By Dr. David Mislin

Assistant Professor, Intellectual Heritage Program

Temple University

Catholics, Unbelievers, and Elections

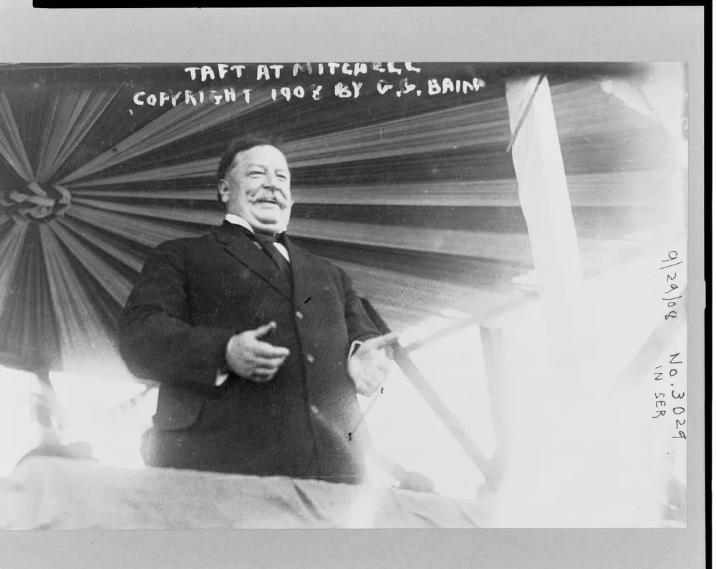

In the 1908 presidential campaign, the religious beliefs of the Republican Party nominee, William Howard Taft, came under attack. In response, another prominent Republican – the outgoing President Theodore Roosevelt – sounded the alarm about such attacks.

In that year’s election, Theodore Roosevelt declined to seek another term as president. Republicans nominated Secretary of War William Howard Taft to succeed him.

As the historian Edgar Albert Hornig chronicled, no sooner had Taft secured the nomination than “various elements of the Democratic campaign organization attempted to exploit the religious issue for political gain.”

Unlike in other instances – the politicization of John F. Kennedy’s Catholicism in 1960, for example – this was not a case of a candidate’s being criticized for one aspect of his faith. Taft was attacked on religious grounds, but for two very different reasons.

Some observers suggested that his wife and brother were both Roman Catholics and accused Taft himself of secretly practicing Catholicism. Given the anti-Catholic attitudes of the day, one voter privately expressed anxiety to Theodore Roosevelt that this “would be objectionable to a sufficient number of voters to defeat” Taft.

But there was another, more serious line of attack against Taft: He was a Unitarian. Taft refused to publicly discuss his own views. His opponents nevertheless emphasized that Unitarians typically rejected the divinity of Jesus and did not believe in such phenomena as miracles. Thus, these critics suggested, he was an unbeliever and would be actively hostile to Christianity as most Protestants understood it.

One voter insisted in a letter to Theodore Roosevelt that being a Unitarian was akin to being an “infidel.” Throughout U.S. history, being seen as an unbeliever has proved disqualifying for politicians.

Religion and Partisan Attacks

In pamphlets published during the 1908 campaign, W.A. Cuddy, a Protestant minister, insisted that “the religion of Jesus Christ” was “at stake in the coming election.”

In the same pamphlet, which was reported on in local and national publications, Cuddy further suggested that the United States “insults God by electing Taft.”

Taft’s specific beliefs mattered little. Perceived religious difference was enough to prompt partisan attacks. Roosevelt lamented this fact, noting, “it is claimed almost universally that religion should not enter into politics, yet there is no denying that it does.”

Pronounced as these attacks were, they did not cost Taft the election. With the help of religious Republicans who defended his faith convictions, Taft defeated William Jennings Bryan, his Democratic opponent, by a comfortable margin.

Roosevelt’s Prescient Warning

Late in 1908, after the election, President Roosevelt published a letter in newspapers nationwide responding to the attacks made on Taft. Though he had long defended religious freedom and diversity, Roosevelt justified not speaking out during the campaign.

As he noted, he considered it “an outrage even to agitate such a question as a man’s religious convictions for the purpose of influencing a political election.”

Yet Roosevelt had come to recognize the need to respond. In doing so, he offered two critical assessments.

First, he denounced discussions of a candidate’s religious views as an invasion of privacy. According to Roosevelt, Taft’s beliefs were “his own private concern … between him and his Maker.” Opening a candidate’s religion to public debate, he wrote, was a rejection of “the first principles of our government, which guarantee complete religious liberty and the right to each man to act in religious affairs as his own conscience dictates.”

Beyond this appeal to religious liberty, Roosevelt offered a dire warning about the effect of these attacks on civic life. He feared that “discrimination against the holder of one faith means retaliatory discrimination against men of other faiths.” Attacks on a candidate’s religion would only inspire more such attacks.

Roosevelt’s greatest fear was that this cycle of attack would poison civic life. Once attacks on a candidate’s beliefs became a normal part of campaigning, he warned, “there is absolutely no limit at which you can legitimately stop.”

In this election campaign, Joe Biden has been the victim of political attacks marked by vague questions of his own faith and suggestions that his policies would hurt Christians. While such rhetoric could be seen as meaningless, it could also have real consequences. As Theodore Roosevelt recognized over a century ago, it could poison the political discourse.

Originally published by The Conversation, 09.18.2020, under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution/No derivatives license.