Giovanni Battista Piranesi: Journeying through this 18th-century engraver-architect’s paper worlds.

By Dr. Susan Stewart

Avalon Foundation University Professor in the Humanities

Professor of English

Princeton University

This article, A Paper Archaeology: Piranesi’s Ruinous Fantasies, was originally published in The Public Domain Review under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0. If you wish to reuse it please see: https://publicdomainreview.org/legal/

Anomalies in the landscape of the present, ruins are the architectural equivalent of the syntactical anacoluthon, or non sequitur. They do not follow or precede — they call for the supplement of further reading, further syntax. These often massive and almost always empty material structures are both over- and underdetermined. They stand poised between the forms they were and the formlessness to which, in the absence of restoration, they are destined. They lose their original purposes and have the singularity of artworks, yet they are severed irremediably from their contexts of production. In the present they are fused, almost always destructively, with their immediate natural environments. They call for an active, moving viewer — often a traveler with a consciousness distinct from that of a local inhabitant — who can restore their missing coordinates and names. Their most well-known student, the eighteenth-century Venetian and Roman engraver-architect Giovanni Battista Piranesi, called them, in the dedication to his 1743 Prima parte di architetture, e prospettive, “queste parlanti ruine”: “these speaking ruins”.1

Born in 1720 in Mogliano Veneto, near Mestre, Piranesi was the son of a stone mason and throughout his life described himself as a “Venetian architect”. Piranesi’s fascination with stone and vaults, particularly on a “magnificent” scale, evolved from his family’s long interest in the origins of architecture in general and Roman monuments in particular.2 His brother Angelo, a Carthusian monk, provided him with lessons in Greek and Latin and a knowledge of ancient history, studies that fired him with zeal for classical antecedents. With his move to Rome in 1740 as a draftsman in the retinue of the Venetian Ambassador Francesco Venier, Piranesi could be found working in the bottega of Giuseppe Vasi by 1742, continuing to develop his skills as a printmaker, and exploring the archaeological sites at Herculaneum in 1743. When, out of funds, he returned to Venice, he frequented the studios of Tiepolo and the engraver Giuseppe Wagner and eventually, in 1747, returned to Rome as Wagner’s agent. In a period of less than a decade, he went on to publish his fantastic architectural images of the Prima parte, worked out plans for two drawing series, the grotteschi (grottos or grotesques) and the carceri d’invenzione (imaginary prisons), and began the production of his first set of Vedute di Roma.3 These early works by Piranesi already indicate the promise of what we might call a “paper architecture”: an evolving practice that eventually will bring together exacting details of first-hand observation and the farthest reaches of the draughtsman’s imagination. His “speaking” ruins — glimpses and vistas alike, broken open and inside out, vanishing and revealing at once — inspire his life-long pursuit of the reality of the past, his methods shaped by his over-arching commitments to speculation and artistic freedom.

In his preface to his four-volume work of 1756, Le Antichità Romane (Roman Antiquities), Piranesi explains that he plans to re-create Roman space on paper: “When I saw the remains of the ancient buildings of Rome lying as they do in cultivated fields or gardens and wasting away under the ravages of time, or being destroyed by greedy owners who sell them as materials for modern building, I determined to preserve them forever by means of engraving”.4 In the course of the development of his work, he displays a vertigo-inducing facility for moving between the page and the architectural space. The very title of La Tavola Monumentale (ca. 1749) from the grotteschi evokes a kind of trompe l’oeil, indicating the word for the engraving plate itself, la tavola, as well as what might be considered to be the monumental central image it presents — the tabula rasa facade of a stone block framed by an egg-and-dart border on which rest, or are hung, several cameos of figures in ancient drapery. The block is flanked to its left, at a recession, by another, similar, stone block. And yet it would be just as possible to believe we are looking at stone blocks of varying proximities, against each of which rests a picture frame. Or, perhaps more accurately, we could argue that it is only the title of the plate that gives the “tavola” its centrality within a veritable cascade of images. The work’s feathery curving lines obviously owe a debt to Piranesi’s exposure to Tiepolo, and especially the older Venetian’s 1743 capricci. Juxtaposed to the copperplates of the carceri with their harsh deep engraved lines effecting a resemblance to carved stone and hewn timbers, the copperplates of the grotteschi are marked with the lightest of etching strokes and nowhere more than in the frothy effects of La Tavola Monumentale.

What are we looking at when we look at La Tavola Monumentale? The first answer we might pose is “a sheet of paper”. That is, the print portrays on paper a sheet of paper, rippling at the bottom edge, scrolled slightly on the right side, where it rests on a textured surface, and vanishes on the left side as the border of the plate cuts it off. Perhaps only by imagining that we are looking at a drawing of a drawing — or, more accurately, an etching of a drawing — can we accommodate the jumble of objects we find here. We cannot be looking at a space informed by gravity, landscape, or any other order of experienced perception. Instead we see something like a dreamscape. In the upper left corner, barely visible, is a stone tablet inscribed with illegible and legible letters alike; those that are legible say che sieno / allegramente (roughly, “that are merrily”). A draped hand holds a carafe or glass beside it, and just below is a barrel, supposedly a wine barrel, on its side.5

To the right of these images are ambiguous billowing forms from which emerge shields (one of which bears the open-mouthed face of a Medusa) and escutcheons that seem lodged in clouds and braided through by garlands and feathers — all floating above a large urn fuming with smoke or steam. To the left of this cluster of plumes a trumpet is suspended over the great stone block. In the foreground a sphinxlike head protrudes from a vessel with vegetation sprouting from its edges; a petite, though monstrous, flying basilisk, or a sculpture of one, sits, wings spread, before the fuming urn; a welter of stones and sticks and logs and what could be pan pipes; a stick in the embrace of a slender snake, or the remains of a caduceus; what could be a tumbled model of an ancient arcade; skulls, and more.

The overabundance of particulars and the paucity of identifiable wholes here put the viewer-reader in a quandary. It is not simply that forms are ambiguous but rather that things and the atmosphere in which they reside are in transformation; they emerge, recede, change shape, scale, and dimension; foreground and background and horizon, perspective lines and point of view (e.g., are we looking up or looking down?) are indeterminate. We are inhabiting a paper world with its own internal dimensions of time and space.

It is therefore not surprising that the four grotteschi plates — this, La Tavola Monumentale; the skull-littered architectural extravaganza of Gli Scheletri (The Skeletons); the tumbling sarcophagi, tombs, and cascades of water, threaded with curling serpents, of La Tomba di Nerone (Nero’s Tomb); and the architectural debris, chains, bones, sphinx, reclining figures, and herm of L’Arco Trionfale (The Triumphal Arch) — have been variously interpreted as allegories.6 The temptation to allegorize presented by these prints underscores Piranesi’s unsurpassed skill in re-creating temporal sequence by means of works in series as well as the hermeneutic difficulties of “reading” the fragments and detritus of history. Both the carceri d’invenzione and the grotteschi are vital for understanding Piranesi’s relation to his “speaking ruins”. Uncommissioned works, determined so far as we can know solely by the expressive, intellectual, and technical needs of the artist, these early works set out a paradigm for printmaking that engages the connections between words, images, and their referents at every level — not the least of which is the fertility of reproduction.

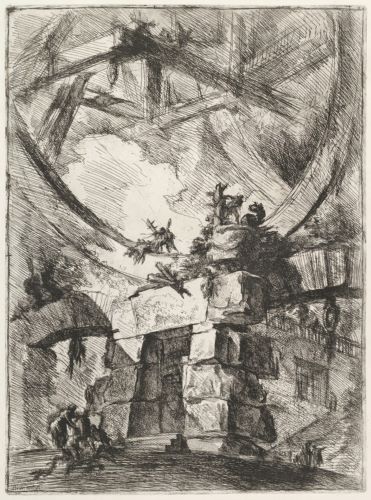

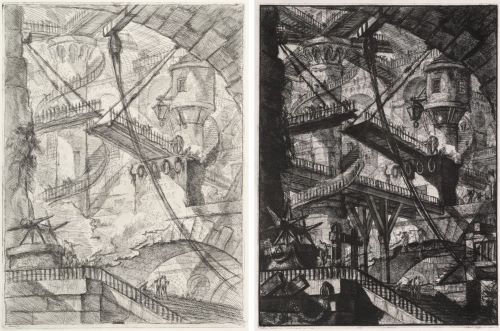

The vast machines of the well-known carceri, which seem designed to humiliate human powers of cognition and physical strength, are artifacts of a human hand; their enormous enclosed spaces the products of an even more enormous visionary mind. In the plate known as The Giant Wheel, numbered “IX” from the second edition onward, the cavernous architecture is intact, but the barely discernible figures — in torqued struggle along the rim, bowed in the foreground, or collecting in the distance — seem broken, nearly destroyed by some violence or suffering. A space above the wheel is evocative of sky, but is not sky — only adding to the feeling of claustrophobia and agoraphobia at once and so typical of the carceri as a group.

In contrast, the gathered cultural debris of the grotteschi — their broken statues, columns, tombs, roundels, reliefs, herms, cornucopias, shells, fasces, cameos, trumpets, bones, skulls, chains, mooring rings, and urns; their half-erased or faint inscriptions, rosettes, portraits, egg-and-dart moldings; their hazy skies, intimations of the sea, pines and palms, cascades, broken sticks and weeds, entwined with snakes and vines — is framed by illusionistic references, or metacommentaries, to the process of art itself. The image resolves, as it approaches the plate mark, to abstraction or a trompe l’oeil representation of the ground as paper. The lower right edge of La Tomba di Nerone shows a painter’s palette lying on what seems to be the ground. And we find, sticking up through a hole in a fallen enroulement, or scroll-shaped ornament, a set of paintbrushes.

Viewed in relation to one another, the carceri and grotteschi are a brilliant exercise in the representation of emptiness and fullness. The vast and looming carceri, their stairs and ladders leading to nowhere, continually drawing the eye upward to where glimpses of “life” and light might appear, as they do to the inhabitants of Plato’s cave, are defined by lack. We search in vain for exchange beyond pain, finding the inexorable fact of human limits within a silence that cries or screams would only echo and erase. The grotteschi are, by contrast, forests of symbols, dense with a kind of visual noise that demands the eye to keep searching particulars. The viewer is in the open — in this case, perhaps too free and confronted with an endless interpretive task. All of Piranesi’s early work manifests the tension between the closed actuality of material fact and the endlessly open possibilities tradition offers to invention. The ruin and disintegration of bodies and forms are transferred to the plate, but not simply to memorialize or capture them. Piranesi makes ruin the ground of a prolific reproduction.

The recent discovery that Piranesi used not only etching needles and several kinds of burins but also the more forceful cisello profilatori — a tool employed in metal sculpture — helps us understand the repertoire of lines he had at his disposal. Giovanna Scaloni writes that in the carceri Piranesi uses the burin (bulino) to bite into the metal with near “violence”, accentuating the deep volumes of the images, adding to their strong aura of three-dimensionality.7 Such a tool also requires gestures of stopping, lifting, and reinserting — quite the opposite of the flowing motion possible with the etching needle. The completely man-made world of the carceri, with their blocked, resolutely enclosed spaces, could not find a greater contrast to the fluid, organic motion created in the grotteschi via the etching needle. Mineral hardness and the soft vegetal imagery of vines, tendrils, and leaves are served respectively by the capacities of these tools.

With the grotteschi, Piranesi produced hybrid forms of ornament juxtaposed in an array without regard to single-point perspective. With his capricci, he brought disparate structures into a landscape that existed only within the borders of the plate.8 Perhaps because of his early fidelity to accuracy and the long tradition of printmaking as a medium for the measured representation of antique forms, Piranesi’s capricci take on a particularly fantastic aura. A set of drawn capricci from the mid-1750s from the collections of Robert Adam and his brother James show Piranesi assembling imaginary temples and tiered funerary monuments with small figures making their way up enormous flights of stairs. The assemblages spiral up into the clouds and evoke fantasies, if not of heaven, given the resolutely secular world of Piranesi’s imagination, then of flight, ascent, and drawing without limit.

As early as 1746–1748, Piranesi made a frontispiece for his Vedute di Roma that he called a Fantasy of Ruins with a Statue of Minerva in the Center Foreground. There real and imaginary ancient monuments are juxtaposed, rising from detritus in the foreground, amid foliage, clouds, and a ghostly architrave of spiraling columns in a fantasy landscape. The statue in the center is the Dea Roma, which we can find today, as Piranesi found it — standing in the courtyard of the Palazzo dei Conservatori on the Capitoline. A version of the right foot of the fragmentary statue of Constantine, elements of the Arco di Portogallo, a tomb topped in the Etruscan style by a reclining couple, and other “antique” remains appear with real and imaginary inscriptions. Lilliputian figures stand precariously on an arched bridge, reading an inscription taken from Pliny the Elder celebrating the conquests of Pompey.9

It may seem incongruous to find that Piranesi begins his presentation of his vedute, posited as actual spaces, accurately represented, with such fantastic images. Perhaps the minute figures reading within the miasma of images give us some clue that what follows will not be merely real. He experiments with a similar incongruity in his 1756 frontispiece to the second volume of Le Antichità Romane — a fantasia of the Via Appia packed with obelisks, urns, entablatures, and tombs, including his own imaginary tomb on the right and, below the she-wolf on the left, a tomb for the also living Robert Adam and his fellow Scotsman, the antiquarian Allan Ramsay. Nothing is factual in such an image except the context of the Via Appia and the inevitability of death, yet each element has been created and projected out of a deep knowledge of ancient remains. The fantasy is a kind of resurrection and tongue-in-cheek acknowledgment of mortality at once.

Appendix

Endnotes

- G. B. Piranesi, Prima parte di architetture, e prospettive (Rome: Stamperia de’ Fratelli Pagliarini, 1743).

- Piranesi’s maternal uncle Matteo Lucchesi served as chief architect for the “Magistrato alle acque”, the waterworks authority of the Venetian Republic, a position that would have involved supervising the construction and upkeep of breakwaters, moles, and massive foundations. In addition to his knowledge of aqueducts and other forms of civil engineering, Lucchesi was engaged with the formulation of theories regarding architectural history as he and his architect colleague Tommaso Temanza joined the intellectual circle around the Franciscan friar, intellectual, and architectural theorist Carlo Lodoli. Temanza and Lucchesi argued that all antique edifices were constructed according to a set of basic procedures as early builders employed blocks of stone and beams of timber. The first procedure used blocks of stones alone: the Egyptians relied on this technique and were followed by the Etruscans. The Greeks built their early structures in this “Egyptian manner” but introduced a second innovation as they created small timber houses with post-and-beam forms. Lucchesi and Temanza held that the Greeks went on to copy these timber forms using stone alone. However, since a stone architrave cannot span a large and high space, a further innovation was necessary. The Venetians described how one beam was replaced by two forming a gable, and then further supports were added. The Romans added an arch to Etruscan stone walls and Greek trabeation; their “mixed manner” made it possible to build enormous forms — baths, amphitheaters, and the Pantheon. Lucchesi and Temanza encouraged Piranesi to study architecture, and their valorization of Roman ingenuity would continue to inform his studies and endeavors — claims for Roman genius would lead him into a preoccupation with architectural polemics throughout his middle and late age. For the Greek “Egyptian manner” and Roman “mixed manner”, see Lola Kantor-Kazovsky, Piranesi as Interpreter of Roman Architecture and the Origins of His Intellectual World (Florence: Leo S. Olschki Editore, 2006), 177–78.

- Matthias Winner helpfully traces the history of the Italian term vedute and describes the valence between first-person observation of nature and imaginary projection that “views” involved in sixteenth-century sketching and painting practices in “Vedute in Flemish Landscape Drawings”. He shows the importance of the artist’s standpoint and practices of copying and transferring landscape images, including the work of Jan Brueghel the Elder, Jan Gossart, Maerten van Heemskerck, and other northern artists drawing in Rome. See Matthias Winner, “Vedute in Flemish Landscape Drawings of the 16th Century”, in Netherlandish Mannerism: Papers Given at a Symposium in Nationalmuseum Stockholm, September 21–22, 1984, ed. Görel Cavalli-Björkman (Stockholm: Nationalmuseum, 1985), 85–96.

- G. B. Piranesi, preface to Le Antichità Romane (Paris: Firmin Didot, Frères, 1835), n.p.

- The letters, according to an interpretation offered by Carlo Bertelli in 1976, represent a notation for the price of wine — “otto quattri foglietta a i che sieno allegramente” — otto is the number eight, a quattrino was a copper coin, a foglietta a half-liter measure. See Carlo Bertelli, “Le Parlanti Rovine”, in Grafica Grafica II, no. 2., ed. Carlo Bertelli (Rome: Calcografia Nazionale, 1976). See also Francesco Nevola, Giovanni Battista Piranesi: I Grotteschi; Gli anni giovanili 1720–1750 (Rome: Ugo Bozzi Editore, 2010), 207.

- The pathbreaking English-language Piranesi scholar John Wilton-Ely holds that Piranesi is likely to have executed the four plates as a contribution to the Accademia dell’Arcadia, the elite literary and artistic society that had its headquarters in the Bosco Parrasio on the Gianicolo. Wilton-Ely suggests that the newly elected Piranesi may have intended the plates to represent themes of renewal in concert with the Arcadian Academy’s ambitions to renew the culture. Maurizio Calvesi has claimed that Piranesi’s use of the noun grottesco and at times the adjective, as in grottesca invenzione and other applications of the notion, indicates not only the fantastic but also elements of the arabesque and the baroque and that such allusions are not merely decorative; they indicate the presence of meanings. Among these is the Roman origin of the term, in the decorative paintings found in the subterranean vaults (the grotte) of the Golden House of Nero in the late fifteenth century. Calvesi finds as well throughout Piranesi’s work a recurring set of allusions to the New Science of the Neapolitan philosopher of history Giambattista Vico, with the grotteschi particularly alluding to Vico’s interest in the Mosaic tablets of the law and the labors of Hercules. Calvesi believes that each of the grotteschi refers as well to one of the four seasons. More recently, Francesco Nevola has argued that whether or not the four grotteschi refer to Vico’s four eras in his spiral of history — that is, the era of the Giants, the era of the Egyptians, the era of the Romans, and the era of the Moderns — the series is about “the passage of time”. He goes on to give his own interpretation of the plates as a commentary on the ages of Gold, Silver, Bronze, and Heroes set out by Hesiod in his Works and Days. See John Wilton-Ely, “Design through Fantasy: Piranesi as Designer”, in Piranesi as Designer, ed. Sarah Lawrence and John Wilton-Ely (New York: Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, Smithsonian Institute, 2007), 18; Maurizio Calvesi, “Nota ai ‘grotteschi’ o capricci di Piranesi”, in Piranesi e la cultura antiquaria: Gli antecedenti e il contesto, ed. Anna Lo Bianco (Rome: Comune di Roma e Università degli Studi di Roma, 1983), 135–36; Calvesi, “Nota ai ‘grotteschi’”, 136–40. The Vico connection to Piranesi, which is based on the historical connection and correspondence Vico had with one of Piranesi’s Venetian mentors, the learned Franciscan friar Carlo Lodoli, is first laid out in Maurizio Calvesi’s introduction to the Italian edition of Henri Focillon’s pathbreaking study of the printmaker: Maurizio Calvesi, introduction to Giovanni Battista Piranesi, by Henri Focillon, ed. Maurizio Calvesi and Augusta Monferini (Bologna: Alfa, 1967), v–xlii; (see also Consoli, “Architecture and History”, 195–210; and Erika Naginski, “Preliminary Thoughts on Piranesi and Vico”, RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 53/54 (Spring–Autumn 2008): 152–67); and Nevola, Giovanni Battista Piranesi, 205.

- Giovanna Scaloni, “Carceri”, in Giambattista Piranesi, Matrici incise 1743–1753, ed. Ginevra Mariani (Rome: Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, Calcografia; Milan: Mazzotta, 2010), 52–53. Giovanna Scaloni is the technical and scientific coordinator of the Istituto Nazionale’s vast project to publish Piranesi’s matrice (plural of matrix, as introduced and described in chapter four of The Ruins Lesson), held in its vaults: there are now two volumes — those incised from 1743 to 1753, as cited at the beginning of this note, and those incised in 1756–1757: Giambattista Piranesi, Matrici incise 1756–1757, ed. Ginevra Mariani (Rome: Istituto Nazionale per la Grafica, Calcografia; Milan: Mazzotta, 2014). For discussion of the cisello profilatori, see Scaloni, “La tecnica incisoria nelle tavole delle Antichità Romane”, 54, in Giambattista Piranesi, Matrici incise 1756–1757. I extend my deepest thanks to Giovanna Scaloni and to Ginevra Mariani, the project’s director, for allowing me to see a number of the copperplates and first editions, and for sharing their knowledge, during my November 2016 visit to the Calcografia.

- As we have seen, this genre of imaginary topographies was practiced in painting by Piranesi’s mentor Tiepolo — in the 1740s and 1750s, Giovanni Paolo Panini had made capricci of Roman monuments. His amalgams of sites of ruins stand in contrast to his more careful, near ethnographic representation of contemporary scenes of Roman life in his own vedute. See David Mayernik, “The Capricci of Giovanni Paolo Panini”, in The Architectural Capriccio: Memory, Fantasy and Invention, ed. Lucien Steil (Farnham, UK: Ashgate, 2014), 33–41.

- Art in Rome in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Edgar Peters Bowron and Joseph J. Rishel (London: Merrell; Philadelphia: Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2000), 578–79, plate 422.

Public Domain Works

- Opere varie di architettura, prospettiva, groteschi, antichità, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1750)

- Grotteschi, Giovanni Battista Piranesi (c.1748)

- Carceri d’invenzione (Imaginary Prisons), Giovanni Battista Piranesi (1750/61)

Further Reading

- The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture, by Susan Stewart

- Piranesi Drawings: Visions of Antiquity, by Sarah Vowles

- Piranesi Unbound, by Carolyn Yerkes and Heather Hyde Minor