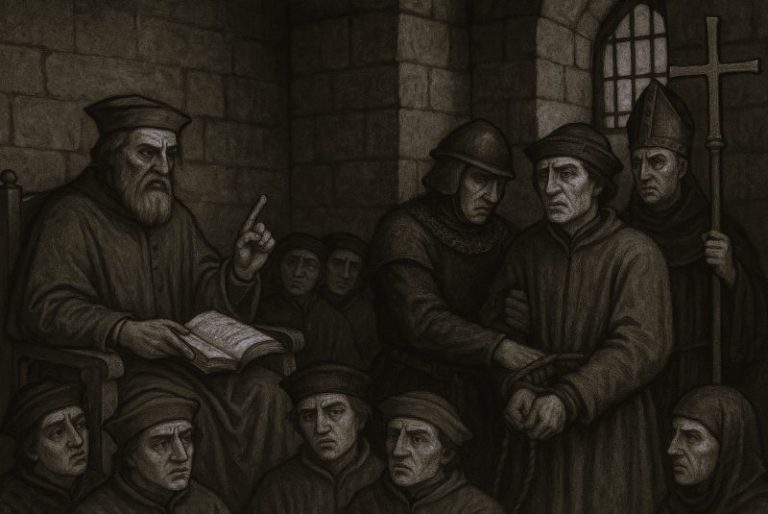

Christian nationalist violence has experienced a resurgence in recent years.

By Dr. Nilay Saiya

Professor of Public Policy and Global Affairs

Nanyang Technological University

Troubling new details regarding the violent propensity of Christian nationalism have been revealed by a new survey on American Christian nationalism released last month. According to the PRRI/Brookings Institution data, adherents of Christian nationalism are almost seven times as likely as those who reject it to support political violence. A stunning 40 percent of Christian nationalism supporters believe that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.”

The revelations of the survey do not bode well for the future of Christian nationalist violence in America. Over the past decade, I’ve analyzed hundreds of religious militant groups around the world. My studies have consistently found that the tipping point toward violence occurs primarily when religious identity and national identity become intertwined. As these identities fuse, historically and culturally dominant faith communities come to see themselves as the victims of encroachment by minority faith traditions. This perceived victimization results in a “persecution complex,” with little regard for the degree of historical or cultural dominance the community enjoys. What matters is that majoritarian religious communities feel like they’re victims.

Perceived victimization often stems from changing religious landscapes, like the unprecedented rise of “the nones” in the US. This new pluralism is seen as threatening to the privileged station of the majority religious tradition, often prompting the self-segregation of majority communities from the rest of society. The resulting echo chamber further reinforces the paranoia surrounding the victim narrative.

Increasingly, members of religious majorities see violence as an acceptable way to beat back the threat posed by religious heterogeneity. Whereas religious violence is commonly believed to be a “weapon of the weak,” it’s actually more often a “weapon of the strong” wielded against marginalized and oppressed minority communities. We see evidence supportive of this thesis in countries as diverse as Brazil, Central African Republic, Pakistan, India, and Myanmar, where vigilantes from dominant religious communities routinely attack the homes, businesses, and houses of worship of religious minorities with impunity.

READ ENTIRE ARTICLE AT RELIGION DISPATCHES