By Suzy Hansen

The neighborhood of Bebek, in Istanbul, is a former fishing village nestled within one of the most picturesque bays of the Bosporus. In October I visited the seashore, where hotel bars and teahouses line the bank; fine-boned, finely dressed people sat and smoked and watched tankers go by. In the fall, the salmon-gold light over the water was so beautiful that it was easy to forget I was in a country where darkness is descending everywhere.

Murat Yetkin, a 59-year-old journalist, had snagged us a waterside table, where he was drinking tea and writing in a notebook. He was just finishing his sixth book of nonfiction, A Book About Spies for the Curious. A week earlier, he had resigned from his job as editor of the Hürriyet Daily News, the English-language arm of Hürriyet, one of Turkey’s largest and most important dailies. “At least we experienced what it meant to be a journalist,” Yetkin said. “I feel sorry for these young people who could not and cannot.” Hürriyet was one of the many Turkish newspapers recently purchased and summarily dismantled by the most prominent family in Turkish media, the Demirörens.

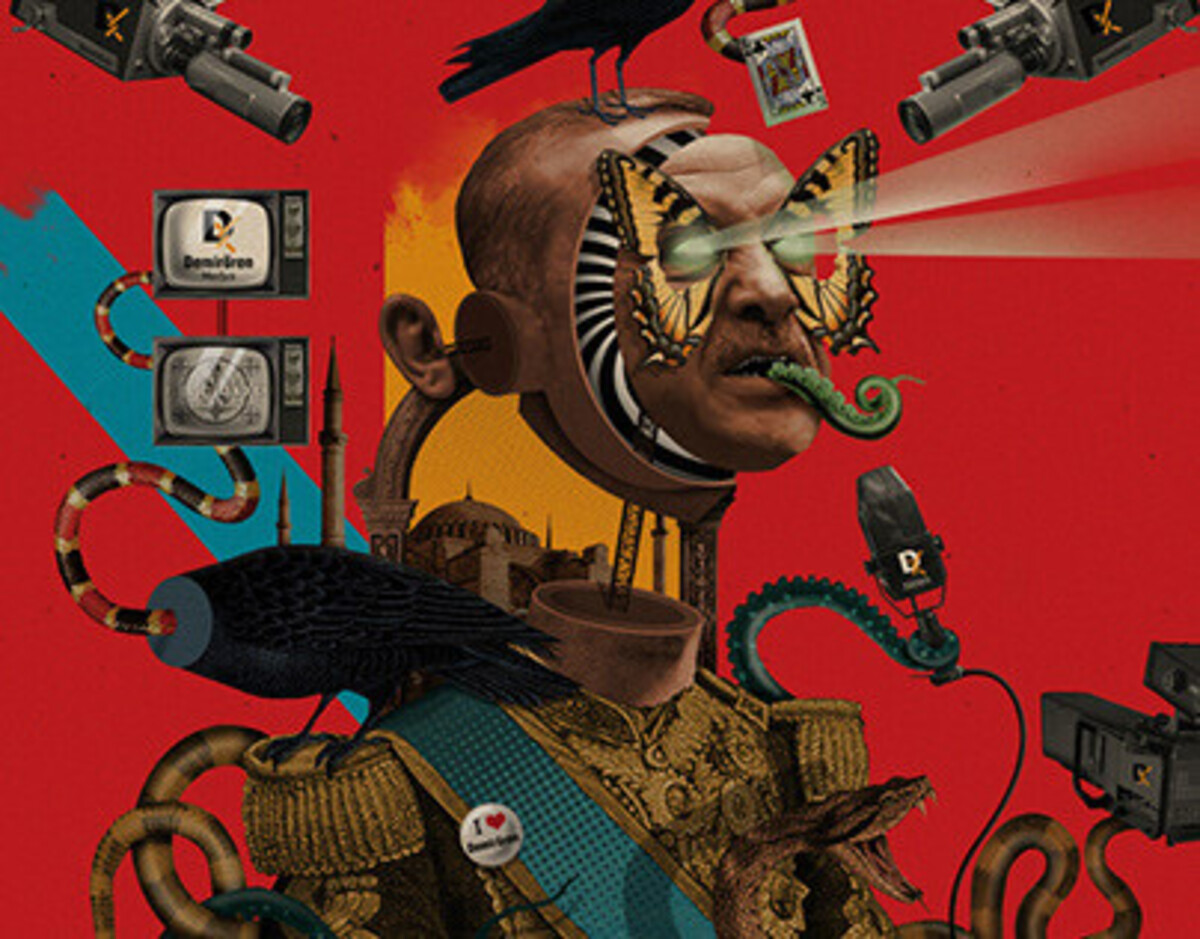

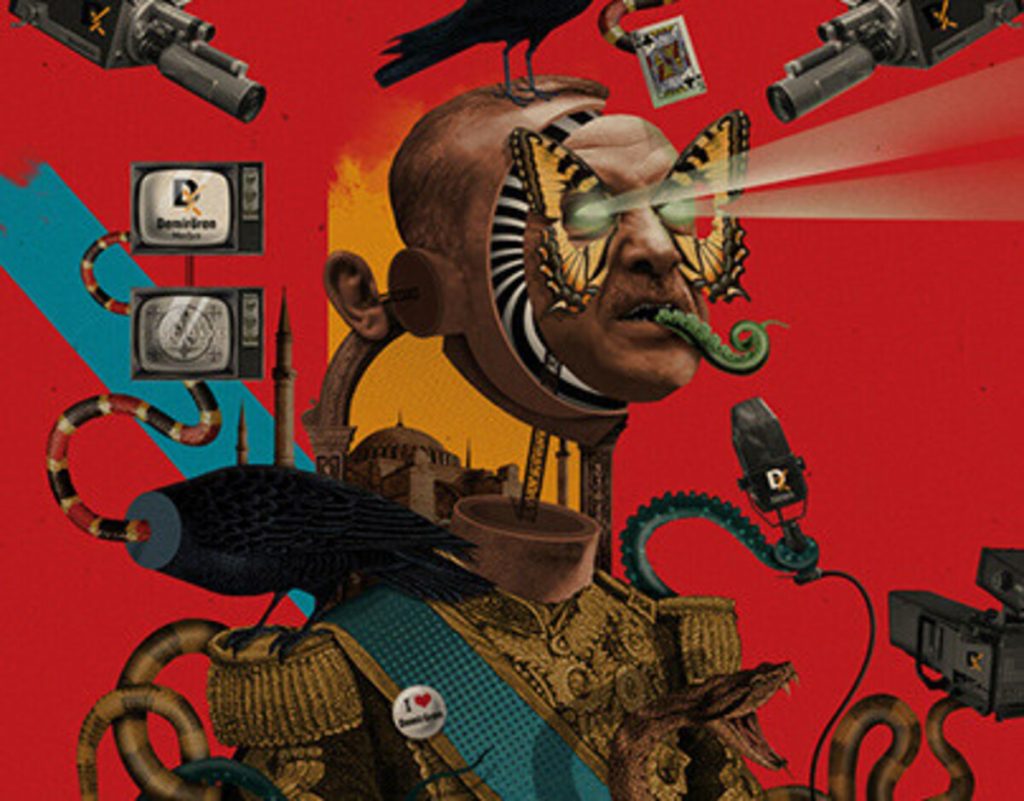

In the past seven years, the Demirörens have come to oversee about a third of Turkey’s media outlets, including one of Turkey’s most watched TV stations, CNN Türk. The family had been involved in newspapers on and off since the seventies, but it wasn’t until a recent antidemocratic scandal that their name became internationally recognized. Last March, the man who was once Turkey’s most powerful newspaper owner, Aydın Doğan, announced that he would sell off his flagship paper and several other entities to the Demirörens, staunch supporters of President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The sale was universally regarded as the Turkish media’s final gasp, mostly because everyone knew that the only reason it could have happened was that Erdoğan wanted it to. Newspapers began referring to Erdoğan Demirören, the family patriarch, as Turkey’s Rupert Murdoch.

But that moniker misrepresents how much Erdoğan, an Islamic conservative, has transformed Turkey’s media since seizing power, and how much he has remade Turkey as a whole. The Murdochs, especially in the age of Donald Trump, are kingmakers; Erdoğan would never permit anyone else to have that much influence. Instead, the Demirören family has become something far stranger, and far more emblematic of the Erdoğan era. As an academic (who asked not to be named because of a pending court case) explained to me, “The Demirörens did not get into the media business on their own—they found themselves compelled to get into it.” In essence, the Demirörens work for Erdoğan. In Turkey, the only kingmaker is the king.

Yetkin—bespectacled, preppy, and mirthful in spite of our depressing topic of discussion—was the most recent casualty of a particularly bloody interval of high-profile firings and resignations at Demirören media organs. He had spent the aughts—a heyday for Turkish journalism—as Ankara bureau chief at Radikal, one of Turkey’s most progressive newspapers. Hürriyet and Radikal were like the New York Times and the Washington Post of Turkey, and there used to be lots of competition: when I moved to Istanbul, in 2007, I marveled at the diversity of the national newspapers piled up at supermarkets—Milliyet, Sabah, Zaman, Cumhuriyet, Star, Akşam, BirGün, Habertürk, Vatan, Sözcü, Posta, Yeni Şafak, Türkiye—a sight all the more striking given the declining number of publications in the United States. They represented a range of political beliefs and rhetorical styles, from serious, even academic journalism to raucous tabloids with half-naked women on the front page.

But around 2008, after Erdoğan won his second term, the Turkish media became the first sacrificial victim of his deepening authoritarianism. In the years since, the most vocal and talented journalists at these papers have been put on trial, thrown in jail, or chased out of the country. (The Committee to Protect Journalists found that 69 Turkish journalists were jailed in 2018, but previous years had seen that number shoot into the hundreds.) Reporters have been hounded and harassed on social media; sometimes they have been arrested for their tweets. They have been forced to censor themselves. They have been left careerless. They have feared for their lives. And they have watched their profession become a farce.