The United States stands at a crossroads where economic divergence threatens to harden into a permanent social fracture. The K-shaped economy is no longer a forecast but a lived reality.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

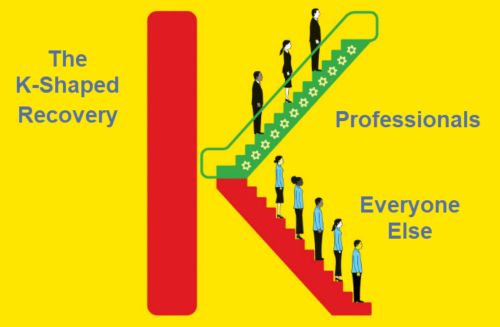

America is splitting along a fault line that is no longer hidden in statistical tables but visible in the daily lives of its people. For the top tier of households (the investors, asset holders, professionals in technology and finance) this moment can feel like a continuation of prosperity. For the majority, however, wages are flat, debts are rising, and the price of basic goods has been pushed upward by policies that claim to protect but instead punish. What emerges is not a unified recovery or even a shared stagnation, but a bifurcation: the so-called K-shaped economy, in which the top 10–20 percent rise while the bottom 80–90 percent are left to decline.

The story is as old as capitalism itself, class divide entrenched through the unequal distribution of growth, yet today it is sharpened by two powerful forces. First, the revolution of artificial intelligence and automation, which magnifies returns to capital and to the already-skilled, while stripping security from vast sectors of the workforce. As one analysis warned, the so-called AI boom risks becoming another round of dislocation for the very people it promises to serve, potentially hollowing out whole regions of middle-class employment. Second, and even more immediate, is the return of protectionist tariffs under Donald Trump, measures designed for political theater but carrying real economic consequences for working families.

Tariffs act as stealth taxes, levied most heavily on those who can least afford them. They make everyday necessities more expensive, disrupt global supply chains, and sow uncertainty across industries that rely on predictable trade flows. Evidence is already mounting that Trump’s aggressive tariff agenda is not only raising costs but also threatening growth, setting the stage for bailouts, a potential recession, and even the specter of another depression. For the wealthy, financial cushions and diversified portfolios will blunt the blow. For the rest, the effect will be harsh, immediate, and inescapable.

What follows argues that the K-shaped economy is not simply a descriptive metaphor for inequality but a warning about the trajectory of American society. If current policies continue, from tariffs that punish consumers to automation that enriches owners, the United States will not just drift toward divergence; it will accelerate into a permanent two-track future. The stakes are nothing less than the health of democracy itself, for economic fracture has always been a prelude to political crisis.

What Is a K-Shaped Economy?

The alphabet has long served as a metaphor for economic trajectories. We speak of “V-shaped” recoveries, where a steep fall is met by a swift rebound; of “U-shaped” slow climbs back to stability; and of “W-shaped” false starts that rise only to collapse again. But the letter K is different. It suggests not a shared path but a divergence: one arm pointing up, the other down. In today’s United States, this divergence is visible everywhere, in earnings, wealth accumulation, job security, and even life expectancy.

Economists and journalists alike have taken up the term to capture what ordinary people already know: while one segment of America flourishes, the rest struggles to stay afloat. Middle-class families find themselves squeezed by stagnating wages and rising costs, even as wealth at the top compounds through financial markets and real estate. The K-shape is not temporary. It is becoming the defining contour of the American economy.

The mechanics are straightforward. At the top, asset appreciation and technological gains create windfalls. Those who already hold capital in stocks, property, intellectual property, or venture investments see outsized returns. The AI revolution accelerates this dynamic, rewarding firms and investors positioned to harness new tools while threatening to displace workers in sectors once considered stable. Analysts have warned that unless managed carefully, AI could become another wedge that amplifies inequality rather than narrowing it.

Meanwhile, the majority of households live almost entirely from wages, and wages have lagged behind both productivity and costs for decades. Housing, health care, and education rise relentlessly, consuming a greater share of disposable income. Inflation, aggravated by trade disruptions and tariffs, hits the working and middle classes hardest because they spend proportionally more of their income on consumption. The result is not simply slower growth at the bottom but outright decline: less savings, more debt, more insecurity.

What makes the K-shape dangerous is its feedback loop. As those at the bottom slip further behind, they lose not only purchasing power but also mobility. Fewer families can invest in higher education or property, locking them out of the very engines of upward movement. Lower demand dampens economic dynamism, while the tax base shrinks, eroding the public goods (schools, infrastructure, health systems) that sustain opportunity. Over time, the divergence hardens into class stratification.

This dynamic is not new. Inequality has ebbed and flowed across American history. But today’s divergence is sharpened by globalization, financialization, and technological disruption, all operating in tandem. And under Trump’s renewed embrace of tariffs and economic nationalism, the forces pushing the arms of the K further apart are being accelerated rather than restrained.

Tariffs as an Inequality Accelerator

Tariffs are often defended as patriotic tools to protect American workers, but the reality is more brutal: they function as regressive taxes that fall hardest on those least able to bear them. When Trump champions blanket tariffs as a way to “bring jobs back,” what he is really imposing is a stealth levy on households already under strain. Studies consistently show that tariffs are passed along to consumers in the form of higher prices. This means the cost of imported goods, everything from clothing to electronics to household essentials, climbs, and low- and middle-income families, who spend a larger share of their earnings on consumption, shoulder the greatest burden. Analysts have demonstrated that tariffs fall disproportionately on lower-income households, turning a political slogan into a regressive tax policy.

The scale of Trump’s proposed tariffs makes the threat impossible to ignore. The nonpartisan Penn Wharton Budget Model projects that his trade policies could reduce long-run U.S. GDP by 6 percent and wages by 5 percent, a staggering contraction in national wealth and household income. Far from strengthening America, these measures risk hollowing out growth, choking investment, and slowing job creation. The very workers Trump claims to protect are those most likely to suffer.

Tariffs also inject chaos into the broader economic environment. Trump’s penchant for sudden, sweeping announcements creates what analysts have described as an “economy of uncertainty.” When firms cannot predict supply chains or costs, they delay investments, slow hiring, and scale back operations. This hesitation ripples outward, hitting contract workers, suppliers, and service industries that depend on stable industrial activity. For precarious workers and smaller businesses, the damage can be immediate and irreversible.

The distributional impact is stark. As the Institute for New Economic Thinking has argued, the second Trump administration’s tariff agenda is likely to worsen inequality and erode living standards for the working and middle classes. By contrast, the wealthiest Americans, whose portfolios are insulated by capital gains, stand to endure little net harm and may even benefit from accompanying tax cuts and corporate concessions. An analysis by the Center for American Progress concluded that average incomes will decline for nearly all Americans except the top 1 percent, revealing how tariffs redistribute upward under the guise of nationalism.

History should serve as warning. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, often remembered as an accelerant of the Great Depression, demonstrated how protectionism can trigger retaliation, collapse trade flows, and deepen economic crises. Today, in a far more globalized world, Trump’s tariffs risk sparking cascading effects that extend well beyond U.S. borders. As one analysis from the Centre for Economic Policy Research put it bluntly, Trump is disregarding the lessons of history, and the likely outcomes are predictable: reduced growth, higher prices, and wider inequality.

In short, tariffs operate as accelerants on the K-shaped economy. They enrich the few who can weather or exploit volatility, while punishing the many who have no margin to absorb higher prices and economic shocks. The policy is not just bad economics; it is class war disguised as populism.

The Pathway to Bailouts, Recession, and System Stress

The logic of tariffs does not stop at higher prices. Their ripple effects move outward, compounding pressure across the economy until cracks appear in the very structure of growth. If the K-shaped economy describes the divergence between winners and losers, Trump’s tariffs represent a force that not only widens the arms of the K but also destabilizes the middle altogether, edging the country closer to systemic stress.

Warnings are already mounting. Citigroup analysts recently placed the odds of a U.S. recession at nearly 45 percent, citing tariffs as a central factor in slowing demand. Other forecasters echo this concern, noting that escalating protectionism functions as a stagflationary shock: it raises prices while suppressing growth. Investors and businesses are already bracing for the fallout, with capital expenditures slowing as uncertainty ripples through markets. This is how policy designed for political theater begins to erode the foundations of economic stability.

In such a downturn, bailouts almost inevitably follow. Large firms with political clout (banks, industrial giants, multinational corporations) will not be left to fail. History has shown that when crisis strikes, Washington moves quickly to stabilize markets through emergency interventions. But these bailouts, while necessary to prevent collapse, are rarely structured to protect ordinary households. Instead, they preserve the wealth of capital owners while offering only minimal relief to those most damaged by the downturn. In effect, the state rescues the top half of the K while leaving the bottom half to slide further down.

This dynamic feeds a vicious cycle. As firms contract, layoffs spread, disproportionately hitting the working and middle classes who are already struggling with higher consumer prices. Demand weakens further, creating the conditions for deeper job cuts. State and local governments, reliant on income and sales tax revenue, see their budgets squeezed, leading to cuts in services that are vital for mobility: schools, health care, infrastructure. The arms of the K are not only diverging; the lower arm is actively being pushed downward by systemic neglect.

The global dimension cannot be ignored. Tariffs invite retaliation. Trading partners have historically responded in kind, targeting U.S. exports and further undermining domestic industries. What begins as a nationalist gesture quickly becomes a trade war, shrinking markets for American goods and hurting the very sectors tariffs claimed to protect. In a world where supply chains are deeply interlinked, the damage spreads quickly. Companies reliant on global inputs face rising costs, while farmers and manufacturers find overseas markets closing. This, too, reinforces the need for bailouts, deepens fiscal strain, and accelerates the downward track of the majority.

The warning signs are thus not speculative. They are visible in projections, in business behavior, and in historical precedent. Trump’s tariffs have set the U.S. on a path toward a cycle of rising prices, shrinking wages, and eventual crisis management through bailouts that protect capital at the expense of labor. The K-shaped economy, already embedded, is poised to sharpen into a permanent fracture, one arm buoyed by state intervention, the other weighed down by systemic neglect.

Countercurrents: Why the K-Shape Might Be Reversible

The K-shaped economy is not destiny. Divergence is the outcome of choices (policy choices, institutional choices, cultural choices) and what has been constructed can, in principle, be dismantled or redirected. To imagine reversal is not naïve optimism but historical realism. Across the twentieth century, the United States experienced moments of extraordinary inequality, yet also periods of relative compression when reforms leveled the field and expanded opportunity. The question is not whether the K can be softened, but whether there is the political will to confront the interests that profit from its sharp edges.

One path lies in tax policy. Wealth in the United States is increasingly concentrated, with the top 1 percent controlling vast portions of national assets, while median households hold little beyond home equity. A progressive taxation system – one that seriously confronts capital gains, estate transfers, and corporate loopholes – could help shift resources back toward the public sphere. Similar efforts have been advanced in Europe, and in the U.S., proposals for wealth taxes and stronger corporate taxation remain part of mainstream debate. Without such redistribution, the upward arm of the K will continue to rise unchecked.

Another path lies in labor power. Decades of weakening unions have left workers with little leverage against stagnating wages and precarious conditions. Revitalizing collective bargaining rights, enforcing wage floors, and expanding protections for gig and contract workers would strengthen the bargaining position of the majority. Research consistently shows that unionized workers secure higher pay and better benefits, reducing inequality not only within firms but across entire sectors. In a K-shaped economy, rebuilding labor is one of the few tools capable of bending the downward arm back upward.

Public investment also plays a crucial role. A society that neglects education, health, and infrastructure erodes the very foundations of opportunity. Expanded access to affordable childcare, universal healthcare, and debt relief for students would not only ease burdens but also stimulate productivity and demand. Economists argue that investments in public goods yield long-term growth dividends, far outweighing their costs. In this sense, reversing the K is not just about fairness but about efficiency.

Trade and industrial policy must also be recalibrated. Protectionism as practiced today is blunt and politically motivated, yet a carefully designed strategy could safeguard industries without punishing consumers. Multilateral approaches, consistent rules, and targeted support for strategic sectors could provide stability and resilience while avoiding the destructive spiral of tariff wars. Such policies, when tethered to industrial modernization and green transition, could create a new base of well-paid jobs rather than erode them.

None of this will come easily. The interests benefiting from divergence are powerful, and the political system itself is skewed toward those with wealth. Campaign finance, lobbying, and partisan gridlock ensure that reforms face immense resistance. Yet history reminds us that crises often open windows for change. The Great Depression produced the New Deal; postwar inequality gave way to a middle-class boom; even the turbulence of the 1970s eventually spurred new institutional frameworks. Whether the current moment leads to reform or deeper fracture depends not on inevitability but on the balance of power and imagination.

Conclusion

The United States stands at a crossroads where economic divergence threatens to harden into a permanent social fracture. The K-shaped economy is no longer a forecast but a lived reality, visible in every widening gap between those who own assets and those who live paycheck to paycheck. Tariffs, far from protecting the working class, are accelerating this divergence: raising consumer prices, depressing wages, and inviting retaliations that risk dragging the country toward recession and bailouts that preserve wealth at the top while abandoning the rest.

History warns us what happens when inequality metastasizes. The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act deepened the Great Depression by collapsing trade and amplifying class suffering, and today’s protectionism risks repeating that catastrophe on a global scale. The lesson is plain: tariffs and economic nationalism may win headlines, but they destabilize the very foundations of prosperity. Left unchecked, they will widen the arms of the K until one side rises into untouchable wealth and the other descends into despair.

Yet divergence is not destiny. The United States has the tools to blunt inequality: progressive taxation, revitalized labor rights, strategic investment in public goods, and trade policies that protect without punishing. What is missing is political will. As long as leaders choose performance over policy, slogans over substance, the divide will sharpen, and with it, the fragility of democracy itself. Economic fracture breeds political instability, eroding trust in institutions and fueling populist anger that can easily be turned against the very freedoms meant to protect citizens.

The stakes are therefore not merely financial but existential. Will America accept a permanent two-track economy, where the top flourishes while the majority fights to survive? Or will it confront the forces accelerating the divide, reimagining growth as a shared endeavor rather than a private windfall? The answer to that question will shape not only the future of American prosperity but the survival of its democratic experiment.

Originally published by Brewminate, 10.07.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.