Approximately 21 people, including miners’ wives and children, were killed.

Curated/Reviewed by Matthew A. McIntosh

Public Historian

Brewminate

Introduction

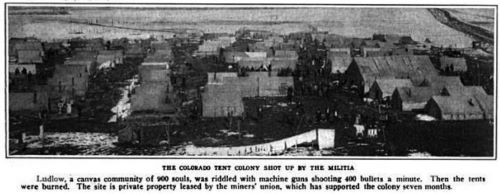

The Ludlow Massacre was a mass killing perpetrated by anti-striker militia during the Colorado Coalfield War. Soldiers from the Colorado National Guard and private guards employed by Colorado Fuel and Iron Company (CF&I) attacked a tent colony of roughly 1,200 striking coal miners and their families in Ludlow, Colorado, on April 20, 1914. Approximately 21 people, including miners’ wives and children, were killed. John D. Rockefeller Jr., a part-owner of CF&I who had recently appeared before a United States congressional hearing on the strikes, was widely blamed for having orchestrated the massacre.[6][7]

The massacre was the seminal event of the 1913–1914 Colorado Coalfield War, which began with a general United Mine Workers of America strike against poor labor conditions in CF&I’s southern Colorado coal mines.[8] The strike was organized by miners working for the Rocky Mountain Fuel Company and Victor-American Fuel Company. Ludlow was the deadliest single incident during the Colorado Coalfield War and spurred a ten-day period of heightened violence throughout Colorado. In retaliation for the massacre at Ludlow, bands of armed miners attacked dozens of anti-union establishments, destroying property and engaging in several skirmishes with the Colorado National Guard along a 225-mile (362 km) front from Trinidad to Louisville.[6] From the strike’s beginning in September 1913 to intervention by federal soldiers under President Woodrow Wilson’s orders on April 29, 1914, an estimated 69 to 199 people were killed during the strike. Historian Thomas G. Andrews has called it the “deadliest strike in the history of the United States.”[2]: 1

The Ludlow Massacre was a watershed moment in American labor relations. Socialist historian Howard Zinn described it as “the culminating act of perhaps the most violent struggle between corporate power and laboring men in American history”.[9] Congress responded to public outrage by directing the House Committee on Mines and Mining to investigate the events.[10] Its report, published in 1915, was influential in promoting child labor laws and an eight-hour work day. The Ludlow townsite and the adjacent location of the tent colony, 18 miles (29 km) northwest of Trinidad, Colorado, is now a ghost town. The massacre site is owned by the United Mine Workers of America, which erected a granite monument in memory of those who died that day.[11] The Ludlow tent colony site was designated a National Historic Landmark on January 16, 2009, and dedicated on June 28, 2009.[11] Subsequent investigations immediately following the massacre and modern archeological efforts largely support some of the strikers’ accounts of the event.[12]

Background

Areas of the Rocky Mountains have veins of coal close to the surface, providing significant and relatively accessible reserves. In 1867 these coal deposits caught the attention of William Jackson Palmer, then leading a survey team planning the route of the Kansas Pacific Railway.

At its peak in 1910, the coal mining industry of Colorado employed 15,864 people, 10% of jobs in the state.[2]: 96 Colorado’s coal industry was dominated by a handful of operators. Colorado Fuel and Iron was the largest coal operator in the west and one of the nation’s most powerful corporations, at one point employing 7,050 people and controlling 71,837 acres (290.71 km2) of coal land.[2]This article incorporates facts obtained from: Lawrence Kestenbaum, The Political Graveyard John D. Rockefeller purchased a controlling stake in the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company in 1902, and nine years later he turned over his controlling interest in the company to his son, John D. Rockefeller Jr., who managed the company from his offices at 26 Broadway in New York.[13]

Mining was dangerous and difficult work. Colliers in Colorado were constantly threatened by explosions, suffocation, and collapsing mine walls. In 1912 the death rate in Colorado’s mines was 7.055 per 1,000 employees, compared to a national rate of 3.15.[2]: 18 In 1914 the United States House Committee on Mines and Mining reported:

Colorado has good mining laws and such that ought to afford protection to the miners as to safety in the mine if they were enforced, yet in this State the percentage of fatalities is larger than any other, showing there is undoubtedly something wrong in reference to the management of its coal mines.[14]: 19

Miners were generally paid according to tonnage of coal produced, while so-called “dead work”, such as shoring up unstable roofs, was often unpaid.[14]: 19 The tonnage system drove many poor and ambitious colliers to gamble with their lives by neglecting precautions and taking on risk, with consequences that were often fatal.[2]: 138–139 Between 1884 and 1912 mining accidents claimed the lives of more than 1,700 in Colorado.[15] In 1913 alone 110 men died in mine-related accidents.[2]: 236–237

Colliers had little opportunity to air their grievances. Many resided in company towns, in which all land, real estate, and amenities were owned by the mine operator, and which were expressly designed to inculcate loyalty and squelch dissent.[2]: 197 Welfare capitalists believed that anger and unrest among the workers could be placated by raising colliers’ standard of living, while subsuming it under company management. Company towns indeed brought tangible improvements to many colliers’ lives, including larger houses, better medical care, and broader access to education.[2]: 199 But owning the towns gave companies considerable control over all aspects of workers’ lives, and they did not always use this power to augment public welfare. Historian Philip S. Foner has described company towns as “feudal domain[s], with the company acting as lord and master. … The ‘law’ consisted of the company rules. Curfews were imposed. Company guards—brutal thugs armed with machine guns and rifles loaded with soft-point bullets—would not admit any ‘suspicious’ stranger into the camp and would not permit any miner to leave.” Miners who came into conflict with the company were often summarily evicted from their homes.[16]

Frustrated by working conditions they found unsafe and unjust, colliers increasingly turned to unionism. Nationwide, organized mines boasted 40% fewer fatalities than nonunion mines.[14]: 19 Colorado miners repeatedly attempted to unionize after the state’s first strike in 1883. The Western Federation of Miners organized primarily hard-rock miners in the gold and silver camps during the 1890s.

Beginning in 1900, the United Mine Workers of America began organizing coal miners in the western states, including southern Colorado. The union decided to focus on the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company because of its harsh management tactics under the conservative and distant Rockefellers and other investors. To break or prevent strikes, the coal companies hired strike breakers, mainly from Mexico and southern and eastern Europe.

Strike

Despite attempts to suppress union activity, the United Mine Workers of America secretly continued its unionization efforts in the years leading up to 1913. Eventually, the union presented a list of seven demands:

- Recognition of the union as bargaining agent

- Compensation for digging coal at a ton rate based on 2,000 pounds[17] (previous ton rates were of long tons of 2,200 pounds)

- Enforcement of the eight-hour work-day law

- Payment for “dead work” (laying track, timbering, handling impurities, etc.)

- Weight checkmen elected by the workers (to keep company weightmen honest)

- Right to use any store, and to choose their boarding houses and doctors

- Strict enforcement of Colorado’s laws (such as mine safety rules, abolition of scrip), and an end to the company guard system

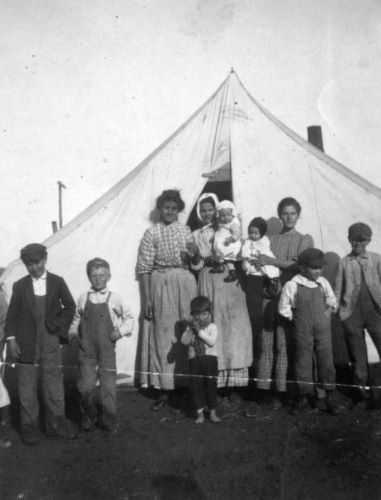

The major coal companies rejected the demands. In September 1913 the United Mine Workers of America called a strike.[18] Those who went on strike were evicted from their company homes and moved to tent villages prepared by the union. The tents were built on wood platforms and furnished with cast-iron stoves on land the union had leased in preparation for a strike.

When leasing the sites, the union had selected locations near the mouths of canyons that led to the coal camps in order to block any strikebreakers’ traffic.[17]

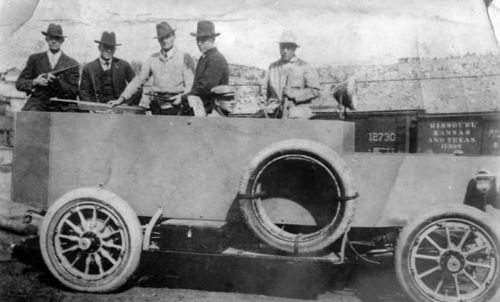

Baldwin–Felts had a reputation for aggressive strike breaking. Agents shone searchlights on the tent villages at night and fired bullets into the tents at random, occasionally killing and maiming people. They used an improvised armored car, mounted with a machine gun the union called the “Death Special”, to patrol the camp’s perimeters. The steel-covered car was built at the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company plant in Pueblo, Colorado, from the chassis of a large touring sedan. Confrontations between striking miners and working miners, whom the union called scabs, sometimes resulted in deaths. Frequent sniper attacks on the tent colonies drove the miners to dig pits beneath the tents to hide in. Armed battles also occurred between (mostly Greek) strikers and sheriffs recently deputized to suppress the strike: this was the Colorado Coalfield War.[19]

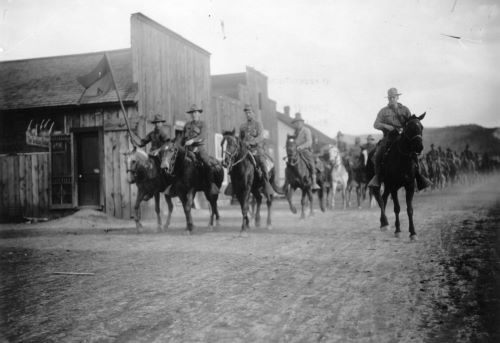

As strike-related violence mounted, Colorado governor Elias M. Ammons called in the Colorado National Guard on October 28. At first, the Guard’s appearance calmed the situation, but the Guard leaders’ sympathies lay with company management. Guard Adjutant-General John Chase, who had served during the violent Cripple Creek strike 10 years earlier, imposed a harsh regime. On March 10, 1914, a replacement worker’s body was found on the railroad tracks near Forbes, Colorado. The National Guard said the strikers had murdered the man.[20] In retaliation, Chase ordered the Forbes tent colony destroyed. The attack was launched while the residents were attending a funeral of two infants who had died a few days earlier. Photographer Lou Dold witnessed the attack, and his images of the destruction often appear in accounts of the strike.[20]

The strikers persevered until the spring of 1914. By then, according to historian Anthony DeStefanis, the National Guard had largely broken the strike by helping the mine operators bring in non-union workers. The state had also run out of money to maintain the Guard, and Ammons decided to recall them. He and the mining companies, fearing a breakdown in order, left one company of Guardsmen in southern Colorado. They formed a new company called “Troop A”, which consisted largely of Colorado Fuel & Iron Company mine camp guards and mine guards hired by Baldwin–Felts, who were given National Guard uniforms.[20]

Massacre

On the morning of April 20, the day after some in the tent colony celebrated Orthodox Easter, three Guardsmen appeared at the camp ordering the release of a man they claimed was being held against his will. The camp leader, Louis Tikas, left to meet with Major Patrick J. Hamrock at the train station in Ludlow village, 1⁄2 mile (800 m) from the colony. While this meeting was progressing, two militias installed a machine gun on a ridge near the camp and took positions along a rail route about half a mile south of Ludlow. Simultaneously, armed Greek miners began flanking to an arroyo. When two of the militias’ dynamite explosions–detonated to draw support from the National Guard units at Berwind and Cedar Hill–alerted the Ludlow tent colony, the miners took up positions at the bottom of the hill. When the militia opened fire, hundreds of miners and their families ran for cover.[21]

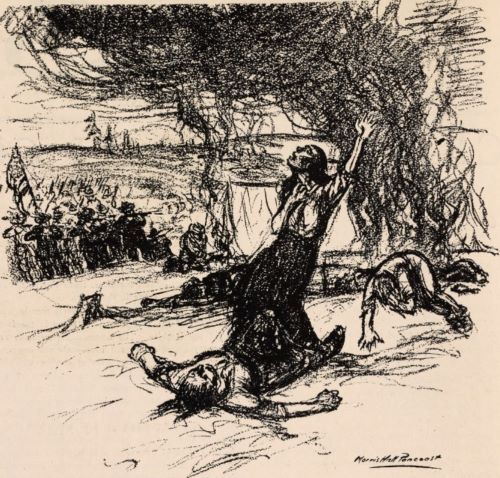

The fighting raged for the entire day. The militia was reinforced by non-uniformed mine guards later in the afternoon. At dusk a passing freight train stopped on the tracks in front of the Guards’ machine-gun placements, allowing many of the miners and their families to escape to an outcrop of hills to the east called the Black Hills. By 7 p.m., the camp was in flames, and the militia descended on it and began to search and loot it. Tikas had remained in the camp the entire day and was still there when the fire started. He and two other men were captured by the militia. Tikas and Lt. Karl Linderfelt, commander of one of two Guard companies, had confronted each other several times in the previous months. While two militiamen held Tikas, Linderfelt broke a rifle butt over his head. Tikas and the other two captured miners were later found shot dead. Tikas had been shot in the back.[2]: 272 [22] Their bodies lay along the Colorado and Southern Railway tracks for three days in full view of passing trains.[23] The militia officers refused to allow them to be moved until a local of a railway union demanded they be taken away for burial.

During the battle, four women and 11 children hid in a pit beneath one tent, where they were trapped when the tent above them was set on fire. Two of the women and all the children suffocated. These deaths became a rallying cry for the United Mine Workers of America, who called the incident the Ludlow Massacre.[24]

Julia May Courtney reported different numbers in her contemporaneous article “Remember Ludlow!” for the magazine Mother Earth. She said that, in addition to men who were killed, a total of 55 women and children had died in the massacre. According to her account, the militia:

fired the two largest buildings—the strikers’ stores—and going from tent to tent, poured oil on the flimsy structures, setting fire to them. From the blazing tents rushed the women and children, only to be beaten back into the fire by the rain of bullets from the militia. The men rushed to the assistance of their families; and as they did so, they were dropped as the whirring messengers of death sped surely to the mark … into the cellars—the pits of hell under their blazing tents—crept the women and children, less fearful of the smoke and flames than of the nameless horror of the spitting bullets. One man counted the bodies of nine little children, taken from one ashy pit, their tiny fingers burned away as they held to the edge in their struggle to escape … thugs in State uniform hacked at the lifeless forms, in some instances nearly cutting off heads and limbs to show their contempt for the strikers. Fifty-five women and children perished in the fire of the Ludlow tent colony. Relief parties carrying the Red Cross flag were driven back by the gunmen, and for twenty-four hours the bodies lay crisping in the ashes, while rescuers vainly tried to cross the firing line.[25][26]

Some reports say a second machine gun was brought in to support the estimated 200 Guardsmen who participated in the engagement, and that a Colorado and Southern train’s operators purposely put their engine between a machine gun and the strikers as a shield against National Guard fire.[4][27]

A board of Colorado military officers described the events as beginning with the killing of Tikas and other strikers in custody, with gunfire largely emanating from the southwestern corner of the Ludlow Colony. Guardsmen stationed on “Water Tank Hill”—the name for the machine gun position—fired into the camp. The Guardsmen reported having seen women and children withdrawing the morning before the battle and said they thought the strikers would not have begun firing if they had women still with them. The board’s official report commended the “truly heroic behavior” of Linderfelt, the guardsmen, and the militia during the battle and blamed the strikers for any civilian casualties during the engagement,[28] despite those killed being family members of the strikers.[29] The report also blamed the looting that occurred afterward on “Troop ‘A'”, a unit composed largely of non-uniformed mine guards who had been integrated into the Guard.

In addition to the miners and their family members, three regular members of the National Guard and one other militiaman were reported killed in the day’s fighting by contemporary accounts.[29][30] However, modern historians assert that only one of the militia’s number, a private named Martin of the National Guard, was killed. Martin was fatally shot in the neck, presumably by strikers.[2]: 2

Aftermath

In the aftermath of the massacre came the Ten Day War, part of the wider Colorado Coalfield War.[31] As news of the deaths of women and children spread, the leaders of organized labor issued a call to arms. They urged union members to get “all the arms and ammunition legally available”. Subsequently, the coal miners began a large-scale guerrilla war against the mine guards and facilities throughout Colorado’s southern coalfields. In the town of Trinidad, the United Mine Workers of America openly and officially distributed arms and ammunition to strikers at union headquarters.[32] Over the next ten days, 700 to 1,000 strikers “attacked mine after mine, driving off or killing the guards and setting fire to the buildings.” At least 50 people, including those at Ludlow, were killed during the ten days of fighting between the guards and miners. Hundreds of state militia reinforcements were rushed to the coalfields to regain control of the situation.[32] The fighting ended only after President Woodrow Wilson sent in federal troops.[33] The Colorado Coalfield War produced a total death toll of approximately 75.[34]

The United Mine Workers of America finally ran out of money, and called off the strike on December 10, 1914.[34] In the end, the strikers’ demands were not met, the union did not obtain recognition, and many striking workers were replaced.[35] 408 strikers were arrested, 332 of whom were indicted for murder.[36]

Of those present at Ludlow during the massacre, only John R. Lawson, leader of the strike, was convicted of murder, and the Colorado Supreme Court eventually overturned the conviction.[34] Twenty-two National Guardsmen, including 10 officers, were court-martialed.[36] While Linderfelt was found responsible for the deaths of Tikas and other strikers that exhibited execution-style injuries, he and all others were acquitted.[37]

An Episcopalian minister, Reverend John O. Ferris, pastored Trinity Church in Trinidad and another church in Aguilar. He was one of the few pastors in Trinidad permitted to search and provide Christian burials to the deceased victims of the Ludlow Massacre.[38]

Legacy

The massacre sparked nationwide reproach for the Rockefellers, especially in New York, where protesters demonstrated outside of the Rockefeller building in New York City. Protesters led by Ferrer Center anarchists Alexander Berkman and Carlo Tresca followed when Rockefeller Jr. fled 30 miles (48 km) upstate to the family estate near Tarrytown. In early July, a failed bomb plot on the Tarrytown estate ended with a dynamite explosion in East Harlem and three dead anarchists. The New York City Police Department inaugurated its bomb squad within a month. Bomb plots continued throughout the rest of the year.[41]

Although the UMWA failed to win recognition from the company, the strike had a lasting effect both on conditions at the Colorado mines and on labor relations nationally. John D. Rockefeller Jr. engaged W. L. Mackenzie King, a labor relations expert and future Canadian Prime Minister, to help him develop reforms for the mines and towns. Improvements included paved roads and recreational facilities, as well as worker representation on committees dealing with working conditions, safety, health, and recreation.

Rockefeller Jr. also brought in pioneer public relations expert Ivy Lee, who warned that the Rockefellers were losing public support and developed a strategy that Rockefeller followed to repair it. Rockefeller had to overcome his shyness, go to Colorado to meet the miners and their families, inspect the homes and the factories, attend social events, and listen closely to the grievances. This was novel advice, and attracted widespread media attention. The Rockefellers were able both to resolve the conflict, and present a more humanized versions of their leaders.[42]

Over time, Ludlow has assumed “a striking centrality in the interpretation of the nation’s history developed by several of the most important left-leaning thinkers of the 20th century.”[2]: 6 Historian Howard Zinn, noted for his controversial reframing of U.S. history, wrote his master’s thesis and several book chapters on Ludlow.[43][44][45] George McGovern wrote his doctoral dissertation on the subject.

A United States Commission on Industrial Relations (CIR), headed by labor lawyer Frank Walsh, conducted hearings in Washington, DC, collecting information and taking testimony from all the principals, including Rockefeller, Sr., who testified that, even after knowing that guards in his pay had committed atrocities against the strikers, he “would have taken no action” to prevent his hirelings from attacking them.[46]

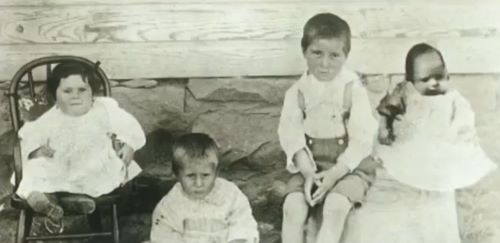

The last survivor of the Ludlow Massacre, Ermenia “Marie” Padilla Daley, was 3 months old during the event. Her father was a miner and she was born in the camp. Her mother took her and her siblings away as violence escalated; they traveled by train to Trinidad, Colorado. The evacuation resulted in the family having to split up afterward. Daley was cared for by various families and also placed for a time in orphanages in Pueblo and Denver. She worked as a housekeeper, then married a consultant whose work allowed them to travel the world.[47] Daley died on March 14, 2019, at age 105.[48]

Endnotes

- Simmons, R. Laurie; Simmons, Thomas H.; Haecker, Charles; Siebert, Erika Martin (May 2008). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 41, 45.

- Andrews, Thomas G. (2010). Killing for Coal. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Walker, Mark (2003). “The Ludlow Massacre: Class, Warfare, and Historical Memory in Southern Colorado”. Historical Archaeology. New York City: Springer. 37 (3): 66–80.

- McGuire, Randall (November–December 2004). “Letter from Ludlow: Colorado Coalfield Massacre: Excavators uncover chilling evidence of a brutal assault during a 1914 miners’ strike”. Archaeology. 57 (6).

- Simmons, R. Laurie; Simmons, Thomas H.; Haecker, Charles; Martin Siebert, Erika (May 2008). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 41, 45.

- “Ludlow Massacre”, Denver University

- R. Laurie Simmons; Thomas H. Simmons; Charles Haecker; Erika Martin Siebert (May 2008). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 41, 45.

- “The Invention of Public Relations”. YouTube.

- Zinn, Howard (1970). The politics of history. Boston, Massachusetts: Beacon Press. p. 79.

- United States Commission on Industrial Relations (1915). Final Report and Testimony Submitted to Congress by the Commission of Industrial Relations, The Colorado Miners’ Strike. Government Printing Office. pp. 6345–8948.

- McPhee, Mike (June 28, 2009). “Mining Strike Site in Ludlow Gets Feds’ Nod”. Denver Post. Denver.

- Simmons, R. Laurie; Simmons, Thomas H.; Haecker, Charles; Siebert, Erika Martin (May 2008). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony (PDF). National Park Service.

- Zinn 1990, p. 81.

- Martelle, Scott (2007). Blood Passion: The Ludlow Massacre and Class War in the American West. Rutgers University Press.

- Campbell, Ballard (2008). Disasters, Accidents, and Crises in American History: A reference guide to the nation’s most catastrophic events. p. 221.

- Foner 1990, p. 198.

- Lowry, Sam. “1914: The Ludlow massacre” (PDF). Libcom.org. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Zinn, Howard (1997). The Zinn Reader. Seven Stories Press. p. 187.

- DeStefanis, Anthony R. (September 2012). “The Road to Ludlow: Breaking the 1913–14 Southern Colorado Coal Strike”. Journal of the Historical Society. Springfield, Illinois: University of Illinois Springfield. 12 (2): 341–390.

- DeStefanis, “The Road to Ludlow.”

- Simmons, R. Laurie; Simmons, Thomas H.; Haecker, Charles; Siebert, Erika Martin (May 2008). National Historic Landmark Nomination: Ludlow Tent Colony (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 41–42.

- Fink, Walter H. (1914). The Ludlow Massacre. Denver: Williamson-Haffner.

- Fink, Walter H. (1914). The Ludlow Massacre. Denver: Williamson-Haffner. p. 16.

- Zinn, Howard. “The Ludlow Massacre”. A People’s History of the United States. pp. 346–349.

- Zinn, Howard; Arnove, Anthony (2004). Voices of a People’s History of the United States. Seven Stories Press. pp. 280–282.

- Julia, Courtney (May 1914). “Remember Ludow!”. Mother Earth: 73.

- Sunseri, Alvin (1972). The Ludlow Massacre: A study in the mis-employment of the National Guard (Report). University of Northern Iowa.

- Edward J. Boughton (May 2, 1914). Ludlow, Being the report of the special board of officers appointed by the governor of Colorado to investigate and determine the facts with reference to the armed conflict between the Colorado National Guard and certain persons engaged in the coal mining strike at Ludlow, Colo., April 20, 1914 (Report). Denver: Williamson-Haffner Co.

- Dehler, Gregory. “Ludlow Massacre”. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Fink, Walter H. (1914). The Ludlow Massacre. Denver, Colorado: United Mine Workers Association District 15. p. 25. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- Newton-Matza, Mitchell (March 26, 2014). Disasters and Tragic Events: An Encyclopedia of Catastrophes in American History [2 volumes]. ABC-CLIO. p. 223.

- Norwood, Stephen H. (April 3, 2003). Strikebreaking and Intimidation: Mercenaries and Masculinity in Twentieth-Century America. Univ of North Carolina Press. p. 148.

- Danver, Steven Laurence (2011). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 710.

- Johnson, Marilynn S. (June 5, 2014). Violence in the West: The Johnson County Range War and the Ludlow Massacre—A Brief History with Documents. Waveland Press. p. 28.

- Zinn, Howard; Frank, Dana; Kelley, Robin D. G. (2002). Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century. Beacon Press. p. 53.

- Weir, Robert E. (2013). Workers in America: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 153.

- Zinn, Howard; Frank, Dana; Kelley, Robin D. G. (2002). Three Strikes: Miners, Musicians, Salesgirls, and the Fighting Spirit of Labor’s Last Century. Beacon Press. p. 52.

- yongli (September 21, 2016). “Rev. John O. Ferris”. coloradoencyclopedia.org. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- “Children of Ludlow”. C-SPAN. July 11, 2016. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- “Cheyenne Record May 7, 1914 — Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection”. www.coloradohistoricnewspapers.org. Retrieved November 17, 2018.

- Wallace, Mike (2017). Greater Gotham: A History of New York City from 1898 to 1919. Oxford University Press. p. 1036.

- Robert L. Heath, ed.. Encyclopedia of Public Relations (2005) 1:485

- Plotnikoff, David (December 20, 2012). “Zinn’s influential history textbook has problems, says Stanford education expert”. Stanford Report. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- Wilentz, Sean (February 1, 2010). “An experts’ history of Howard Zinn”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- 1=Beneke, Chris; Stephens, Randall (July 24, 2012). “Lies the Debunkers Told Me: How Bad History Books Win Us Over Historian, United States Senator and Democratic presidential nominee”. The Atlantic. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- Beverly Gage, The Day Wall Street Exploded, Oxford University Press, 2009, p. 94.

- Kesting, Amanda (January 12, 2018). “One of the last living survivors of the Ludlow Massacre celebrates 104th birthday”. Retrieved April 20, 2021.

- “E. Marie Daley Obituary”. Dignity Memorial. United States: SCI Shared Resources, LLC. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

Originally published by Wikipedia, 06.19.2003, under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported license.