By defining Protestant morality as the foundation of the republic, Social Gospel leaders sought to sanctify the state while narrowing the scope of national identity.

By Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

The Social Gospel Movement emerged in the United States during the late nineteenth century as Protestant ministers and theologians sought to address the upheavals of industrialization, urban poverty, and labor unrest. While it has often been remembered as a humanitarian or reformist movement, the Social Gospel was also profoundly nationalistic. By tying Christian ethics to the destiny of the American state, its leaders articulated a vision of America as a redeemer nation charged with enacting God’s will in the social order. Its reform agenda, from labor rights to temperance, was framed not only as moral duty but as a patriotic mission, reinforcing Protestant norms as synonymous with American identity. The Social Gospel thus functioned as both a theology of reform and a form of Christian nationalism, one that reshaped American politics while narrowing the meaning of national belonging.

Origins of the Social Gospel

Evangelical Protestant Foundations

The Social Gospel drew deeply from the well of evangelical Protestantism. For decades, revivals had emphasized the conversion of the individual soul, urging personal repentance and moral discipline. Yet by the mid-nineteenth century, a shift was underway. The scale of poverty and industrial unrest made individual salvation seem insufficient; ministers began to imagine sin as social as well as personal. Out of this realization emerged a call for collective reformation, a new theology that sought to align Christianity with the pressing realities of an industrial age.

Equally powerful was the postmillennial outlook that infused the movement. Postmillennialists believed that Christ’s kingdom would arrive only after humanity prepared the world for His reign. Social reform was thus an eschatological project. Poverty, injustice, and exploitation were not merely civic problems; they were obstacles to the fulfillment of divine prophecy.1 In this framework, the Social Gospel linked salvation to the nation’s destiny, presenting America as a field upon which God’s purposes would be fulfilled.

Intellectual and Cultural Context

The cultural environment of the Gilded Age magnified the urgency of this theology. Factories and railroads transformed the economy, yet wealth was concentrated in a few hands while millions endured poverty. Urban slums filled with families living in unsanitary and overcrowded conditions, giving visual testimony to the failures of laissez-faire capitalism. To ignore these realities was, for Social Gospelers, to ignore Christ Himself, who identified with “the least of these.”

Labor unrest sharpened the crisis. Strikes and violent clashes between workers and employers suggested that America’s social fabric was fraying. To Protestant leaders, such unrest was not simply a political issue but a symptom of moral failure. The Gospel had to be applied not only in pulpits but in factories and picket lines.2

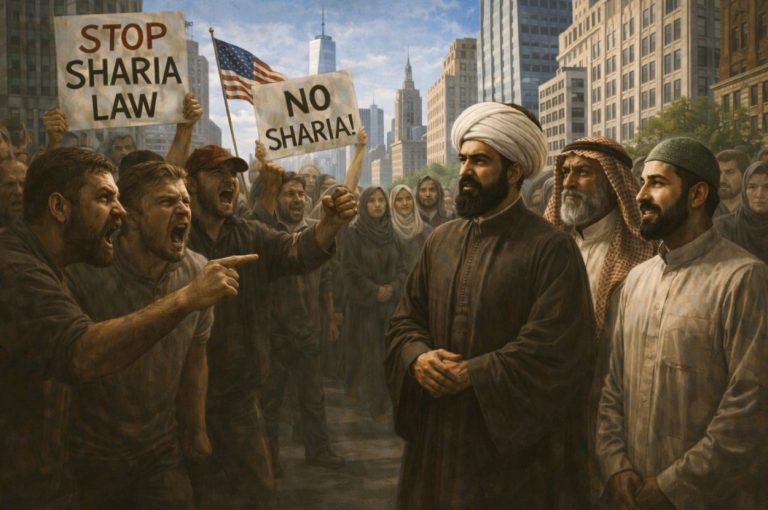

Immigration added yet another dimension. Millions of newcomers arrived from southern and eastern Europe, bringing languages, customs, and religions unfamiliar to the Protestant establishment. While many Social Gospel reformers sought to serve these populations, their impulse was often assimilationist. The immigrant had to be shaped into a citizen, and citizenship itself was imagined as Protestant at its core.

National Identity and Christian Morality

America as a “Redeemer Nation”

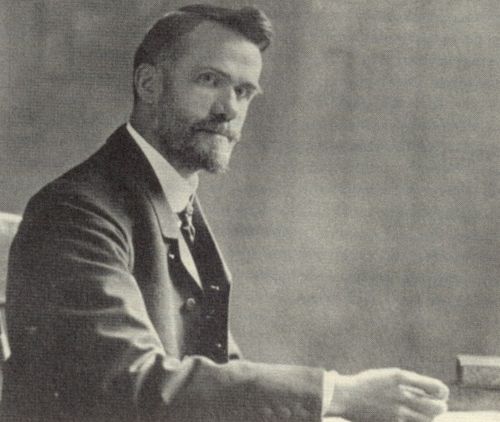

The Social Gospel cast America in explicitly providential terms. Walter Rauschenbusch declared that the nation had a sacred mission: to embody Christian principles in its institutions. He envisioned a society in which the structures of industry, government, and community reflected the justice and compassion of Christ.3 America’s destiny, in this telling, was not merely political but theological.

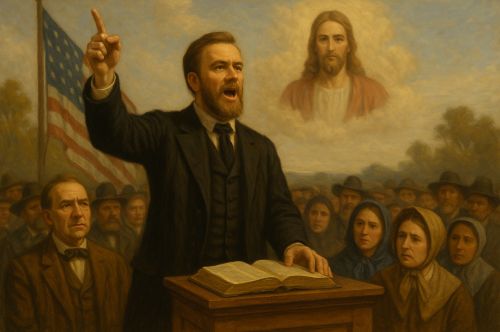

This rhetoric echoed earlier Puritan imagery. John Winthrop’s vision of a “city upon a hill” reappeared in industrial guise, with the United States portrayed as a collective model for humanity. Reform became a form of national witness. To fail in justice was not only a betrayal of Christian duty but of America’s divine calling. The Social Gospel thus fused piety with patriotism, sanctifying the nation as God’s chosen instrument.

Protestant Hegemony

Yet this redeemer vision carried sharp limits. The Social Gospel was almost exclusively a Protestant project, shaped by clergy and theologians from mainline denominations. Catholics and Jews were rarely granted a voice, and their traditions were often depicted as obstacles to national moral progress.4 The language of reform presented Protestant values as if they were universal, quietly excluding other faiths from the national imagination.

Immigrants were welcomed into this vision only if they embraced Protestant norms. Reformers taught English in settlement houses, offered Bible classes, and linked moral improvement with assimilation. Compassion was real, but it came with strings: to be American meant to be Protestant in character. This exclusionary impulse marked the Social Gospel as not only reformist but nationalist in its essence.

Reform as National Theology

Labor and Industry

Few areas reveal the nationalist theology of the Social Gospel more clearly than its engagement with labor. Rauschenbusch and his contemporaries argued that capitalism, as practiced, was a system of structural sin. Poverty was not the fault of individuals but of social arrangements that allowed exploitation. In this sense, the factory floor was a battleground for the soul of the nation. To permit unsafe working conditions or starvation wages was to defile America’s covenant with God.5

The call for reform was therefore both moral and patriotic. Ministers lobbied for legislation protecting workers, advocated for unions, and urged the public to see labor rights as a Christian obligation. By embedding labor reform within national theology, they reframed the conflict between capital and labor as a question of divine justice.

Yet this vision was not without limits. The Social Gospel sometimes romanticized labor as inherently virtuous, while overlooking the complexities of class conflict. Still, its insistence that industry must be held to Christian standards marked a turning point: the nation itself was judged by the conditions of its poorest citizens.

Temperance and Purity Movements

Temperance campaigns revealed another dimension of national theology. Alcohol abuse was portrayed not only as a private vice but as a civic threat. Drunkenness undermined family stability, eroded productivity, and threatened the moral character of the republic. Thus, prohibition became a patriotic project as much as a religious one. To be sober was to be a good citizen.6

Purity movements extended this moral vision into sexuality and family life. Reformers insisted that personal morality was inseparable from civic strength. The nation could not prosper if its citizens were weak, undisciplined, or immoral. This intertwining of private virtue and public health reinforced the nationalist impulse: moral reform was not simply for the individual’s sake but for the survival of the nation itself.

Urban and Immigration Reform

Social Gospelers poured energy into urban reform. Settlement houses, slum missions, and social programs sought to alleviate the harshest realities of city life. These efforts reflected genuine compassion, a desire to embody Christ’s love among the poor. But they also carried an assimilationist agenda. Immigrants were taught not only literacy and hygiene but Protestant values.

In practice, this meant that reform blended charity with cultural coercion. Immigrants were welcomed as Americans-in-the-making, but only if they conformed to Protestant ideals. This paradox revealed the nationalist edge of the Social Gospel: inclusion came at the price of cultural erasure.7

Some reformers recognized the tension, urging more pluralistic approaches, yet the dominant impulse was clear. Reform was as much about shaping America into a Protestant nation as it was about alleviating poverty.

Christian Nationalist Dimensions

Fusion of Piety and Patriotism

The Social Gospel fused the language of faith with the language of patriotism. Sermons urged congregants to see reform not only as Christian duty but as loyalty to the republic. In this sense, the nation itself was sacralized, its destiny tied to the realization of Christian ethics. The pulpit became a platform for both revival and nationalism, blending altar and flag.8

This fusion gave reform campaigns extraordinary rhetorical power. To oppose labor laws or prohibition was to oppose not only reformers but God’s will for the nation. By casting social justice as national destiny, the Social Gospel blurred distinctions between religious mission and civic identity.

National Moral Authority

The movement also sought to reshape legislation, advocating for child labor bans, antitrust regulations, and prohibition laws. Ministers urged lawmakers to legislate Protestant ethics, portraying the state as God’s instrument for justice. In doing so, they blurred the lines between church and state. Reform was not merely an option for Christians but a national obligation for lawmakers.9

Critics accused the Social Gospel of politicizing religion, but its leaders saw no contradiction. For them, the health of the nation depended on aligning civil law with divine law. This was Christian nationalism in practice, enshrined in public policy.

Limits and Exclusions

Despite its lofty rhetoric, the Social Gospel often ignored racial injustice. African Americans, facing systemic segregation and violence, rarely appeared in its vision of reform. The “nation” being redeemed was imagined as white, Protestant, and patriarchal.10

Women, though active at the grassroots, were often sidelined from leadership. Their reform efforts were praised, yet the national stage remained dominated by male ministers. This exclusion reinforced the very hierarchies the movement claimed to challenge. The Social Gospel’s nationalism was thus selective, promising redemption while narrowing the boundaries of citizenship.

Legacy and Critique

Long-Term Influence

The Social Gospel left an indelible mark on American reform. Progressive Era legislation addressing child labor, sanitation, and public health drew inspiration from its theology. By framing reform as moral necessity, the movement legitimized government intervention in areas previously considered private or economic.11

Theological Contributions

Beyond politics, the Social Gospel reshaped theology. Its emphasis on structural sin influenced later Christian ethics, including Catholic social teaching and Protestant engagement with the New Deal. The idea that social arrangements could themselves be sinful challenged individualistic understandings of morality.

Seeds of Christian Nationalism

Yet the Social Gospel also planted the seeds of later Christian nationalism. By equating Protestant morality with American identity, it normalized the blending of religion and politics. Even as its influence waned, the assumption that America’s laws should reflect Christian ethics endured.12 Its paradoxical legacy was thus twofold: it humanized capitalism and advanced justice, yet it also reinforced exclusionary visions of the nation.

Conclusion

The Social Gospel Movement was born of a desire to apply Christian principles to the crises of industrial America. Yet it was also more than a theology of reform: it was a nationalist project that imagined America as God’s chosen nation. By defining Protestant morality as the foundation of the republic, its leaders sought to sanctify the state while narrowing the scope of national identity.

Its legacy is dual, inspiring reforms that alleviated suffering, but also perpetuating a vision of America as a Protestant nation. As such, the Social Gospel illustrates how Christian reform could simultaneously serve as humanitarian endeavor and instrument of Christian nationalism.

Appendix

Footnotes

- Walter Rauschenbusch, Christianity and the Social Crisis (New York: Macmillan, 1907), 63–67.

- Christopher H. Evans, The Social Gospel in American Religion (New York: NYU Press, 2017), 29–34.

- Rauschenbusch, Christianity and the Social Crisis, 85–91.

- Robert T. Handy, A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities (New York: Oxford University Press, 1971), 111–115.

- Gary Dorrien, Social Ethics in the Making: Interpreting an American Tradition (Malden: Blackwell, 2009), 87–93.

- Susan Curtis, A Consuming Faith: The Social Gospel and Modern American Culture (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991), 144–149.

- Evans, The Social Gospel in American Religion, 57–62.

- Ronald C. White and C. Howard Hopkins, The Social Gospel: Religion and Reform in Changing America (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1976), 205–210.

- Handy, A Christian America, 119–124.

- Curtis, A Consuming Faith, 172–178.

- Dorrien, Social Ethics in the Making, 101–106.

- Evans, The Social Gospel in American Religion, 198–203.

Bibliography

- Curtis, Susan. A Consuming Faith: The Social Gospel and Modern American Culture. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1991.

- Dorrien, Gary. Social Ethics in the Making: Interpreting an American Tradition. Malden: Blackwell, 2009.

- Evans, Christopher H. The Social Gospel in American Religion. New York: NYU Press, 2017.

- Handy, Robert T. A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

- Rauschenbusch, Walter. Christianity and the Social Crisis. New York: Macmillan, 1907.

- White, Ronald C., and C. Howard Hopkins. The Social Gospel: Religion and Reform in Changing America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1976.

Originally published by Brewminate, 08.29.2025, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.