascists.’ Such terminology ruled out united action of any kind, including electoral pacts. As Stalin himself infamously put it in 1924:

‘Social-Democracy is objectively the moderate wing of fascism. There is no ground for assuming that the fighting organisation of the bourgeoisie can achieve decisive successes in battles, or in governing the country, without the active support of Social-Democracy. There is just as little ground for thinking that Social-Democracy can achieve decisive successes in battles, or in governing the country, without the active support of the fighting organisation of the bourgeoisie. These organisations do not negate, but supplement each other. They are not antipodes, they are twins.’

In essence, ‘all capitalist regimes, whether parliamentary or dictatorial, were defined as fascist’ (Beetham, 2019: 17). The transition from one form of capitalist rule to the other was unimportant. Those imprisoned or guillotined by the fascists may well have begged to differ. This ‘theory’ led to some extraordinary situations. For example, the Nazis demanded a plebiscite to remove the social democratic government in Prussia in 1931. Intellectually paralysed by brainless directives from Moscow, the German Communist Party (KPD) supported the call for a referendum and urged people to vote in favour of removing the Social Democratic government. It thereby placed itself in the same camp as the Nazis (Haslam, 2021). The referendum failed to achieve its objectives because of low turnout. But it exacerbated existing divisions within the labour movement and made united action against fascism even more difficult than it already was. Looking forward, it is a plus that there is no mass Communist movement in the US today able to exert such a self-defeating influence over opposition to Trumpism.20 Antifascists in our time have the benefit of hindsight. How can this advantage be exploited?

Repudiating Neoliberalism and Promoting and Activist State

I return to Gabriel’s (2016) notion of ‘narrative ecologies.’ Defeating Trumpism requires new narrative spaces that offer hope and an alternative to those models of capitalism that have generated widespread immiseration. It is what George H Bush memorably described as ‘the vision thing.’ Thus, in relation to Donald Trump, Turchin (2023: 15) argues that ‘what gave him the presidency was a combination of conflict among the elites and Trump’s ability to channel a strain of popular discontent that was more widespread and virulent than many people understood, or wanted to understand.’ Trumpist narratives offer simple solutions to complex problems – build a wall between the US and Mexico, throw out immigrants, remove abortion rights, oppose restrictions on gun ownership (to make people safer), and fight culture wars against ‘the liberal elite,’ all of which will ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA). They can only be countered effectively by ones that offer better ideas. In particular, other models of capitalism than the variety of neoliberalism that has so dominated the US are available. In my view, a key resource here is Hodgsons (2015, 2021) argument in favour of what he terms ‘liberal solidarity.’ Among much else, this stresses the potential of a guaranteed basic income, the promotion of social solidarity and a measure of wealth redistribution through, for example, expanding employee share ownership.

Walter (2022: 210) concludes her book on civil wars by imagining how one could be averted in the US. Similar to Hodgson, a central suggestion is that:

‘…the federal government should renew its commitment to providing for its most vulnerable citizens, white, black or brown. We need to undo fifty years of declining social services, invest in safety nets and human capital across racial and religious lines, and prioritise high-quality early education, universal healthcare and higher minimum wage. Right now many working-class and middle-class Americans live their lives “one small step from catastrophe,” and that makes them ready recruits for militants. Investing in real political reform and economic security would make it much harder for white nationalists to gain sympathizers and would prevent the rise of a new generation of far-right extremists.’

As Giroux (2017: 904) points out, ‘any strategy to resist the further descent of the United States into authoritarianism must (recognise) that stopping Trump without destroying the economic, political, educational and social conditions that produced him will fail.’ This approach must involve the explicit repudiation of neoliberalism. From the perspective of liberal solidarity, such a prospectus does not mean the pursuit of total equality in outcomes, or the elimination of market economies. It does involve their reform. A re-imagining of society along these lines is long overdue and a necessary antidote to Trumpism. Advocating the need for a more activist state is not an easy sell, particularly in America, and is certainly not a panacea. We have plentiful examples from the twentieth century which show that centrally planned economies that completely displace market forces are incompatible with democracy (Hodgson, 2015, 2021). State intervention must be judged by the extent to which it solves more problems than it creates, and needs to be held democratically in check. This is a difficult debate. But it is one that it is necessary to have.

Fixing Democracy before It Goes Bust

In parallel with economic renewal, the deficits of American democracy need to be fixed. At present, a majority of US senators are elected by 17% of the population (Tufekci, 2020). This is set to get worse. Marche (2022) points out that:

‘by 2040, 30% of the population will control 68% of the Senate. Eight states will contain half the population. The Senate malapportionment gives advantages overwhelmingly to white, non– college educated voters. In the near future, a Democratic candidate could win the popular vote by many millions of votes and still lose. The federal system no longer represents the will of the American people.’

A key problem is the Electoral College, consisting of 538 electors nominated from each state. A candidate requires 270 votes in the Electoral College to become President. But the College was designed to favour small states and slave states. This means that there has always been the possibility of a candidate losing the popular vote and yet amassing enough votes from the Electoral College to be declared President (Goethals, 2017). This is precisely what happened in 2016, when Hillary Clinton won 65,853,514 votes against Trump’s 62,984,828 – a margin of just over two percent. Yet the Electoral College system ensured that Trump was awarded 306 votes against Clinton’s tally of 232.21 He thus became President. Biden’s win in the popular vote in 2020 was even bigger – by over seven million votes. But Mount’s (2023) analysis of the election concludes that had a few thousand votes gone the other way in five or six seats Trump would have won in the Electoral College. Biden carried Arizona and Georgia by about 10,000 votes and Wisconsin by 20,000. If those votes had been for Trump, and he won those states, the Electoral College vote would have been tied, 269–269, and Trump would have been elected by the Republican House of Representatives.22 There are many ways to describe this, but democratic isn’t one of them.

The abolition of the Electoral College (a system unique to the US), the placing of limits on political donations and the adoption of a modern electoral system throughout the country are clearly needed (Levitsky and Ziblatt, 2023). Calhoun and Taylor (2022) also argue in favour of allowing former felons to vote, a prohibition which disproportionally affects black voters.23 It is one of the many peculiarities of the American system that while a convicted felon can run for the Presidency, they aren’t allowed to vote in Presidential elections. Again, I am not suggesting that achieving such radical reforms would be easy. Those who benefit from the current system would clearly resist it. But the time to engage in the battle for change is now, before Trumpism in one form or another further dismantles existing restraints on its power. No democracy is perfect, but we would miss it once it is gone.24 Marche (2022) puts this in strong terms: ‘The crises the US now faces in its basic governmental functions are so profound that they require starting over.’ In the words of a character in di Lampedusa’s 1958 novel, The Leopard, ‘If we want things to stay as they are, things will have to change’ (p. 19).

Conclusion

Trumpism has consequences far beyond the US. Autocrats throughout the world have been emboldened by Trump’s successes, and many seek to emulate his example. ‘National conservative’ movements have grown up in numerous countries, including a faction within Britain’s Conservative Party. These are committed ‘to the principle of national independence, and to the revival of the unique national traditions that alone have the power to bind a people together and bring about their flourishing.’25 The movement promotes books with titles such as America’s Cultural Revolution: How the Radical Left Conquered Everything; Feminism Against Progress; Regime Change: Towards a Post-Liberal Future; Christian Nationalism; and, The Dying Citizen: How Progressive Elites, Tribalism, and Globalization are Destroying the Idea of America. You get the picture: the world is going to hell in a handcart. In response, and in unmistakeable echoes of Trumpism, national conservatism proposes a future modelled on the mistakes of the past. We should know better. As Pinker (2018: 451) noted, in his robust defence of enlightenment values, ‘Between 1803 and 1945, the world tried an international order based on nation-states heroically struggling for greatness. It didn’t turn out so well.’

We are seeing the rebirth of history rather than its end. What happened before can happen again. But it doesn’t have to. Humanity faces multiple problems, including the existential challenge of climate change. Global co-operation is more vital than ever. Purely national responses, or a wall between the US and Mexico, can’t keep the climate at bay, and will certainly fail to keep out the climate refugees now expected to number in their millions in the decades ahead. Leaders and non-leaders alike can commit to a more inclusive and co-operative future, fight back against racism and poverty, and recommit to democratic forms of government. The battle against Trumpism and for a secure and stable future is a battle of ideas that society cannot afford to lose.

See endnotes and bibliography at source.

Originally published by Impact Factor 20:1 (02.02.2024), DOI:https://doi.org/10.1177/17427150231210732, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.