By Claire Felter, Danielle Renwick, and Amelia Cheatham

Immigration has been a touchstone of the U.S. political debate for decades, as policymakers have weighed economic, security, and humanitarian concerns. Congress has been unable to reach an agreement on comprehensive immigration reform for years, effectively moving some major policy decisions into the executive and judicial branches of government and fueling debate in the halls of state and municipal governments.

President Donald J. Trump was elected on pledges to take extraordinary actions to curb immigration, including controversial plans to build out the border wall with Mexico, deport millions of undocumented immigrants, and temporarily ban Muslims. In office, he has scaled back his plans in some areas but pushed ahead with full force in others, often drawing legal challenges and public protest.

What is the immigrant population in the United States?

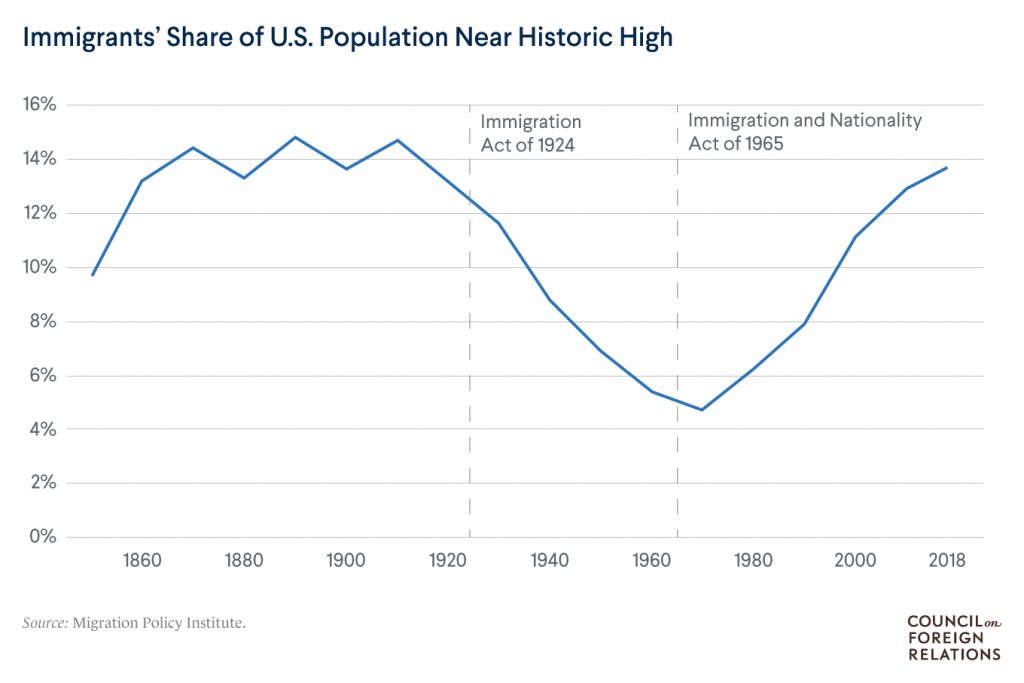

Immigrants comprise almost 14 percent of the U.S. population, or more than 44 million people out of a total of about 327 million, according to the Census Bureau. Together, immigrants and their U.S.-born children make up about 28 percent of U.S. inhabitants. The figure represents a steady rise from 1970, when there were fewer than ten million immigrants in the United States. But there are proportionally fewer immigrants today than in 1890, when foreign-born residents comprised 15 percent of the population. Mexico is the most common country of origin for U.S. immigrants, at 25 percent, but the proportion of immigrants from South and East Asia—who number about 27 percent—is on the rise.

Undocumented immigration. The undocumented population is about eleven million and has leveled off since the 2008 economic crisis, which led some to return to their home countries and discouraged others from coming to the United States. During the 2019 fiscal year, Customs and Border Protection (CBP) reported more than double the number of people apprehended or stopped at the southern border than in 2018. Still, southern border apprehensions remain well below [PDF] their levels in prior decades.

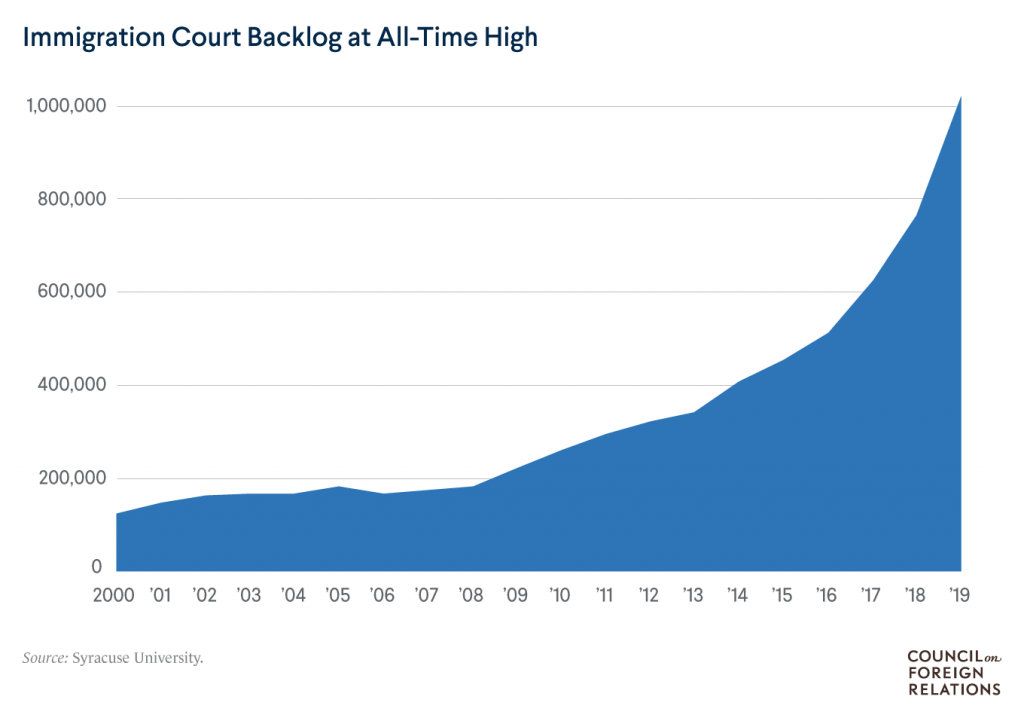

More than half of undocumented immigrants have lived in the United States for more than a decade; nearly one-third are the parents of U.S.-born children, according to the Pew Research Center. Central Americans seeking asylum, which is protected under U.S. law, make up a growing share of those who cross the U.S.-Mexico border. Some of these immigrants have different legal rights from Mexican nationals in the United States: under a 2008 anti–human trafficking law, unaccompanied minors from noncontiguous countries have a right to a hearing before being deported to their home countries. The spike in Central American migration has strained the U.S. immigration system, with more than one million cases pending in immigration courts.

Though many of the policies that aim to reduce unlawful immigration focus on enforcement at the border, individuals who arrive in the United States legally and overstay their visas comprise a significant portion of the undocumented population. A Center for Migration Studies report found that in 2010–2017 individuals who overstayed their visas far outnumbered those who arrived by crossing the border illegally.

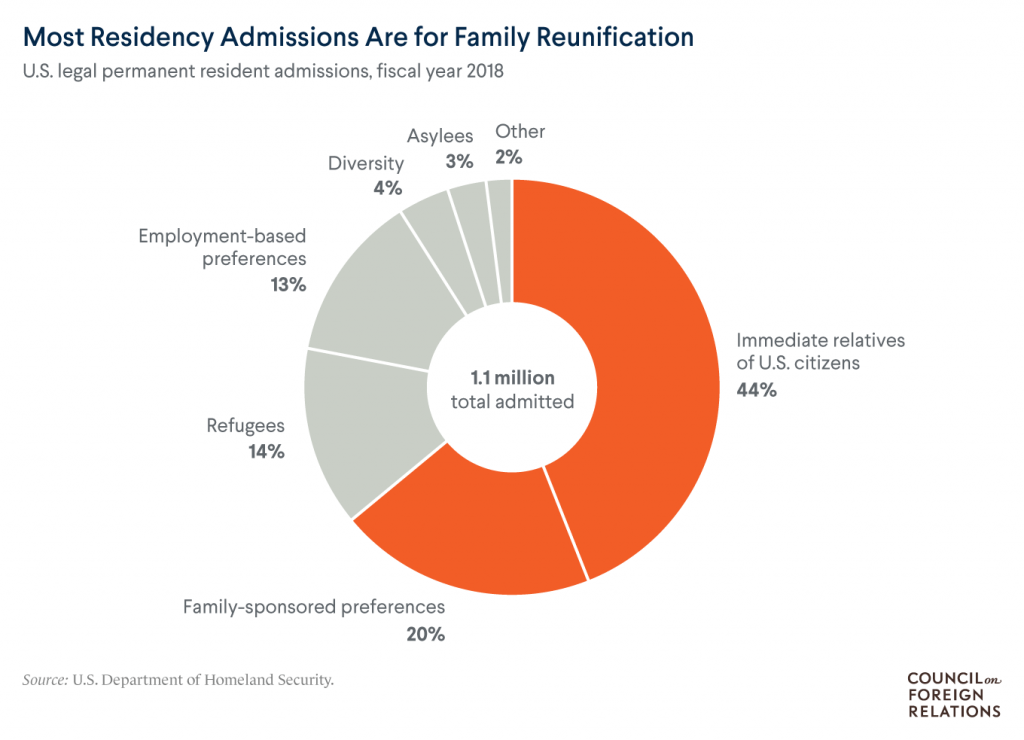

Legal immigration. The United States granted about 1.1 million individuals legal permanent residency in fiscal year 2018. Nearly two-thirds of them were admitted on the basis of family reunification. Other categories included: employment-based preferences (13 percent), refugees (14 percent), diversity (4 percent), and asylees (3 percent). In late 2019, about 3.5 million applicants were on the State Department’s waiting list for immigrant visas [PDF].

Hundreds of thousands of foreign nationals work legally in the United States under various types of nonimmigrant visas. In fiscal year 2019, the United States granted close to 190,000 visas [PDF] for high-skilled workers, known as H1B visas, and more than 300,000 visas for temporary workers in agriculture and other industries. H1B visas are capped at 85,000 per year, with exceptions made for certain fields.

Immigrants made up roughly 17 percent of the U.S. workforce in 2014, according to the Pew Research Center; of those, around two-thirds were in the country legally. Collectively, immigrants made up 45 percent of domestic employees; they also comprised large portions of the workforce in U.S. textile manufacturing (36 percent), agriculture (33 percent), and accommodation (32 percent). Another Pew study found that without immigrants, the U.S. workforce would decline from 173.2 million in 2015 to 165.6 million in 2035; the workforce is expected to grow to 183.2 million if immigration levels remain steady, according to the report.

How do Americans feel about immigration?

A 2019 Gallup poll found that 76 percent of Americans considered immigration a good thing for the United States. As many as 81 percent supported a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants if they meet certain requirements. A 2016 Gallup poll found that among Republicans, support for a path to citizenship (76 percent) was higher than support for a proposed border wall (62 percent).

What legislation has Congress considered in recent years?

Congress has debated numerous immigration reforms over the last two decades, some considered comprehensive, others piecemeal. Comprehensive immigration reform refers to omnibus legislation that attempts to address the following issues: demand for high- and low-skilled labor, the legal status of the millions of undocumented immigrants living in the country, border security, and interior enforcement.

The last time legislators came close to significant immigration reform was in 2013, when the Democrat-led Senate passed a comprehensive reform bill that would have provided a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants and tough border security provisions. The bill did not receive a vote in the Republican-controlled House of Representatives.

What actions did the Obama administration take?

President Barack Obama took several actions to provide temporary legal relief to many undocumented immigrants. In 2012, his administration began a program, known as Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA), that offered renewable, two-year deportation deferrals and work permits to undocumented immigrants who had arrived in the United States as children and had no criminal records. Obama characterized the move as a “stopgap measure” and urged Congress to pass the DREAM Act, legislation first introduced in 2001 that would have benefited many of the same people. As of September 2019, more than nine hundred thousand [PDF] had taken advantage of DACA. Obama attempted to extend similar benefits to undocumented parents of U.S. citizens and permanent residents in a program known as Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA), but the Supreme Court effectively killed the program in 2016.

The Obama administration’s enforcement practices drew criticism from the left and the right. Some immigrant advocacy groups criticized his administration for overseeing the deportation of more than three million people during his eight-year tenure, a figure that exceeded those of the administrations of Presidents Bill Clinton and George W. Bush. Many Republicans said the Obama administration, by narrowing its deportation efforts to undocumented immigrants who had committed serious crimes, was soft on enforcement.

What actions has the Trump administration taken?

PresidentTrump has signed several executive orders affecting immigration policy. The first, which focused on border security, instructed federal agencies to construct a physical wall “to obtain complete operational control” of the U.S. border with Mexico. Additionally, it called for an end to what it calls “catch and release” practices, in which certain unauthorized immigrants who were captured at the border would be allowed into the United States while they await court hearings.

The second executive order, which focused on interior enforcement, expanded the categories of unauthorized immigrants prioritized for deportation and ordered increases in enforcement personnel. It also moved to restrict federal funds from so-called sanctuary jurisdictions, which limit their cooperation with federal immigration officials.

The third order, which focused on terrorism prevention, banned nationals from Iran, Iraq, Libya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen from entering the United States for at least ninety days; blocked nationals from Syria indefinitely; and suspended the U.S. refugee program for 120 days.

These actions, particularly the ban on travelers from seven Muslim-majority countries, drew widespread protests and legal challenges from individuals, cities, and states. The Trump administration revised the travel ban twice, and it eventually found its way to the Supreme Court, where justices allowed [PDF] its third iteration to stand. In early 2020, the White House expanded the ban by suspending visa applications from Eritrea, Kyrgyzstan, Myanmar, and Nigeria and blocking permanent residency through the diversity lottery for citizens of Sudan and Tanzania. Officials framed the restrictions as national security measures, citing the countries’ failures to meet U.S. standards on information sharing and passport regulations.

Trump has slashed the annual cap of refugees admitted to the United States from 110,000 when he took office to 18,000, and he has sought to make it more difficult for individuals to seek asylum. More than 250,000 applied for asylum in 2017 [PDF]. That year, the Trump administration ended temporary protected status (TPS) for tens of thousands of Haitians, Nicaraguans, and Sudanese who were allowed to remain in the United States after environmental disasters and conflict in their home countries. Beneficiaries of TPS are permitted to live and work in the United States for up to eighteen months, a period that can be extended at the president’s discretion. In 2018, Trump ended the same relief program for hundreds of thousands of Hondurans, Nepalis, and Salvadorans. Beneficiaries of the terminated TPS programs can stay in the country pending litigation.

In September 2017, Trump announced plans to phase out DACA, which he called, along with DAPA, “illegal” actions by Obama, but challenges in the courts have so far prevented him from terminating the program. His administration’s attempts to add a citizenship question to the 2020 census were also blocked in the courts. Opponents said the move would have led to a significant undercount of immigrants and minorities.

The Trump administration has also ratcheted up previous administrations’ efforts to deter border crossings, including by those seeking asylum. In early 2018, it implemented what it called a zero-tolerance policy, in which authorities arrested and prosecuted everyone caught crossing the southern border without authorization. As parents faced criminal prosecution, they were held apart from their children. Presidents Bush and Obama had likewise faced criticism for widespread detentions.

In July 2019, the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) inspector general reported overcrowding and prolonged detentions [PDF] at CBP facilities, and investigators found that detainees, including children, were sometimes held without access to beds, showers, or clean clothes for weeks.

Since 2018, CBP has also implemented “metering,” or accepting a limited number [PDF] of asylum applicants each day and instructing others to remain in Mexico. Opponents charge that denying entry to asylum seekers violates U.S. law [PDF], as well as international standards. The administration expanded these practices in 2019 under its Migrant Protection Protocols, which require asylum seekers to stay in Mexico while their cases are pending. It also threatened to impose tariffs in order to pressure Mexico to beef up its border enforcement.

Trump has also sought to stem the influx of Central American migrants through “safe third country” agreements with El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras. The deals require asylum seekers transiting through these countries to apply for protection there first, and allow U.S. officials to deport migrants to the Northern Triangle without considering them for asylum. The agreements are facing court challenges.

Separately, Trump has acted to keep out immigrants who would require taxpayer-funded services such as Medicaid and SNAP food benefits. That move also faced court challenges, but in February 2020 the Supreme Court cleared the administration to implement the policy.

Where do the Democratic presidential candidates stand?

Candidates seeking the 2020 Democratic nomination are united in condemning the Trump administration’s changes to immigration policy, especially family separations, child detention, and new restrictions on refugees and asylum seekers. They generally support a comprehensive reform along the lines of the 2013 proposal. Many are also in favor of shielding Dreamers from deportation, raising the cap on refugees, and increasing aid to El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras—which Trump has withheld.

However, the Democratic field is split on border security and enforcement. They have different proposals on how to reform Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)—with some calling for the agency’s abolishment—as well as on how to prioritize deportations, how much to expand border barriers, and whether to decriminalize unauthorized border crossings, among other issues.

How are state and local authorities handling these issues?

States vary widely in how they treat unauthorized immigrants. Some states, such as California, allow undocumented immigrants to apply for drivers’ licenses, receive in-state tuition at universities, and obtain other benefits. At the other end of the spectrum, states such as Arizona have passed laws permitting police to question people they suspect of being unauthorized about their immigration status.

The federal government is generally responsible for enforcing immigration laws, but it delegates some immigration-control duties to state and local law enforcement. However, the degree to which local officials are obliged to cooperate with federal authorities is a subject of intense debate. More than seven hundred state and local jurisdictions limit their cooperation with federal authorities, according to the Immigrant Legal Resource Center.

President Trump decried these sanctuary jurisdictions throughout his campaign. After taking office, he issued an executive order to block federal funding to them and reinstate a controversial program known as Secure Communities, in which state and local police provide fingerprints of suspects to federal immigration authorities and hand over individuals presumed to be in the country illegally. He also ordered the expansion of enforcement partnerships among federal, state, and local agencies. Several cities and states have challenged the order [PDF] in court.

In 2018, the Justice Department filed a lawsuit against California, alleging that several of the state’s laws obstruct federal immigration enforcement. In February 2020, the administration announced new lawsuits against sanctuary policies in California, New Jersey, and Washington. Earlier that month, DHS barred New York residents from participating in programs to expedite their international travel after a state law made undocumented immigrants eligible for driver’s licenses and blocked federal immigration authorities from accessing motor vehicle records without a court order.

Some states have also protested Trump’s border security policies. After Trump called on states to deploy National Guards contingents to the southern border, at least five governors said they would refuse.

Originally published by the Council on Foreign Relations, 02.24.2020, under the terms a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International license.