How Americans decide what ‘news’ means to them.

Measuring people’s news habits and attitudes has long been a key part of Pew Research Center’s efforts to understand American society. Our surveys regularly ask Americans how closely they are following the news, where they get their news and how much they trust the news they see.

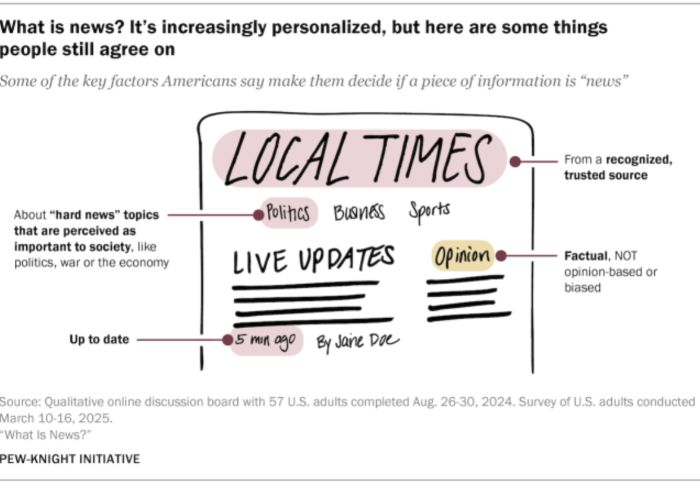

But as people are exposed to more information from more sources than ever before and lines blur between entertainment, commentary and other types of content, these questions are not as straightforward as they once were. This unique study from the Pew-Knight Initiative explores the question: What is “news” to Americans – and what isn’t?

Before the rise of digital and social media, researchers had long approached the question of what news is from the journalist perspective. Ideas of news were often tied to the institution of journalism, and journalists defined news and determined what was newsworthy. “News” was considered information produced and packaged within news organizations for a passive audience, with emphasis (particularly in the United States) placed on a particular tone, a set of values and the idea of journalism playing a civic role in promoting an informed public.

In the digital age, researchers – including Pew Research Center – increasingly study news from the audience perspective, what some have deemed an “audience turn.” Using this approach, the concept of news is not necessarily tied to professional journalism, and audiences, rather than journalists, determine what is news.

The results of this study capture these changing dynamics of news consumption in the U.S. The journalists and editors we interviewed agree that in the digital age, the power to define news has largely shifted from media gatekeepers to the general public. And discussions with everyday Americans confirm the idea that its definition varies greatly from person to person, with each bringing their own mindset and approach to navigating a dizzying information environment.

These perceptions are consequential because news – regardless of what people consider it to be – remains a consistent part of most Americans’ lives today. About three-quarters of U.S. adults (77%) say they follow the news at least some of the time, and 44% say they intentionally seek out news extremely often or often. This study provides a deeper understanding of what “news” means to Americans and how they decide where to turn for it.

Key findings:

- Defining news has become a personal, and personalized, experience. People decide what news means to them and which sources they turn to based on a variety of factors, including their own identities and interests.

- Most people agree that information must be factual, up to date and important to society to be considered news. Personal importance or relevance also came up often, both in participants’ own words and in their actual behaviors.

- “Hard news” stories about politics and war continue to be what people most clearly think of as news. U.S. adults are most likely to say election updates (66%) and information about the war in Gaza (62%) are “definitely news.”

- There are also consistent views on what news is not. People make clear distinctions between news versus entertainment and news versus opinion.

- At the same time, views of news as not being “biased” or “opinionated” can conflict with people’s actual behaviors and preferences. For instance, 55% of Americans believe it’s at least somewhat important that their news sources share their political views.

- People don’t always like news, but they say they need it: While many express negative emotions surrounding news (such as anger or sadness), they also say it helps them feel informed or feel that they “need” to keep up with it.

- People’s emotions about news are at times tied to broader feelings of media distrust, or specific events going on at that time – perhaps in combination with individuals’ political identities. For instance, partisans often react positively to news about their own political parties or candidates and negatively to news covering their opposition, which means feelings can shift with political changes.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT PEW RESEARCH CENTER