The secularly-oriented segment of the population has increased the most since the mid-1960s.

By Dr. Josef Braml

Head, The Americas Program

German Council on Foreign Relations

Introduction

The political awakening of conservative Evangelicals and fundamentalist religious movements since the early 1980s is one of the most important cultural changes in the United States as it establishes new political structures that influence domestic and foreign policy-making. The Christian Right’s voters and interest groups (political action committees, grassroots organizations and think tanks) not only have an impact on elections, but also influence the policy agenda. National security issues, in particular the fight against terrorism, play a central role for another reason: they may strengthen the cohesion of a heterogeneous electoral coalition and, thus, help to establish Republican control over Congress and the White House.

Religion Matters

The religious landscape in the U.S. is characterized by its diversity. The percentages of various denominations within the population as a whole have remained relatively constant (see Table 1). In total, over 80% of Americans are Christian. Protestants constitute the largest denomination, including over half of the entire population. The more conservative (white) Evangelicals have become the largest single group, constituting 25.4% of the total population and relegating the more liberal Mainline Protestants (22.1%) to second place. The percentage of black Protestants has also shrunk since the 1960s to barely 8% in 1996. Roman Catholics constitute 21.8% of Americans.

The secularly-oriented segment of the population has increased the most since the mid-1960s and presently forms 16.3%, almost twice as much as in 1965. The trend toward secularization mobilized committed religious leaders, especially Evangelical Protestants, to counter the “decadence” and “disintegration of moral values” in society. Evangelical Protestants, foremost among them the traditionalists, share an individualistic belief system that is centered on the afterlife. They do not believe in social reform. Instead, their activism is mainly focused on restoring traditional values and beliefs, which they want to defend against modernity and liberalism.

American observers have noted a “diminishing divide” between religion and politics:[2] “True believers,” especially white Evangelical Protestants, have become more active politically. White Evangelical Protestants now comprise about one quarter of registered voters,[3] 24% in 2000, and display considerable religious persuasiveness and political zeal. The majority of this group are close to the Republican Party.[4] Within three decades, from 1964 to 2000 (see Figure 1), the percentage of white Evangelicals who are Republican has increased both among the “committed” (from 42% to 74%) and among the “others” (from 30% to 49%). This trend has been especially pronounced since the mid-1980s.[5] In addition, the percentage of Republican voters among Catholics has doubled.

Denominational membership has become an indicator of ideology and political outlook. Moreover, the depth of personal belief and degree of activism are other important indicators of political behavior. “Committed” or practicing members distinguish themselves from others by factors such as the frequency of church attendance and prayer, the exceptional role that faith plays in their everyday life, and adherence to traditional beliefs, such as the belief in heaven and hell.[6] Committed members of a congregation generally display more conservative political outlooks and have a markedly higher preference for the Republican Party. In contrast, the less committed tend to prefer the Democratic Party.

6President George W. Bush’s campaign strategists have not been unaware of this trend. The head of these strategists, Karl Rove, who has enjoyed the President’s unconditional trust emphasizes:

First of all, there is a huge gap among people of faith. […] You saw it in the 2000 exit polling, where people who went to church on a frequent and regular basis voted overwhelmingly for Bush. They form an important part of the Republican base.[7]

Thus, Christian Right political strategists like Gary Bauer, President of the organization American Values, have a highly developed self-image and self-confidence:

The label to some in the liberal media is almost a cursed word, but it is an accurate description. Really, it is nothing more than people who regularly attend church and who are politically conservative and that is a fairly significant portion of the American population and it is a major percentage of the Republican vote. […] People who attend church once a week or more frequently voted overwhelmingly Republican. And people who seldom or never attended church voted overwhelmingly for Al Gore. So it is a very big dividing line in American politics.[8]

This divide has been working in favor of Republicans. Empirical regression analyses, which illustrate the specific weight of distinct factors, show that in the U.S. “the influence of religious affiliation on voting behavior is substantial, rivalling that of demographic factors such as income and education.”[9] Religious factors have increasingly influenced Americans’ voting behavior since the 1980s, thanks to political entrepreneurship and professional mobilization of the religious vote.

Mobilizing the Religious Vote

It is important to note that well into the 1960s many devout citizens shunned political activities. Indeed, to this day, many Evangelicals are still wary, because their individual hopes for salvation focus on the afterlife. This means that their earthly commitment is primarily devoted to maintaining traditional values and practices and protecting them against the modern world. However, the Supreme Court decision on abortion (Roe v. Wade, 1973) and the questioning of tax benefits for Christian schools in 1978 politicized many of the faithful, who had already been alarmed by the abolition of school prayer in the 1960s.[10] Furthermore, the emergence of feminist political activism, the gay rights movement, civil rights activists and environmentalists mobilized those who felt that traditional values were being threatened. Political activism among Evangelical Protestants became acceptable, although not without lengthy theological rumination, in which the blessing of fundamentalist religious leaders played an important role.

Both the political clout of the Christian Right and its political preference for or affiliation with the Republican Party have not always been obvious. The Christian Right’s political weight became evident with Pat Robertson’s primary campaign in 1987/1988. Although Robertson lost to the then Vice-President George H.W. Bush, the father of George W. Bush, the Evangelicals proved that they had evolved into a cohesive force within the Republican constituency. They became instrumental in Bush’s eventual victory, as Pat Robertson sent his troops into battle for the Republicans during the main campaign. Almost three out of four (70%) Evangelicals ended up voting for Bush. Thus, the Evangelical voter base was even able to compensate for losses among Catholic voters.[11]

Two cardinal mistakes prevented Bush’s re-election. He underestimated the importance of economic issues and he lacked the support of the Christian Right. In 1992, only 56% of Evangelicals voted for him.[12] George W. Bush drew his own conclusions from his father’s defeat. He was the liaison to the Christian Right in Bush Senior’s campaign. In this capacity, he met Christian Right activists and established a network that would form the cornerstone of his own career. His later election victory―and his defeat of John McCain in the primaries―would not have been possible without the support of these allies.

With 71% of Evangelicals voting for him, George W. Bush not only surpassed the Evangelical voter share of his father, but even outdid Ronald Reagan’s support among Evangelical voters in the 1984 election.[13] “For the first time,” recalled Kevin Phillips, a former Republican campaign strategist and long-time political observer, “a Republican presidential victory rested on a religious, conservative, southern- centered coalition led by a bloc of white Protestant fundamentalists and evangelicals,”[14] which constituted 40% of George W. Bush’s total number of votes.[15] This voter base presented itself with considerable self-confidence: “Karl understands the importance of this segment of his coalition, and I think the president understands it,” Rove intimate Richard Land, President of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, explained. Land added: “The president feels that one of the contributory factors to his father’s loss is that he didn’t get as many evangelical votes as Reagan did.”[16]

The election results in November 2004 confirmed this view: George W. Bush not only enhanced his voter share among Catholics, he even managed to increase his already high support among white Evangelicals from 71% in 2000 to 76% in 2004 (or even 78% according to the National Exit Polls).[17] Thus, the Christian Right again constituted the key constituency of the Republican base. Nevertheless, it takes two equal partners for a lasting political marriage:

If the GOP needs religious conservatives, the converse is true as well: Evangelicals, social-issue conservatives, and particularly the Christian Right need the Republican Party. Religious conservatives are most effective when they participate in a broader conservative coalition, and the Republican Party is the most accessible institution for this purpose. Becoming a partner in such a coalition is not easy: it requires equal measures of compromise, militancy, and sophistication.[18]

This, in a nutshell, is how experts on the Christian Right and long-time observers of the American political landscape have described the symbiotic power relationship between the Republican Party and the Christian Right’s organizational network.

In the past few decades, the Republican Party has been able to make significant inroads into the so-called Bible Belt in the South―the region with the largest population of Evangelicals.[19] Today, the Evangelical strongholds are in the rural South and to a certain degree in the Midwest among older, somewhat less educated citizens. Income is not a factor distinguishing Evangelicals from other segments of the population (see Table 2).

Activist Evangelicals, especially those in the Southern states, have become an important element of the Republican constituency. A more in-depth analysis of case studies in individual states where the Christian Right has been involved, such as Florida, South Carolina, Virginia, Texas, Iowa, Kansas, Michigan, Minnesota, Colorado, California, Maine, Oregon and Washington,[20] allows one to come to the following conclusions: The Christian Right is strongest in the South―in South Carolina, Virginia, Texas and Florida―and has evolved into an established, even dominant part of the Republican Party organizations in those states. The Christian Right also has strongholds in the Midwest and influences the Republican Party organizations in Michigan, Iowa, Kansas and Minnesota.[21] It is important to note that Florida, Michigan, Iowa and Minnesota are so-called “battleground states,” hotly contested states in presidential elections, where every vote counts and where the Christian Right’s organization and mobilization of potential voters can decide victory or defeat.

The Christian Right has established itself in the body politic. It has moved from its marginal position in society towards the political mainstream and the center of political power struggles. This development crowns a long and winding learning process of the Christian Right, which led it from initial fundamentalist sectarianism to political pragmatism. The Christian Right’s consolidation of its position as a force in American politics is the fruit of the seeds that the latest generation of political professionals has sown.

Political figures enjoying religious authority and blessed with political talent, such as Gary Bauer, James Dobson, Jerry Falwell, Franklin Graham, Ralph Reed, Pat Robertson or Paul Weyrich, to name but the most prominent, gave the abstract concept of the “Christian Right” a higher profile and cohesion.

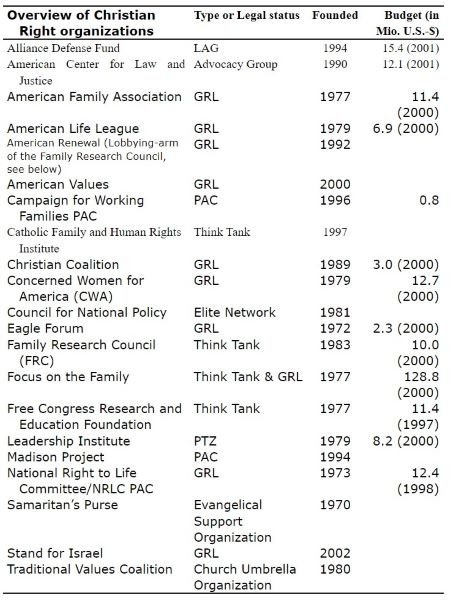

Organizations of the Religious Right

Already in the early 1970s, the late Paul Weyrich was developing strategies to bring together various denominations in a political ecumenical movement. At a meeting in Lynchburg, Virginia, in 1979, organized by the late Reverend Jerry Falwell, Weyrich proposed the idea of creating a moral majority in America. The “Moral Majority” was described as a movement across denominational lines engaging politically on a platform of common issues, namely a pro-life, pro-family, pro-traditional morality, pro-America and pro-Israel platform. Thus, abortion was no longer an issue just for Evangelicals or Catholics. In the view of this political alliance of faith, abortion had become a moral issue across denominational lines. In the words of the late Jerry Falwell, the Moral Majority did not see itself as a purely Christian organization, but was willing to cooperate with anyone “who shared [its] views on the family and abortion, strong national defense, and Israel.”[22] Thus, the Christian Right or rather the Religious Right occupied key political territory.

Even though the Moral Majority as an organization vanished, the idea of cultivating a moral majority has been transmitted to a new set of politically even more active professional organizations, like Gary Bauer’s organization American Values and his political action committee, the Campaign for Working Families PAC. Another political entrepreneur, James Dobson, founded the Family Research Council (FRC), and his organization, Focus on the Family. The National Right to Life Committee (NRLC) had already been founded as a response to the Supreme Court’s Roe v. Wade ruling on abortion in 1973. The organization Concerned Women for America (CWA) understands itself as America’s “largest public policy women’s organization.” In 1972, Catholic activist Phyllis Schlafly founded the Eagle Forum, a small grassroots organization highly regarded in conservative circles because of its pioneering role in fighting “excessive feminism.”

Political Currency

Peter Lösche, an expert in political systems, provides a valuable summary of the situation:

Considering all the New Right Organizations as a whole, they fulfil the tasks that are exclusively assumed by parties in the western European parliamentary systems of government. The New Right organizations often assemble young, highly intelligent and cold-as-ice political managers who not only know how to organize, mobilize, manipulate and campaign, they also make use of new technologies to do so.[23]

The Christian Right organizations mentioned above recruit their members from practicing religious conservatives of all denominations. It is important to note that the Evangelicals are central to all the major Christian Right organizations.[24] The Religious Right’s strategy has been to “save human lives, baptize them and register them to vote.”

In the late 1970s, only about half of the Evangelicals were registered voters (the average percentage of registered voters in the total population was 70%). In order to mobilize the enormous army of approximately 60-70 million potential voters, the churches became involved in voter registration initiatives. Today, white Evangelical Protestants are even more active than the average population in America and proportionately, more Evangelicals are registered to vote: 82% compared to a national average of 77%. White Evangelicals are also more active voters: 65% of them compared to a national figure of 61% indicated that they had cast their votes in the in 2000 and 2002 elections.[25] As a result, the Christian Right’s organizational networking pays off during campaigns. Not only is the Christian Right permanently campaigning and thus mobilizing its constituency and expanding the Republican voter base at the grassroots level, but its highly evolved organizational structures also constitute an increasingly important financial pillar.

Back in the 1970s, the Christian Right communicated with sympathizers via “direct mail” channels when the gatekeepers of the “liberal media establishment” refused them access to the established channels of mass communication. The reforms of campaign finance also restricted advertising on radio and television, another factor influencing campaign strategists to focus on “individual mass communication.” The means of communication that are specific to a target group, for example direct mail or email communication, reach the desired audience with considerable precision. Such means are very suitable for mobilizing the (religious) voter base and for raising campaign funds. Another advantage lies in the fact that the targeted messages directed to the groups’ core does not alienate more moderate voters, as had been the case with earlier, diffuse campaigns on TV.

Other channels of communication have also been used in addition to the activities of legions of volunteers going from door to door. The technological development of both parties indicates that not only the traditional direct mail appeals, but also the internet is a theatre of the so-called “ground war.” The internet also serves to tap into previously unexploited financial resources, and the Christian Right is reaping the rewards of its pioneering use of this strategy. Its political treasure-trove of donor lists and electronic databases has not only paid off when selecting a candidate and in intra-party power struggles, but in legislative battles too. In fact, the aforementioned grassroots organizations and interest groups of the Christian Right deserve special attention within the legislative process: the office of the former Republican Majority Leader Tom DeLay has deemed them to be significant.[26]

Impacting Policy-Making

Well-organized, religiously motivated organizations with a significant membership will gain a stronger voice in the chorus of political debate through their efforts to mobilize voters, channel campaign contributions and mobilize support for legislative battles. Advertising campaigns on issues are another important political tool that has an impact on both election campaigns and policy-making.

An especially effective means of influencing the legislative process and re-election are “scorecards” and “voter guides.” For example, the Christian Coalition, the most prominent Christian Right organization, makes a considerable effort to inform its members about the voting behavior of individual members of Congress. Although legal provisions prohibit an explicit identification of the candidate whose name a Christian should or should not tick on the ballot, a voter that is “informed” with the help of a scorecard can draw his or her own conclusions based on a scale from 0% to 100% about someone who was a 100% supporter or even forerunner of the good cause.

This external impact plays a significant role, especially in Congressional elections. Representatives and Senators in the US act like individual entrepreneurs and are not subject to party discipline, but also cannot hide behind it. The individual Congressman is constantly in danger of being attacked during high-profile campaigns and being held personally responsible when running for re-election. Thus, he or she carefully considers how each Congressional vote could affect him or her during the next elections.

The Christian Right organizations have truly mastered the political game. Skillful political professionals have been able to use the Republican Party to entwine the Christian Right’s grassroots organizations and issue networks with the various branches of government, especially the Executive and the Legislative.

Issue Networks

The Religious Right is an “issue network” or “advocacy coalition.”[27] It comprises individuals, organizations and institutions from different fields with common values and problem perceptions, i.e. common worldviews. Among these actors are the Executive, Congress, media, universities, churches, interest groups, grassroots organizations and think tanks. These issue networks or advocacy coalitions can be bipartisan, but can also focus on a partisan agenda. The “issue networks”[28] define and organize themselves politically on the basis of similar interests and political convictions: “True believers” are partisans of “traditional American family values,” thus fighting secularism, feminism and relativism. In the international realm, Evangelicals are eager to make sure that America retains the necessary military means to defend itself and Israel.

It was and remains a particular challenge for party strategists to integrate the Christian Right without jeopardizing cohesion, given that the party’s purpose is to be an umbrella organization for a broad spectrum of Republicans, from those with morally and economically libertarian outlooks to the morally conservative pole. This effort only succeeds when the focus remains on unifying economic and foreign policy, especially national security issues in the fight against terrorism. Domestic culture wars over politically tricky issues such as abortion need to be limited in order not to be counterproductive. There is a consensus among Republicans in favor of reducing the government sector―except for strong national defense. “Defunding the government” is the common denominator: economically libertarian Republicans believe in the unseen hand of the market. For many born-again Christians and devout Evangelicals, personal weaknesses and immoral behavior are the causes of economic failure in this world.

The moral network is thus linked to economic policy: “We also get into tax cuts,” says Jim Backlin, Chief Lobbyist of the Christian Coalition. “That is when we get involved with Grover Norquist.”[29] Norquist, President of Americans for Tax Reform (ATR) and then adviser to George W. Bush’s long-time strategist Karl Rove, organizes a weekly “Wednesday Meeting” in his offices in downtown Washington with 100 to 150 legislative and executive decision-makers, as well as representatives of the aforementioned organizations, to discuss fiscal and foreign policy. The “Lunch Meeting” of the late Paul Weyrich, Chairman and CEO of the Free Congress Foundation, with approximately 70 participants, also takes place on Wednesdays, with moral issues of social policy, national security and other foreign policy themes being on the agenda. The meetings are organized so that participants of one can also attend the other. Norquist’s and Weyrich’s networks operate on the edge of the political playing field, but also become directly involved in the discussions of the central decision-making mechanisms. Conversely, the leading lights of the Legislative and Executive participate in these Wednesday meetings to discuss and brainstorm tactics for pending bills or to discuss the team’s composition for future campaigns and political newcomers from their own ranks.

Policy-making within the legislative branch is also organized through networks of people with similar beliefs or interests. In the US system of checks and balances political parties do not have the same significance as their counterparts in parliamentary systems. Their weakness is institutionally anchored and they have a limited means to recruit staff or formulate policies. There is no strict party discipline. Thus networks, informal groups, so-called caucuses or congressional member organizations have aprominent, central role in the legislative process.[30] Belonging to such groups is an important point of orientation for voters and interest groups, as it enables external actors the possibility to gain influence as opinion leaders and multipliers: “When we need votes,” explains business lobbyist Jeffrey DeBoer, “we don’t have to start from scratch. We have a ready base of support.” Political professionals like to call it “one-stop shopping.”[31] The party leadership also appreciates these groups’ predictability when it comes to gauging support and forging majorities for specific Congressional votes. Caucuses can have a bipartisan impact or strengthen certain alliances within the party.

Congressmen that are moral and fiscal conservatives are very well organized. One of the most influential groups in Congress is the 85-member Republican Study Committee (RSC). Until the mid-1990s, it was headed by the Majority Leader Tom DeLay, in cooperation with Jim Backlin, now the Chief Lobbyist of the Christian Coalition. The group promotes high moral values and considers itself the “conservative conscience” of the Republican Party.[32] The proximity to the leadership in the House of Representatives enables the RSC to play an important role, especially when mediating between economically libertarian, socially liberal,[33] and morally conservative party members.

The morally conservative Representatives, numbering about 40, have joined together in the Value Action Team (VAT). “It was the idea of my boss,” explained Deana Funderburk, who used to be a member of Tom DeLay’s staff, “he asked Mr. Pitts [Representative Joseph Pitts] to coordinate and implement this group. He said, we need to have these outside family groups on the same page and get them together to kind of be a force within the party to push our traditional family values agenda.”[34] In other words, the political leadership in the House of Representatives can muster support at the grassroots level to influence morally-sensitive issues in its favor.

External groups also appreciate this network, which was confirmed by Lori Waters of the Eagle Forum during an interview:

We belong to the Value Action Team. We have been very active in that for a number of years and it is a very effective group, because it takes what is happening inside Congress, activates the members who are socially conservative, and then we get the action plan on the outside as to what to do about what is going on. And we have this good dialogue and communication so that we can more effectively garner support for pro-family issues, socially conservative issues.[35]

The VAT mediates and coordinates the positions of various interest groups, think tanks and other external actors in the legislative process. According to Waters, 30 to 40 organizations regularly participate in this informal network.

The network’s recently established counterpart in the Senate is headed by Senator Sam Brownback.[36] Here, too, likeminded Senators or their senior staff members meet on a weekly basis to coordinate their legislative work with religious interest groups. Senator Sam Brownback and Representative Joseph Pitts regularly compare notes and hold weekly briefings for their respective groups in the Senate and the House about upcoming issues and positions.[37]

The network’s influence reaches all the way to the Senate leadership. “We have a good relationship with former Majority LeaderFrist’s office,” Kristin Hansen, Media Director of the Family Research Council, confirmed, “and he appointed a staff member, who was formerly very instrumental within the Values Action Team, so that indicates to us that Bill Frist recognizes the importance of the social conservatives within the Republican Party.”[38] About one-third of the circles on both sides of the Capitol consist of Congressional staffers and about two-thirds of external, grassroots organizations, interest groups, lobbyists and think tanks.[39]

The Political Road Ahead

It remains a delicate balancing act for Republican strategists to please the Christian Right and to mobilize its potential voters and funding in elections without losing the support of more moderate, morally libertarian Republicans. The Christian Right also has to walk the tightrope to maintain the close alliance with the Republican Party. The pursuit of power requires concessions. In domestic debates, in particular, there is the risk of sacrificing moral principles that were essential during the mobilization of the initial base of support, the pre-requisite for political activities. Christian fundamentalists follow strict dogmas, which allow them to see the world in terms of “good” and “evil”. In the political spectrum, however, compromises need to be found in a pragmatic gray area, which does not accommodate a dichotomous worldview.

39A common denominator in foreign policy is important to enable the creation of a durable electoral coalition. National security issues provide a sustainable platform for different conservative elites and voters, as well as a glue to strengthen the cohesion of a broader Republican majority. Given the terrorist threat, it seems necessary to unite domestically in order to face a foreign enemy. In President Bush’s view, on September 11, 2001 the terrorists attacked the “American way of life,“ a way of life foreseen by the Almighty. To be sure, America feels that it was struck, but it is also well-prepared and certain to defeat “evil” ―under the strong leadership of its President.[40] In some ways reminiscent of Ronald Reagan’s pugnacious declaration against the “Evil Empire” before a group of Evangelicals, George W. Bush has similarly mobilized America to fight against the “Axis of Evil.” Karl Rove, head of strategy and confidant of the President, has been trying hard to establish a permanent Republican majority. Such a structural majority would imply a so-called realignment, an enduring change in the electorate and in voting behavior.[41] In addition to economic and moral issues, it would above all be driven by national security.

40The new threat to America offered an opportunity for the incumbent President to base his election campaigns on his resolute fight against terrorism. National security was the critical issue in the 2002 mid-term elections, in the November 2004 presidential elections, and will continue to have priority in the reasoning of both the electorate and electoral strategists of the Republican Party. Assuming that the fight against terror will continue for a long time, it is probable that Republican campaign strategists and above all the Christian Right will continue their efforts to keep “existential” issues of national security, as well as moral and religious concerns, high on the political agenda. If they succeed, they will determine the basic parameters in the struggle for political power in the United States.

Appendix

Endnotes

- For more detailed information on the denominational categorization, see Lyman Kellstedt and John Green, “Knowing God’s Many People: Denominational Preference and Political Behavior”, in David Leege and Lyman Kellstedt (eds.), Rediscovering the Religious Factor in American Politics, Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1993; Lyman Kellstedt et al., “Grasping the Essentials. The Social Embodiment of Religion and Political Behavior”, in John Green, James L. Guth, Corwin E. Schmidt and Lyman Kellstedt, Religion and the Culture Wars, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

- See Kohut et al., The Diminishing Divide, op. cit..

- In 1987 the percentage was 19%. See Kohut et al., The Diminishing Divide, op. cit., 4.

- See also Geoffrey Layman, The Great Divide: Religious and Cultural Conflict in American Party Politics, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- See Clyde Wilcox, God’sWarriors: The Christian Right in Twentieth-Century America, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992; and Kellstedt et al., “Grasping the Essentials,” op. cit..

- Kohut et al. developed this distinction by adding the aforementioned factors to a total index. See Kohut et al., The Diminishing Divide, op. cit., 164.

- Nicholas Lemann, “The Controller. Karl Rove is Working to Get George Bush Reelected, But He Has Bigger Plans”, New Yorker, May 12, 2003, 81.

- Interview by the author with Gary Bauer, President of American Values, July 22, 2003.

- See Kohut et al., The Diminishing Divide, op. cit., 86.

- See Byron Shafer and William Claggett, The Two Majorities: The Issue Context of Modern American Politics, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995; Geoffrey Layman, “Culture Wars in the American Party System: Religious and Cultural Change among Partisan Activists since 1972”, American Politics Quarterly, vol. 27, 1999, 89-121.

- For further information see James Guth and John Green, The Bible and the Ballot Box: Religion in the 1988 Election, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991; Kevin Phillips, American Dynasty, New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004, Chapter 7, “The American Presidency and the Rise of the Religious Right”, 211-244.

- See John Green, “Murphy Brown Revisited: The Social Issues in the 1992 Election”, in Michael Cromartie, Disciples & Democracy: Religious Conservatives and the Future of American Politics, Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center/Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994, 51.

- See Laurie Goodstein and William Yardley, “Bush Benefits From Efforts to Build a Coalition of Faithful”, New York Times, November 5, 2004.

- See Phillips, American Dynasty, op. cit., 215. See also Green and DiIulio, Evangelicals in Civil Life, op. cit..

- See Green and DiIulio, Evangelicals in Civil Life, op. cit..

- Elisabeth Bumiller, “Evangelicals Sway White House on Human Rights Issues Abroad”, New York Times, October 26, 2003.

- This was John Green’s assessment. See Goodstein and Yardley, “Bush Benefits From Efforts to Build a Coalition of Faithful”, op. cit.. See also the CNN National Exit Poll, <http://www.cnn.com/ELECTION/2004/pages/results/states/US/P/00/epolls.o.html>, accessed on December 7, 2004.

- See Green et al., Murphy Brown Revisited, op. cit., 64.

- The continuous losses of the Democratic Party since the 1960s can be attributed to the disintegration of Roosevelt’s “New Deal Coalition,” especially the shift in orientation among Evangelical Protestant and even some Catholic voters from the Democratic to the Republican Party. This “dealignment” was very pronounced in the South. See Lyman Kellstedt and Mark Noll, “Religion, Voting for President, and Party Identification, 1948-1984”, in Mark Noll, Religion and American Politics: From the Colonial Period to the 1980s,New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- John Green, Mark Rozell and Clyde Wilcox, The Christian Right in American Politics: Marching to the Millennium, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003.

- According to John Persinos, the Christian Right is the dominant faction in 18 state-level Republican Party organizations and a strong faction in 13 other states. See John Persinos, “Has the Christian Right Taken Over the Republican Party?”, Campaigns & Elections, September 1994, 23. See also Mark Rozell and Clyde Wilcox, God at the Grass Roots: The Christian Right in the 1994 Elections, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1995.

- Quoted in Melani McAlister, Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East, 1945-2000, Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2001, 193.

- Translated from Peter Lösche, “Thesen zum amerikanischen Konservatismus”, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B49, December 1982, 37-45, 41.

- Green Rozell and Wilcox, The Christian Right in American Politics, op. cit., 8.

- Anna Greenberg and Jennifer Berktold, “Evangelicals in America, Religion and Ethics”, News Weekly, April 4, 2004, 14.

- Interview by the author with Deana Funderburk, Policy Analyst for then Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX), July 16, 2003.

- For more information on the concept of advocacy coalitions, see Paul Sabatier, “An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein”, Policy Sciences, vol. 21, no. 3, 1988, 129-168; and Paul Sabatier, “Toward Better Theories of the Policy Process”, Political Science & Politics, vol. 24; no. 2; 1991, 147-156. See also Winand Gellner, Ideenagenturen für Politik und Öffentlichkeit: Think Tanks in den USA und in Deutschland, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1995, 26-27.

- See Hugh Heclo, “Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment”, in Samuel Beer and Anthony King, The American Political System, Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1978, 87-124.

- Interview by the author with Jim Backlin, Legislative Director of the Christian Coalition of America, July 16, 2003.

- See Charles Caldwell, “Government by Caucus: Informal Legislative Groups in an Era of Congressional Reform”, Journal of Law and Politics, no. 5, 1989, 625-655.

- Jeffrey DeBoer, President and Chief Operating Officer of the Real Estate Roundtable, quoted in Alan Ota, “Caucuses Bring New Muscle to Legislative Battlefield”, CQ Weekly, September 27, 2003, 2334 ff.

- Alan Ota, “Republican Study Committee Revels in Conservative Clout”, CQ Weekly, September 27, 2003, 2338.

- Grover Norquist, President of the organization Americans for Tax Reform, lobbies very effectively for business-friendly policies and advises Congressional caucuses like the Zero Capital Gains Tax Caucus.

- Interview by the author with Deana Funderburk, Policy Analyst for then Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX), July 16, 2003.

- Interview by the author with Lori Waters, Executive Director, Eagle Forum, July 14, 2003.

- Interview by the author with Cindy Diggs, Legislative Assistant, Representative Joseph Pitts (R-PA), July 17, 2003.

- Interview by the author with Deana Funderburk, Policy Analyst for then Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX), July 16, 2003.

- Interview by the author with Kristin Hansen, Media Director of the Family Research Council (FRC), July 11, 2003.

- This is the assessment of Jim Backlin, chief lobbyist of the Christian Coalition of America during an interview with the author on July 16, 2003.

- “These terrorists kill not merely to end lives but to disrupt and end a way of life“: such was the assessment of President Bush in his speech before Congress on September 20, 2001. See “A Nation Challenged: President Bush’s Address on Terrorism before a Joint Meeting of Congress”, New York Times, September 21, 2001, B4.

- In common usage, the term “realignment“ refers to a lasting phenomenon. Thus, it is only possible to observe such a change with the benefit of hindsight. Nonetheless, one can a priori analyze structural factors that would lead to such a change and point out the potential for a realignment. See James Sundquist, Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1993, 5-6.

Bibliography

- BUMILLER Elisabeth, “Evangelicals Sway White House on Human Rights Issues Abroad”, New York Times, October 26, 2003.

- BUSH George W., “A Nation Challenged: President Bush’s Address on Terrorism before a Joint Meeting of Congress”, New York Times, September 21, 2001, B4.

- CALDWELL Charles, “Government by Caucus: Informal Legislative Groups in an Era of Congressional Reform”, Journal of Law and Politics no. 5, 1989, 625-655.

- CNN NATIONAL EXIT POLL, <http://www.cnn.com/ELECTION/ 2004/pages/results/states/US/P/00/epolls.o.html>, accessed on December 7, 2004.

- GELLNER Winand, Ideenagenturen für Politik und Öffentlichkeit: Think Tanks in den USA und in Deutschland, Opladen: Westdeutscher Verlag, 1995, 26-27.

- GOODSTEIN Laurie and William YARDLEY, “Bush Benefits From Efforts to Build a Coalition of Faithful”, New York Times, November 5, 2004.

- GREEN John, ROZELL Mark and Clyde WILCOX, The Christian Right in American Politics: Marching to the Millennium, Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2003.

- GREEN John and John DIIULIO, Evangelicals in Civil Life: How the Faithful Voted, Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center, January 2001.

- GREEN John, “Murphy Brown Revisited: The Social Issues in the 1992 Election”, in Michael CROMARTIE, Disciples & Democracy: Religious Conservatives and the Future of American Politics, Washington, DC: Ethics and Public Policy Center/Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1994.

- GUTH James and John GREEN, The Bible and the Ballot Box: Religion in the 1988 Election, Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1991.

- GREENBERG Anna and Jennifer BERKTOLD, “Evangelicals in America, Religion and Ethics”, News Weekly, April 4, 2004, 14.

- HECLO Hugh, “Issue Networks and the Executive Establishment”, in Samuel BEER and Anthony KING, The American Political System, Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute, 1978, 87-124.

- KOHUT Andrew, GREEN John, KEETER Scott and Robert C. TOTH, The Diminishing Divide: Religion’s Changing Role in American Politics, Washington, D.C.: Brookings Institution Press, 2000.

- KELLSTEDT Lyman et al., “Grasping the Essentials: The Social Embodiment of Religion and Political Behavior”, in GREEN John, GUTH James L., SCHMIDT Corwin E. and Lyman KELLSTEDT, Religion and the Culture Wars, Lanham, MD: Rowman and Littlefield, 1996.

- KELLSTEDT Lyman and John GREEN, “Knowing God’s Many People: Denominational Preference and Political Behavior”, in David LEEGE and Lyman KELLSTEDT (eds.), Rediscovering the Religious Factor in American Politics, Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1993.

- KELLSTEDT Lyman and Mark NOLL, “Religion, Voting for President, and Party Identification, 1948-1984”, in Mark NOLL, Religion and American Politics: From the Colonial Period to the 1980s,New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1990.

- LAYMAN Geoffrey, The Great Divide: Religious and Cultural Conflict in American Party Politics, New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 2001.

- LAYMAN Geoffrey, “Culture Wars in the American Party System. Religious and Cultural Change among Partisan Activists since 1972”, American Politics Quarterly, vol. 27, 1999, 89-121.

- LEMANN Nicholas, “The Controller: Karl Rove is Working to Get George Bush Reelected, But He Has Bigger Plans”, New Yorker, May 12, 2003.

- LÖSCHE Peter, “Thesen zum amerikanischen Konservatismus”, Aus Politik und Zeitgeschichte, B49, December 1982, 37-45.

- MCALISTER Melani, Epic Encounters: Culture, Media, and U.S. Interests in the Middle East, 1945-2000, Berkeley/Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press, 2001.

- OTA Alan, “Caucuses Bring New Muscle to Legislative Battlefield”, CQ Weekly, September 27, 2003, 2334 ff.

- OTA Alan, “Republican Study Committee Revels in Conservative Clout”, CQ Weekly, September 27, 2003, 2338.

- PEOPLE FOR THE AMERICAN WAY, <http://www.pfaw.org/ pfaw/general/default. aspx?oid=3147>, accessed on December 7, 2004.

- PERSINOS John, “Has the Christian Right Taken Over the Republican Party?”, Campaigns & Elections, September 1994.

- PHILLIPS Kevin, American Dynasty, New York, NY: Penguin Books, 2004.

- ROZELL Mark and Clyde WILCOX, God at the Grass Roots: The Christian Right in the 1994 Elections, Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 1995.

- SABATIER Paul, “Toward Better Theories of the Policy Process”, Political Science & Politics, vol. 24, no. 2, 1991, 147-156.

DOI : 10.1017/S1049096500050630 - SABATIER Paul, “An Advocacy Coalition Framework of Policy Change and the Role of Policy-Oriented Learning Therein”, Policy Sciences, vol. 21, no. 3, 1988, 129-168.

DOI : 10.1007/BF00136406 - SHAFER Byron and William CLAGGETT, The Two Majorities: The Issue Context of Modern American Politics, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995.

- SUNDQUIST James, Dynamics of the Party System: Alignment and Realignment of Political Parties in the United States, Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 1993, 5-6.

- WILCOX Clyde, God’s Warriors: The Christian Right in Twentieth-Century America, Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1992.

Interviews by the author with:

- BACKLIN Jim, Legislative Director of the Christian Coalition of America, July 16, 2003.

- BAUER Gary, President of American Values, July 22, 2003.

- DIGGS Cindy, Legislative Assistant, Representative Joseph Pitts (R-PA), July 17, 2003.

- FUNDERBURK Deana, Policy Analyst for then Majority Leader Tom DeLay (R-TX), July 16, 2003.

- HANSEN Kristin, Media Director of the Family Research Council (FRC), July 11, 2003.

- WATERS Lori, Executive Director, Eagle Forum, July 14, 2003.

Originally published by Revue LISA/LISA e-journal IX-n°2, 2011, DOI:10.4000/lisa.9675, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.