By Dr. Justin Fisher

Professor of Political Science

Brunel University London

Introduction

Magna Carta is a cornerstone of the individual liberties that we enjoy, and it presents an ongoing challenge to arbitrary rule. But over time, while not envisaged at the time of its drafting, Magna Carta has for many been seen not only as a foundation of liberty, but also one of democracy. And this broader notion of the wider significance of Magna Carta makes it especially relevant today. It is perhaps easiest to think of Magna Carta in two ways: first, as a document of historical and legal significance; and secondly, as a principle underlying how we live, through equality under the rule of law and through accountability. Magna Carta matters both for what it said in 1215 and, perhaps more significantly now, for what it has come to symbolise.

Magna Carta as a Source of Liberty

The continuing importance of Magna Carta as a source of liberty is well established. One of the key provisions in the 1215 Charter was that imprisonment should not occur without due legal process. This also established the idea of trial by jury. Clause 39 of the 1215 Charter states that: ‘No free man shall be arrested or imprisoned … or exiled or in any way ruined … except by lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.’ This effectively established the principle of the rule of law, protecting individuals from arbitrary punishment. Of course, that’s not to say all men were therefore free – the feudal system of the time saw to that. But, as with many aspects of Magna Carta, it’s what this principle subsequently helped inspire that makes the Great Charter still relevant today.

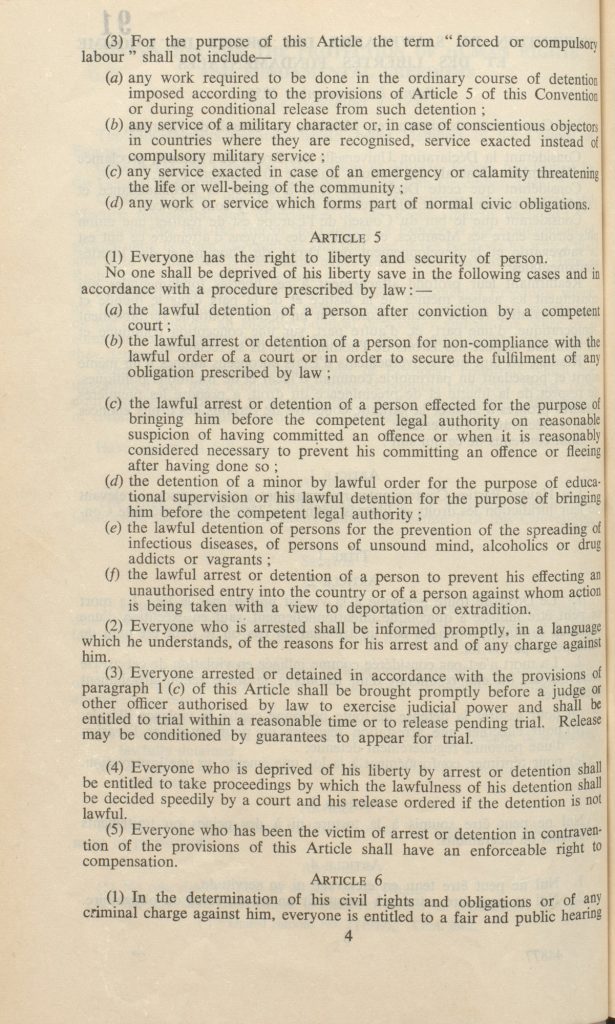

From this principle of the rule of law and equality before the law comes the inspiration for declarations of human rights. Historically, we can point to the Bill of Rights of 1689 in Britain, the Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789 in France, and the Bill of Rights in the United States in 1791. In the 20th century, there were many further examples. Most famous, of course, is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) adopted in 1948, and in 1951, Britain was the first signatory to the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). And, while British parliamentarians, draughtsmen and judges have long taken account of the European Convention, it was finally incorporated into British law with the Human Rights Act of 1998.

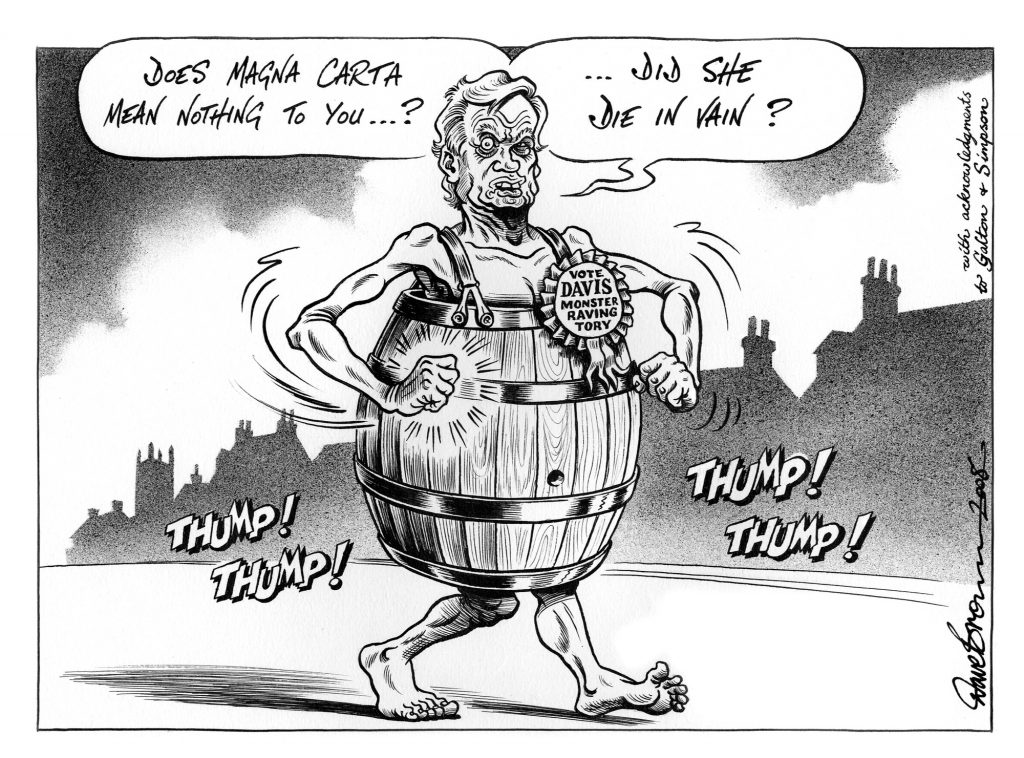

Magna Carta was not as broad in scope as any of these. But the key is that the ideas rooted in Magna Carta were an inspiration for them. So while many clauses of Magna Carta seem irrelevant now and indeed the vast majority are no longer on the statute book, it is not an exaggeration to suggest that Magna Carta forms the basis of the freedoms and liberties we now enjoy. Of course, abuses of these principles may still occur. Critics point to attempts in the early 2000s to extend the period of detention without trial as a response to heightened concerns over terrorism. But citizens in Britain are, compared with many others, rarely subject to abuses of their human rights – a liberty first established through Magna Carta.

Magna Carta’s Broader Relevance

Just as with the principles of liberty, the continuing importance of Magna Carta may also be found in its broader ideas as they have been reinterpreted over the centuries. From these, Magna Carta can also be seen as a foundation of accountability, of popular democracy, and even of the importance of engaged citizens. The fact that Magna Carta had precious little (if indeed anything at all) to say about these things is to miss the point. Historians have shown that, over time, different generations reinterpreted Magna Carta’s meaning to match the dominant ideas of their age.

Democracy, for example, was not linked with the concept of liberty until at least the time of the English Civil Wars. Thinkers began to posit the idea that liberty under the rule of law may well depend on a wider involvement in the creation of that law. And for that to occur, institutions like Parliament would need to develop and include more citizens both as members and electors. Of course, that process took a great deal of time and, indeed, we might argue that it is still developing, with live debates about the extension of the franchise to prisoners and those aged 16 and above. But the important point here is that Magna Carta’s meaning was reinterpreted, so that the contemporary relevance goes well beyond the original intention, not only in the embedding of human rights into our statute book, but also seeing liberty as a fundamental cornerstone and foundation for democracy. But with that comes potential conflict between the principles of liberty and those of democracy.

As these ideas developed, they began to reveal a central tension in the idea of liberal democracy. Magna Carta was fundamentally about the law being pre-eminent, and in the context of arbitrary rule by a monarch, that made good sense. But as the sovereignty of the elected Parliament developed after 1688, then the question of the balance of power inevitably arose. Should a sovereign parliament be free to repeal laws reflecting the will of the people, or should it be constrained by the law. In other words, was popular sovereignty through Parliament a better guarantor of liberties?

From the 19th century onwards, it became clear in Britain that this emphasis was shifting towards Parliament, with many provisions of Magna Carta deleted from the statute book as they were considered obsolete. And the British were often seemingly comfortable with the principles of democratic sovereignty, seeing them as more flexible in dealing with emergencies, such as uprisings or wars, while the general principles of personal liberty were seen as being maintained. General Elections, for example, were suspended during World War Two. If the will of the people demanded restrictions on dangerous groups or individuals, then that was surely preferable to the rigidity of an unbending law?

Yet, of course, even democratically elected governments drawing on the will of the people can be tyrannical, or at least be perceived as a threat to individual liberties. In Britain, this perception started to grow in the mid-1960s, particularly with concerns that Parliament was increasingly unable to control the executive. But this tension between democracy and liberty is heightened with the increasing involvement of the judiciary. Advocates of parliamentary sovereignty argue that the principle of liberty being above that of democracy politicises unelected and unaccountable judges. Can it be right, they argue, that the will of the people exercised through a democratically elected parliament can be struck down by an unelected judge?

Such questions become even more pertinent as definitions of human rights become increasingly broad, since inevitably those declarations may be flavoured by the political fashions of the day. The French Declaration of the Rights of Man and the Citizen of 1789, for example, includes an article citing the basis upon which tax should be raised – equally apportioned among all citizens according to their means. Yet such a principle would almost certainly not find favour across the political spectrum today. More recently, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), alongside relatively uncontroversial human rights such as that to life and the prohibition of torture, also includes the right to marriage (though not to same sex marriage). Not only does breadth throw up some curious notions of human rights, it is also more likely to lead to clashes between individuals and groups, both claiming rights.

On the one hand, for example, the ECHR guarantees the freedom of religion manifested through observance and practice, subject to certain restrictions in accordance with the law. On the other hand, the Convention prohibits discrimination. And, in recent years, the British Supreme Court has had to adjudicate precisely on such a clash, where a practising Christian couple refused to allow a gay couple to stay in their bed and breakfast accommodation. Both parties claimed that their human rights were threatened. Of course, the vast majority of religious observance does not impinge upon anyone else’s rights, but this example illustrates how liberties themselves can be in conflict with each other.

Even supposedly uncontroversial human rights may also prove to be controversial. The ECHR prohibits the death penalty except in relation to war. Yet the will of the people, if we take public opinion polls as our guide, has consistently supported the restoration of capital punishment in Britain. Interestingly, the issue periodically re-surfaces in Parliament, but MPs have proven to be effective guarantors of rights through consistently voting down attempts to reintroduce the death penalty.

Debates about liberty and the sovereignty of the democratically elected Parliament have been brought into sharp relief over the last forty or so years in respect of governments’ attempts to deal with the increased threats of terrorism. And, indeed, both major parties have had cause to seek to assert parliamentary sovereignty. While in power, the last Labour government found itself in conflict over the detention of terror suspects and matters like immigration. Equally, at the last election, the Conservatives pledged to repeal the Human Rights Act (1998) and replace it with a ‘more flexible’ British Bill of Rights. More recently, some in the Conservative Party have called for the withdrawal of Britain from the ECHR altogether, when faced with difficulties over the extradition of foreign criminals. Most recently, the threat from terrorism has prompted government to contemplate challenging the right to privacy through allowing the intelligence services access to individuals’ emails and electronic communications. In a 2015 poll on this topic by YouGov, 53% were broadly in favour of the government’s position.

So, Magna Carta continues to be of great relevance to us all. It is the foundation of liberty and arguably, ultimately, of democracy. But, as we have seen, parliamentary democracy may bring with it challenges to liberties through reflecting the will of the people and aspirations of politicians. All of these issues are live and ongoing and provide rich areas for debate. So let’s not think about Magna Carta solely in terms of medieval and legal history. Those aspects are obviously important. But perhaps most important is what Magna Carta has come to symbolise, even though this was almost certainly not what was envisaged or intended by those who drafted the Great Charter 800 years ago.

Originally published by the British Library, 03.12.2015, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.