The place of whiteness in past understandings of sunstroke and mental illness.

By Dr. Kristin D. Hussey

Historian, Curator, Author and Communicator

Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Medical Museion and Novo Nordisk Foundation Center for Basic Metabolic Research (CBMR), University of Copenhagen

Introduction

On 26 May 1873, at a pub just outside Paddington Station, an inquest was held into the death of Major Edward Ripley. In Victorian London, it was common for inquests to be held as close as possible to the scene of the incident. The main witness was Dr Thomas Christie, the superintendent of the nearby Royal India Asylum in Ealing, where Ripley had been a patient.

Christie told the crowd that Ripley had been under his care for a case of “general mania” caused by “exposure to the sun in India”. Having recently been released, Ripley had returned for a short checkup. On 22 May he had left the asylum on the morning train, travelled to New Bond Street and bought a gun. Returning to Paddington Station, he had shot himself in the head on the platform. The jury returned a verdict of suicide while in a state of unsound mind.

Ripley’s story tells us something about the intersections of imperialism, whiteness and mental illness at the height of the British Empire. While such a desperate act and sad ending may seem exceptional, it was extremely commonplace among white working-class men circulating between Britain and India in the 1800s.

Victorian newspapers are filled with stories of soldiers from India taking their own lives or committing violent crimes. The cause? Sunstroke insanity. Or so the doctors said.

If you’ve never heard of sunstroke insanity, it’s because this diagnosis was only used in the last decades of the 19th century. It was one of a number of pathological conditions created at the height of empire to explain the perceived insidious effects of tropical climates on the minds and bodies of British colonisers.

While the British were convinced they should be colonising the territories and peoples of India, the environment repulsed their efforts at every turn. The sun, the heat, the humidity – all were understood to cause a baffling variety of physical, mental and ‘moral’ diseases. The glorious imperial project relied on the image of white colonisers as superior to the colonised. But in reality, to be white in the empire meant to be physically vulnerable to the ravages of the hot climate.

Christie’s Theory of Insanity

Colonisers who suffered from mental breakdowns in India were sent ‘home’ for treatment in British asylums. While it was thought that their ‘native’ climate might assist the healing process, colonisers feared that the sight of mentally ‘weak’ white people could also undermine the carefully cultivated myth of European superiority in the eyes of colonised peoples.

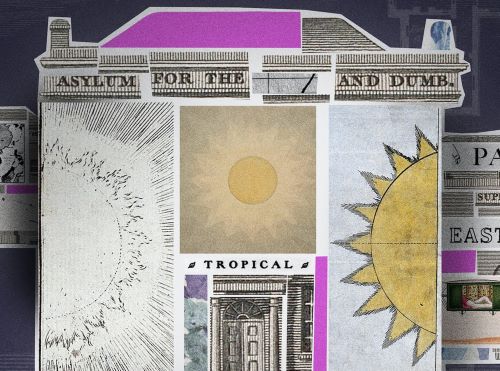

Established in 1870, the Royal India Asylum (RIA) was owned by the India Office and tasked with looking after ‘insane’ employees of the former East India Company. Patients received whatever treatment for mental health issues Victorian doctors could provide. Fresh air, chores, nourishing food and sedatives were the order of the day.

But these unique imperial patients served another purpose: research material for the asylum doctors. When dissecting their brains, Dr Thomas Christie was intrigued to find small pieces of bone. Were these “bony plates” the physical manifestation of exposure to the tropical sun? This theory was based on observations and post-mortems of white patients who had lived in India. Patients just like Edward Ripley.

Ripley was born in 1833 in Fort William, a bastion of British power in the Presidency of Bengal. At 16 he followed his father into the Indian Army, fighting in the so-called Indian Mutiny of 1857. In December 1872, he arrived in England for the first time, shipped there to recover at the RIA.

As with many fellow patients, his doctors assumed his erratic behaviour was the result of too much time under the tropical sun. Despite being a white European, he had actually never left India before. Suffering from the cold of his first London winter, he insisted on wearing gloves and a heavy coat even indoors.

After almost a year of treatment, Dr Christie released Ripley on a temporary ‘trial’ outside the asylum. In May 1873, he returned to ask for clearance to return to India. Christie informed him that once the tropical sun had infected his mind, there was no way to go back without risking another bout of insanity. Unable to return home, Ripley likely felt he was left with no other choice but to end his life.

The Costs of Being Part of the Imperial Machine

Ripley’s is one of many such stories in the archives of Britain’s asylums. The imperial project was built on the bodies of working-class white men who served the empire and were shipped back to Britain with no support or training, in poor physical and mental health, often with alcohol addiction. The glorious British Empire was glorious for very few.

Sunstroke insanity was just one way to explain a growing epidemic of mental disturbance in former imperial soldiers – an environmental diagnosis that conveniently turned attention away from the imperial military complex.

Surviving archives also tell us that sunstroke insanity was a distinctly white pathology. Britain’s Victorian asylums cared for many people of colour, some who were born or had lived under the tropical sun. ‘Sunstroke insanity’ was rarely, if ever, applied to them.

Take Frances Fiske, a Jamaican woman from near Kings Cross, admitted to Hanwell Asylum in 1886. Letters from her family show their conviction that the real cause of her condition was repeated sunstrokes as a child. Her doctors remained unconvinced. According to 19th-century medical opinion, black skin provided protection from the sun and many other ‘tropical’ illnesses.

Does sunstroke cause insanity? Heat stroke or heat exhaustion can cause severe neurological damage if left untreated. Is this why Ripley committed suicide? I’m not a medical doctor, but I don’t think so.

Ripley’s story is complicated and uncomfortable. He struggled with mental illness and was also undoubtedly involved in violent acts during his time in the army. I think Ripley’s life and death can tell us more about the high costs of the British Empire and the ways that Victorian notions of ‘whiteness’ were bound up in ideas about the environment, illness, and militarism. It’s clear that the lasting, damaging effects of imperialism on the bodies and minds of people in Britain are only just starting to be uncovered.

Originally published by Wellcome Library, 09.08.2022, under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.