By Dr. Tom Garlinghouse

Archaeologist/Anthropologist

Bipedality, the ability to walk upright on two legs, is a hallmark of human evolution. Many primates can stand up and walk around for short periods of time, but only humans use this posture for their primary mode of locomotion.

Fossils suggests that bipedality may have begun as early as 6 million years ago. But it was with Australopithecus, an early hominin who evolved in southern and eastern Africa between 4 and 2 million years ago, that our ancestors took their first steps as committed bipeds. Yet scientists still know little about the circumstances that led to this trait’s emergence.

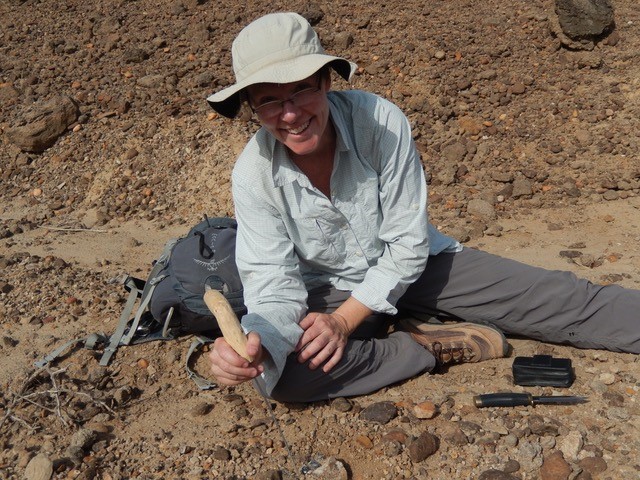

Carol Ward, a paleoanthropologist and anatomist at the University of Missouri, studies this question. A specialist in human origins, Ward has spent a number of field seasons at various paleontological sites, including at Kanapoi and Lomekwi in West Turkana, Kenya, where she and her colleagues recovered australopithecine fossils. Her latest work repurposes 3D medical-imaging technologies to compare modern primate anatomy, including soft tissues and organs, with the skeletal fossil record of ancient hominids. That technique allows her to make inferences about our ancient ancestors and how their bodies supported different forms of locomotion. As she discussed in a short lecture at the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS) annual meeting in Washington, D.C., in February, figuring out how and why humans became bipedal could be essential to understanding human evolution more broadly.

The following conversation with Ward has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Let’s start with the basics. Will you please explain bipedality in layperson’s terms and why it’s such an important concept in human evolution?

The way that humans get around the world is different from any other animal on Earth. We move around on the ground, upright on two feet, but in a unique way: with one foot after the other, holding our body fully upright in a characteristic series of motions. This is something that no other primate does, and it seems to be a behavior that was present in some of the earliest members of our branch of the family tree. It represented what was really the initial major adaptive change from any apelike creature that came before us. So it’s a big deal to figure out how and why we walk the way we do, in order to figure out why and how our lineage really diverged so much from apelike creatures.

Which step was more important in our evolution: bigger brains or bipedality?

Clearly, what is the most unusual, distinctive feature of humans today is our incredible and amazing brain. Our brains can do things that other animals on this planet have never even come close to doing. It gives us culture and language—and all those things that really make us distinctive today as a species. But the fossil record tells us that we began to walk upright on two feet maybe between 6 and 4 million years ago. Brains in early hominins really don’t start to get large until after 2 million years ago, so for the first two-thirds of human evolution, brain size change wasn’t really a major event.

The transition to bipedality is poorly understood. Why?

It’s partially because of the fossil record. We have many apelike creatures that lived in the Miocene, between 23 and 5 million years ago. There’s nothing really like us at this time. And then there’s a gap in the fossil record, largely because of geologic happenstance, if you will. There aren’t many sites at the right time and place that have any fossils. And then all of a sudden, around 4 million years ago, we have these committed bipedal animals, and we don’t have a great fossil record of transitional forms.

That said, sometime between 7 and 4 million years ago a number of primates appear to have developed upright postures, but nothing as developed or specialized as we see later on. So we may be starting to get a little window on this time period.

Can you tell us more about the fossil record from 7 to 4 million years ago?

Absolutely! We have quite a number of apes that preceded the split between chimps and humans. Sahelanthropus is from Chad; it’s about 6 or 7 million years old and is known only from one cranium. Orrorin is known from a thigh bone, a finger bone, and a few teeth. It’s from Kenya, at about 6 million years old. And then there’s this thing called Ardipithecus, which is known from a lot of skeletal elements—skulls and all kinds of things. It’s probably between approximately 5.5 and 4.5 million years old. And it seems to be related to australopithecines and humans but is not a specialized, committed biped. It has a grasping big toe. So it didn’t really give up its tree-climbing ability, which is one thing that australopithecines did do.

In your lecture at the 2019 AAAS annual meeting, you talked about the importance of understanding how the torso is constructed in primates and how the torso can impede or facilitate upright walking. How do you study that feature?

Limb bones tend to be pretty sturdy and they fossilize pretty well, so we have a lot more limb-bone elements in the fossil record than torso elements, such as ribs and vertebrae. They tend to be pretty fragile bones. Also, they receive very little attention because the torso is made up of a lot of bones that aren’t preserved together—they aren’t stuck together. So it’s hard to get a picture of the whole.

CT scanning technologies have been a great help in this regard. We can look at the overall shape, and we can test all these old hypotheses we’ve had about the relationship between locomotion and body shape. That’s what I’ve been doing in my lab over the last 10 or 15 years. We’re getting some cool, new technologies. We are now going to be able to look at muscles and muscle fibers in 3D, and to strap those on the skeleton and really test some ideas.

Can you tell us more about that technology? How does it aid your research?

No longer are we solely looking at, say, a bunch of isolated ribs in the drawer of a museum. With this new technology, we can look at all those bones in articulation (or connected), as they would be in life. We can see how they fit together and how they reflect body shape. By repurposing medical-imaging techniques, we can also look at soft tissues in living primate species to see muscle fibers and things. Every time you look at bones, they’re only useful because they tell you how the muscles are strapped on, but you need to know something about the nerves and circulation—and how all these fit with behavior. We’re beginning to do that now with all these imaging technologies, which is really fun.

If you go to your physician with appendicitis, a head injury, or a bad back, your physician will use CT or MRI scans to diagnose you. We’re taking advantage of the same technology, except we’re CT scanning primate cadavers. That technology has been there for a while already, but now it’s getting easier to use and more affordable.

But some of these new technologies that are being developed are amazing. For example, you can soak tissues in high-contrast solution, like potassium iodine, and visualize soft tissues using CT technology. And then, when you know what the muscles look like, you can put the whole thing together and model it. So when you find a fossil that has a bump or a knob at a different angle, then you can relate it back to how the whole animal is put together with the soft tissues and say something that’s more intelligent and well-informed.

How does this new research challenge some of the long-held notions of our understanding of human evolution?

Taking my perspective in looking at the torso, combined with the new things we’re learning about australopithecines, we are finding out they’re not quite as chimp-like in all ways as we thought. Dipping further back in time, into the ape fossil record, we are finding out those things aren’t very much like modern chimps either. You map that onto the whole tree and apply the basic principles of parsimony (what’s the simplest way this could have happened?), and it’s really supporting the hypothesis that’s been around for a long time: that maybe we didn’t evolve from something that was just like a modern chimp or gorilla. But now we’re able to show in which ways ancient hominids might have been similar or different. And that’s going to help us get a much better picture of what the ancestral condition was that led to bipedality.

Natural selection can only work on “last year’s model.” If you want to understand why something happened, you need to understand what happened.

Originally published by SAPIENS, 05.29.2019, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.