No matter where people settled in Greece, they were rarely more than 50 miles from the sea.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Geology and Geography

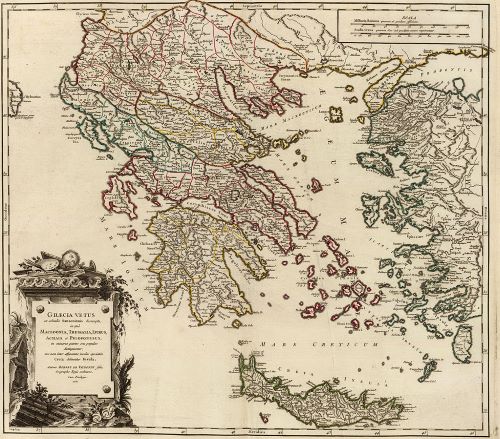

The Greeks called their land Hellas and themselves Hellenes. It was the Romans who called them Greeks- (Graeci ) and that is the name by which we know them.

The Greek historian Herodotus wrote that “Egypt is the gift of the Nile” but he never came up with an expression so memorable to describe his own country. Perhaps that was because the Greece he knew was never a united nation with fixed geographical borders. Rather it was a collection of city-states (although town-state or even village-state would have been more accurate for few had the population to be called a city.) These city-states were like a large family of quarrelsome brothers, almost always fighting with each other, but occasionally, banding together to battle against outsiders when they felt like doing so. Afterwards, they were as likely as not to turn on each other again.

In soft regions are born soft men.

Herodotus

The Greeks have often been described as “independent-minded” and there seems no doubt that geography played a major role in shaping that character. It was the mountains and the sea that molded Greece and Greeks into what they were.

Mountains in Greece don’t soar to the heights of other mountain ranges such as the Andes, Rockies, Alps or Himalayas-but they are extensive. In fact, about 80% of Greece is covered with mountains with the result that most settlements were less than 10 miles from a mountain. These mountain ranges isolated regions from each other more effectively than fences because what they lack in height they make up with steepness and ruggedness preventing or discouraging overland travel and communication.

No matter where people settled in Greece, they were rarely more than 50 miles from the sea. The philosopher Plato noted that the Greeks lived around the sea “like frogs around a pond.” A deeply indented coastline held between its rocky fingers a sea that could vary from tranquil to turbulent depending on the season and the weather. Most Greek mariners had experienced firsthand the sea’s treacherous currents and diabolical whirlpools.

During the summer months the sea tended to be peaceful. Being an inland body of water the Mediterranean Sea has almost no tides- less than a meter between high and low tides. It has little plankton (that’s why its waters are so clear), which means that it doesn’t support the extent and variety of sea life seen elsewhere but certainly enough to be both an important and welcome source of food.

Surrounded by water, the Greeks nevertheless faced a shortage of fresh water. Compared to many countries, there is a real scarcity of rivers and these often dry up to a trickle in the hot summer months. (Summer temperatures, because of the cloudless skies, are often hotter than in the Tropics.) The lack of rivers is offset somewhat by a plentiful supply of freshwater springs. These were precious and lifegiving and it is not surprising that they were considered to be sacred sites.

The Minoans

It is virtually impossible to talk about early Greek history without at some point introducing the Minoans. The Minoans were not Greeks nor do they appear to be closely related. What seems clear however is that they helped to shape the early Greek civilization, later immortalized by Homer and other Greek poets.

The Minoans have left a stunning visual legacy (paintings, sophisticated palaces and varied artwork) as well as large quantities of written records. Unfortunately, unlike the writings of the Egyptians, Hittites and Babylonians which shed light on such things as social organization, religious beliefs and historical events, those Minoan writings discovered so far are simply inventory records- detailed, plentiful but not as enlightening as one might hope. An added complication is that scholars have only been able to decipher a small portion of their written language.

What we do know is that the Minoans were gifted artists and that the subject matter of their artworks seems to have been heavily influenced by aesthetic considerations. Some have suggested that they may have loved art for its own sake, which would be an enormous change in the way art was traditionally created and used in other societies at that time. But more research on that possibility is needed.

Based on the evidence currently available, it seems that the Minoans arrived on the large island of Crete more than 5000 years ago. The soil was fertile, the climate was favorable and the numbers of people increased. Eventually a point was reached when the resources of the land were insufficient to meet the needs of the expanding population. Many migrated to nearby islands, those that stayed turned increasingly to trade as a means of improving their economic situation.

Successful and extensive trade resulted in a Minoan society that was wealthy and archaeology suggests that wealth was widely shared throughout the community. The extensive written records that do exist and have been deciphered show a highly controlled flow of goods into and out of state storehouses. The standard of living was high. Within the palace complexes… sophisticated plumbing, wonderful frescoes, plaster reliefs and open courtyards.

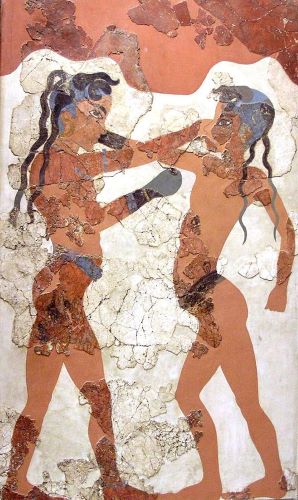

People had leisure time and devoted a good portion of it to sports, religion and the arts. While we can only guess at their religious beliefs, the remains of their artwork suggest a polytheistic framework featuring various goddesses, including a mother deity. The priesthood was also completely female, although the King may have had some religious functions as well. In fact the role of women- as religious leaders, entrepreneurs, traders, craftspeople and athletes far exceeded that of most other societies, including the Greeks.

Their system of government was that of a monarchy supported by a well-organized bureaucracy. According to myth, a King Minos, living in a palace with more than a thousand rooms, once ruled the island of Crete. In 1900 such a palace was discovered, excavated and partially restored by British archaeologist Arthur Evans. It was Evans who coined the term “Minoan civilization” in honor of the legendary King.

Around 1450 BC the Minoan civilization, which appears to have been peaceful and prosperous, came to an abrupt and probably violent end. There is evidence of wholesale destruction by fire and there has long been speculation that a volcanic explosion at Thera (followed possibly by a tsunami) ended this great civilization of the Aegean world. That hypothesis has now been called into question as recent studies of ice core samples push the Thera eruption further into the past.

The Mycenaeans

Around 2000 BC Greek-speaking immigrants moved into the Aegean. Skeletal remains confirm they were tall and well built. The newcomers looked first to the sea for food and later found that the dry and rocky soil was well suited for growing olives and grapes. It seems these people were a war-like lot, ruled by military leaders. In many ways they resembled the Vikings that would plague Europe some 25 centuries later- pirates, raiders and traders- who after a time settled down and became civilized. The term Mycenaean has been given to this civilization, derived from Mycenae, the site first excavated by Heinrich Schliemann after his discovery of fabled Troy.

The Mycenaeans began to trade and have cultural contact with the Minoans. The latter influenced the development of their cities, the production of trade goods and improvements in agriculture. Unlike Minoan cities, which had no or minimal fortifications, the Mycenaean settlements were heavily fortified with colossal perimeter walls. Since they periodically raided and looted towns in Hittite and Egyptian territory the massive fortifications were likely seen as a cost of “doing business”. The art themes depicted on Mycenaean artifacts (scenes of warfare and hunting) make a sharp contrast with the pastoral content of Minoan artwork. Their militaristic approach worked well for the Mycenaeans bringing power and prosperity. Between 1600 and 1200 BC their culture flourished.

Their religious beliefs seem to have been very similar to those of other ancient civilizations of the time and share in two important characteristics- polytheism and syncretism. Polytheism is a belief in many gods and syncretism reflects a willingness to add foreign gods into the belief system-even if the new additions don’t exactly fit. When the Mycenaeans first arrived in the Aegean they likely believed in a pantheon of gods headed by a supreme Sky God common to most Indo-European peoples. His name was Dyeus which in Greek became Zeus. Following contact with the Minoans and their earth goddesses, these goddesses were incorporated into the pantheon and that is likely the path followed by Hera, Artemis and Aphrodite.

It was the Mycenaeans that Homer immortalized in his two epic poems the Iliad and the Odyssey. The question that is often asked is “How much, if any, of those tales are true?” and the answer is that it is unlikely that that question can be completely answered in our lifetimes, if ever. Myth, history and archaeology – all different – but there are examples where they coincide remarkably, and others where they cannot be made to meet, despite the most earnest coaxing. Homer and his forefathers nursed the Mycenaean legends through the tunnel of the Dark Ages into the light of the later Greek world. How much was dropped off and added on in that journey is the subject of speculation and the stuff of debate. What is evident is that some of the content is clearly true and some is the product of imagination. Sorting one from the other has become a task for the ages.

So what happened to the Mycenaeans? The answer is that sometime around 1200 BC, when the Mycenaean civilization was at its peak, it suddenly appears to have collapsed. Some scholars feel we will never know with certainty what happened and why. There are lots of theories: their history of military violence finally caught up with them; natural disaster in an area plagued with earthquakes and volcanic eruptions; the possibility of drought and famine followed by civil uprising. There is evidence of a lot of migration.

Volcanic Eruption at Thera (Santorini)

In 1646 BC a massive volcanic eruption, perhaps one of the largest ever witnessed by mankind, took place at Thera (present day Santorini), an island in the Aegean not far from Crete. The explosion, estimated to be about the equivalent of 40 atomic bombs or approximately 100 times more powerful than the eruption at Pompeii, blew out the interior of the island and forever altered its topography. Possibly as many as 20,000 people were killed as a result of the volcanic explosion. Just as happened at Pompeii centuries later, a settlement on Thera known as the town of Akrotiri was buried under a thick blanket of ash and pumice.

For more than 3,500 years the ancient Bronze Age community lay hidden- one of Greece’s many secrets of the past. Then, as is often the case with various heritage sites, the town of Akrotiri was accidentally discovered. Quarry workers, digging out the pumice for use in the manufacture of cement for the Suez Canal, chanced upon some stone walls in the middle of their quarry. These eventually proved to be remains of the long-forgotten town. Archaeologists from France and later from Germany did some preliminary excavation in the second half of the 19th Century but it was not until 1967 that systematic excavation began at the site in earnest. Spyridon Marinatos, supported by the Archaeological Society of Athens, soon began to uncover the remains of the ancient town. It was not easy. Not only were the buried buildings two or even three stories tall, the original building materials (clay and wood) had been damaged by earthquakes, fire and the hands of time. It was necessary to proceed slowly and carefully. Work on the project has now been on-going for almost four decades and it is likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

The site has yielded some surprising information. Most startling of all is the fact that no human remains have been found at Akrotiri, unlike Pompeii and Herculaneum where the dead were buried in the midst of their daily activities. At Akrotiri, it was obvious that people had begun to do some repair work to their dwellings, probably in response to minor earthquake or volcanic damage. However, before the major eruption at least some of them had the time to pack up their families and most valuable possessions and leave. Huge pottery containers and large household furnishings were abandoned in their haste to depart but it seems clear that most people got away safely, were buried elsewhere or were swept away by the tsunami waves that might have accompanied such a massive eruption.

The Akrotiri site has not yielded huge amounts of gold, silver and bronze artifacts, nothing on the scale that might have been expected had the inhabitants been caught unawares. But a splendid visual legacy was left, most of it in pieces that are painstakingly being assembled by Christos Doumas and his colleagues. The frescoes at Akrotiri are spectacular, were exceptionally well-preserved by the protective blanket of ash that covered them and their locations can be correlated to various rooms within the town.

The paintings provide a lot of visual information that needs to be carefully analyzed- a fleet of ships manned by sailors allowing one to see how the vessels were rigged, how the crew was dressed, what they carried by way of tools and weapons; people in the community going about their daily activities, picking flowers, making religious offerings; two nude fishermen carrying strings of fish; young boys in a boxing match, etc.

Historians have been debating for years about exactly when the major eruption at Thera took place. Radio-carbon dating and dendrochronology (tree-ring dating) had narrowed the date down to a range of years but neither could confirm a specific year. Then improvements in the science of ice core dating made it possible to pinpoint a particular year-1646 BC- a century earlier than most historians had thought. (Ice cores drilled out of the Greenland ice cap show seasonal variation in the same manner as tree rings. The winter snow fall creates yearly bands and within that band the atmospheric activity is recorded. The volcanic eruption at Thera was confirmed as happening in 1646. At the present time, the core depth allows scholars to look back in time some 200,000 years and work will continue on making that timeline longer.)

The Golden Age of Greece

The “golden age” of Greece lasted for little more than a century but it laid the foundations of western civilization. The age began with the unlikely defeat of a vast Persian army by badly outnumbered Greeks and it ended with an inglorious and lengthy war between Athens and Sparta. This era is also referred to as the “Age of Pericles” after the Athenian statesman who directed the affairs of Athens when she was at the height of her glory.

During this period of time significant advances were made in a number of fields including government, art, philosophy, drama and literature. Some of the Greek names most familiar to us lived in this exciting and productive time. It was an era marked by such high and diverse levels of achievement that many classical scholars refer to the phenomenon as “the Greek miracle”. Even those who don’t believe in miracles will concede that it is possible that the ever-competitive Greeks were spurred on to higher levels of innovation in their field by seeing the bar being raised in so many other areas.

None of this would have happened without an encouraging environment and Athens was at that time at the “top of her game”. Her citizens were supremely confident, filled with energy and enthusiasm and utterly convinced that their city provided what a combined London – Paris – New York might offer today.

Military victory over the Persians, largely achieved under Athenian leadership, set the stage. The transition in government from the reluctant hands of the aristocratic elite into the mass of common people also played an important role. More people felt that their opinions mattered than ever before.

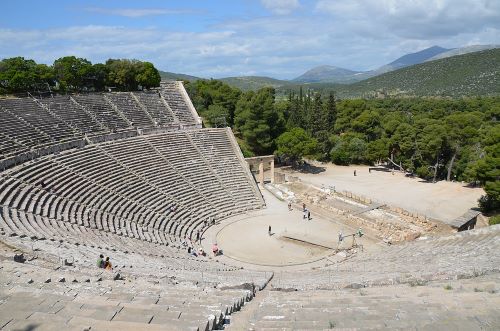

One of the greatest inventions of the ancient Greeks was drama. It evolved out of religious ritual and promptly proved to be both an enduring and popular creation. Greek tragedies, featuring historical and mythological events, were written and directed by authors such as Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. (Many feel that only Shakespeare merits inclusion in their company.) Each won numerous prizes and critical acclaim and each added innovations to the field of drama.

The lyric poet Pindar ushered in the era and became famous in his lifetime for victory odes written to celebrate athletic success. The writers of prose also flourished. Herodotus, regarded as the father of history, wrote several illuminating books on the Persian wars (and is still often consulted source on ancient Egypt). Another war historian, Thucydides, is still admired as a lucid and evocative writer. Plato, whose writings largely survive, is said to have penned the most poetical prose since the Bible.

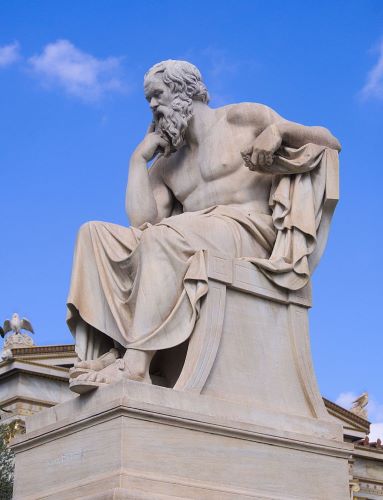

The golden age gave us Socrates who steered philosophy in the direction of morals, logic and ethics. His life, and the manner of his death, had a massive impact on other major figures of that epoch such as Plato, Aristophanes and Xenophon.

The physician Hippocrates, the sculptor Phideas, the architects of the Parthenon, all contributed to an era that truly deserves to be called “golden”.

What brought the golden age to an end? The long and mutually murderous war between Athens and Sparta, with their conflicting values and aspirations? Military misadventures? Dreams of imperialism? Possibly the best answer lies in what the Greeks call hubris. Perhaps Athens overstepped its bounds and failed to follow the twin admonitions of Delphi- know thyself and All things in moderation. Perhaps, like Icarus, it tried to fly too close to the sun.

The Alphabet and Writing

History

“Whenever Hellenes take anything from non-Hellenes, they eventually carry it to a higher perfection.”

Plato, Epinomis

According to the ancient Greeks they adapted their alphabet from the Phoenicians. Both were great seafaring peoples and eager to trade not only goods but ideas. One of the most important ideas was the alphabet. It enabled a system of writing by which they could record their transactions- 100 jars of olive oil, 20 blocks of white marble, 30 packages of purple dye, etc. As with other ideas they borrowed the Greeks made improvements, increasing the number of letters by adding vowels. This happened sometime around the beginning of the eighth century BC.

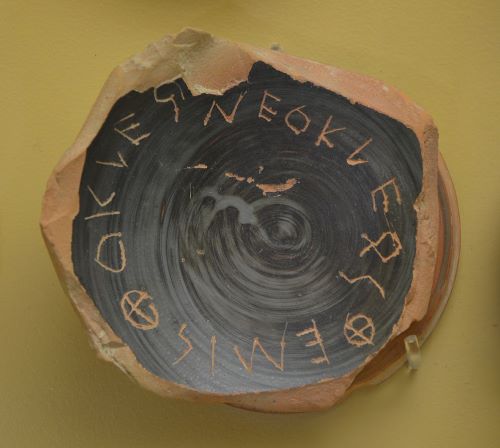

This was not the first time that Greek speaking peoples had used a written language. The Mycenaeans, who were the subjects of Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, had developed a system of writing that today’s scholars call “Linear B”. Several thousand sun-dried clay tablets covered with the Linear B script have been found on the island of Crete. They represent the earliest form of written Greek known. Deciphered by a young English architect (Michael Ventris), the tablets recorded details about the storage and distribution of household goods. The information was probably written around 1400 BC. Then, during the Dark Age, the knowledge of writing died out. The Greeks became an illiterate society.

With the adoption and modification of the Phoenician alphabet the Greeks were on their way to becoming literate again. In fact, the achievements for which they became renowned in fields as varied as philosophy, science, government, literature and medicine would not have happened if it weren’t for writing. Socrates wrote nothing but we know so much about what he thought and said because of the writings of Plato. Access to a simple writing system meant that everyone willing to learn could, in theory, do so –women, slaves, peasants as well as members of the aristocracy. In fact, however, most didn’t, and illiteracy was widespread during the golden age of Greece- the Classical Era.

The Mycenaean Greeks used sharp instruments to engrave their language into wet clay tablets. (A major fire at an ancient palace baked thousands of these tablets and preserved them for scholars today.)

Later Greeks used a variety of writing implements- papyrus (which they got from Phoenician traders), parchment (which was made from the scraped hides of cattle, ship or goats), wooden tablets whitened with gypsum, wooden tablets coated with wax and, of course, more durable materials such as stone monuments and bronze plaques. These more permanent materials were often used for official inscriptions- laws of the city, treaties with other states, temple dedications, war memorials and such.

Early Greek writing runs from right to left- for the first line. The second line then runs from left to right and the direction of the lines alternate for the complete text. This kind of writing is called boustrophedon (as the ox turns- when he plows a field.) Later the left to right system, which we use today, became the standard.

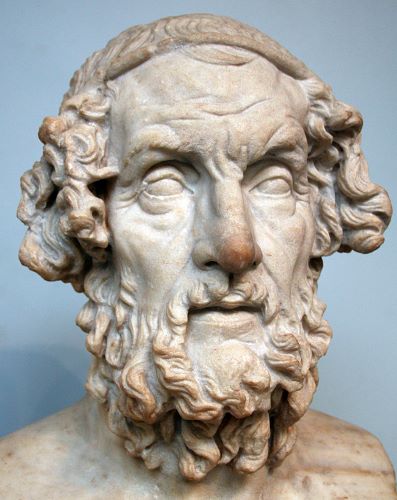

Homer

It was Homer (perhaps Homer of Chios) who wrote the two classic works of literature the Iliad and the Odyssey. (Actually, he likely didn’t “write”; it seems more probable that he “dictated” to a man legend identifies as Palamedes.) The way of life that is described in the two epic poems comes mostly from Homer’s own time although the period he describes extends backwards into Mycenaean times. There is still much uncertainty in academic circles about when the poems were written down-perhaps around 775BC – after centuries of being recited or sung. What is clear is that it would not have happened without the invention of the first true alphabet, the first writing that could be pronounced by someone who is not a speaker of that language.

So it is that the Gods do not give all men gifts of grace – neither good looks nor intelligence nor eloquence.

Homer

Although later generations of Greeks lauded Homer as the first and greatest Greek poet, they seemed to know little about the man himself. Various communities claimed that he was born or had lived there but the forensic evidence on the subject is not conclusive. Neither is the claim that he was blind although a well-known bust of the poet suggests that. Both the Iliad and the Odyssey reveal a wealth of information about Greek society and cultural expression during the Dark Age. The description of the bronze armor of Achilles, the evolution of the Greek polis (city-state) and the detailed accounts of battles are all vividly written and visually evocative. They have the ring of truth about them. Although it may not be possible to extract solid historical data from Homer he certainly taught the world how the ancient Greeks thought and felt about themselves.

The difficulty is not so great to die for a friend, as to find a friend worth dying for.

Homer

It is impossible to overemphasize his impact on Greek society. Homer gave his countrymen an expected model of behavior, a handbook of values. Students relied on Homeric texts, orators and politicians quoted him and philosophers and philologists dissected his poems. As more than one person expressed it, “I studied Homer so that I might become a better man.” Admirers included Alexander, the Great who slept with his sword and a copy of Homer by his bedside. The German archaeologist Schliemann would not have discovered (and inadvertently partially destroyed) the ancient city of Troy without the aid of Homer. His status as the greatest epic poet ever is rarely challenged.

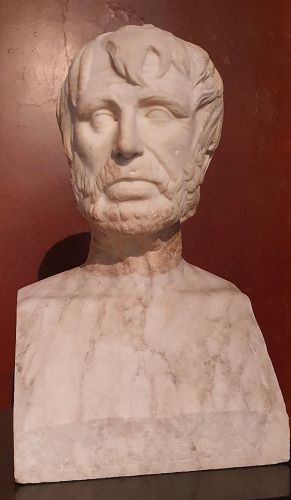

Hesiod

The poet Hesiod lived in the same timeframe as Homer, perhaps around 700 B.C. Most scholars agree that he was born in Boeotia and Hesiod himself in one of his major poems – Works and Days – characterizes his homeland as “a cursed place, cruel in winter, hard in summer, never pleasant”. (According to legend he became involved in a bitter land dispute with his brother which, if true, might have coloured his perspective on the matter.)

Hesiod’s birthplace was at the foot of Mount Helicon and tradition has it that the nine muses lived on the mountain. Hesiod credits them with inspiring his words, of breathing into him “a divine voice to celebrate things that shall be and things that were aforetime.” (Theogeny, lines 31-32)

Hesiod is remembered for two poems in particular- Works and Days and Theogeny. The former is an 800-verse poem that extols the virtue of honest labour, a sentiment echoed in later Christian writing that “by the sweat of thy brow thou shalt earn thy bread”. The latter work tells the story of the origins of the world and of the Greek pantheon. Hesiod is credited with a number of other poems but of these only fragments have survived. He is considered to be the first Greek didactic poet.

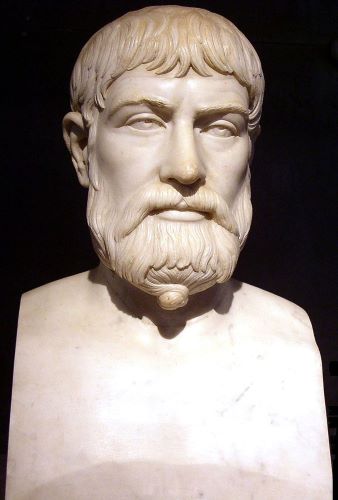

Pindar

Considered to be ancient Greece’s greatest lyric poet, Pindar was born in Thebes in 522 B.C. He produced a considerable body of work most of which has not survived but which are known in part from quotations by other authors. His victory odes (epinikia) which were composed to celebrate triumphs in various athletic festivals, have survived. These 45 victory odes linked athletic achievement, aristocratic ancestry and a rich mythology of gods and heroes.

Words have a longer life than deeds.

Pindar

Pindar came from an aristocratic family and his writings were greatly influenced by his upper-class upbringing. Since most of the clients for which he wrote victory odes came from a similar background, his poetry associates athletic achievement with elite status. His writings also had strong religious overtones stressing the victor’s linkage not only with noble origins but also with immortal entities. He clearly believed that “power is born in the blood”, that the nobility enjoys some form of kinship with the gods and that long after the victors are dead “poems and legends (will) convey their noble deeds”. In reading Pindar, the first reaction is to think that this poet belongs to the Age of Aristocracy. Instead, he flourished during the era of Pericles when many Greeks were being swept up in the groundswell towards democracy.

Sweet is war, to those who know it not.

Pindar

Pindar spent most of his life in Thebes. When Alexander, the Great razed Thebes for defying him, he instructed his soldiers to spare the family home of the long dead poet. That was probably partially in recognition of poetry that Pindar had written praising Alexander I of Macedon but also in recognition of the high esteem in which Pindar was held by all Greeks.

Religion

To the people of ancient Greece (as well as to earlier and neighboring civilizations) the universe they knew was filled with terrible forces not fully understood. Occasionally they saw dramatic demonstrations of power and might – violent thunderstorms, raging seas, gale force winds, eclipses, plagues, drought, earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, etc. It was not unreasonable to suspect that powerful and unpredictable entities were the cause of these events and that the originators might be appeased through prayer and sacrifice. In ancient times and in truly grave circumstances the ultimate gift of human sacrifice was made to placate those supernatural beings.

In time the number of these entities blossomed to represent or personify the virtues and vices of humankind, their wants, urges and fears. Eventually a complex realm was created, inhabited by greater and lesser gods and goddesses, heroes, titans, muses, graces, furies, fates, sirens and so on- each addition intended to account for another aspect of the human experience. Some of these deities and semi-deities were perceived as being benevolent; others were more likely to bring misery and distress. Petitions and sacrifices were made for two reasons: to make good things happen for the petitioner and to prevent bad things from coming to pass. The major deities lived on Mount Olympus and numbered twelve. Naturally, they were called “the Olympians”.

The king of the gods and father of many of them was Zeus. He was originally a weather god or sky-god controlling thunder, lightening and rain but as time went on he took on more responsibilities such as upholding justice and the law. Endowed with supreme strength and wisdom he was far more powerful than the other gods but, even so, he was subject to the limitations imposed by the three Fates, who controlled the destinies of humankind and, some said, of the gods themselves.

The god Poseidon, a brother of Zeus, not only looked after the seas; he was also in charge of earthquakes and horses. Quarrelsome, surly, petulant and greedy were some of the adjectives used to describe him and he was reputed to hold a grudge for a long time. His symbol was the trident or fish spear which could cause earthquakes or create springs when struck on the ground.

Hera was the sister and wife of Zeus, which automatically made her Queen of the gods. She was also considered to be the goddess of marriage, a particularly daunting task given the roving eye of the King of the gods- little wonder she was accused of being jealous.

Athena was the Greek goddess of wisdom and the daughter of Zeus and the goddess Metis, believed to be the wisest deity. Athena also looked after arts and crafts (technology) and was regarded as the guardian of the working woman.

Aphrodite was the goddess of love and concerned with beauty and procreation. She held a special place in the hearts of sailors.

Apollo was the god of music, of health, healing and human enlightenment. His twin sister Artemis was the goddess of hunting and, oddly enough, guardian of wildlife.

Ares was the god of war and essentially a troublemaker. Other major deities include Demeter, goddess of agriculture, Hermes, messenger of the gods as well as Dionysus and Hephaistos.

The ancient Greeks had no word for “religion” which they viewed as being part of everything they did. Nor did they believe in the separation of “church” and state. It was felt that the safety and security of the state was dependent on a good relationship with the gods. Anyone who offended the gods could be found guilty of impiety and sentenced to death, as happened to Socrates. No one undertook anything of an important nature- such as a voyage, a battle or a construction project without first seeking the blessings or support of a particular god. And when the task was successfully completed, thanks were given in the form of offerings or, perhaps, by the dedication of a plaque or monument. It was this practice that gave birth to most public buildings and monuments including the altar of Zeus at Pergamun and the renowned Parthenon.

The Greeks believed that the gods could see everything that humans did and could, if they choose, fulfill such needs as food, shelter and clothing as well as wants like love, wealth and victory. They sought the protection of the gods from their enemies, disease and the forces of nature. Ancient inscriptions and surviving writings show that the prayer usually sounded something like this…

Oh Great Poseidon, brother of Zeus, Lord and Ruler of the Seas, I call on you to help me once again. Last year I asked you to protect my ship and its crew during that violent storm. You made the waters tranquil almost immediately and I honored your name with offerings in your temple. This time, on the day of the month sacred to you, I am beginning a long voyage to a distant land and I seek your blessings for fair weather and calm seas. At dawn today I ask you to accept this offering.

Note that the prayer begins by identifying the god/goddess being petitioned, and the realm for which he or she was responsible. Former requests are mentioned, the results and the offerings made. Then the new request is presented for consideration.

According to an ancient Greek myth it was the titan Prometheus who was instrumental in determining the nature of the offerings to be made to the gods. He made up two bundles from the body of a sacrificed animal. In the smaller bundle he put all the choice cuts of meat. In the larger, he put the bones of the animal and covered it with fat. Zeus was asked to select the portion that should always be offered to the gods. Zeus quickly, and rashly, selected the larger bundle finding out later that he had passed up on the better portion.

If you find Greek religion and mythology to be a bit confusing and contradictory and feel that the behavior of some of the gods and goddesses was sometimes outrageous and improbable, then you are not alone. You are in the company of many Greeks who began some one hundred generations ago to question as to whether or not there might be better (although less interesting) explanations about the origins of the universe and themselves. They took their first steps into the discipline of philosophy.

Science and Philosophy

The safest general characterization of the whole Western philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.

Alfred North Whitehead

The ancient Greeks didn’t make a distinction between philosophy and science, nor did they recognize the range of disciplines such as physics, chemistry, mathematics, astronomy, etc. that we do today. There simply wasn’t the depth of knowledge and range of information that later made separate disciplines practical. In the Greek era, one individual could be an expert in several fields. Nowadays, with the tendency of specialists to know more and more about less and less (i.e. intensive knowledge about a rather limited field) the ability to keep abreast of detailed research in more than one area becomes almost impossible. But in the days of Thales, Pythagoras and Aristotle that was the norm. People expected an individual knowledgeable in one area to also be proficient in others. And many were.

We are what we repeatedly do.

Aristotle

The Greeks had great success in the areas of mathematics, particularly geometry, borrowing heavily from the Egyptians (who were concerned primarily with practical applications) while raising the theoretical and intellectual bar to new heights. Euclid’s classic book on the Elements of Geometry was the world’s main textbook for almost two millennia.

They also made their mark in astronomy. An understanding of astronomy was important in understanding and regulating the business of agriculture. It was also essential in developing an accurate calendar and critical for navigation. While the Egyptians and Babylonians had made great advances in astronomy, their work was based heavily on centuries of observation. It was the Greeks who introduced mathematics into astronomy greatly expanding the range of questions that could be asked and answered about the solar system. In the 3rd Century BC, the Greek astronomer Aristarchus advanced the theory that the sun, not the earth, was the center of the solar system. It took the world the better part of two millennia to come to the same conclusion. Eratosthenes, another Greek, accurately calculated the earth’s circumference and its diameter.

Physics, the study of the nature of things, began seriously in Greece in the 6th Century BC. With few exceptions (e.g. the work of Aristotle and Pythagoras) the study was an intellectual pursuit unaided by much in the way of controlled experimentation, which is standard practice today.

It was Aristotle, equally at ease as a philosopher and as a scientist, whose several treatises on animals laid the foundations of zoology. Aristotle also did important work on plants, although not nearly to the same extent as his thorough publications on animal life, but he did have a strong influence on other scholars, such as Theophrastus, who laid the groundwork for the science of botany.

One swallow does not make a summer.

Aristotle

Socrates, although we have no evidence he ever wrote anything, was the first of the great thinkers of Athens. We can get some understanding of his ideas from the writings of Plato and Xenophon. Socrates challenged the morals and quest for power of his fellow citizens and paid the ultimate price of his life. He is remembered as the father of the study of ethics.

There were several factors that influenced the development of medicine in ancient Greece. First, there was the potent force of religion with its gods and goddesses who dealt with healing, death and pestilence. Then there was the influence of trading contacts such as Egypt (which had learned much from its mummification practices) and Mesopotamia (which had published comprehensive medical documents on clay tablets well before 1000 BC). From these and other Eastern areas, the Greeks also developed an encyclopedic range of herbal medicines.

To cap it off, there was the sad result of war – a variety of wounds and amputations caused by arrows, swords, spears and accidents- and described so vividly and accurately in Homer’s Iliad. Just dealing with these casualties provided lots of experience and practical information applicable elsewhere. Although Greek religion frowned on human dissection in the Archaic and Classical periods, after the founding of the Alexandrian School that changed. Physicians and researchers made advances in some areas that were not surpassed until the 18th Century.

The transition from believing that illnesses originated with the gods and the realm of evil spirits (a belief perhaps universally shared with all early civilizations) to the realization that there were natural causes involved did not happen easily or suddenly. For many generations two belief systems, one rooted in religion and one based on an emerging science, co-existed. Hippocrates, the Greek Father of Medicine, wrote “prayer indeed is good, but while calling on the gods a man should himself lend a hand.” To that end there were healing centers established where the faithful might pray while receiving the benefits of medical treatment. Hippocrates and his followers took a giant step forward in the science of medicine when they asked themselves the question “How did this illness come to be?” instead of “What god or force of evil caused this illness?”

Man is by nature a political animal.

Aristotle

Just as war drove significant improvements in medical practices so, too, did it have an impact on the field of engineering. Scholars such as Archimedes became military engineers, inventing and improving defensive and offensive weapons. There were, in addition, other innovations such as the gear, the screw, the steam engine, the screw press and so on but the prevailing Greek attitude towards manual labor and labor-saving devices did not greatly encourage nor reward innovation (except in the military sphere) so many inventions remained curiosities rather than instruments of change.

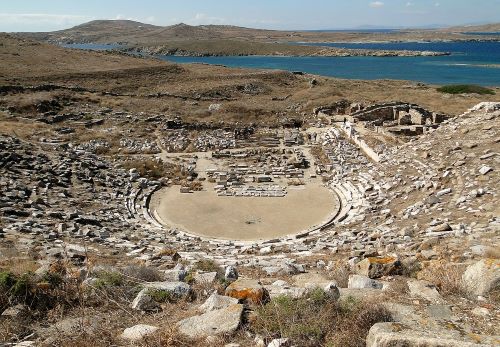

The Olympic Games

The ancient Olympics first took place in 776 BC at a place called Olympia, a sacred site dedicated to Zeus, king of the gods. (Located in the Alpheus river valley in southern Greece, Olympia should not be confused with Mount Olympus, located in northern Greece and legendary home of the major Greek gods.) Olympia was not only the original site of the Olympics; it was the permanent venue for 293 successive Olympics- one every four years for almost 1200 years. Among the ancient Greeks, a pilgrimage to Olympia to see the athletic events and to participate in the sacrifices to Zeus and other festivities was something of great importance and many people attended several times. Because it was a pagan festival it conflicted with the growth and spread of Christianity and Roman emperors, who were Christian, banned the Olympics around 400 AD.

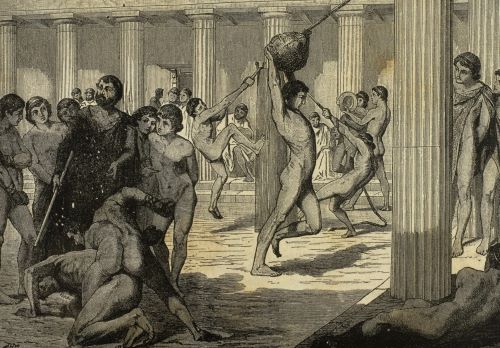

For the first dozen or so Olympic games there was only one athletic event and that was the stadion or 200 meter (210 yard) race. The distance corresponded to the length of the stadium track. Later, other events were added. In the beginning the athletic contest lasted only one day but that was later increased with the addition of other competitions. The athletes, all male, competed naked. Since there were no stopwatches, there are no records of the winning times but the names of the winners and the various events they won over the years were carefully documented. Records show that in 724 BC a 400 meter (420 yd.) race was added and then, in succeeding years, other events (wrestling, boxing, chariot races, pentathlon, and longer distance races) were also included, increasing the success and popularity of the games.

Those headed off to the Olympics were making a religious pilgrimage and anyone who interfered with their passage was deemed to have committed a sacrilege against Zeus himself- something no Greek would do lightly. Wars were suspended, personal feuds were put on hold, and bandits and mercenaries took a holiday so that the travelers could make their way to and from the Olympic site without fear for their safety. Depending on the distance and the weather, it could be a daunting trip. Despite the difficulties a remarkable number of Greeks, including Socrates, made the trip and made it more than once.

Socrates offered the following advice to a timid prospective spectator:

What are you afraid of? Don’t you walk around all day in Athens? Don’t you walk home to have lunch? And again for dinner? And again to sleep? Don’t you see that if you string together all the walking that you do in five or six days anyway you can easily cover the distance from Athens to Olympia?

For the athletes it wasn’t just a matter of showing up on the day of the competition and performing. 30 days before the games began; athletes had to register in person before the ten Olympic judges. Many would be accompanied by their personal trainers and coaches. The first thing that the judges did was to ensure that the athlete presenting himself was truly Greek and eligible to compete. The second thing was to make certain that those who wanted to compete were capable of doing so at the highest level. To that end, the judges conducted trials and workouts calculated to weed out those at the weaker end of the spectrum. The competitors ate together at a common mess to ensure that no one gained an advantage with secret recipes and magic potions. It is interesting to note that there were no team sports at those Olympics.

Women in Ancient Greece

The male is by nature superior and the female inferior…the one rules and the other is ruled.

Aristotle

In comparison with other civilizations in the ancient world, Greek women in general did not enjoy high status, rank and privilege. Even so enlightened a man as Pericles suggested in a major public speech that the more inconspicuous women were, the better it was for everyone. Sparta, which history clearly ranks as the cultural inferior of Athens on almost every scale, seems to have had a superior record in its treatment of women. And it wasn’t outstanding.

At social gatherings, intellectuals argued that perhaps men and women were two separate species. Men had more in common with the gods, while women had far more in common with the animal kingdom. (Perhaps this was an earlier, and fundamentally flawed, version of Men are from Mars: Women are from Venus). In any event, despite the efforts of many to ensure that women stayed in their proper place in the home and out of sight, a few did succeed in escaping that orbit. None flew as high as women in Egyptian society where several attained the highest office in the land- that of Pharaoh- but some Greek women managed to leave a public legacy. Following are three of them.

Penelope, wife of Odysseus, may not have existed at all but she still succeeded in leaving a legacy taught to new generations of Greeks for centuries by itinerant poet-storytellers. The virtues, values and roles ascribed to Penelope became, in effect, the standard to which women in that situation were expected to aspire. The story is well known.

Odysseus, King of Ithaca and the man responsible for the idea of the Trojan horse tried to return home after the long war with Troy. But he had offended Poseidon and the ruler of the seas threw many obstacles in his path. Odysseus, a reluctant warrior, had left his household in charge of his wife. Now she was being besieged by suitors who thought her husband was dead and wanted his wife and valuable property. Penelope outsmarted them. The woman that Homer portrays is one who can stand on her own two feet, is a partner with her husband in the life of the family and a real role model.

Aspasia, daughter of Axiochus, was born in the city of Miletus in Asia Minor (present day Turkey) around 470 BC. She was highly educated and attractive. Athens, at that time, was in its golden age and as a city must have had the kind of appeal that New York, London and Paris have today. Aspasia moved there around 445 BC and was soon part of the local social circuit. Some of the most influential minds of the era spoke highly of her intelligence and debating skills. Socrates credited her with making Pericles a great orator and with improving the philosopher’s own skills in rhetoric. She contributed to the public life of Athens and to the enlightened attitude of its most influential citizens.

Hypatia, daughter of Theon of Alexandria, was born in that city around 350 AD. She studied and later taught at the great school in Alexandria. Some modern mathematicians acclaim her as having been “the world’s greatest mathematician and the world’s leading astronomer”, a viewpoint shared by ancient scholars and writers. She became head of the Platonist school at Alexandria lecturing on mathematics, astronomy and philosophy attracting students from all over the ancient world. Political and religious leaders in Alexandria sought her advice.

Democracy

Ancient Greece, in particular Athens, is rightfully credited as the birthplace of democracy. Democracy is “rule by the people” and rule by the majority is implied. Up to this time, in most societies, rule was by kings, pharaohs, emperors, chiefs, warlords- powerful men (usually) who had become accepted as leaders because of their superior skills or force of personality.

Usually, their position then became a hereditary one, passed down to the eldest (or strongest) son. Kinship played an important role with powerful families and clans supporting the right of the king to rule. In some societies, the king was also the High Priest and had the additional power of religion to back his claim. The idea that common people had the ability to govern was a new and radical one.

The road began with Draco. In the early 7th century BC Athens, and the surrounding area of Attica, was a community governed not by laws but by tradition. If a family member was killed (deliberately or accidentally) it was up to the family to seek retribution. That could take the form of killing a member of the offending family or obtaining a suitable financial penalty from them. (In fact there were established sanctuaries in which families in danger could take refuge while the financial details of a settlement were being negotiated.)

The poor and the weak were at a disadvantage in this system against powerful households. Eventually this caused considerable unrest. So, by some unknown process, an individual named Draco was chosen as a lawgiver, to put crimes and punishment into a body of laws that everyone had to obey. This he did during the 39th Olympiad (between 624-621 BC). For the first time the Greeks had the rule of law to guide them rather than individual discretion or preference. This had the effect of making the state and not the family responsible for enforcing the law and the intention was that the law would apply equally to all men, rich or poor.

For the first time a distinction was made between someone killed deliberately and someone killed accidentally. Previously there had been no distinction made and the penalty was the same. (Even things could be punished. There is a story told about a statue falling on top of someone and killing him. The statue was flogged and cast into the sea as punishment.)

Draco’s laws may have been fair but they were severe. Death was the punishment for offences that we might consider minor. Generations later a Greek orator lamented that Draco’s laws were written not in ink but in blood. The laws also did not address a major problem at the time- people were being put into prison or forced into slavery because of debt. Soon it became evident that the laws needed to be reviewed and revised.

The man chosen by the people for this task had a reputation for wisdom. Solon was both a politician and poet. Since most of his writing has survived it is possible to get an insight into his philosophy and thinking. His task was challenging- to address social inequities that by this time had Athens hovering on the brink of civil war – and to do so without alienating either the rich or those crushed by debt.

What was urgently needed and what Solon provided was economic reform. He forgave debts secured by either land or personal liberty and he forbade entering into such contracts in the future. He sidestepped the issue of land re-distribution while offering poor farmers the prospect of a brighter future. The laws of Draco were repealed and replaced with a more humane code of conduct that covered civil, criminal and religious matters. This became the foundation of the Athenian legal system for at least the next three centuries. New standards were set in place for weights and measures, coinage and other economic instruments. Wealth, not birth, determined eligibility for political office with those contributing most to the economy having a greater voice in managing it. Then, after securing a promise from the citizens not to tinker with the new system for a decade, Solon left Greece to travel abroad.

Although Solon’s legal legacy remained in use for some fifteen generations his political system did not last beyond his lifetime. An economic tug of war broke out among the various factions over the issue he did not address- the redistribution of land. Finally, a wily nobleman named Peisistratus seized power and formed a dictatorship to rule over Athens. In addition to land reform, he also made other economic improvements, carried out an extensive public works building program and was a strong supporter of the arts. Although called a “tyrant”, a better description would be a benevolent dictator, who earned a reputation during his reign as a principled, fair and humane ruler.

His son Hippias did not do as good a job and was forced from office. A Greek aristocrat named Cleisthenes, who deserves recognition as the father of Athenian democracy, fought for the concept of greater citizen involvement in the political life of Athens. He recognized that the traditional tribal organization of the city had become a divisive rather than a unifying force. A new re-organization split up the tribes and balanced representation. From then on, individuals were not only encouraged to participate in what became known as Athenian democracy; they were required to participate.

The next great leader of Athens was Pericles who believed strongly that society functions best when all citizens are free and share in the running of the state. So, in the space of 150 years the center of power had moved from those of aristocratic birth, to those with wealth, to the common people. Although the style of government under Pericles was called a democracy the great Greek historian Thucydides said, “It was in theory, a democracy, but in fact it became the rule of the first Athenian.” (Pericles) The viewpoint of Pericles was expressed best in a funeral oration he gave in 430 BC, of which an excerpt follows:

Our system of government does not copy the systems of our neighbors: we are a model to them, not them to us. Our constitution is called a democracy, because power rests not in the hands of the few but of the many. Our laws guarantee equal justice for all…as for the election of public officials, we welcome talent to every arena of achievement nor do we make our choices on the grounds of class but on the grounds of excellence alone…we differ from other states in regarding the man who keeps aloof from public life not as “private” but as useless…great indeed are the signs and symbols of our powers…men of the future will wonder at us, as all men do today…

Athenian democracy was quite different from what we would consider to be democratic today. At that time, not everyone was considered a citizen and eligible to vote. Women were not citizens and so could not participate in any fashion. Neither could Greeks from other city-states living in Athens, nor foreigners, nor the large slave population. In a city of perhaps 300,000 less than 40,000 males were citizens and participants in the new democracy. But it was a giant step forward as far as government of, by and for the people was concerned.

One might ask, “Why did democracy develop first in Athens?” Answers vary. Some have suggested that the inhospitable soil (which Plato compared to a bony skeleton) played a part. A Greek myth speaks of Zeus apportioning the land of the World. First he ran all the soil through a sieve and distributed it to the various nations. Left in the sieve were rocks, pebbles and parched earth. This he tossed over his shoulder saying “That’s for Greece”. In those conditions people had to fight the soil and it toughened their spirit.

Others credit the sea as the source of independence, still others the isolation of communities and the need to make one’s voice heard whatever the eventual outcome. As Pericles noted “Instead of looking on discussion as a stumbling block in the way of action, we think it an essential preliminary to any wise action at all. “

It was likely a unique combination of circumstances and individuals that converged to create a system of government built around the contributions of the common man.

Science of Archaeology

The Dictionary definition of “archaeology” reads like this- The scientific study of material remains (as fossil relics, artifacts and monuments) of past human life and activities.” (Webster’s) Paul Bahn has a more memorable one…

Archaeology is rather like a vast, fiendish Jigsaw puzzle invented by the devil as an instrument of tantalizing torment, as Paul Bahn writes:

- It will never be finished

- You don’t know how many pieces are missing

- Most of them are lost forever,

- You can’t cheat by looking at the picture.

One image we may have of archaeologists comes out of Hollywood- the “Indiana Jones” model- a tall, lean man wearing a battered leather hat, revolver mounted on his hip, a half-smile on his tanned face as he contemplates a dangerous quest to a foreign land in search of some kind of treasure, pursued by bad guys, adventure lurking around the next exotic corner. That picture was not entirely fabricated. It was based on the exploits of early explorers- people such as the American dinosaur hunter Roy Chapman Andrews and Britain’s Sir Austen Henry Layard, both of whom made astonishing discoveries amidst the dangers and challenges of disease, poisonous snakes, natural disasters, ruthless bandits, civil war and corrupt bureaucracies. Both have been suggested as the inspiration for the Indiana Jones character.

One should not conclude that archaeology is something that began in the past 2-3 centuries. More than two millennia ago the king of Babylonia ordered the careful excavation of a temple in the city of Sippar (located southwest of today’s Baghdad) to see if he could determine who had built the temple. Ancient Greeks of the same era did some archaeological excavations in Delos, trying to make sense of the grave goods they found buried with the inhabitants. However it is in the last 2-3 centuries that archaeology has evolved into a science, one whose goal of treasure hunting has been replaced with the goal of uncovering the secrets of the past. That sentiment is best expressed in the observation of General Augustus Pitt-Rivers that, in general, everyday objects are more useful in interpreting the past than unique ones are.

Along the way though, archaeology has had its colorful characters, some of whom were extremely gifted individuals blessed with imagination and curiosity (and, sometimes with money), some had well-developed linguistic talents, others had organizational and leadership skills coupled with a lot of self-confidence. Most had a passionate desire to solve puzzles that had stumped their predecessors- lost cities, forgotten languages, buried temples, things remembered only in myths and legends. These were the kind of challenges that drove people such as: Jean-Francois Champollion, Heinrich Schliemann, Michael Ventris, Yuri Knosorov, John Lloyd Stephens, Sir Arthur Evans, General Augustus Pitt-Rivers, Sir Mortimer Wheeler, Howard Carter, Sir William F. Petrie and a host of others.

Often it was well-diggers, farmers, construction workers, hikers, cavers or children playing who stumbled upon something that later proved to be an important piece of local heritage. In such a manner were the tomb of the First Emperor of China, the Lascaux Caves, the buried Bronze Age city of Akrotiri and many other archaeological sites brought again to the attention of the public. Natural processes such as erosion, flood and earthquakes exposed other long-hidden secrets to the light of day. Once discovered, quick action was required in order to prevent destruction of the site by modern day tomb robbers, tourists and souvenir hunters. There have been many instances where the authorities didn’t act quickly enough.

In the early days, excavation and archaeology were considered to be almost synonymous terms. Excavation is still the main method of investigating most sites. Excavation tools range all the way from bulldozers down to shovels, picks, dental tools and paint brushes. The most important tool, generally, and the one that is practically a symbol of the archaeology profession is the mason’s trowel- a sharp-pointed, wedge-shaped implement that looks somewhat like a pie lifter with a wooden handle. In the hands of an experienced archaeologist the trowel can remove a lot of earth, delicately, in a short period of time without damaging the artifacts.

Today a wide range of tools, virtually all developed for other applications, can be used in an archaeological examination. Some are more suitable than others, depending on the characteristics of the site and the preferences of the archaeologist. As in any profession, some practitioners are more comfortable and proficient with certain tools than others. Some have taught themselves to handle a bulldozer as delicately as a surgeon’s scalpel. Some place their reliance on tools and techniques that others use sparingly or not at all. It could be said that there is a lot of art as well as science in the realm of archaeology.

The term “stratigraphy” in archaeology refers to occupation layers. Digging down through each layer or stratum the experienced eye will notice differences in the colour of the soil, differences in the type of soil and differences in the materials that are found in the soil. It is like cutting through a layer cake with the layers on top, of course, being newer or more recently laid down than the layers on the bottom. (You do have to be careful that the layers weren’t disturbed, turned over by a shovel, plow or animal or pulled out of position by a well or pit, so that the layers are reversed or mixed up.) Stratigraphic analysis is a very important tool in archaeology, as it is in geology. In the film one can clearly see the different strata or layers laid down by the erupting volcano.

Ice core dating is very similar to dendrochronology or tree ring dating. Seasonal variation in both the ice cores and tree rings allow one to count the number of years shown in an ice core or wood sample. One of the inclusions regularly found in ice core samples is volcanic ash. In the film the presence of such ash was used to establish a precise date for the volcanic eruption that destroyed Thera.

In the film Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) is shown in action. The equipment can also be put on a small cart or wagon and pushed or pulled around the site. GPR works by sending ultra high radio frequency waves down into the ground. These reflect off buried walls, pipes, etc. and provide an electronic profile of what may lie beneath.

Different trees and plants produce different amounts and types of pollen (microspores involved in plant reproduction). These vary throughout time and place. By collecting and analyzing the spores it is possible not only to build up a picture of a particular environment; that environment can also be dated. Pollen analysis is an important tool in understanding the environmental challenges faced by prehistoric peoples.

Computer technology has revolutionized the practice of archaeology just as it has had an enormous impact on most other professions. A generation ago it could take years to collect, sort, analyze and publish the data from an archaeological excavation- particularly if the site was at all complex. Now laptops right on the site can collect the information and there are software programs that can shorten the sorting and analytical timeframe considerably. Instead of moving heavy columns, “what if” programs can be used to try out different configurations and models on the computer. In the film, Professor Doumas confirms that the computer has become an indispensable archaeological tool.

In recent years some archaeologists have become interested in what is called experimental reconstruction. Using stone tools produced by the same techniques used by prehistoric hunters the archaeologists have butchered both elephants and bison to find out how the process was done, how long it would have taken and how tools marks found on ancient mammoths compare. The voyage of the Kon-tiki by Thor Heyerdahl, the raising of an Egyptian obelisk and the transporting of massive building stones in Greece and Egypt were all successful experiments to demonstrate the feasibility of something. Nowadays we can go one step further and do some of the experimentation in the computer. In the film there is a striking computer reconstruction of the Parthenon showing the temple as it most probably looked shortly after it was completed. If further research indicated the addition, removal or alteration of a particular feature, the computer model could be easily updated.

The Parthenon

The Parthenon is one of the best-known architectural symbols of any civilization. Built in the 15-year period between 447-432 BCE this ancient Greek temple was designed as a replacement for a temple destroyed by the Persians in 480 BC. To build a temple of this size (101 x 228 ft.; 30.9m x 69.5m) in that short a timeframe was considered amazing but what was even more amazing was the quality of construction and finishing, which was superb. The leading politician of the day and the man behind the construction project was Pericles. According to Plutarch, the great Greek biographer writing centuries after the building was completed; one of the main reasons for the construction of the Parthenon and the other temples which surrounded it was the need to deal with growing unemployment. By embarking on a major public works program for the acropolis (the towering hill in Athens where the Parthenon and other temples dedicated to the gods were located) Pericles hoped to provide jobs for ordinary Athenians- carpenters, stonemasons, ivory-workers, painters, enamellers, pattern-makers, blacksmiths, rope-makers, weavers, engravers, merchants, coppersmiths, potters, shoemakers, tanners, laborers, etc.

At the same time and more importantly, he envisioned the Parthenon as an architectural masterpiece that would make a statement to the world about the superiority of Athenian values, their system of governance and their way of life. Because of this, only the best building materials were good enough- the finest stone, bronze, gold, ivory, ebony, cypress-wood- and the best artists and craftsmen. It was to be a building for the ages. In a funeral oration delivered in 430 BC Pericles expressed his pride in the city of Athens and there seems no doubt he was thinking of the Parthenon when he noted that “Mighty indeed are the marks and monuments we have left. Men of the future will wonder at us, as all men do today.”

The new construction project was not welcomed by everyone. There were some who were outraged that so much money was being spent on the construction “gilding and beautifying our city as if it were some vain woman decking herself out with costly stones and thousand talent temples”. Many were also upset that the monies to build the Parthenon were being supplied, reluctantly, by Athenian allies who had originally handed over this money for use in any future conflict against the Persians. Pericles argued that as long as the Athenians honored their commitment to defend these allies against Persian aggression, then the allies had nothing to complain about. And the majority of people supported Pericles. In fact his most vocal opponent was ostracized (banished for ten years) by a popular vote leaving the way clear to proceed with construction.

The Parthenon building program was carried out under the general direction of Pericles himself. He chose three men at the top of their professions to collaborate on the design and execution of the project. Although we don’t know everything that each did, it seems that Ictinuswas the chief architect, Callicratus acted as the project contractor and technical coordinator while Phideas was responsible for overseeing and integrating all artistic elements. He also personally created the enormous gold and ivory sculpture of the city goddess and produced some of the various sculptural groupings while supervising the production efforts of a small army of artists and craftsmen. Phideas was recognized at the time as being the greatest sculptor of his era but is acknowledged now as the greatest Greek sculptor of all time. The collaboration of the threesome was an enduring success.

There is no denying that the Parthenon construction project was expensive. (The cost, according to public accounts engraved in stone, was 469 silver talents. Attempts to translate that into a modern equivalent aren’t entirely satisfactory.) The main building material was Pentelic marble quarried from the flanks of Mt. Pentelikon, located about 10 mi/ 16 km from Athens. (The old Parthenon, the one destroyed by the Persians while it was partway through construction was the first temple to use this kind of marble.) The huge pieces of stone had to be hauled to the building site by oxcart. This structure was, by no means, the largest but what distinguishes the Parthenon from most other temples is the quality and extent of the sculptures. Many of the sculptures were made of the more expensive Parian marble, from the island of Paros, which most sculptors proclaimed the best kind of marble for their work. As a collection that shows Greek art at its zenith the Parthenon marbles (sculptures) are simply without peer.

The building itself is a work of art incorporating a number of aesthetic refinements calculated to make it appear as visually perfect as possible. Knowing that long horizontal lines appear to sag, even though they are absolutely straight, horizontal elements were deliberately curved and the vertical columns “fattened” in the middle to compensate for the vagaries of the human eye. This thickening in the middle made it look as though the columns were straining a bit under the weight of the roof, thus making the temple less static, more dynamic. Although the lines and distances in the Parthenon appear to be straight and equal, the geometry has been altered to achieve that illusion. It has been said about this building that “nothing is as it appears”.

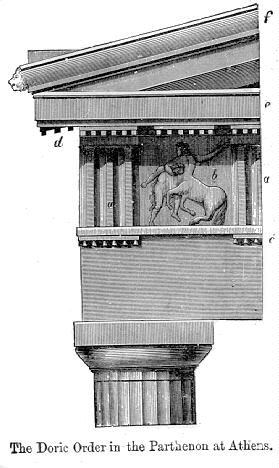

The Parthenon is a Doric temple, which artfully incorporated selected Ionic features to produce a building that many, including some of the world’s top architects, have called perfect. The Doric style uses thicker columns and has a more massive appearance (sometimes called masculine) than the Ionic (feminine) style. This may have been a politically inspired choice by Pericles, symbolically uniting Greeks of Dorian and Ionian backgrounds in one transcendent building.

The Parthenon is classified as a peripteral temple, that is, the perimeter of the structure is defined by columns, in this case by eight on the narrow ends and seventeen on the long sides, for a total of 46 columns. Sitting inside the exterior columns is a raised stone platform. This supports the floor-to-ceiling walls of a shoebox-like room called the Cella or Naos. In traditional temples this is a single room but in the case of the Parthenon, the Cella has been divided into two rooms. In the larger one, a huge standing statue of Athena was located, resting on a support slab. In front of the statute…a reflecting pool. In the smaller room, with the four interior columns, was kept the state treasury, including cash gifts to the deity. The collection of interior columns was necessary to support the roof that, like the rest of the building, was made of marble.

The portion of the Cella where the magnificent statue of Athena was kept was called the Hekatompedon (heka = 100) which was a hundred Athenian (Attic) feet in length, as the Greek room name indicates. The reflecting pool was filled with water to add humidity to the air and prevent splitting of the ivory elements of the huge chryselephantine (composite gold and ivory) statue. It is worth noting that the statue cost more than the building built to house it and the sculptor Phideas made it so that it’s gold panels could be removed, weighed and sold should the need arise. (That proved to be a wise decision because when he was later accused of pilfering some of the gold, he was able to quickly establish his innocence.)

None deny that the Parthenon building is a work of art in its own right but it was also embellished with a dazzling array of quality sculptures.

The Parthenon is one of the best known architectural symbols of any civilization. Built in the 15 year period between 447-432 BC this ancient Greek temple was designed as a replacement for a temple destroyed by the Persians in 480 BC. To build a temple of this size (101 x 228 ft.; 30.9m x 69.5m) in that short a timeframe was considered amazing but what was even more amazing was the quality of construction and finishing, which was superb. The leading politician of the day and the man behind the construction project was Pericles. According to Plutarch, the great Greek biographer writing centuries after the building was completed; one of the main reasons for the construction of the Parthenon and the other temples which surrounded it was the need to deal with growing unemployment. By embarking on a major public works program for the acropolis (the towering hill in Athens where the Parthenon and other temples dedicated to the gods were located) Pericles hoped to provide jobs for ordinary Athenians- carpenters, stonemasons, ivory-workers, painters, enamellers, pattern-makers, blacksmiths, rope-makers, weavers, engravers, merchants, coppersmiths, potters, shoemakers, tanners, laborers, etc.

At the same time and more importantly, he envisioned the Parthenon as an architectural masterpiece that would make a statement to the world about the superiority of Athenian values, their system of governance and their way of life. Because of this, only the best building materials were good enough- the finest stone, bronze, gold, ivory, ebony, cypress-wood- and the best artists and craftsmen. It was to be a building for the ages. In a funeral oration delivered in 430 BC Pericles expressed his pride in the city of Athens and there seems no doubt he was thinking of the Parthenon when he noted that “Mighty indeed are the marks and monuments we have left. Men of the future will wonder at us, as all men do today.”

The new construction project was not welcomed by everyone. There were some who were outraged that so much money was being spent on the construction “gilding and beautifying our city as if it were some vain woman decking herself out with costly stones and thousand talent temples”. Many were also upset that the monies to build the Parthenon were being supplied, reluctantly, by Athenian allies who had originally handed over this money for use in any future conflict against the Persians. Pericles argued that as long as the Athenians honored their commitment to defend these allies against Persian aggression, then the allies had nothing to complain about. And the majority of people supported Pericles. In fact his most vocal opponent was ostracized (banished for ten years) by a popular vote leaving the way clear to proceed with construction.

The Parthenon building program was carried out under the general direction of Pericles himself. He chose three men at the top of their professions to collaborate on the design and execution of the project. Although we don’t know everything that each did, it seems that Ictinuswas the chief architect, Callicratus acted as the project contractor and technical coordinator while Phideas was responsible for overseeing and integrating all artistic elements. He also personally created the enormous gold and ivory sculpture of the city goddess and produced some of the various sculptural groupings while supervising the production efforts of a small army of artists and craftsmen. Phideas was recognized at the time as being the greatest sculptor of his era but is acknowledged now as the greatest Greek sculptor of all time. The collaboration of the threesome was an enduring success.

There is no denying that the Parthenon construction project was expensive. (The cost, according to public accounts engraved in stone, was 469 silver talents. Attempts to translate that into a modern equivalent aren’t entirely satisfactory.) The main building material was Pentelic marble quarried from the flanks of Mt. Pentelikon, located about 10 mi/ 16 km from Athens. (The old Parthenon, the one destroyed by the Persians while it was partway through construction was the first temple to use this kind of marble.) The huge pieces of stone had to be hauled to the building site by oxcart. This structure was, by no means, the largest but what distinguishes the Parthenon from most other temples is the quality and extent of the sculptures. Many of the sculptures were made of the more expensive Parian marble, from the island of Paros, which most sculptors proclaimed the best kind of marble for their work. As a collection that shows Greek art at its zenith the Parthenon marbles (sculptures) are simply without peer.

The building itself is a work of art incorporating a number of aesthetic refinements calculated to make it appear as visually perfect as possible. Knowing that long horizontal lines appear to sag, even though they are absolutely straight, horizontal elements were deliberately curved and the vertical columns “fattened” in the middle to compensate for the vagaries of the human eye. This thickening in the middle made it look as though the columns were straining a bit under the weight of the roof, thus making the temple less static, more dynamic. Although the lines and distances in the Parthenon appear to be straight and equal, the geometry has been altered to achieve that illusion. It has been said about this building that “nothing is as it appears”.

The Parthenon is a Doric temple, which artfully incorporated selected Ionic features to produce a building that many, including some of the world’s top architects, have called perfect. The Doric style uses thicker columns and has a more massive appearance (sometimes called masculine) than the Ionic (feminine) style. This may have been a politically inspired choice by Pericles, symbolically uniting Greeks of Dorian and Ionian backgrounds in one transcendent building.

The Parthenon is classified as a peripteral temple, that is, the perimeter of the structure is defined by columns, in this case by eight on the narrow ends and seventeen on the long sides, for a total of 46 columns. Sitting inside the exterior columns is a raised stone platform. This supports the floor-to-ceiling walls of a shoebox-like room called the Cella or Naos. In traditional temples this is a single room but in the case of the Parthenon, the Cella has been divided into two rooms. In the larger one, a huge standing statue of Athena was located, resting on a support slab. In front of the statute…a reflecting pool. In the smaller room, with the four interior columns, was kept the state treasury, including cash gifts to the deity. The collection of interior columns was necessary to support the roof that, like the rest of the building, was made of marble.

The portion of the Cella where the magnificent statue of Athena was kept was called the Hekatompedon (heka = 100) which was a hundred Athenian (Attic) feet in length, as the Greek room name indicates. The reflecting pool was filled with water to add humidity to the air and prevent splitting of the ivory elements of the huge chryselephantine (composite gold and ivory) statue. It is worth noting that the statue cost more than the building built to house it and the sculptor Phideas made it so that it’s gold panels could be removed, weighed and sold should the need arise. (That proved to be a wise decision because when he was later accused of pilfering some of the gold, he was able to quickly establish his innocence.)

None deny that the Parthenon building is a work of art in its own right but it was also embellished with a dazzling array of quality sculptures.

The famous Parthenon frieze was a 160 meter (524 ft.) long mural, carved in high relief, a continuous band of sculpture. It encircled the Cella at the ceiling. It would have been very difficult to see and appreciate from the temple floor, the usual place from where it could be seen. The height of the frieze was just in excess of one meter (about 41” tall) and the depth of the relief was about the width of a dollar bill. (Phideas had the top portion of the frieze cut to that depth and the bottom portion incised somewhat less so as to make the scenes more apparent from the distant floor.) Despite the fact that it would have been difficult to discern details of the artwork from that viewpoint, especially given the dim, shadowy light of the temple, no less care was lavished on these images than on the other groupings. If only the gods could see and appreciate them, then that was sufficient.