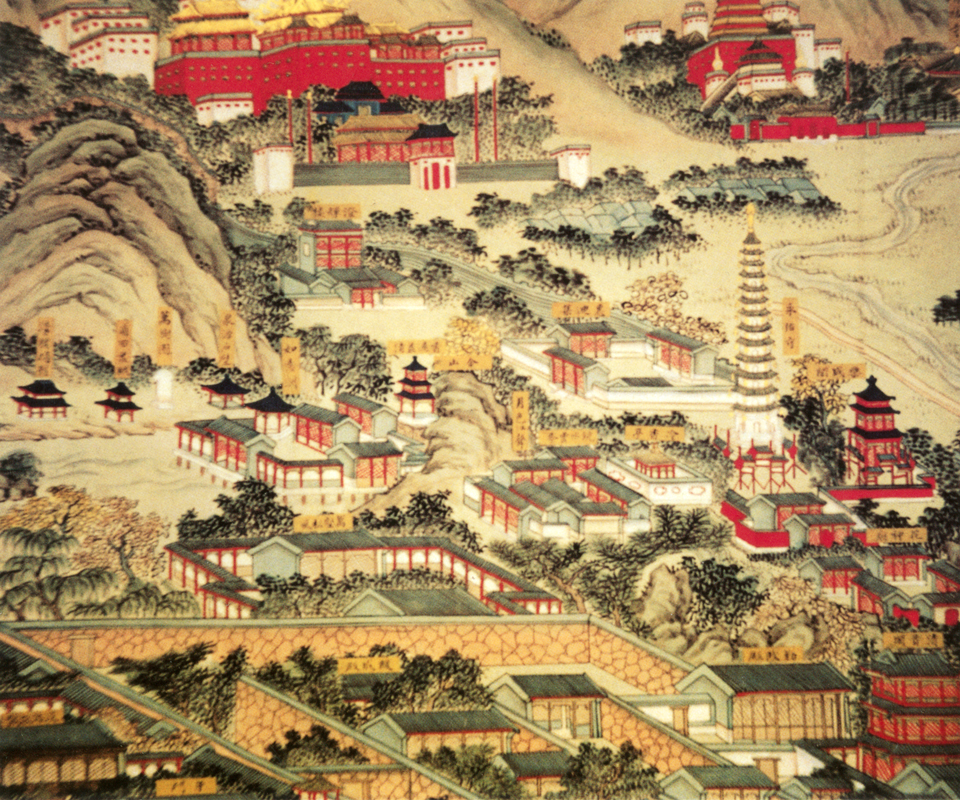

The Yuanmingyuan was a paradise on earth for the Qing emperors.

By Dr. Lillian M. Li

Sara Lawrence Lightfoot Professor Emerita of History

Swarthmore College

Introduction

The Garden of Perfect Brightness—Yuanmingyuan (圓明園)—is the name of one of China’s most iconic monuments and tourist destinations. Its importance, more to Chinese than to foreign visitors, lies in the fact that it was an imperial palace and garden that was almost completely pillaged and destroyed by British and French troops in 1860. As such it has become a symbol of China’s subjugation at the hands of foreign powers in the 19th century, and hence a focal point of modern Chinese nationalism. Ironically its very power as a symbol rests in its physical invisibility—there is almost nothing to see except the ruins of European palaces that formed one part of the entire garden. Although there is “no there there,” the Yuanmingyuan is everywhere in the Chinese national consciousness.

Built in various stages from the early-18th century until its destruction in the mid-19th century, the Yuanmingyuan was at first a scenic retreat for the emperors who wished to escape the heat and formal obligations of the Forbidden City in Beijing. Soon the emperors began to spend more time there, however, and in effect it became the principal imperial residence and place of work. Although the Yuanmingyuan was later described by Western observers as the “Summer Palace,” it was in fact the residence of the emperors for most of the year—not merely in the summer—until it was destroyed in 1860. Later in the century, the Empress Dowager Cixi built a new imperial garden named the Yiheyuan (Cheerful Harmony Garden 頤和園) in a nearby location. Today it is maintained as a major tourist site generally called the New Summer Palace, to distinguish it from the Yuanmingyuan, or “Old Summer Palace.”

The Yuanmingyuan was a paradise on earth for the Qing emperors: beautiful, extravagant, utterly private, and totally their creation—not an inheritance from previous dynasties. It was both a single garden and a complex of different gardens. The word “garden” (yuan 園) describes it better than “palace,” because the landscape setting was far more important than any single structure. The landscapes were not exactly natural scenery, but rather designed, shaped, and constructed. Hills and lakes were planned in ensembles with buildings playing a subordinate role. The landscape was designed to resemble scenes from the Jiangnan region, or Lower Yangzi Valley, from which China’s famous literati poets and painters hailed.

This imperial vision guided the construction of the Yuanmingyuan through several reigns, and is captured in a set of 40 paintings commissioned by the Qianlong emperor in 1744, when he became increasingly ambitious in his building projects. These paintings were taken to France as part of the plunder of the Yuanmingyuan in 1860, and are reproduced in full here in Part 1. They are the only visual evidence that remains through which we can try to imagine the architectural and landscape-gardening aesthetics of the expansive Chinese sections of the “Garden of Perfect Brightness.”

Part 2 of this three-part unit introduces a suite of 20 engravings Qianlong commissioned 40 years later, depicting the European-style palaces that comprised a smaller section of the Yuanmingyuan. The stone ruins and rubble

of these palaces comprise the historical site that tourists commonly associate with the so-called “Old Summer Palace” today.

The third and final part addresses the Anglo-French destruction of the Yuanmingyuan in 1860, the massive looting and “collecting” of precious Chinese art objects that accompanied this, and the place of the Yuanmingyuan in Chinese memory today.

The Emperors

The Qing emperors (1644 to 1911) formed the last of the successive dynasties of China. As “alien” rulers, the Manchus inherited and adopted the cultural norms and political institutions of the previous Han Chinese Ming dynasty (1368 to 1644), at the same time maintaining their own Northeast Asian military organization, customs, and language. After consolidating their power within the former Ming boundaries, the Manchu emperors extended the territory of the empire to include Mongolia, Xinjiang, Tibet, and Taiwan.

During the 18th century, China experienced almost unprecedented peace and prosperity. The population expanded, and the agricultural and commercial economies developed. In the 19th century, however, internal unrest was compounded by foreign aggression. The strong emperors of the 17th and 18th centuries were succeeded by less able descendants who were unable to cope with the cataclysmic events that followed in quick succession.

Three great emperors presided over the high period of Qing rule: the Kangxi emperor (r. 1662 to 1722), the Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723 to 1735), and the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736 to 1795). Together their reigns spanned a century and a half.

The three great Qing emperors were depicted in formal Chinese imperial portraits, identifying these Manchu rulers with their Chinese predecessors. Left – Kangxi emperor, (r. 1662 to 1722); Center – Yongzheng emperor (r. 1723 to 1735); Right – Qianlong emperor (r. 1736 to 1795)

The Kangxi emperor (r. 1662 to 1722) was the second emperor of the dynasty, but was in fact its consolidating founder. He was a man of energy and vision, possessed a great intellectual curiosity, and embodied both the literary and the martial qualities that were valued in a Chinese emperor. As a martial emperor, he put down remaining internal rebellions in the southwest in order to secure Qing rule. He was untiring in the effort to overcome the menace of Mongol tribes in the area to the northwest of the Great Wall, personally leading troops into battle as late as the 1690s.

In order to familiarize himself with the central and southern parts of China, Kangxi made six royal tours to the Jiangnan area, the center of literati culture, beautiful scenery, and abundant agriculture. These tours also served the purpose of winning the allegiance of the Han Chinese elites of the south. After the second tour in 1689, Kangxi commissioned a series of 12 immense scroll paintings to commemorate his travels and each of the major cities and sites he visited.

Presenting themselves as scholars was another way the Manchu emperors cultivated images that would identify them with familiar Chinese traditions. Here, the Kangxi emperor is depicted seated in his library (above, left) and engaged in calligraphy (above, right). / The Palace Museum, Beijing

Kangxi also took care to present himself as a literary emperor, well-educated in Chinese culture. He was diligent in his study of Chinese literature and classics, sponsored the collection of a great library, and liked to have himself painted as a scholar in his studio. The court artists of such portraits, formal and informal, were usually unidentified.

Although the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723 to 1735) ascended the throne under circumstances that aroused suspicion, he nevertheless proved to be an extremely diligent and able ruler. Unlike his father, who liked to ride and hunt, Yongzheng devoted himself to administration of the empire. Historians consider that his greatest accomplishments were in the realm of strengthening governmental institutions and practices.

Following the examples of his illustrious grandfather and strong father, the Qianlong emperor (r. 1736 to 1795) further strengthened the empire. In the first half of his long reign, he achieved good governance of the provinces and witnessed unprecedented economic prosperity. His last decades, on the other hand, were characterized by internal disturbances, bureaucratic corruption, and his own personal failings that allowed power to fall into the hands of a palace guardsman, He Shen, who amassed tremendous wealth.

The Forbidden City

The entire north-south axis of Beijing is realistically depicted in this 1767 painting by court artist Xu Yang. Commercial activities are shown south of the Zhengyang Gate (at the bottom of the painting). At the center is the main gate to the Forbidden City, the Tiananmen (the Gate of Heavenly Peace). Several impressive gates and palace structures lead to the main throne hall, the Taihedian. Beyond the Forbidden City is Coal Mountain, a prominent landmark. The painting’s title is based on a poem by the Qianlong emperor entitled “Bird’s Eye View of the Capital.” / The Palace Museum, Beijing

The Qing emperors established their capital at Beijing and ruled from the Forbidden City, the palace complex that had been built by a Ming emperor in the 1420s at the same location where the Mongol Yuan dynasty (1279 to 1368) had built its palace and capital. Today, the Forbidden City is run as a national museum that symbolizes both the present-day power of Beijing and the imperial past. The Forbidden City was the center of ceremonies and residence of the imperial family and servants including eunuchs. It was the innermost city of a series of nested cities, each defined by a set of walls. Surrounding it was the Imperial City, with government offices and the residences of some princes and officials. Surrounding this was the remainder of the Inner City, where the Manchu bannermen had their separate headquarters. South of this entire Inner City complex was the Outer City, where ordinary Han Chinese resided and worked, and where commerce and entertainment flourished.

The many walls and gates that surrounded each of these “cities” delineated the segregation of society by rank and function. The imposing formal reception halls of the Forbidden City were located at the front of the complex, while in the rear the space was divided into numerous complexes housing the empresses, imperial women, and servants.

Foreign envoys bearing tribute are depicted in a procession, including elephants, outside the gate to the Forbidden City. / The Palace Museum, Beijing

Entry to the Forbidden City was highly restricted. Its vast spaces, massive public halls, and multiple gates were meant to inspire a sense of awe. Envoys or high officials approaching the Hall of Supreme Harmony could not fail to understand their subordination to imperial authority. Even today the distance tourists must walk from the Gate of Heavenly Peace in the south to the northernmost gate or exit conveys an overwhelming impression of what imperial power meant.

The Qing Emperors as Builders

The private courtyards, pavilions, gardens, and residences were constantly expanded, renovated, or redesigned under the successive emperors. The Qianlong emperor was an avid builder within the Forbidden City and elsewhere in Beijing and the capital area. The Empress Dowager Cixi, who held a great deal of power in the late-19th century, resided there when she served as regent for her nephew and grandnephew, and oversaw new construction and decoration. Although they tirelessly built new temples, private residences, and other structures within Beijing, the emperors also sought to leave the confinement of the Forbidden City and the unpleasant summer climate of the capital. Each summer, for example, Kangxi escaped north of the Great Wall to the Mulan hunting grounds in Manchuria—the Manchu homeland—where he hunted, engaged in archery and other competitive activities, and generally enjoyed the fresh air of the mountains.

In 1703, Kangxi began construction of another palace and garden complex at Chengde (also known as Rehe or Jehol) named “The Mountain Resort for Escaping the Summer Heat”—Bishu shanzhuang—and development of this imperial retreat continued throughout the 18th century. At Chengde, as at the Yuanmingyuan, landscape scenes were designed to resemble famous Jiangnan temples or vistas. [2]

Although Kangxi’s son, the Yongzheng emperor, had no interest in hunting, all the other Qing emperors regularly summered at Chengde when possible. The Qianlong emperor, Yongzheng’s son, spared no expense in expanding the gardens, pavilions, libraries, and residences there. The mountain resort also served a diplomatic function, receiving Central Asian and other foreign emissaries.

Appendix

Notes

- The iconography of this image is discussed in Worshiping the Ancestors: Chinese Commemorative Portraits, edited by Jan Stuart and Evelyn S. Rawski (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2001), pp. 120-21.

- Forêt, Philippe. Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000), p. 70. This painting and artist are discussed in China: The Three Emperors, 1662–1795, edited by Evelyn S. Rawski and Jessica Rawson (London: Royal Academy of the Arts, 2005), pp. 393-94.

- Forêt, Color Plate 3, and pp. 49-53.

Sources

- Attiret, Jean Denis (1702–1768). A particular account of the Emperor of China’s gardens near Pekin: in a letter from F. Attiret, a French missionary, now employ’d by that emperor to paint the apartments in those gardens, to his friend at Paris. Translated from the French by Sir Harry Beaumont (London: printed for R. Dodsley; and sold by M. Cooper, 1752).

- Barrow, John. Travels in China, containing Descriptions, Observations, & Comparisons made and collected in the course of a short residence at the Imperial Palace of Yuen-ming-yuen and on the subsequent journey from Pekin to Canton, first American ed. (Philadelphia: Wm. McLaughlin, 1805 [also London: 1806]).

- Bell, John. A Journey from St Petersburg to Pekin, 1719—22. Edited and with introduction by J. L. Stevenson (New York: Barnes and Noble, 1966).

- Chambers, Sir William. A Dissertation on Oriental Gardening (Dublin: printed for W. Wilson, 1773).

- China: The Three Emperors, 1662–1795, edited by Evelyn S. Rawski and Jessica Rawson (London: Royal Academy of the Arts, 2005).

- Chiu, Che Bing. Yuanming Yuan: le Jardin de la Clarté Parfaite (Bescançon: Editions de l’Imprimeur, 2000).

- Danby, Hope. The Garden of Perfect Brightness: The History of the Yuan Ming Yuan and of the Emperors Who Lived There (Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1950).

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley. Cambridge Illustrated History of China, 2nd edition (Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

- The Emperor’s Private Paradise: Treasures from the Forbidden City, edited by Nancy Berliner (New Haven and London: Peabody Essex Museum in association with Yale University Press, 2010).

- The Forbidden City [De Verboden Stad]: Court Culture of the Chinese Emperors, 1644-1911. (Rotterdam: Museum Boymans-van Beuningen, 1990).

- Forêt, Philippe. Mapping Chengde: The Qing Landscape Enterprise (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2000).

- Juanqinzhai: In the Qianlong Garden,The Forbidden City, Beijing, edited by Nancy Berliner (London: Scala Publishers, 2008).

- Kangxi, Empereur de Chine, 1662–1722: La Cité interdite à Versailles, Musée national du chateau de Versailles, 27 janvier-9 mai 2004. Réunion des musées nationaux, Paris 2004.

- Kutcher, Norman A. “Unspoken Collusions: The Empowerment of Yuanming Yuan Eunuchs in the Qianlong Period,” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies 70.2 (Dec. 2010), pp. 449-495.

- Landscapes Clear and Radiant: The Art of Wang Hui (1632-1717), Hearn, Maxwell J., ed. (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008).

- Li, Lillian M., Dray-Novey, Alison J., and Haili Kong. Beijing: From Imperial Capital to Olympic City (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007).

- Malone, Carroll Brown. History of the Summer Palaces under the Ch’ing Dynasty (Urbana: University of Illinois, 1934).

- Naquin, Susan. “Giuseppe Castiglione/Lang Shining: A Review Essay.” T’oung Pao 95(2009), pp. 393-412.

- Pirazzoli-T’Serstevens, Michèle. Giuseppe Castiglione, 1688-1766: Peintre et architecte à la cour de Chine (Paris: Thalia, 2007).

- Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei, edited by Wen C. Fong and James C. Y. Watt (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Taipei: the National Palace Museum, 1996).

- Qianlong yupin Yuanmingyuan 乾隆御品圓明園 (Qianlong’s Imperial treasure Yuanmingyuan), ed. Guo Daiheng 郭黛姮 (Hangzhou: Zhejiang guji chubanshe, 2007). “Yupin”

- Sirén, Osvald. Gardens of China (New York: The Ronald Press, 1949).

- Staunton, Sir George. An Authentic Account of an Embassy from the King of Great Britain to the Emperor of China, 2 vols. and a folio atlas of plates (London 1797–98).

- Strassberg, Richard E., “War and Peace: Four Intercultural Landscapes,” in China on Paper: European and Chinese Works from the Late Sixteenth to the Early Nineteenth Century, edited by Marcia Reed and Paola Demattè (Los Angeles: The Getty Research Institute, 2007), pp. 88-137.

- Tangdai 唐岱 and Shen Yuan 沈源. Yuanmingyuan sishi jingtu yong 圓明園四十景圖咏 (40 Scenes of Yuanmingyuan) (Beijing: Zhongguo jianzhu gongyuan chubanshe, 2007). “40 Scenes”

- Wong, Young-tsu. A Paradise Lost: The Imperial Garden Yuanming Yuan (Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2001).

- Worshiping the Ancestors: Chinese Commemorative Portraits, edited by Jan Stuart and Evelyn S. Rawski (Washington, D.C.: Freer Gallery of Art, 2001).

- Yuanshi de huihuang: Yuanmingyuan jianzhu yuanlin yanjiu yu baohu 远逝的辉煌:圆明园建筑园林研究与保护?Brilliance of the distant past: Research and protection of Yuanmingyuan’s architecture and gardens), edited by Guo Daiheng 郭黛姮 (Shanghai: Shanghai keji jishu chubanshe, 2009).

Originally published by Visualizing Cultures, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 United States license.